Tradition! Tradition!

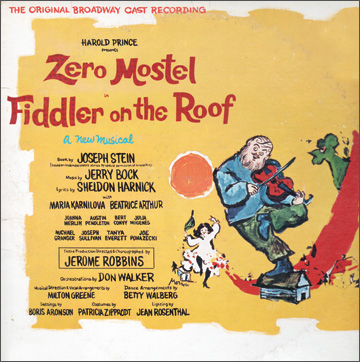

Judged by the sublimity of its songs or the freshness of its form, Fiddler on the Roof hardly merits inclusion on the short list of the greatest Broadway musicals. Unlike the creators of Show Boat, Oklahoma!, or West Side Story composer Jerry Bock, lyricist Sheldon Harnick, and playwright Joseph Stein did not reimagine the possibilities of the genre. A Chorus Line enjoyed an even longer Broadway run, My Fair Lady is more enchanting, and several other musicals have more and bigger hit songs. But has any musical ever exceeded the expectations of its creators more spectacularly than did Fiddler on the Roof?

Opening in September 1964, Fiddler was supposed to do little more than satisfy Jewish nostalgia. Instead, it managed to become a wonder of wonders, insinuating itself into the hearts of millions of playgoers around the globe. More than a theatrical production, Fiddler became a phenomenon, and when the Hollywood version appeared in 1971, interest in the fate of Anatevka seemed practically universal. Sometimes, apparently, it takes a village to make a global village.

How this process occurred, from inspiration to impact, is the subject of Alisa Solomon’s terrific book. Though subtitled “a cultural history,” it is more than that. For it is also a work of social history, and it provides a riveting account of how an adaptation from a Yiddish storyteller came close—against all odds—to achieving universal appeal. Fiddler thus defied the suspicion that staging Eastern European Jewry would be too parochial to sell tickets to the multitudes that popular entertainment covets.

Based on research in four dozen archives, as well as extensive interviews and a copious published literature, Wonder of Wonders may be the best volume ever written about an American musical. Solomon writes in a sprightly prose that neither condescends nor gushes, and she has generally done her own translations from the Yiddish. Little needs to be added (or corrected) to the author’s painstaking yet thrilling effort to trace how half a century of convulsive Jewish history was needed before the haunting power of roughly half a dozen tales of Sholem-Aleichem could make it to Broadway. There, Fiddler broke a box-office record (later eclipsed), before playing to packed houses from Tel Aviv to Tokyo, from Buenos Aires to Berlin and even Ankara. The popularity of what Solomon calls a “middlebrow commercial entertainment” almost seemed to render the historic tension between the universal and the particular moot.

Fiddler has remained a staple of American Jewish culture. On Friday evenings in Jewish summer camps, “Sabbath Prayer” is commonly sung as the candles are lit, and when playing at Jewish weddings, few bands dare to skip “Sunrise, Sunset,” at which the assembled guests almost invariably weep while vaguely imagining that the tune actually comes from Anatevka rather than Tin Pan Alley.

How can such unanticipated success be accounted for? Triumphs in popular entertainment are often mysterious. Enterprises with no ambition larger than the desire to momentarily attract audiences sometimes persevere as an enduring source of delight. During tryouts in Detroit, the creators of Fiddler were gripped with the white-knuckle fear that no one would fill the seats once the Hadassah benefit parties evaporated. Yet Fiddler somehow managed to satisfy needs and to tap yearnings that those responsible for it did not realize were there. In the succeeding decades, tastes would shift, and Broadway would cease to be central to the nation’s musical culture. And yet somehow this show has not faded from popular consciousness or collective memory, which is another way of saying that (miracle of miracles) Fiddler on the Roof has actually transcended a genre that now survives on the margins of American culture, often depending on the life support of revivals. Already four revivals of Fiddler have been mounted on Broadway, Solomon notes. The most recent (featuring Alfred Molina and then Harvey Fierstein as Tevye) lasted for nearly two years, and its 781 performances easily set yet another box-office record for revivals.

No small part of Solomon’s explanation for such impact and durability is—no other word will do—genius. It was Jerome Robbins, the director and choreographer, who realized how decisively the show was about “tradition”—how to honor it and how to adapt it. It was he who represented most poignantly the ambivalence that Jews such as him felt toward the obligations of tradition. Though he shared his family name of Rabinowitz with the author who had adopted the cheerful pen name of Sholem-Aleichem, the ballet choreographer turned Broadway director had long deemed Jewishness more a burden than a blessing and had sought throughout much of his career to wriggle out from the claims of peoplehood and of Jewish destiny. Wonder of Wonders depicts the interior struggle that Robbins—tortured, indecisive, ferocious—waged in facing an artistic challenge that could not be isolated from the elusive meaning of ancestral loyalties. No one in the production, or indeed on Broadway, was more afflicted with psychic demons (or inflicted more tzuris upon his collaborators) than Jerome Robbins.

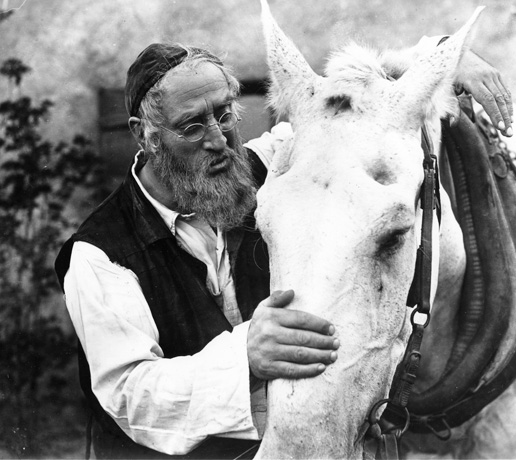

Part of the difficulty came from his insistence upon casting Zero Mostel, a 230-pound dynamo, as Tevye. In 1953 Robbins had named names before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which subpoenaed Mostel two years later. Zero, who invoked the Fifth Amendment, was blacklisted. The actor therefore switched to painting before triumphing off-Broadway and then on it. The son of an Orthodox rabbi, Mostel never let Robbins forget which one of them was more deeply immersed in the rich Eastern European Jewish culture to which the play paid tribute. But Robbins was evidently a quick study. After the curtain came down on opening night, his father wept as he hugged him, and asked, “How did you know all that?”

Mostel did deliver one of the memorable, must-see performances in a postwar musical, as iconic as that of Ethel Merman in Annie Get Your Gun or Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl, but Solomon rightly notes that Fiddler clicked with audiences even after he had left the cast. Something was happening in early 1960s America, and neither the charm of the performers nor the claims of nostalgia can fully account for the excitement that Fiddler stirred when it opened. The multicultural moment had not yet arrived, but public space could suddenly be carved out for Yiddishkeit (or at least vestiges of it) to be expressed without anxiety.

The 1960s began with Jack Lemmon announcing near the end of The Apartment that “I’ve decided to become a mentsch,” but so unsure were co-scenarists Billy Wilder and Izzy Diamond of their audience’s Yiddish comprehension that Lemmon was obliged to define that noun (“a human being”). Mark Cohen’s recent biography of comedian Allan Sherman shows just how suddenly Jewish in-jokes and allusions went mainstream: In 1962 and 1963 all three of his LPs about “my son, the” (fill in the blank) went gold. The decade ended in 1969 with the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint, a best-seller with more than a few Yiddish words besides mentsch. Such a shift in the tectonic plates of American culture could not have been predicted. The astonishing success of Fiddler on the Roof can certainly be attributed to its distinctive dramatic and musical virtues, but the emergence of unabashed Jewish ethnicity in the early 1960s undoubtedly gave a musical about the Old Country a welcome boost.

In 1939 the Forverts found Maurice Schwartz’s film Tevye der Milkhiker to be a betrayal, and condemned the film because “merely a shadow of Sholem-Aleichem has remained.” Joseph Stein wanted the vocabulary of Fiddler to be 99 percent English, so it was hardly surprising that when the play opened, Irving Howe found it “disheartening” and “a tasteless jumble,” and famously ridiculed Anatevka as “the cutest shtetl we never had.” This was at least a little unfair. After all, Act I ends with a pogrom, and Act II ends with the eviction of the town’s Jews. For her part, Alisa Solomon is wryly appreciative of what Fiddler has wrought. It has become, she writes, “a global touchstone for an astonishing range of concerns: Jewish identity, American immigrant narratives, generational conflict, communal cohesion, ethnic authenticity.” Half a century ago the popularity of Fiddler seemed to prove that America had fully accepted Jewishness. Since then, Fiddler has become a cultural touchstone of Jewishness itself. Now that highbrow resistance to this exuberant and tender musical has faded, it has simply become irresistible.

Suggested Reading

Mysterious Mishnah

According to a midrash, God will tell the contending nations: “He who possesses my mystery—he is my son.” And when they ask “What is your mystery?” God will reply, “It is the Mishnah.” How do you translate a mystery?

Richard Wolin on Arendt’s “Banality of Evil” Thesis

Seyla Benhabib responds to Richard Wolin's critique of her review of Bettina Stangneth's Eichmann Before Jerusalem.

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

It Was Like This: Excerpts from an Academic Memoir

Scenes from Anita Shapira’s gripping memoir.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In