Lamed-Vovnik

Some writers who take the Holocaust as their subject return to it again and again: Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, Imre Kertész. Others visit it just once. The Holocaust “seems to expel certain writers from its provenance after a single book,” the literary scholar Alvin Rosenfeld has observed. For writers like Jerzy Kosinski (The Painted Bird), Sarah Kofman (Rue Ordener, Rue Labat), and Cynthia Ozick (The Shawl), one devastating engagement with the Holocaust seems to have been sufficient. Until now, André Schwarz-Bart—a French-Polish Jew who joined the Resistance as a young teenager after his parents were deported to Auschwitz and killed—has been the definitive example of this category.

Schwarz-Bart’s remarkable first novel, Le dernier des justes (The Last of the Just), which was published in France in 1959 and awarded the Prix Goncourt, re-imagined the legend of the Lamed-Vovniks. The legend, which has its origins in the Talmudic statement that thirty-six men “daily receive the Divine Countenance,” holds that in each generation there are thirty-six “just men” who are responsible for the preservation of the world (the Hebrew letters lamed and vov correspond to the number thirty-six). As Gershom Scholem explained in a classic essay, these men are normally depicted as both unaware of each other’s presence and also ignorant of their own special status. In some versions of the legend, the future of the world itself relies upon their good deeds. In times of great danger, according to yet another version, a Lamed-Vovnik can use his powers to defeat the enemies of the Jews.

In Schwarz-Bart’s account, the Levy family of Zemyock, a town in Poland, is blessed—or cursed—by the presence of a just man in each generation. Unlike the Lamed-Vovniks of tradition, many of the Levys are aware of their exceptional qualities, which largely consist in an almost supernatural ability to feel compassion for the sufferings of others. “The Lamed-Vov are the hearts of the world multiplied,” Schwarz-Bart writes, “and into them, as into one receptacle, pour all our griefs.” To them, “the spectacle of the world is an unspeakable hell.” Andalusian Jews in the seventh century were known to venerate a teardrop-shaped rock, said to be “the soul, petrified by suffering,” of one of the Lamed-Vovniks. Another Hasidic story holds that when a just man rises to heaven, God must warm his frozen soul for a thousand years before it can open itself to paradise. “It is known that some remain forever inconsolable at human woe, so that God Himself cannot warm them,” Schwarz-Bart continues. “So from time to time the Creator . . . sets forward the clock of the Last Judgment by one minute.”

Schwarz-Bart’s chronicle of Jewish suffering starts with a massacre in York, England, in 1185 and continues through the Holocaust, focusing on the fate of Ernie Levy, the last of the line, who dies at Auschwitz. The novel’s style has the dreamlike quality of folklore; its scenes of torment are depicted as if in a Chagall painting. Perhaps this is what enables Schwarz-Bart to take the book’s most dramatic step: He imagines the gas chamber itself, a place few novelists have permitted themselves to enter. Depiction of the gas chamber has come to be regarded as the last remaining taboo of Holocaust literature—impossible to represent, because no one survived to tell the story. As if offering penance for his transgression, Schwarz-Bart ends his novel with a now-famous passage offering a broken prayer for the “millions, who turned from Luftmenschen into Luft“: “And praised. Auschwitz. Be. Maidanek. The Lord. Treblinka. And praised. Buchenwald. Be. Mauthausen. The Lord. Belzec. And praised. Sobibor. Be. Chelmno. The Lord. Ponary . . .” And so on. And so on. And so on. Schwarz-Bart’s litany of suffering has the effect of transforming the reader into a kind of Lamed-Vovnik, a vessel shuddering with the empathy of the ages.

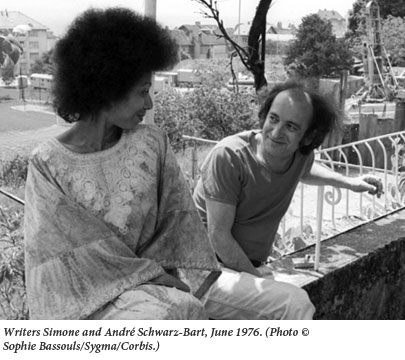

The Last of the Just has dropped off the radar in recent years, but at the time of its publication it was an international bestseller, and was immediately recognized as a classic of Holocaust literature. Yet Schwarz-Bart appeared to have had enough of the subject. After his marriage in 1961 to Simone, a woman from Guadeloupe, he wrote several books together with her, including Pork and Green Bananas and an essay series called In Praise of Black Women. She may also have collaborated with him on his second novel, A Woman Named Solitude, about a young West African girl sold into slavery who becomes a martyr figure similar to the Lamed-Vovniks. He died in 2006 without publishing another book about the Holocaust.

Until now. In an introductory note to The Morning Star, Simone Schwarz-Bart explains the story of “the genesis of this work, which very nearly didn’t exist.” Her husband, she writes, would dictate episodes to her and their son Jacques, but would then destroy them. “We asked ourselves . . . what on earth is stopping him from finishing this book?” In the book’s final pages, its main character, a Holocaust survivor, answers the question himself. Clearly a stand-in for the author, he has lived in French Guyana and then in the Caribbean; after publishing a few books, he now lives like a “schlemiel, a man who had lost his shadow.” He is “in mourning for literature, in mourning for himself,” because he has spent his life trying to answer the impossible question of how to talk about Auschwitz. “How to express his impressions of a heap of dead bodies? Or simple: a day in Auschwitz?” By the end, he has two chests full of manuscripts that comprise hundreds of different approaches, all ultimately unsatisfactory.”

What made this writer, who once did not hesitate to represent the very nearly unrepresentable, so reluctant to continue? Simone Schwarz-Bart writes that after André’s death, she realized that for her husband, finishing his book meant, in some way, abandoning the dead. “I have to keep all of that inside me,” he wrote in a note that she found among his papers. “So much work, so many vigils, so much pain, day after day, night after night, for nothing.” Like the Lamed-Vovniks of his first novel, Schwarz-Bart suffered on behalf of his characters, unable to admit that their suffering was without meaning.

Yet in the meantime Schwarz-Bart had come up with an extraordinary device to solve his literary problem: He wrote his wife into his book. She appears as a researcher in the year 3000, after the death of planet Earth through contamination with nuclear waste, overpopulation, and finally some vague, unspecified calamity involving bombs. Its inhabitants, who had already “taken to the stars” and there reconstituted Earth’s atmosphere, are dispersed throughout the galaxy. There, mysteriously, they have discovered the secret of immortality, and reproduction takes place through cloning. But they are nostalgic for the old earthly traditions, and some of them return to the planet to dig through archives.

It is in the ruins of “a foreign country, known successively by the names of Judea, Palestine, Israel,” that a historian bearing Simone Schwarz-Bart’s middle name discovers “traces of a strange massacre that had occurred about a thousand years earlier.” Sorting through chests of manuscripts found in the attic at Yad Vashem, she is astounded by the records of this lost civilization of wanderers, against whom “nearly all the tortures ever invented by men since their birth in the Rift Valley were directed . . . during the brief period of the Great Massacre.” And yet, “even on the edge of the abyss,” these men and women wrote poems and stories; they conducted clandestine religious services and schools. “The people of wanderers had disappeared: but they had lived, humbly, beautifully, as best they could.”

The text derived from the wreckage—it is unclear whether the researcher discovers it or writes it herself—makes up the body of Schwarz-Bart’s slender book. Even more elliptical than The Last of the Just, it tells the story of the Polish village of Podhoretz, from the mid-nineteenth century until its destruction in the war. Again it follows a family line, this time the descendants of a man named Haim Yaacov, who are unexceptional apart from their capacity for mystical experience. The “inexplicably merry” Haim Yaacov “looked at a face and heard a melody, he looked at the sky and heard a different melody and, even when he closed his eyes, the melody of the world did not desert him.” Later he will spend two years reconstructing a broken violin and another two learning how to extract a “Jewish sound” from it, but when he does his music attracts people from miles around.

Like The Last of the Just, The Morning Star draws on Jewish tradition. The prophet Elijah appears at various key moments; when the Nazis invade, Haim Lebke expects an angel to stay the hands of the Germans as it once did for Abraham when he was about to sacrifice Isaac. As the war progresses, the Jews in the ghetto wonder if the world is coming to an end, a prospect that evokes both dread and joy. “All these people, all these events, seem today to be covered in a mantle of sweetness, tenderness, like the golden veil of legend,” the narrator comments.

Yet the book never veers into kitsch or treacle. Schwarz-Bart’s language can be downright earthy, but more often it attains a lyricism that feels all the more otherworldly in the brutal context of its subject. In the final Auschwitz scene, Haim Lebke, lying ill in the infirmary, has a vision of himself back at home, at the Shabbat table; as he reaches for the food, it turns to ashes.

And as he expressed astonishment to his father, to his mother, to his brothers with their ever-dreamy eyes, wonderfully warm and loving, the ashes of evil also claimed the humans, one after the other, reducing the tablecloth to dust, the glasses, the plates, the knives and forks and spoons, the chairs, doors and windows, and the house and the trees, the mountain, the plain in the distance and the clouds, the whole wide world, right up to the invisible stars.

Schwarz-Bart’s ambivalence about the very act of writing about the Holocaust is all the more perplexing in the context of this exquisite book. Perhaps he felt some residual guilt about the best-selling success of his first novel. But it may also have had something to do with his outlook on the Holocaust itself—and his decision, on its face bizarre, to frame his Holocaust story in a narrative of future dystopia. The real dystopia, it turns out, may not be an Earth without human beings, but rather an Earth without Holocaust survivors. “The day the last survivor disappeared, there would be nothing left but images and words,” one character says towards the book’s end. “Then the words and images would die, and the earth itself would stop turning.” The survivors, then, are like the Lamed-Vovniks, responsible for the future of the world. Their compassion, their suffering, is Earth’s motor.

So we need stories about the Holocaust, then, regardless of the cost of telling them. “Literature dealing with the inhuman should conform to the human heart, show humanity toward the reader,” Haim Lebke, speaking for his creator, concludes toward the novel’s end. As a result, it has to “leave an area of shadow hovering and introduce or enhance the part of light, so that the area of shadow that subsists is bearable to the eye of the average reader” without risking his transformation into a petrified teardrop.

The conflict over the ethics of aestheticizing horror is as old as genocide itself, but Schwarz-Bart has come up with a unique literary solution. For it is through her studies of the Holocaust that the clone who frames his story realizes what was lost with the transformation of human beings into immortal but emotionally insensate automata. She longs to experience the “relentless love of life” that she finds in these texts; in comparison with a life lived coldly, even anguish in the face of death can feel like a kind of exhilaration. What finally emerges from Schwarz-Bart’s book is a celebration of life in all its transience, as the clone decides to return to Earth to be reborn as a member of the lost race of humanity—thus metaphorically fulfilling Haim Lebke’s dream that the Jews in the ravine where he was nearly slaughtered be resurrected. With this vision of death and rebirth at its heart, The Morning Star—agonized over by Schwarz-Bart for years and finally reaching us only posthumously—is the most hopeful work of Holocaust literature that I have read.

Suggested Reading

From the Great War to the Cold War

The facts of Hans Kohn’s life are so extraordinary that it almost seems as if the first half of one remarkable figure’s biography had been spliced together with another’s in the second part.

Kidnapped!

When Ruth Blau met with Khomeini to secure the safety of Iranian Jews, it was only the latest extraordinary meeting for the fifty-seven year old Resistance spy turned convert turned kidnapper turned anti-Zionist turned Israeli agent.

Revisiting Herman Wouk’s City Boy

Remembering Herman Wouk's "gentle mockery at the shopworn pretensions of bohemian poseurs and ethnic Jews passing as nonhyphenated Americans."

Perish the Thought

Bruno Chaouat dares to ask whether, given the moral autism of so many of Theory’s luminaries when facing the basic political questions of our time, his own romance with it has been a similar waste.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In