Rallying Round the Flags

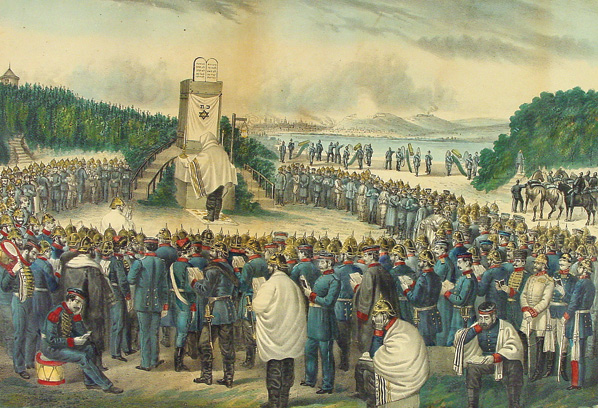

“Never before in history,” Derek Penslar observes, “had so many Jews been mobilized for battle” as in World War I. There were “over one million in the Allied forces and some 450,000 among the armies of the Central Powers.”

Inevitably, large numbers of Jews wearing the uniform of one country ended up killing large numbers of fellow Jews wearing the uniform of another. In his account of Jewish suffering in the battleground areas of the Pale of Settlement, the Jewish writer S. An-sky reports of a Jew “who had bayoneted a soldier, who, just before expiring, gasped the Sh’ma. His killer, so the story went, went mad.”

This oft-retold tale is much older than World War I, Penslar informs us. He traces its origins to a speech delivered in 1857 by Esdra Pontremoli, an Italian rabbi and educator:

Who does not remember the moving case of the French-Jewish soldier brought down to us from the stories of the Napoleonic wars? This man is lying on the ground soaked in his own blood; the shadow of death already covers his eyes; he cries out in vain. The bloodthirsty victor stands over him, lays on him a foot ready to deliver the fatal blow. Steel flashes, the vanquished man falls to his knees, a cry rings out: Shema Yisroel! And what do we see now? We see the steel fall from the hand of the victor: we see that same victor reach down to the fallen soldier, dress his wound, and help him to his feet. The final cry of the dying believer rose from the throat of the wounded man. These men recognized each other in that moment: they were brothers in faith.

Pontremoli’s own attribution of this story to an earlier era is one that Penslar doesn’t trust, since he can find no prior evidence for it. The tale only gained currency in the second half of the 19th century, he conjectures, “precisely as Jewish emancipation took hold in western and central Europe, allowing Jews to assert more comfortably a transnational identity as well as national attachments.” Penslar shows very effectively that there was a lot of middle ground between Jews of the Mosaic persuasion who disavowed any special connection with their foreign coreligionists and ardent Zionists who denied that the Jews could ever really belong to a nation other than their own. This was territory occupied for a considerable period of time by Jewish soldiers as well as civilians who took genuine pride in their Jewish fellow citizens’ service to their countries while retaining a sense of solidarity with Jews elsewhere.

Things had not always been this way. As Penslar reports, the induction of Jews into European armies was at the outset quite problematic, at least in the eyes of traditional Jews. Meeting in Prague in 1789 with some of the first Jewish conscripts into the Austrian army, Rabbi Yehezkel Landau exhorted them both to do their best to observe Jewish law and at the same time to “earn for yourselves and our entire nation gratitude and honor so that one may see that our nation as well loves its ruler and state authority.” But even as he cheered them on he sobbed. A year after he made this speech, Penslar reports, Landau showed his true colors when he “was party to a petition to the new emperor, Leopold II, that pleaded for the maintenance of the Jews’ historic privileges, one of which had been exemption from military service.”

Landau’s fancy footwork was repeated two decades later by the French Jews in the 1806 Assembly of Notables convened by Napoleon who famously declared that:

The love of country is in the heart of the Jews a sentiment so natural, so powerful, and so consonant to their religious opinions, that a French Jew considers himself in England, as among strangers, although he may be among Jews; and the case is the same with English Jews in France. To such a pitch is this sentiment carried among them, that during the last war, French Jews have been seen fighting desperately against other Jews, the subjects of countries then at war with France.

Many of the participating notables were no doubt bowing very deeply to what they perceived to be necessity and would have preferred to see the Jews remain altogether out of the fray. But there were others, too, who really meant it. And as the century wore on, there were more and more such Jews, not only in France, where Jews obtained completely equal rights, but also in countries such as Prussia, where they didn’t.

Among them one should count Rabbi Abraham Geiger, one of the founders of Reform Judaism, who insisted in Breslau in 1842 that military service “is a religious duty, indeed the highest, to which all others must be subordinated.”

At roughly the same time, Geiger was capable of dismissing the blood libel in Damascus as a matter of purely local concern. “That which goes on among the Jews living in the uncivilized countries,” he argued, “is of trifling importance only, even if it were to be of general import in these particular lands.” In later generations, however, German and other European Jews who shared Geiger’s yearning for integration into their own societies maintained a more active concern with what was going on outside of them. And they manifested the complexity of their identity, as Penslar shows, in more ways than by telling unhappy tales of Jewish soldiers killing one another.

Penslar writes that during the Franco-Prussian War, in 1870–1871, “German Jews simultaneously asserted not only German patriotism but also transnational Jewish solidarity and a particularistic religious identity.” Articles in the German-Jewish press “noted with satisfaction that Jewish soldiers served as guards for French-Jewish prisoners of war and that they attended religious services together.” In 1896, a German-Jewish defense organization published “a massive, folio-size tome” entitled The Jew as Soldier that listed “the numbers of Jews in uniform in every nation in Europe as well as the United States.” Here, Penslar writes, “The reader is struck by the placement of lists, side by side, of Jews who fought against each other, or at least whose countries were frequently enemies.” And, as he also notes, the English-language Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901–1906 contained a long entry titled “Army” that did much the same thing.

The fierce expressions of national antagonism that marked World War I tested but did not eliminate this Jewish “extranational solidarity.” At the 1935 world conference of Jewish veterans in Paris, “the assembled veterans proclaimed their love of each soldier’s native land; yet they did so as Jews,” blending “statements of love of home with a growing nationalist consciousness.” Unrepresented at this conference, however, were the German-Jewish war veterans, whose organization had been dissolved, for obvious reasons, by the Nazi government. Stung by this offense, the conference proposed to establish a village in Palestine for the orphan children of the 12,000 German-Jewish soldiers who had died fighting for Germany.

Needless to say, Jewish “extranational solidarity” in World War II, in which even more Jews fought than in World War I, bound together Jewish soldiers serving in only one of the contending alliances. “[T]here is not a single Jew fighting in the Axis armies,” proclaimed Abba Hillel Silver, in the 1941 yearbook of the United Palestine Appeal. “This was not precisely true,” Penslar carefully informs us, for there were, among others, thousands of men of concealed Jewish origin fighting for Nazi Germany and a couple of other small exceptions to the rule. He acknowledges, however, that “the prospect of Jews facing other Jews across the lines of battle, which . . . was a major theme in public conversations amongst Jews from the mid 1800s up through World War I, was no longer a visible dilemma.”

The transnational identity on which Penslar focuses in his final chapter is the one that bound the world’s Jews together in a joint struggle for Jewish independence. “During World War II,” he writes, “and during the years of Israel’s struggle for statehood, the line dividing a ‘diaspora’ from an ‘Israeli’ fighter was porous to the point of dissolution.” Unfortunately, both in the diaspora and in Israel, mythologists and historians of the matchless “sabra” have largely obscured the extent of the contribution made in Israel’s War of Independence by Jewish soldiers who weren’t homegrown. There is, of course, one great exception to this rule. The legend of Mickey Marcus, the West Point veteran who died in the war (depicted by Kirk Douglas in the 1966 film Cast a Giant Shadow) still flourishes. But this hero, whose story Penslar retells at some length, was not alone.

Office, Israel.)

There were, to begin with, the numerous Haganah leaders “who had cut their fighting teeth in European armies during the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution.” Of these, Penslar singles out for special attention Sigmund Friedman, a former head of the Austrian World War I Jewish veterans’ association who had been arrested around the time of the Anschluss but was released “largely thanks to intensive lobbying efforts by Jewish veterans’ groups throughout the world.” After changing his name to the quintessentially sabra moniker, Eitan Avisar, he became the Haganah’s deputy chief of staff and “created a nationally organized militia and strategy out of what had been localized units and defensive schemes.”

In addition to such individuals there were the foreign recruits who came from Europe to Palestine in the framework of Gahal as immigrants, as well as 3,500 mostly Jewish volunteers who came mainly from the United States, Canada, and South Africa. Known as members of Machal, they “supplied the bulk of the pilots and crew for Israel’s embryonic air force, which played an essential role, not as a combat force so much as a transportation corps.” Perhaps even more vital to the struggle for Israel’s independence was the assistance provided by diaspora Jews in the surreptitious purchase and acquisition of weaponry: “86 percent of the cost of Israel’s arms purchased abroad in 1948,” Penslar tells us, “was borne by foreign sources.”

Ending on this note, Penslar’s narrative might be mistaken for Zionist triumphalism, celebrating the ultimate coalescence of the disparate forces of the Jewish world in the service of a Jewish national project. But this is by no means the intention of this accomplished historian, who divides his time between the University of Toronto and Oxford and has made very significant contributions to both the history of Zionism and modern Jewish history in general. Penslar does want to demonstrate the crucial link between the experience of diaspora Jews in Gentile armies and the origins of Israel’s military. But if there is any cause that he is seeking to uphold in Jews and the Military it is not that of Israel but of the Jewish soldiers of the diaspora, who have been “blotted . . . out of Jewish collective memory.” Penslar complains both about “Jewish historical writing in North America,” which has “steadfastly neglected Jewish soldiers,” and Israeli scholars, who have “usually considered the diaspora Jewish soldier to be too inconsequential for serious attention.”

Penslar hopes that his new book will help to rectify this situation, and perhaps it will, at least among Jewish historians, the primary audience of this learned tome. Many of them will no doubt be tantalized into pursuing the innumerable fascinating leads that Penslar provides. (Who knew, for instance, that Bernard Lazare, the famous Dreyfusard, had a brother, an officer in the French Army in Indochina, who was “disgusted to wear the same uniform as that of Dreyfus’ tormentors”?) But it is hard to imagine a similar reaction among the general public. Its lack of interest in the history of Jewish military accomplishments in the diaspora is, as Penslar notes, glaringly evident.

In 1954, the Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America purchased a modest building off the Mall in Washington, D.C., and four years later received a congressional charter to establish a museum of American-Jewish military history. The museum attracts a few thousand visitors per year, mostly veterans or the families of veterans, or groups of Jewish day-school students from the Washington area. Nearby, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum receives some two million visitors per year. In Toronto, in recent years vast sums of money have flowed into a new Holocaust museum and educational center, while far more modest plans to construct a monument honoring Canadian-Jewish soldiers of World War II were shelved owing to a lack of funds.

Penslar is not at a loss to explain this state of affairs. “Since World War II,” he writes, “Jews in North America have lost the thrill induced by gazing at their menfolk in uniform.” Freer than ever before from overt anti-Semitism, they feel little pressure “to produce apologetic literature, including documentation of the Jews’ historical contribution to the military.” Penslar does point to signs of an uptick in American Jewish involvement in the military. In recent years, he notes, “1 to 2 percent of West Point’s cadets and midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy were Jews.” This is not very far from the total percentage of Americans who are Jewish. Then again, it pales in comparison with the reported 23 percent of students attending Ivy League colleges who are Jewish and doesn’t really seem like a harbinger of any significant change. The preoccupying concerns and aspirations of American Jewry are decidedly irenic, so it is not surprising that its collective memory, such as it is, is directed elsewhere.

Israel is, of course, a more complicated story. The parade of elderly Russian-Jewish veterans of World War II down Israeli streets in recent decades surprised “Israelis whose education has made little room for heroism within the framework of a diaspora army” and has led to the erection of a memorial to the Red Army in World War II in Netanya. And in April of 2012 Tel Aviv’s Diaspora Museum devoted an exhibition to “the foreign volunteers who manned the ships that brought illegal immigrants to Palestine and who fought in Israel’s War of Independence.” Penslar sees this latter commemoration as one of the signs that the “classic Zionist deprecation of the diaspora” is giving way, at least “among Israel’s political and cultural elites,” to a more positive attitude. But whether this will filter down to an Israeli public in which the opposite point of view is deeply rooted is something one must be permitted to doubt.

Suggested Reading

An Israelite with Egyptian Principles

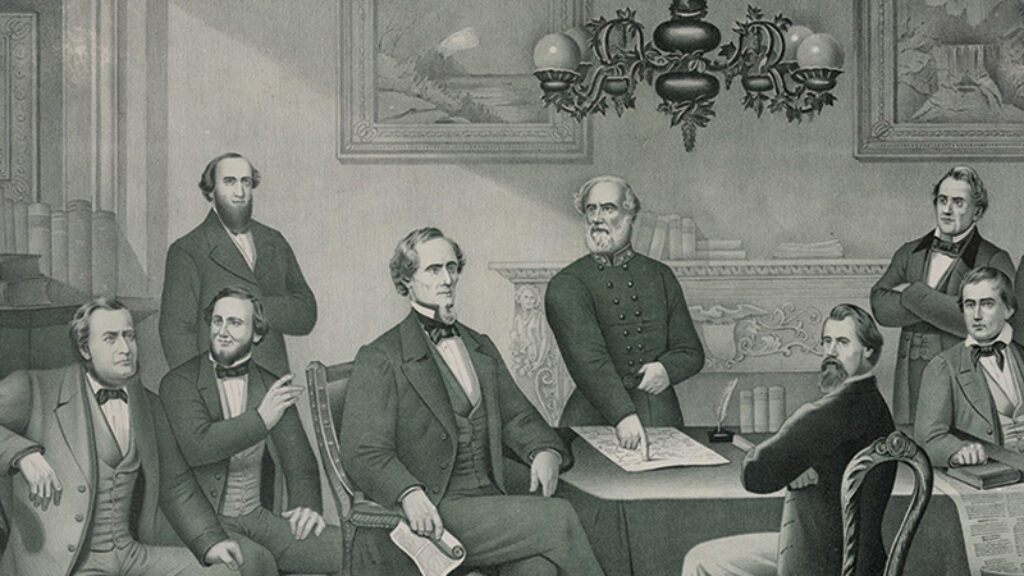

Judah Benjamin was a brilliant New Orleans lawyer who became the most important cabinet member in Jefferson Davis’s Confederate government. He was, Senator Benjamin Wade correctly declared, one of the “Israelites with Egyptian principles.”

Animal Foible

The author of Life of Pi trivializes the Holocaust.

Adventure Story

The story of Hebrew is a great story because there is nothing inevitable about it. Whether it was the period of the Bible or the Mishnah or Maimonides, there was always a danger, often the likelihood, that Hebrew would be lost in the break-up of great communities and subsequent migrations.

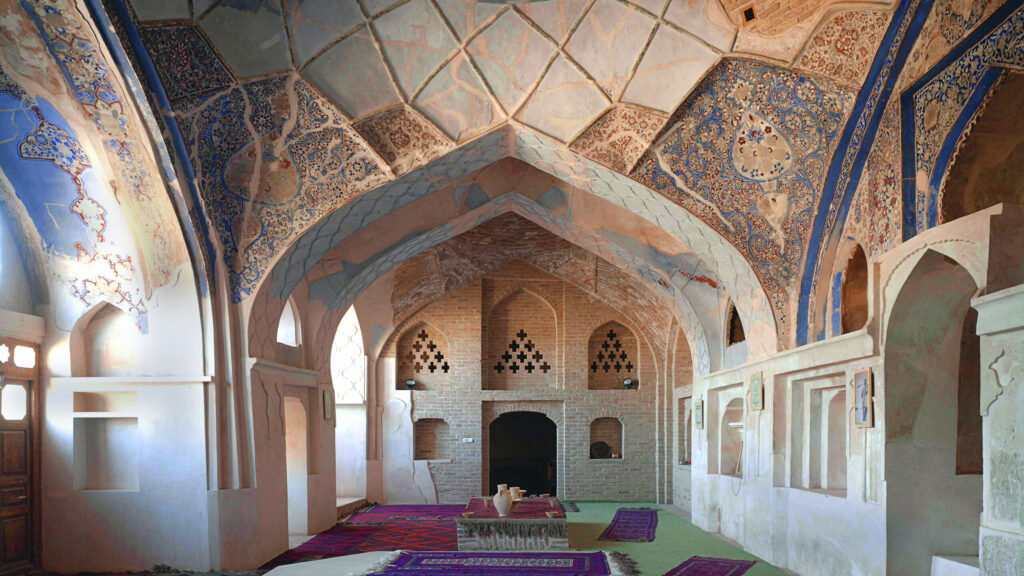

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In