Climate of Opinion

Last year, the British scholar Alan Johnson spoke up against a resolution to boycott Israel at the National University of Ireland, Galway. As he recounts the experience, “Anti-Israel student activists tried to break up the meeting by banging on the tables, using the Israeli flag as a toilet wipe, and screaming at me, again and again, ‘Fuck off our fucking campus you fucking Zionist!’” This outburst came from students “whose heads were filled with the common sense of intellectual circles in Europe—Zionism is racism, the Zionists ‘ethnically cleansed’ the natives from the land in 1948, Israel is an ‘Apartheid State,’ Israel is committing a slow genocide against the remaining Palestinians, and so on.” Johnson recognizes that students who recite this litany of angry accusations are “in thrall to an Anti-Zionist Ideology” that turns them into dedicated “Anti-Zionist Subjects.” Most probably know little if anything about the history of Zionism or have any first-hand experience of Israel, but this ignorance does not keep them from eagerly participating in the BDS (boycott, divestment, sanctions) movement or from putting forward resolutions such as the one to which Johnson objected. Johnson’s essay appears in Cary Nelson and Gabriel Noah Brahm’s impressively comprehensive collection The Case Against Academic Boycotts of Israel.

The students Johnson encountered in Ireland have their counterparts among students, faculty members, and community activists on college and university campuses across the United States, Canada, and various European countries. They are a diverse group, and their motives may vary, but they are linked by an ideological and political stance towards Israel fueled by what Paul Berman calls “inexhaustible sources of rancor and rage.” As the chapters of this book persuasively demonstrate, one can develop a strong case against the anti-Israel boycott proposals, but inasmuch as these proposals are fueled by overwrought and adversarial passions, rational counter-arguments are unlikely to change many minds.

Intellect, in fact, is not what is first and foremost at work here. Indignation is, and it is hard to persuade angry and indignant people to rethink their positions. How, for instance, could one hope to reason with Omar Barghouti, one of the founders of the BDS movement, who is certain that “we are witnessing the rapid demise of Zionism, and nothing can be done to save it.” He unashamedly boasts, “I, for one, support euthanasia.” Barghouti claims that some of Israel’s “racist” and “sadistic” actions against the Palestinians “are reminiscent of common Nazi practices against the Jews.” Needless to say, he offers no evidence to support these outlandish charges. Barghouti, who is pursuing an advanced degree in philosophy at Tel Aviv University, leads a movement that would boycott the very institution where he studies, a consequence that seems to trouble him not in the least.

Mark LeVine, a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine and an outspoken supporter of BDS, is hardly any more convincing. LeVine recently wrote that “There is only one criticism of Israel that is relevant: It is a state grown, funded, and feeding off the destruction of another people. It is not legitimate. It must be dismantled, the same way that the other racist, psychopathic states across the region must be dismantled. And everyone who enables it is morally complicit in its crimes.”

Academic scholars, of all people, should recognize that excoriation is not an acceptable substitute for argument, but, in fact, it pervades much of the discourse that today passes as “criticism of Israel.” In 2009, for instance, a letter was sent to President Obama accusing Israel of pursuing an “insidious policy of extermination” so merciless in its character and extent as to constitute “one of the most massive ethnocidal atrocities of modern times.” It was signed by more than 900 academics. Since then, still larger numbers of people have endorsed proposals to boycott Israeli universities, cultural events, and commercial products, including Sabra-brand hummus, which has been banned from certain American university dining halls.

What is going on? The anti-Zionism that has been emerging in recent years usually has little or nothing to do with Zionism itself. What distinguishes anti-Zionism more than anything else is the negative passions it embodies. Through the frequent repetition of a limited but emotionally charged lexicon of defamatory slogans, anti-Zionism has developed a language of its own, voicing in strongly felt terms a now-familiar litany of accusations and indictments directed at Israel. The truth-content of these charges is taken to be self-evident. Fixation, fervor, the hubris of moral certainty, and a heightened degree of self-righteous anger are enough to get many to sign on. Add the consolations of groupthink, and it is no wonder that, in his contribution, Paul Berman refers to the phenomenon less in political terms than in pathological ones, as a fevered “madness.”

Nevertheless, BDS is emphatically a movement with political goals and a reasoned strategy to meet those goals. Cary Nelson describes these in detail in his useful introduction, which offers a brief history of BDS. It began at the University of California, Berkeley in early 2002 and soon thereafter spread to Columbia, Harvard, MIT, Princeton, and elsewhere. Recognizing that academic boycotts violate the norms of academic freedom, hundreds of college and university presidents have spoken out against them, and virtually every major multidisciplinary academic organization has opposed them as well. Still, the movement maintains a good deal of momentum, and divestment drives and proposals to boycott Israeli universities are ongoing and will likely continue. Depending on which BDS spokesperson one listens to, the aims may vary somewhat, but all of them speak up for greater Palestinian rights and argue that Israeli universities somehow deny those rights. Yet any informed observer knows that Israeli universities are among the most liberal institutions in the country, that many of their faculty members and students actively advocate for a two-state solution, and that large numbers of Arabs attend these institutions. Ilan Troen’s chapter, “The Israeli–Palestinian Relationship in Higher Education: Evidence from the Field,” is particularly clarifying in this regard. Academic boycotts, divestments, and sanctions are not, in fact, likely to work in favor of the Palestinians. There is ample reason, therefore, to suspect that the movement has more ambitious goals in mind than boycotts of Israeli universities. One of its advocates says as much. As As’ad Abu Khalil writes:

The real aim of BDS is to bring down the state of Israel . . . That should be stated as an unambiguous goal. There should not be any equivocation on the subject. Justice and freedom for the Palestinians are incompatible with the existence of the state of Israel.

The political philosophy that guides such an eliminationist goal is deftly analyzed in several of this book’s most notable chapters, including those by Alan Johnson, Sabah Salih, and David Hirsch. Other chapters, by Martha Nussbaum, Russell Berman, Gabriel Noah Brahm and Asaf Romirowsky, and Emily Budick, expose the hollowness of the supporting arguments and the political bad faith of the BDS campaigns. Several other contributors—Sharon Ann Musher, Michael Bérubé, Donna Robinson Divine, Nancy Koppelman, Samuel M. Edelman, and Carol F.S. Edelman—point out the threats to academic freedom that BDS activities pose and offer revealing case studies of damage already done on certain campuses.

Cary Nelson’s dismantling of Judith Butler (“The Problem with Judith Butler: The Philosophy of the Movement to Boycott Israel”), the movement’s leading philosopher and political theorist, succeeds strikingly. His analysis of the abstract, ahistorical notion of justice on which Butler bases much of her argument for the dissolution of Israel is fully convincing. To Butler, as Nelson points out, the history of the Jewish people in the land of Israel and the land’s connection to Judaism are without meaning. She simply “eschews the Zionist linkage of nation to land” and rejects the very existence of a Jewish state, not just its policies. Adopting the moral stance of an absolutist, she insists on justice as the basis for a state’s legitimacy and finds justice only in the Palestinian cause. For her, “there is no valid case to be made for Israelis as citizens of a Jewish state.” In the rhetorical economy of her work there are no competing arguments. It is a conflict between truth and error. Positioned on the side of error, Jews, therefore, are to give up their state and submit to governance by a Palestinian majority, a prospect that the overwhelming majority of Israeli Jews are not likely to endorse. Nelson is correct to conclude, then, that Butler’s proposal for a one-state solution is “a recipe for war,” for Israelis would not stand idly by while the Jewish State disappears and they fall under the dominance of Muslim Arab rule. They would fight, an outcome that never figures into Butler’s fantasy of a non-violent route to a single state.

Is it also a recipe for or a product of anti-Semitism? The question comes up time and again in this book with respect to the whole BDS movement. Butler is Jewish, as she repeatedly avows, but that fact hardly adds validity to arguments she makes against the Jewish State or necessarily keeps her at a distance from Israel’s fiercest enemies. She is on record, for instance, affirming Hamas and Hezbollah as “progressive” movements that are to be supported as part of a global left wing, a position that most Jews would find abhorrent. Nelson claims no knowledge of what is in Butler’s heart, but his analysis of her thinking, which he finds “fundamentally flawed by its unmitigated hostility toward Israel,” leads him to conclude that the positions she argues for “have antisemitic consequences and lend support to antisemitic groups and traditions.” Kenneth Marcus devotes an entire chapter to this question (“Is BDS Anti-Semitic?”), offering a learned review of definitions of anti-Semitism, as well as several categories that are useful in thinking through the issue. He concludes that “in the last analysis, the BDS campaign is anti-Semitic.” Even if some of its proponents may hold no particular disdain for Jews, they “operate out of a climate of opinion that contains elements that are hostile to Jews.”

One wants to know more about this “climate of opinion” and, in particular, understand why certain academics are so receptive to it. Tammi Rossman-Benjamin answers these questions in her groundbreaking chapter, “Interrogating the Academic Boycotters of Israel on American Campuses,” a carefully researched, empirical study of 938 faculty members at 316 American colleges and universities who have endorsed statements calling for an academic boycott of Israeli universities.

Rossman-Benjamin’s findings are revealing: A vast majority of these scholars—789 (86 percent)—are located within the humanities (453 or 49 percent) or social sciences (336 or 37 percent). Those in engineering and the natural sciences comprise a mere 7 percent of the total (4 percent were affiliated with the arts). The departments with the largest number of boycotters are English or literature (21 percent), followed by ethnic studies (10 percent), history (7 percent), gender studies (7 percent), anthropology (6 percent), sociology (5 percent), linguistics or languages (5 percent), politics (4 percent), American studies (3 percent), and Middle Eastern or Near East studies (3 percent). Analyzing her data in order to understand the boycotters’ ideological motivation, Rossman-Benjamin discovers four recurring themes at the heart of their work: race, class, gender, and empire. Rossman-Benjamin posits that scholars invested in the study of these subjects are apt to understand human experience in terms of power relationships that divide the world into the oppressed and their oppressors. Thereafter, it is but “a short ideological leap to seeing the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in the same binary terms, casting the Palestinians as the oppressed and the Israelis as the oppressors.”

To view the Palestinian-Israeli dispute in these terms is, of course, to reduce its complexity to Manichean notions of good and evil. This is not the way one would hope that our teachers of history, literature, and society think, but, of course, Rossman-Benjamin is right that it is the kind of thinking that shapes much of the discourse of Israel’s academic boycotters. The language and the anti-Zionist politics they reflect are largely products of the ideological left, with which many of those who pursue race, class, gender, and empire studies align themselves. Within certain scholarly and intellectual circles, to be a member of the left in good standing today almost requires that one be an anti-Zionist. As Cary Nelson comments, “An overall progressive agenda cannot move forward without first dismantling the State of Israel. Anti-Zionism becomes the necessary precondition of all other progressive commitments.”

Try as they might, BDS and other campus-based anti-Israel activists will not succeed in dismantling the Jewish State, nor will the tiny minority of Israeli scholars who have emerged as boycott advocates (they deserve a study unto themselves). Their various boycott campaigns have scored no major victories to date, but by constantly maligning Israel as an unjust, racist, apartheid state, they no doubt are making the country seem sinister in the eyes of growing numbers of people. Instances of Israeli scholars being dropped from the editorial boards of certain journals or otherwise shunned are documented in this book. One also hears anecdotally of scholars who will no longer collaborate with Israeli colleagues or participate in conferences at Israeli universities. In such cases, it is more than just good professional manners that are being violated: decency is, and fairness, and personal and national dignity.

It is hard, personally and professionally, for Israelis to know how to respond to such insults. To answer indignation with indignation will not ease the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, but, then, neither will BDS and its faithful followers. What it will do is let the latter know that Israelis and their supporters will not remain passively on the receiving end of moral smugness and undeserved insults. To refuse to accept an imposed defensive crouch as one’s natural posture, as this book admirably does, also makes a case against academic boycotts of Israel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

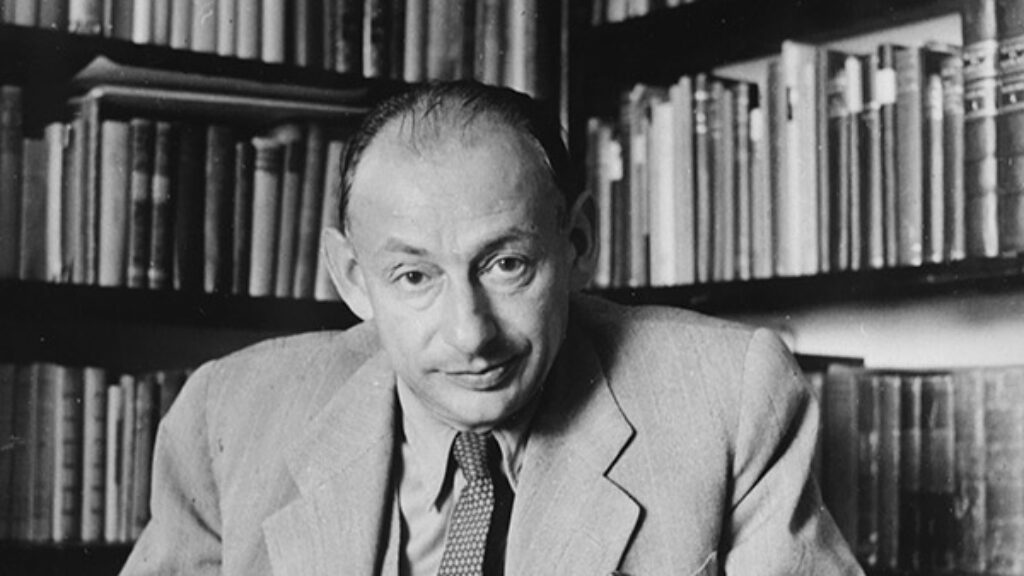

My Father, Milton Himmelfarb

Personal reflections on the legacy of a sui generis Jewish American sociographer and essayist.

Words, Words, Words

The super sad truth about Gary Shteyngart's new novel.

Between Frankfurt and Jerusalem: Scholem, Adorno, and the Fate of the Sacred

When the philosopher Theodor Adorno met Gershom Scholem, he thought that he “gave the impression of a Bedouin prince.” Their lifetime of letters orbits their shared love of their brilliant, doomed friend Walter Benjamin.

Comes the Comer

The New American Haggadah boasts a high-profile cast of contributors—Jonathan Safran Foer, Nathan Englander, Nathaniel Deutsch, Jeffrey Goldberg, Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, and Lemony Snicket. But it also features a series of unfortunate translations and commentaries.

Daniel Liechty

Clearly a major portion of the passion motivating BDS and similar initiatives is the simple frustration of having no genuinely realistic alternatives for concretely influencing Israeli policies toward the Palestinians. Instead, people are told, in effect, to ignore the situation as none of our business. Another major portion, I suggest, is the internalized guilt people feel about the fact that we too (pretty much no matter where we call home) are living on lands that were taken from indigenous native populations, by means of legal trickery, brutality, territorial cleansings, and even genocidal policies that are historically undeniable, though also mostly kept under various gradations of ongoing silence. Nothing can be done to change this history and expurgate the guilt and so, I suggest, we habitually deal with it by transforming it into righteous indignation aimed at whatever we perceive (rightly or wrongly) as analogous situations of unfair treatment of native populations in the present by others.

Daniel Liechty

Clearly a major portion of the passion motivating Americans in support of BDS and similar initiatives is the simple frustration of having no genuinely realistic alternatives for concretely influencing Israeli policies toward the Palestinians. Instead, people are told, in effect to ignore the situation as none of our business – we live here, you don’t, so you have no right to criticize or intervene. Another major portion that we hear all but nothing about, is the internalized guilt that people feel about the fact that we too (pretty much no matter where we now call home) are living on lands that were taken from indigenous native populations, by means of legal trickery, brutality, and even genocidal policies that are historically undeniable, though also mostly kept under wraps of silence. Nothing can be done to change this history, but I suggest that we habitually deal with the internalized guilt by transforming it into righteous indignation aimed at what we perceive (rightly or wrongly) as similar instances of unfair treatment of native populations in the present.