Fateless: The Beilis Trial a Century Later

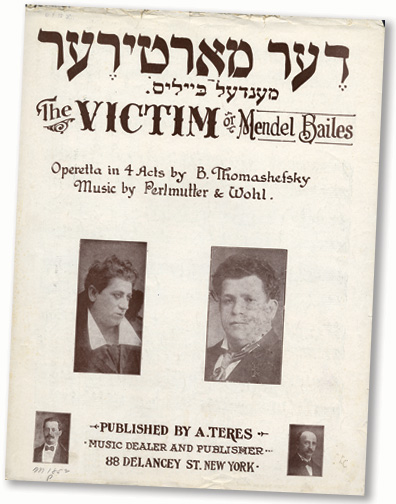

In the fall of 1913, a hundred newspaper reporters packed the Kiev courtroom where for five weeks Mendel Beilis was tried for the murder of a 12-year-old whose body had been found, in the spring of 1911, in a cave near the brick factory where Beilis worked. He was accused of having murdered the boy in order to use his blood to make matza. That Thanksgiving, in New York, no fewer than six Yiddish-language theaters staged plays about him. Mendel Beilis’ fame was lavish, if bitter and short-lived.

Nearly all of the journalists covering the proceedings, including most of those representing Russia’s anti-Semitic press, saw the prosecution’s efforts as corrupt, the by-product of mendacity at the highest governmental levels, a terrible, stupid tale of a Jew caught in the vise of dark medievalism. Beilis suffered more than two years of imprisonment before being exonerated by a jury that decided that, while he was innocent, a ritual murder had actually occurred.

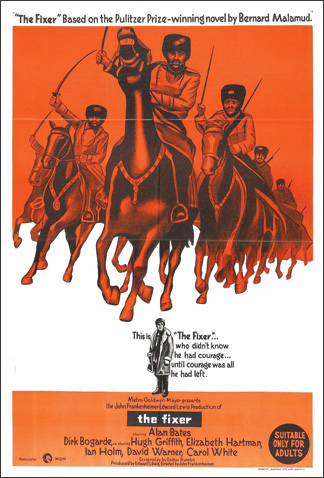

Yet here, as is so often the case, life’s protagonists disappoint, a reminder that their brush with history was an accident, a stumble. In art, certainly in film, those caught up in history’s sagas tend to look like Robert Redford (or at least Alan Bates, who played the Beilis character in the adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s novel The Fixer), but more often than not, they look like the stooped, chinless Beilis.

And his is a tale, arguably, still more confounding than most. “The greatest handicap . . . is its improbability,” observed Maurice Samuel on the difficulty of writing Blood Accusation: The Strange History of the Beiliss Case, “and by this I mean not only the inanity of the attempt to prove the Blood Accusation but also the entire structure of the conspiracy. A bare recital of the facts, however strongly documented, would leave the reader incredulous.”

First of all, Beilis himself was miscast: The poster-child victim of anti-Semitism in the last years of the Romanovs was a Russian military veteran with stalwart Russian friends and warm supporters even among the regime’s vocal anti-Semites. Beilis yearned for the companionship of Russian prisoners to share his cell because he found them, on the whole, kind and sympathetic. Once his trial concluded, he was so sought after in Kiev by non-Jews and Jews alike that tram conductors would call out, “Take Number 16 to Beilis’.”

Then there was the story’s femme fatale, Vera Cheberiak, who was the likely murderer of the boy. Nervy, tempestuous, a voracious liar, and serial philanderer, she was a petty thief who appears to have tried to cover up her thievery with the butchery of a playmate of her son who seemed likely to inform the authorities. Hardly anyone in the saga resembles, say, Rasputin, who really looked his part (though Cheberiak does seem to have also had mesmerizing eyes), not even Tsar Nicholas II, whose preoccupation with Jews was more aimless and muddled than many believed at the time and later.

Years ago the formidable historian Benzion Dinur, Israel’s education minister under David Ben-Gurion, argued that nearly every aspect of Hitler’s Final Solution had been previewed by the tsarist regime in its final years when the Beilis trial occurred. Here was a police state pursuing a concerted policy of persecution employing both the instruments of a vast bureaucracy and pogromist hoodlums to level a huge Jewish community. Such sweeping historical assertions can no longer be sustained in light of recent historical work that portrays a Russian regime less comprehensively focused on Jews or, for that matter, much of anything else.

But then how is it that Mendel Beilis stumbled into posterity, and what, if anything, do his travails teach about the larger contours of Jewish fate in the Russian Empire? In the wake of post-Soviet opening of archival material, the details of this affair can finally be reconstructed, in its dizzying twists and turns, nearly hour by hour. The story that emerges challenges, in ways small and large, long-regnant assumptions about the rhythms and routines of Jewish life in Russia, its miseries as well as its pleasures.

Beilis’ story pushes into bold relief features of a Russian-Jewish life both alarmingly worse but also strikingly better than is often imagined. By far the best years of his life were those he spent in Kiev managing a brick factory, supervising non-Jews who lauded him as an exemplary manager, sometimes even as a friend, and who enthusiastically spoke on his behalf in court. True, he would be persecuted by an insipid and bumbling Russian bureaucracy, but he also found defenders from nearly every sector of Russian civil society. In its own way, Beilis’ life is something of a Russian-Jewish success story. He was a happy man before he was made into a miserable one.

Beilis worked in a brandy distillery before he was drafted into the infantry at 18 and sent to Tver for a few years. After he was discharged, he married and worked for his wife’s uncle, who owned a brick-making kiln in a town near Kiev. One of the city’s Jewish grandees, Jonah Zaitsev, hired him away to manage a new brick factory, where he worked for 15 years evidencing barely a hint of discomfort with his Christian neighbors; during the 1905 Kiev pogrom a local priest protected him and his family from harm. His oldest son, one of five children, attended a secondary school with non-Jewish schoolmates at the local gymnasium. In his memoir, published in Yiddish and recently reissued in English, Beilis wrote, “I thanked the Lord for what I had, and was satisfied with my secure and respectable position.”

Kiev had long been a magnet for Jews, mostly petty traders and laborers, but also some merchants and a thin stratum of very wealthy Jews, including some of the richest in the empire. Residency restrictions made it impossible for all but the most privileged Jews to live there before the late 1850s, but eventually they made up 11 percent of the city’s population (over 30,000), mostly clustered in wretched outlying districts packed with tiny workplaces and factories.

One hundred Jews were murdered in the Kiev pogrom of 1905, among Russia’s most vicious anti-Jewish attacks. Still, it remained afterward, too, a place for the ambitious or restless to settle, a boisterous, crowded city where money could be made and where a decent life was at least conceivable. Jews filled the city’s streets as small shopkeepers, carters, and peddlers (most of Kiev’s staggeringly numerous liquor shops were run by Jews).

Russia’s most vocal anti-Semites claimed that Kiev was overrun by Jews, who would soon turn it into another Berdichev. Jews complained they were made to feel unwanted because anti-Semites dominated the municipal government and much of the local press. Kiev had a richer array of anti-Jewish organizations than found elsewhere, though they often battled one another often with greater intensity than they fought Jews. Among the most visible was the Union of the Russian People, or the Black Hundreds, who would play a prominent role in stirring up charges against Beilis.

In March 1911, the body of 12-year-old Andrei Yushchinsky had been discovered in a cave 300 yards away from Mendel Beilis’ office. “As I looked through my window,” he later wrote, “I saw people hurrying somewhere, all in one direction.” This struck him at the time as odd, but he returned to his receipts. The investigation dragged on, little noticed beyond officialdom, and unlinked to Jews except, at least initially, by a handful of local fanatics.

At first the murder investigation was a straightforward one, albeit increasingly thwarted by local authorities, homegrown racialist pressure groups, and eventually by some in Saint Petersburg. Two police investigators following credible leads that brought them to Cheberiak’s doorstep were fired and even brought up on charges. One spent time in jail; both were disgraced.

A coroner’s report—two were produced, in fact—soon made it clear that the body had been stabbed repeatedly; the boy suffering a wild, frenzied attack even after he had died. From the outset, the conceivability of ritual murder was deemed sufficiently compelling to have been considered. The coroner investigated whether blood had been drained from the body after death, but found that this hadn’t occurred.

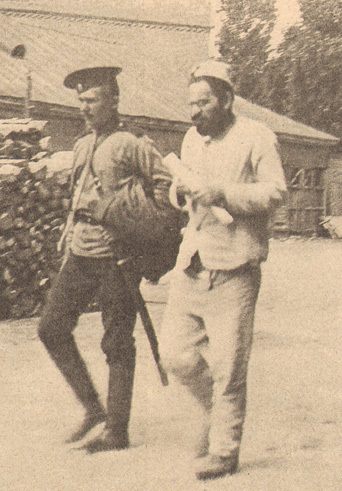

Then in, July 1911, Minister of Justice Ivan Shcheglovitov gave the nod to pursue this as a ritual murder case. Fifteen police were dispatched to arrest Beilis, waking him in the middle of the night. Later, when he was sent from the local police station to prison a couple of miles away, he was accompanied by a solitary officer who, deciding that Beilis shouldn’t be compelled to walk the distance, took him by public trolley. A neighbor of Beilis’, who was a member of the Black Hundreds wearing the anti-Semitic group’s pin on his lapel, embraced and kissed Beilis and announced to Beilis and the other passengers that he shouldn’t fear because everyone knew he was innocent.

Meanwhile, in September 1911, P. A. Stolypin, minister of internal affairs and chairman of the tsar’s Council of Ministers, was shot and killed in front of Nicholas II, in the Kiev Opera House. The assassin was an anarchist revolutionary, who was also an informer for the secret police, named Dmitri Bogrov. Bogrov was born into a family of converted Jews who were nonetheless seen as Jewish, and his origins seemed likely to further exacerbate anti-Jewish feeling.

The trial itself was bizarre. Witnesses for the prosecution acknowledged on the stand that they’d been bribed or in other ways compelled to testify against Beilis; the prosecution eventually could think of no better argument than that he was in cahoots with Vera Cheberiak, whom he clearly didn’t know. The jury was rigged, and the judge showed unabashed bias.

Despite the coroner’s evidence, eventually Beilis’ defense team would feel compelled to insist that Yushchinsky’s body had not been drained of its blood, leaving the impression—unfortunate, if also under the circumstances perhaps inescapable—that had such drainage happened it would have pointed toward Jewish culpability. At the time those believing in Jewish ritual murder held that the practice was maintained by a small secretive sect of Hasidim. Much effort on the part of Beilis’ prosecution would consequently be devoted to linking the ritually indifferent Beilis—he worked on the Sabbath—to Hasidism. That Beilis knew a hay dealer named Shneyerson, who despite his last name was not related to the Lubavitcher dynasty and was, in fact, no less indifferent to the strictures of Jewish practice than Beilis, would occupy many, many hours of the prosecution’s time.

During the trial, an acclaimed expert for the prosecution who affirmed that ritual murder was mandated in the Talmud proved unable to name any of its 63 tractates. In a rare moment of levity, an anti-Semitic priest with pretensions to vast textual expertise was asked when Baba Batra lived. (The question was, of course, a trick: Baba is Russian for a peasant woman, and Baba Batra is perhaps the best known of all talmudic tractates.) The befuddled witness made it clear that he had no idea what he was being asked. Nearly all the many Jews in the room—except, that is, for Beilis, who sat stone-faced during nearly all the 34-day ordeal—laughed openly. Prosecutors privately recorded later that day that they knew they’d botched the testimony. But Beilis’ lawyers, a stellar team made up of some of the leading jurists in the empire, all but one of them non-Jews, were convinced the jury would convict Beilis even though the prosecution had presented no solid evidence at all.

Split down the middle six to six, Beilis’ jury declared him innocent, since Russian law stipulated that such decisions rendered the accused free. But it also decided that a ritual murder had transpired, which permitted both sides to claim victory. Still, in stark contrast to the Dreyfus case in France, essentially all sectors of Russian society, except the far right, applauded his release. Russia’s most prominent Jew-haters—the term “honest anti-Semite” was used at the time to describe them—felt the trial a terrible embarrassment and a setback.

Why did it happen? The reason for Beilis’ selection was clear: He was the only Jew within spitting distance of the murder scene, living, as he did, in a district where Jewish residency restrictions were still in force. But little else about this episode makes much sense. Why focus on a Jew? Why the support given to the prosecution from the highest reaches of the Russian government, most consistently by Minister of Justice Shcheglovitov? And why proceed with it for years despite the fact, now clearer than ever because of the availability of archival sources, that those prosecuting Beilis knew him to be innocent?

At the time of the trial, the answers seemed self-evident: It was a plot by the tsarist government led by resolutely anti-Semitic Nicholas II, which sought to use Beilis as a distraction from mounting radicalism, or, perhaps, as a way of deflecting opposition to the restrictions on Jewish residency in discussions of the Pale of Settlement, or perhaps simply to set in motion a murderous wave of pogroms.

Books on the case, starting with Alexander Tager’s 1933 path-breaking Russian-language study The Decay of Czarism, concurred that the sordid business was the work of a regime on the skids. And still many years later, this is essentially the viewpoint offered in Edmund Levin’s new book, A Child of Christian Blood: Murder and Conspiracy in Tsarist Russia: The Beilis Blood Libel. As he sees it, the regime sought to persecute Beilis because of its single-minded policy of discrimination against Jews, which was born of the need to impose unity onto a multinational, pre-modern state. And, as he sees it, all this was traceable to Nicholas II himself.

Levin relates the mesmerizing details of the Beilis case with sure command of the archival material. Unfortunately, his historical scaffolding is rickety, the product of outworn notions about the workings of late imperial Russia. The trial itself is superbly described, but the larger context in which it was conducted is scanted and the complex social and political terrain is flattened. His treatment of Nicholas II’s personal involvement is indicative of the book’s problems. Although Levin acknowledges the tsar’s sentiments are “hard to discern,” he nonetheless insists “it stood to reason that a man who believed a divine whisper urged him to persecute the Jews was likely to welcome an endeavor that sought to prove their fanatical malevolence.” Servitors like Shcheglovitov must have “believed he was doing what the tsar wished him to do.”

A first-rate summary of how leading historians of the period now view the trial’s backdrop can be found in Robert Weinberg’s excellent new volume, Blood Libel in Late Imperial Russia: The Ritual Murder Trial of Mendel Beilis, which tells the story through well-chosen and translated primary documents together with an insightful analysis. As Weinberg observes, almost half a century ago UCLA historian Hans Rogger, whom Levin cites often but mostly misunderstands, made a convincing case for a drastically different scenario. As Rogger wrote, first in 1966 in the journal Slavic Review and then in his groundbreaking volume Jewish Policies and Right-Wing Politics in Imperial Russia, while Nicholas II’s antagonism toward Jews certainly ran deep there is no evidence that the tsar instigated the case against Beilis. When the case was first launched, in 1911, he was not preoccupied with the threat of radicalism, and there was no need to thwart the prospect of the abolition of the Pale of Settlement then, which would never happen anyway. Moreover, the widespread belief that the tsars had been behind the pogroms had been thoroughly dislodged by decades of research. Little, if anything, so terrified Russian rulers as much as mass violence in the empire’s towns or villages. As Rogger noted:

There had been no grand design; there had not even been a tactical plan. There had been an experiment, conducted by a small band of unsuccessful politicians and honest maniacs to see how far they could go in imposing their cynicism and their madness on the state. They had succeeded beyond all expectation.

The whole, wretched enterprise was initially launched by fanatics led at first by an unstable, charismatic seminary student named Vladimir Golubev, whose machinations would mesh, likely much to his surprise, with those of the minister of justice, as well as others in the tsarist administration. This ménage of the obscure and consequential acted without any cue from Nicholas II, though some of them were no doubt convinced that their activity could provide direction for a rudderless regime.

Golubev and fellow “honest maniacs” distributed anti-Jewish leaflets at Yushchinsky’s funeral, interfered with the police investigation of Cheberiak, and pressed to have detectives unconvinced of Beilis’ guilt fired or exiled, until the case took on a life of its own. This happened when others less delusional and more calculating and influential linked themselves to it. They did so, Rogger argued, not because they were enlisted by the tsar but, rather, because they had long ago lost faith in his or his family’s capacity to hold Russia in check, and because they were now casting about for new, untested sources for Russian solidarity in the face of mounting threats internal as well as external.

If, as is almost certain, Shcheglovitov knew that there was no such thing as ritual murder, his unwavering commitment to the Beilis case and to the men who had inspired it was yet a matter of principle. Or, rather, it was the search for a principle, for a common belief which would rally and bind together the disheartened forces of unthinking monarchism . . . Lacking a monarch who could have embodied the autocratic principle with vigor and infectious conviction, they had only anti-Semitism and the notion of universal evil, with the Jews as its carriers, to make sense of a world that was escaping their control and their intellectual grasp . . . Judeophobia was to be the catechism and ritual murder the credo quia absurdum which would make possible a comprehensive attitude not only toward Jews, but toward men in general, toward history and society. Anti-Semitism was to become, in Sartre’s words, at one and the same time a passion and a conception of the world.

In Rogger’s view, Jews in Russia’s last years before the outbreak of the First World War faced a dilemma far less coherent or coordinated than widely believed then or now, but also in its own way more ominous than they could have known. Anti-Semitism was not the engine of statecraft, but it was also no longer merely the inchoate plaything of the politically marginal. Russia’s very salvation was linked to a campaign against the Jews. Beilis was the test case. As an experiment it failed miserably (he was acquitted) but it also succeeded (half the jury was convinced of his guilt with all of Russia made to talk about Jewish perfidy).

The question of Beilis’ guilt was irrelevant to his accusers: In this respect their calculations were similar to those, also on the Russian ultra-right, who stitched together and then promulgated the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” They, too, knew well that the words attributed in their forgery to the invented Elders had never actually been spoken, but they were nonetheless convinced that they were as close to the real, terrible plans of the Jews as they’d likely ever know. The infamous forgery, like Kiev’s rigged trial, both pockmarked with lies and misdeeds, were justified by the overarching reality of Jewry’s unspeakable machinations.

So many touched by the affair ended badly. The Kiev prosecutors earned promotions once it was concluded, but the 1917 revolution consumed nearly all of them. Both Minister of Justice Shcheglovitov and Vera Cheberiak were sought out and murdered by Bolsheviks. In post-Soviet Russia, the murder victim Yushchinsky has been recast into a sainted figure, who is again widely believed to have been murdered for Jewish ritualistic purposes.

Even Bernard Malamud, whose fictionalized account of the trial, The Fixer, won both the Pulitzer and National Book Awards in 1967, and has been recently republished in The Library of America’s edition of his work from the 1960s, reaped his share of misery. Once the book appeared, he was hounded by Beilis’ heirs, and decades after his death, they hound him still in the new edition of Beilis’ The Story of My Sufferings, which was privately released by the family three years ago under the title Blood Libel: The Life and Memory of Mendel Beilis. A new epilogue to the memoir insists that all that’s worthwhile in Malamud’s novel is plagiarized while taking it to task for departing from the details of Beilis’ life. A list of Malamud’s transgressions is provided that reads like the melding of a Soviet literary commissar’s report with that of an obtuse Jewish communal staffer. These charges first surfaced on the novel’s appearance, the same year Maurice Samuel’s Blood Accusation was published. In response Malamud sought, without success, to have the memoirs, which were no longer under copyright, reissued. (Perhaps he felt uneasy with the sometimes painfully close resemblance between his prose and that of Beilis’—even paranoiac relatives can have genuine cause for complaint.)

Malamud, who picked up bits and pieces of Russian-Jewish life while researching his novel and then went off to the Soviet Union for a week or two to glimpse some of the sights, produced a very American Jewish book, certainly not a history. Its primary inspiration, as he later admitted, was the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, and his portrait of Jewish life under the tsars is, unsurprisingly, flat, sparsely informed, and much influenced, as he gratefully acknowledged, by the flaccid anthropological study of Eastern European Jewry Life Is with People: The Culture of the Shtetl. (On the peculiar history of that book and its principal author who was, among other things, a Stalinist spy, see my essay “Underground Man: The Curious Case of Mark Zborowski and the Writing of a Modern Jewish Classic,” which appeared in the Summer 2010 issue of this magazine.) In fact, Malamud lifted passages almost directly from Life Is with People, much as he did from Beilis’ memoir. The novel’s sinews are laid out in Philip Davis’ recent, superb biographical study, Bernard Malamud: A Writer’s Life.

The enduring power of The Fixer is in its vivid portrait of protagonist Jakob Bok’s unrelentingly bitter fate. Like that of so many of the noble, hapless protagonists of Malamud’s fiction, it is the by-product of one, perhaps two small but fatal missteps: He nearly has sex with the daughter of a Black Hundreds’ devotee—a drunk and lout far more uncompromisingly bigoted than was Beilis’ real-life trolley-riding neighbor—and he hides that he is Jewish so that he can work in a brick factory located in a district closed to Jews. In contrast to Beilis, he is childless, a cuckold, and loathed by nearly all Gentiles he encounters. For moral and intellectual sustenance he relies on the life and thought of Baruch Spinoza, though, in this respect, he more closely resembles a figure from Isaac Bashevis Singer’s fiction than Mendel Beilis.

Everything about Malamud’s musings about Beilis upset his heirs but nothing more, it seems, than a stray comment of his, made soon after the novel’s appearance, that Beilis had “died a bitter man.” It is difficult for any reader of Beilis’ own still-riveting tale of misery to conclude otherwise. His celebrity was instantaneous, and he was promised huge sums if he traveled the United States on a lecture tour. Reclusive and exhausted by the years in prison, Beilis demurred and was then detained by the First World War. He spent time in Palestine, where his hosts were confronted with more pressing concerns than Beilis’ material support.

In 1921, Beilis settled in New York, where things worsened still. His oldest son, who had remained in Palestine, committed suicide; promises made to him in America, no doubt sincerely in 1913, had now dried up. His celebrity had waned; job offers were few and far between. Prospective employers were wary of hiring him for menial work, but he was qualified for little else. For a while he sold insurance. His memoirs, serialized first in the Yiddish press and then released as a book both in Yiddish and English, sold fairly well, but he died a poor man. Thousands attended his funeral at the Eldridge Street synagogue.

“And that is, up to now, the last chapter in the story of my sufferings” is how Beilis summed up these grim New York years. Was it really much of a leap for Malamud to conclude that he died bitter?

Strangely enough, the historian Hans Rogger was also singed by his preoccupation with Mendel Beilis. Hans, who died in 2002, was my teacher. He was a historian of great discipline and achievement, arguably the leading scholar of Russian conservatism. In the early 1960s, he signed a book contract with a large trade publisher, I think Random House, to write the definitive work on Beilis. The manuscript was nearly completed, his widow Claire recalls, on the terrible morning when the copy of Maurice Samuel’s Blood Accusation—Hans had no idea that Samuel was at work on it—appeared on their doorstep. As soon as he read it, he cancelled his contract and destroyed the manuscript. His papers, now at the Hoover Institution, offer no clue as to what the work might have looked like, though his stunning Slavic Review essay on the Beilis case, published in 1966, the same year as both Samuel’s history and Malamud’s novel, remains the finest account of its origins and implications.

There was good reason for Hans, a man of stringent standards, to despair after reading Samuel’s book. Blood Accusation is a first-rate popular history, still riveting half a century after its appearance. But Hans knew so much that Samuel didn’t, and I’ve sometimes imagined arguing with him on that awful day, trying to dissuade him from doing what he did. But I met him years later and was uneasy for the longest time in the presence of his genteel, German-Jewish urbanity. I only became his friend long after the manuscript was gone.

In Jewish Policies and Right-Wing Politics in Imperial Russia Rogger cogently explained why the Beilis affair and, more generally, the Russian-Jewish past have proven so vexingly difficult to confront with clarity:

The Russian case always seemed to be a very simple one. The existence of a Jewish problem was generally recognized, as was the fact that discrimination, openly practiced, was rooted in the laws and administrative practices of a backward polity and society.

Beilis’ tale, seemingly so transparent, but in reality so wildly complicated, provides a particularly bracing reminder in this regard. Lessons drawn from it have mostly been ill-conceived. The story of Beilis’ own life before his arrest provides little support for those inclined to conflate Russian-Jewish life at the empire’s end with the eventual horrors of Nazi Europe.

Still, those forces responsible for thrusting Beilis into the limelight, while not nearly as well organized or officially mandated as has long been assumed, were little less fierce in their loathing for Jews than those who were later at the helm of Hitler’s Europe. To be sure they did not have the same genocidal plans, but in both cases one sees a hatred numb to the mundane demands of literal truth, while confident in its capacity to understand life’s most important, terrible secrets in terms of Jewish perfidy.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

In Memory of Judah Maccabee

That Judah, the great victor of the Hanukkah story, ultimately died fighting the Seleucids is something that surprisingly few Jews know. And were the Maccabees actually underdogs?

The Kid from the Haggadah

A 1944 poem, translated by Dan Ben-Amos.

A Lone Soldier

Every year, when Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s memorial day, rolls around, the author thinks of an idealistic college student named Alex Singer who became a lone soldier in the IDF.

Businesswomen Before Bar Kokhba

Why did a Jewish woman living 30 years (around 135 C.E.) after a set of real estate contracts were executed and with no obvious connection to the named parties have them in her satchel when she fled Ein Gedi?

Mark Stein

Steven Zipperstein faults us for including, in our new edition of Mendel Beilis’ memoir, unfavorable commentary on Bernard Malamud and his novel The Fixer. At the outset, we want to stress that our main purpose in publishing Blood Libel: The Life and Memory of Mendel Beilis was not to criticize Malamud, but to put Beilis’ memoir back into print. We are gratified that Zipperstein considers the memoir a “still-riveting tale.”

That said, we do have an extended essay in the book, titled “Pulitzer Plagiarism,” in which we level a number of charges against Malamud regarding his fictionalized retelling of the Beilis story. We appear to have convinced Zipperstein of the justice of our first charge: that in writing his novel The Fixer, Malamud plagiarized from the 1926 English edition of Beilis’ memoir, The Story of My Sufferings. Zipperstein even adds an additional charge of plagiarism, saying that “Malamud lifted passages almost directly from Life Is with People, much as he did from Beilis’ memoir.” Given this acknowledgment of Malamud’s plagiarism, we are at a loss to understand why Zipperstein felt it necessary to make the sophomoric comment that “even paranoiac relatives can have genuine cause for complaint.” Since we have genuine cause for complaint, we are not paranoid.

Zipperstein writes that Malamud was “hounded by Beilis’ heirs” when The Fixer first appeared in 1966. This is a vast exaggeration. David Beilis, the son of Mendel Beilis and the father of Jay Beilis, corresponded with Malamud, sending him two letters. David Beilis also sent a letter to the editor of The New York Times Book Review, which was forwarded to Malamud, and to which Malamud responded.

David Beilis had two main concerns about The Fixer, which remain our main concerns today. First, Malamud plagiarized from Mendel Beilis’ memoir. Second, Malamud gave to his Beilis-based character, and to that character’s wife, unfavorable qualities that would predictably be imputed to Beilis and his wife .

These may seem like inconsistent criticisms, but in fact they are not inconsistent. Indisputably, Malamud’s novel has caused two kinds of confusion about Beilis. First, it has caused literary critics and other readers to give Malamud credit for inventing passages that he plagiarized. Second, it has caused literary critics and other readers to assume that the historical Mendel Beilis shared some of the unfavorable traits of Malamud’s protagonist. We document both kinds of confusion.

There has been considerable debate over whether authors of historical fiction have any responsibility to avoid debasing the reputations of real people about whom they write. We argue that the fiction author’s responsibility is at its highest when he is writing about people who have come into the public eye because they have suffered unjustly. We also argue that whatever artistic license Malamud might have possessed, he forfeited that license through his plagiarism.

Far from giving Beilis credit for the passages he borrowed, Malamud made several public statements belittling Beilis, thus adding insult to injury. Zipperstein focuses on Malamud’s remark that Beilis “died a bitter man.” Zipperstein wonders how we can possibly disagree with Malamud’s assessment, given all that Beilis suffered, including tragedies and disappointments following Beilis’ release from prison.

In addressing Malamud’s “bitter man” remark in our book, we grant that “there may be an element of truth” to what Malamud said (p. 284). We then argue, based on documentary evidence, that while Beilis had cause to be bitter at the end of his life, he was probably less bitter than others would have been in his place. Our evidence includes what is probably Beilis’ last recorded utterance, his 1934 letter to Oskar Gruzenberg, the Russian-Jewish lawyer who had been Beilis’ lead defense counsel at the trial in 1913. In this letter, written while Beilis was in failing health and close to death, he stated: “I am happy. God permitted me to live and I am able to write to you….” That does not sound very bitter to us.

By the way, in the listing for our book in this review, the author’s name “Mendel” is misspelled as “Medel.” The price listed for the book is also wrong: it is $15, not $29.95.

Jay Beilis

Jeremy Simcha Garber

Mark S. Stein

gwhepner

MEA CULPA’D

Crusades, blood libels, inquisitions and conversions that were forced,

indifference to the blood of helpless Jews spilt in the holocaust,

a litany of crimes for which the Pope should use his bully pulpit,

and yet equivocates while in denial, hardly mea culpa’d,

will be forgotten soon, because the mantra never to forget

itself will be forgotten and the crimes of Nazis will be set

aside, diminished in importance by great other acts of genocide

and claims they never happened to six million, and the Jews just lied.

[email protected]