Jews of Dune

Frank Herbert’s Dune, often named as the greatest science fiction novel ever written, turns 50 this year. Set thousands of years in the future, the novel and its sequels portray a universe in which religion is a powerful influence, yet in which the religions of our own time—Christianity, Islam, Buddhism—are scrambled, changed at times almost beyond recognition. Much of humanity follows a religion called Zensunni, for instance, one of several syncretic belief systems through which Herbert winks at the reader, who sees how the supposedly timeless faiths and scriptures of today will be altered and recombined for use tomorrow.

Indeed, Herbert’s fictional universe juxtaposes religion, which is presented as mutable and manipulable, with genetics, in which the permanent truths reside. This is seen especially in the operations of the Bene Gesserit, an all-female organization that controls the destiny of humanity. For thousands of years they have secretly stewarded the genetic lines of humanity, with the ultimate goal of engineering a messiah. In the meantime, they create and exploit religion to control and guide human populations. “We plant protective religions to help us,” explains a member of the order. “That is the Missionaria’s function.” We “[e]ngineer religions for specific purposes and selected populations,” says another. The religions of Dune are fungible covers for foundational truths that are locked in genetic memory.

Only one religious group from our own time has defied this garbling of dogma and practice. In Chapterhouse: Dune, the sixth book in the series and the last Herbert wrote before his death in 1986, the Jews show up. And, unlike other faiths, the Judaism of the far future has changed not a whit. “It is probable that a rabbi from ancient times,” explains a Bene Gesserit leader to her disciple, “would not find himself out of place behind the Sabbath menorah of a Jewish household in your age.” Against a backdrop of transformed humanity, mutated space navigators, and shapeshifting “face dancers,” Herbert’s Jews are as they have always been.

Demonstrating absolute fidelity to their “old religion,” the Jews of Dune are concerned mainly with their own survival. They must cultivate extreme secrecy because their separatist ways elicit ongoing anti-Jewish violence. The leader of the Bene Gesserit explains:

They made a defensive decision eons ago. The solution to recurrent pogroms was to vanish from public view. Space travel made this not only possible but attractive. They hid on countless planets—their own Scattering—and they probably have planets where only their people live . . . [T]heir secrecy is such that you could work a lifetime beside a Jew and never suspect.

This secrecy allows the group of Jews who appear in the sixth book to assist the Bene Gesserit. One of the Jews, Rebecca, even joins the female order, to the dismay of the rabbi who leads their little flock.

Herbert’s portrait of the Jews owes more than a little to anti-Semitic stereotypes. The Jews of Dune, with the exception of Rebecca (perhaps a nod to the noble Jewess of that name in Ivanhoe) are insular, xenophobic, and fanatical. The rabbi is a whiny, bullying, pathetic figure who wails when his orders are countermanded and waves some kind of Jewish scroll for emphasis when he speaks. The Jewish plotline echoes Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, as Rebecca, like Shylock’s daughter who steals her father’s treasure and elopes with her Christian lover, similarly defies the rabbi and takes what she calls her “golden egg” (in this case not real gold but a trove of portable genetic memories) to the Bene Gesserit. When Rebecca joins the order, she quickly realizes that Judaism “required [her] to believe so many things she now knew were nonsense” and she characterizes it as a product of “[m]yths” and “childish behavior.” There is even a possible hint of the charge of deicide, when one of the rabbi’s disciples says cryptically: “our ancestors did things for which payment must be made.” By contrast, the only possibly positive Jewish note in the series is the fact that Herbert’s term for his Dune messiah—the Kwisatz Haderach—resembles the Hebrew phrase kefitzat haderech, a magical transport or teleportation (which is how Emanuel Lotem renders the term in his 1989 Hebrew translation of Dune).

Why this eruption of hoary anti-Jewish stereotypes in a futuristic epic? It seems to derive not from contempt for the Jews, but from Herbert’s envy of them. On the one hand, Herbert’s portrayal of the Jews as an unchanging relic, the only stagnant group in a universe of change, is an old trope, given repeated modern expression from Hegel to Toynbee and reflecting supersessionist Christian claims that the Jews have had their day but are no longer a living part of history’s drama.

But the flip side of this denigration of the Jews as a “fossil-people” is a Christian anxiety that the Jews—who claim biological kinship with the patriarchs, prophets, and messiah—naturally possess that with which Christians have a more uncertain relationship. Herbert’s Dune novels are all animated by the conviction that the truth is in our genes. The problem Jews pose for Hebert, then, is not that they are unnecessary to his fictional universe, but that they appear to anticipate it because of their familial, corporeal relationship with the divine. At one point, a Bene Gesserit member remarks: “Jews are amused and sometimes dismayed at what they interpret as our copying them. Our breeding records dominated by the female line to control the mating pattern are seen as Jewish.” There appears to be a kind of theological resentment at work.

While other science fiction writers such as Dan Simmons and Joel Rosenberg have portrayed futuristic Jews more positively, Herbert’s treatment recalls another science fiction classic, Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s post-apocalyptic novel A Canticle for Leibowitz. Miller recounts the Catholic Church’s efforts to reconstruct civilization after atomic war, but his tale includes a mysteriously eternal Wandering Jew who pops up every few generations to make ironic commentary upon Church’s efforts. While the nastiness of Herbert’s Chapterhouse is absent in Miller’s case, the message is similar: Christians have to piece together the fragments of civilization, which changes over time; Jews, in part because of their stony inability to change, can just remember it all.

As it happens, most readers lose interest before they reach the sixth book in the Dune series. While Dune remains a bestselling mainstay of the science fiction canon, the quality of writing deteriorates in the sequels and the plots start to repeat themselves. (In fact, several of the main characters in the later books are literal clones of characters from the first.) The first book did spawn several screen adaptations, including a 1984 film by David Lynch and a TV miniseries in 2000, while a recent documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), recounts the attempt of the Chilean born filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky to direct a film version of the book in the 1970s. It becomes evident early on in the documentary that Jodorowsky, like most of the people he enlisted in his project (including Salvador Dali and Mick Jagger), was only minimally acquainted with Herbert’s novel. The documentary is a very funny chronicle of the director’s surprisingly winsome megalomania and New Age spiritual pretentions. We learn that his tome of storyboards would have resulted in a 14-hour-long movie only tenuously related to the book. In the end, he managed to spend several millions of investors’ dollars on a film that was never made. One might have forgiven Herbert, and had a more interesting portrayal in hand, had he based any of his Jewish characters on the feckless (and Jewish) dreamer Jodorowsky.

Because Herbert died soon after the publication of Chapterhouse: Dune, we cannot know precisely how he intended to conclude his saga—despite a pair of sequels written two decades later by his son, both based on a sketchy plot outline discovered among Herbert’s effects. Chapterhouse: Dune ends with the rabbi, Rebecca, and their fellow Jews accompanying a group of Bene Gesserit members on a lone spaceship, bearing as its cargo the genetic information needed to re-clone the messiah. One presumes, given their fierce traditionalism, that on their long journey they will continue to light their “Sabbath menorahs” once a week and look forward to celebrating Passover in Jerusalem with their messiah, who perhaps they can clone next year.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Sometimes a Bag Is Just a Bag

Daphne Merkin's new collection is signature Merkin: funny, smartly written, and utterly self-indulgent.

The Quality of Rachmones

Howard Jacobson's Shylock Is My Name is dead serious and very funny, high criticism and low comedy.

No Tips

Yale's Jewish Lives Series finds an unlikely subject: Leon Trotsky.

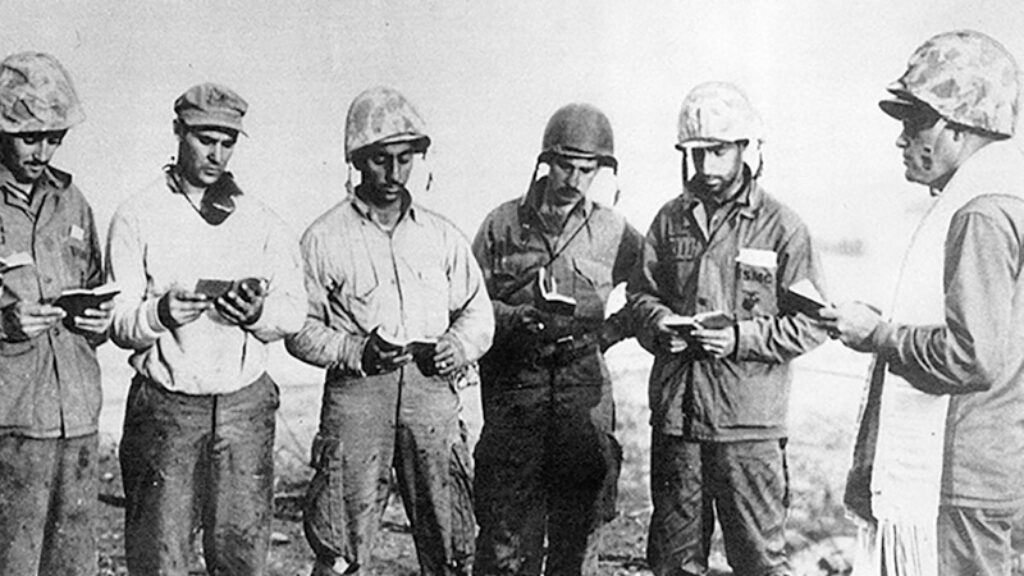

This Shall Not Be in Vain

Rabbi Roland B. Gitelsohn was a pacifist when World War II started. Four years later he was chaplain at the Battle of Iwo Jima. His long-lost memoir has just been published.

Lincoln Anderson

Thanks for this article. I'm a huge Frank Herbert fan, and really admire his intelligence and writing style and the world he creates. But I was a bit weirded out by the ending of "Chapterhouse Dune" when I read it years ago. It did seem to be a very negative portrayal of Jews. He is Catholic, maybe he had a strong faith, perhaps that was partly behind it? I have read a lot of his stuff, and feel I may have picked up a similar vibe re Jews in one or two other places in his books and stories. It's strange that he had such a great mind and was such an amazing writer -- style-wise, I love his language, pacing, his sort of vague detail≤, which allows the mind to fill in the picture and imagine, which is what reading is really about. And yet, he had that quirky aspect, which drops him down a few notches or more in my view. It's sad that, for a smart guy, he didn't have a more sophisticated view of Judaism.

[email protected]

While able to deal with fascinating concepts the author's portrayal of the Judaism of the far future disappoints in adding few insights and no understanding of the nature of this fascinating part of humanity.