Strange Journey: A Response to Shmuel Trigano

In his “Journey Through French Anti-Semitism” (Spring 2015), Shmuel Trigano paints a sobering portrait. According to his account, France has been careening toward an anti-Semitic crisis for some 30 years—an historical evolution he attributes to the French left in the 1980s and the traditional teachings of Islam. The author claims, moreover, that his own experience has repeatedly confirmed the indifference of the French state and much of French society toward rising anti-Semitism. France, he argues, is far too uncritical of Islam and Muslims; the future for French Jews looks decidedly bleak.

We do not wish to trivialize Professor Trigano’s personal experiences. Moreover, we share his concerns about the recent history of Jews and of Muslim-Jewish encounters in France. The taking hostage and murder of Jews in January 2015 at the Hypercacher supermarket in Paris was a horrific act of anti-Semitism. Professor Trigano is correct that this attack was hardly an isolated event: Since autumn 2000, France has seen a major spike in anti-Semitism, in which physical attacks against Jews and Jewish institutions have played an increasingly lethal role. Moreover, recent opinion surveys indicate a significant percentage of the French public, Muslims especially, harbor negative stereotypes about Jews. We also view with serious concern the rise of pockets of radical Islam in France and agree that moderate Islamic leaders should exert a more systematic effort to shape attitudes among French Muslims on a number of important issues. Likewise, we concur that the far right has played a key role in setting the terms of contemporary French politics and has shown repeated ambivalence regarding questions of anti-Semitism.

While we thus agree with Professor Trigano on several points, his overall analysis profoundly distorts recent Muslim and Jewish history in France. Indeed, he makes a number of problematic historical leaps and unsubstantiated claims. First, his focus on developments of the 1980s as the causal framework for understanding anti-Jewish violence in recent years places undue emphasis on a particular moment of French history without accounting for subsequent transformations. He also makes assertions about the 1980s itself that are incomplete and misleading.

For Trigano, the origins of many of France’s recent problems can be found in the period following the influx of North African and Sub-Saharan African immigrants into France and the 1981 election of François Mitterrand’s Socialist Party. In Trigano’s telling, as immigration became increasingly controversial, Mitterrand and his party fought the growing influence of the far right under Jean-Marie Le Pen by establishing an “anti-fascist front” that incorporated the fight against anti-Semitism to prove the justness of its cause. Trigano focuses particularly on the founding of SOS Racisme, a Socialist-backed anti-racist body that he argues conflated Jews and immigrants into a single construct to fight for a more just France. This move, he insists, positioned Jews outside the national community by linking French Jewish citizens with Muslim immigrants, a construct from which he maintains French Jews have never emerged.

There are numerous problems with this analysis. Certainly the founding of SOS Racisme marked a dramatic turning point in Muslim-Jewish cooperation in France thanks to the joint efforts of the French Jewish Students’ Union (UEJF) and numerous prominent “Beur” activists (“beur” being the popular slang term for French-born Muslim citizens of immigrant parents). Working together to create a just and peaceful France, these activists put aside their differences—which emerged most often around the Israeli-Arab conflict—in order to combat racism. But Professor Trigano’s claim that SOS Racisme’s most significant slogan was “Jews=Immigrants” is simply untrue. In fact, SOS Racisme became most widely known for its hand-shaped yellow badge that read “Touche pas à mon pote” (Hands off my friend). And while the term “pote” consciously sought to blur immigrant and native, outsider and insider, to communicate that all victims of racism were the same, the Beur activists who helped build this organization were generally not immigrants; rather, they were French-born Muslim citizens with as much a claim to national inclusion as their Jewish allies. If activists in SOS Racisme argued that anti-immigrant racism and anti-Jewish racism were equally dangerous, the essential basis for their partnership was their joint citizenship, not foreignness.

Moreover, while SOS Racisme was arguably as influential as Professor Trigano suggests in its early years, by the end of the 1980s the organization had been weakened dramatically due to three factors: the First Intifada that brought divisions over the Middle East conflict to the fore; the rising electoral strength of the National Front and the impact of its anti-immigrant rhetoric; and the first headscarf controversy in 1989, which focused attention on Muslim religious difference. Under these circumstances, Muslim activists started to stress the deep structural biases against Muslims, while Jewish activists began to emphasize Jews’ long history in France and the ease of their integration compared to Muslims. In relatively short order, then, the alliances forged in the early 1980s broke down with few of the enduring legacies that Trigano claims. Indeed, his analysis ignores such critical developments as the refashioning of national political culture by subsequent regimes, decades of structural inequities for French Muslims, and the rise of global Islamic fundamentalism over the last 15 years. Likewise, his assertion that the government repeatedly refused to acknowledge the seriousness of anti-Semitism in France overlooks considerable evidence to the contrary. While such a critique was warranted in the early 2000s, since 2003, three successive French heads of state have repeatedly condemned both individual anti-Semitic acts and the broader presence of anti-Semitism in no uncertain terms. Moreover, in annually published government reports, the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights has painstakingly documented the number of anti-Semitic incidents in France and the degree to which they dwarf those of racist crimes against any other group.

Even more problematic is Professor Trigano’s repeated insistence on the “automatic exculpation of Islam from any responsibility.” In fact, for at least half a century, various state and non-state actors have presented Islam and Muslims as a central problem facing French society. The 1989 head-scarf affair moved rapidly from a local dispute into a national cause célèbre, the stakes of which were described repeatedly in apocalyptic terms (several prominent intellectuals, for instance, warned ominously that this could mark the surrender of secular public education in France). Debates over the hijab only resolved in 2004, after the president of France convened a national commission on the issue of “ostentatious religious signs” in schools. Numerous scholars such as John Bowen and Joan Scott have convincingly shown that such high-level attention had little to do with a real crisis for schools or secularism and everything to do with fear and demonization of Islam. In 2008, then-President Nicolas Sarkozy successfully pushed for the passage of a national law banning the niqab, or so-called burqa, a more restrictive garment worn by perhaps a few thousand Muslim women in all of France. Two years later, facing growing unpopularity, Sarkozy’s government convened a months-long national debate—scheduled to conclude on the eve of the regional elections—about the meaning of French identity, insisting that the burqa, deemed once more a major national issue, be an item for discussion. Professor Trigano’s piece fails to acknowledge this unmistakable historical pattern of Islam and Muslims being anything but exculpated by the French state and society.

Indeed, Professor Trigano is himself quick to criticize Islam as a whole. When he claims that “there is a long history of Islamic anti-Judaism, and it is the reason for the attacks against the Jews,” the author falls into a vision of Islam as characterized from the Qur’an to the present by an unceasing, immutable hatred of Jews. As numerous scholars such as Mark Cohen have documented, the pre-modern history of anti-Judaism was far more severe and persistent in Christian Europe than in the Islamic world. No serious student of Islamic extremism today, no matter how critical, would claim that jihadists such as the Kouachi brothers, Amedy Coulibaly, or Mohamed Merah (the assailant in the 2012 shooting at a Jewish school in Toulouse) have simply followed Islam’s traditional teachings regarding Jews. Rather, numerous analysts have shown how the leading ideologies of radical Sunni Islam like Salafism and Wahhabism—which emphasize lethal hatred of Jews, Christians, and the West—are distinctly modern. Such extremists draw selectively on texts like the Qur’an to justify what are in fact radical departures from mainstream tradition. Clearly, the attack at Hypercacher is no more a simple outgrowth of what Professor Trigano calls “the traditional Muslim disparagement of non-Muslims” than was Baruch Goldstein’s Purim massacre of 1994 in a mosque at the Cave of the Patriarchs the logical outcome of the ancient Jewish injunction to destroy Amalek and his descendants.

Professor Trigano’s article also equates Muslims with foreigners. As noted above, his critique of the Mitterrand government in the 1980s contrasts Muslims as “newly arrived immigrants” with Jews, whom he insists should never have been identified as a “community of immigration.” Such a distinction belies the complexity of the recent history of Muslims and Jews in France. France’s Jewish population more than doubled in the mid-to-late 20th century due to a large migration wave from North Africa that included Professor Trigano himself. While the Algerian Jews who made up one half of this migration were technically “French,” so too were Algerian Muslims, who had held French citizenship since 1946.

Indeed, the author’s invocations of the history of French Algeria and subsequent post-colonial migrations are decidedly problematic. While we do not doubt his painful memories of his family’s departure from Algeria in 1962, when he claims “The State had abandoned us; death loomed,” he distorts history. As Todd Shepard demonstrates in his recent book, The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France, if any group should have felt abandoned in 1962, it was Algeria’s Muslims. By the time most Jews left Algeria, key Jewish and non-Jewish actors had successfully ensured that they would be able to retain their French citizenship and be classified, like the French colonists in Algeria, as “Europeans.” A spring 1962 law provided for significant material aid and basic support for all immigrants in this category upon their arrival in France.

Muslims in Algeria, meanwhile, generally lost their French citizenship at the very same moment; the vast majority of these French citizens were explicitly not classified as “Europeans.” Moreover, the so-called harkis, the Muslim soldiers who had fought on the French side during the struggle for Algerian independence, were indeed abandoned by the French state. At least 10,000 were massacred by the Algerian nationalists while the French military—under secret orders from President Charles de Gaulle—refused to help them escape to France. Muslim soldiers who did eventually migrate to France were typically housed for decades on the fringes of society, in the sub-standard living conditions of French camps, foresting villages, or specially built urban housing. Although Professor Trigano’s insistence on recurrent Jewish abandonment by the French state suggests that Jews were uniquely targeted, in fact the story is far more complex.

This brings us to another key difference in the positions of Jews and Muslims in French history and society. As we have acknowledged, anti-Jewish attitudes and violence are certainly on the rise in France. However, racism, as is well-known, must be measured by an additional dimension: the structural limitations that prevent full participation in a given society. In the French case, there are few, if any, structural barriers facing France’s Jewish citizens. With full access to jobs, housing, education, and the range of life opportunities, French Jews enjoy an arguably unprecedented level of acceptance. By contrast, as numerous sociological studies about employment, housing, police practices, and more have shown, it is Muslims in France who face the greatest structural barriers. To speak merely of rising anti-Semitism in a context in which other French citizens are being systematically targeted for discrimination is, then, to present a skewed picture of the nature of bigotry in contemporary France.

Clearly, French society has arrived at an extremely challenging moment in its relationship to its Jewish minority. And unlike Professor Trigano, we have the luxury of writing from the other side of the Atlantic, which means we do not experience the daily tensions in France as he does. Yet we remain deeply concerned about the distorted view of French society to which his essay gives expression. Professor Trigano’s attacks on left-wing multiculturalism, on expressions of public difference, on allegedly widespread indulgence of Muslims, and on Islam itself add up to a rejection of any possibility that France might come to embrace its multi-ethnic reality in an inclusive manner. If such views become dominant, the future of Jews in France is indeed bleak.

Shmuel Trigano’s original article on French anti-Semitism can be found here.

Trigano’s response to Katz and Mandel can be found here.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Our Master, May He Live

Rashi's commentary on the Chumash isn't just about textual puzzles, it's about God's love for the Jewish people. So argues Avraham Grossman in a new biography.

We Agree on Herzl

You know a review has turned mean-spirited when you’re indicted for crimes you quite carefully didn’t commit.

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

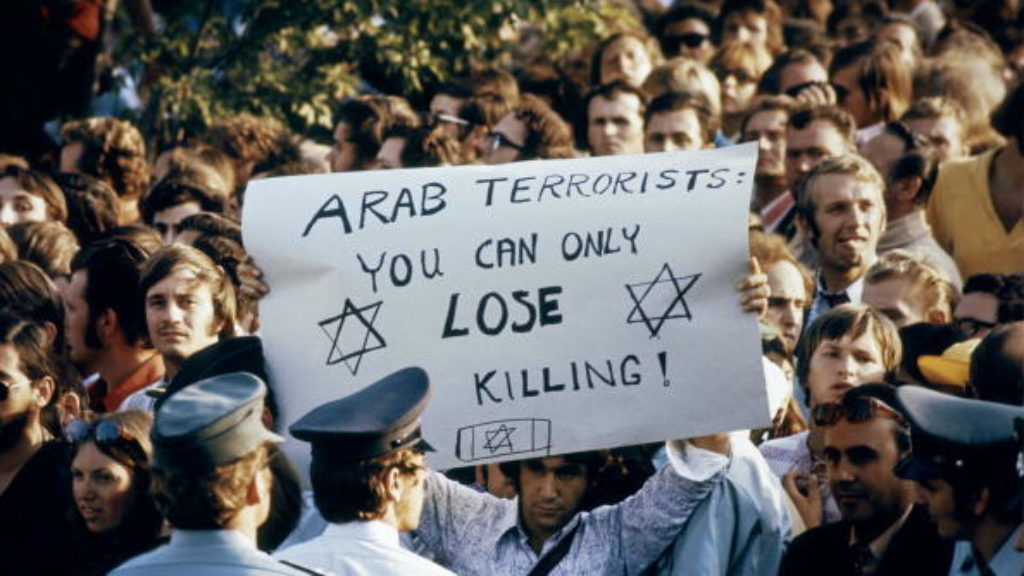

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

marhevka

Thoughtful and convincing. But please correct the misuse of the verb "belies."

daized79

I am disheartened that even in the name of "hearing all sides," JROB would publish this biased rant of a critique. Surely someone could have critiqued Trigano's piece with a more neutral viewpoint. Just some examples:

"[T]he author falls into a vision of Islam as characterized from the Qur’an to the present by an unceasing, immutable hatred of Jews. As numerous scholars such as Mark Cohen have documented, the pre-modern history of anti-Judaism was far more severe and persistent in Christian Europe than in the Islamic world. No serious student of Islamic extremism today, no matter how critical, would claim that jihadists . . . have simply followed Islam’s traditional teachings regarding Jews. Rather, numerous analysts have shown how the leading ideologies . . . which emphasize lethal hatred of Jews . . . are distinctly modern. Such extremists draw selectively on texts like the Qur’an to justify what are in fact radical departures from mainstream tradition. Clearly, the attack at Hypercacher is no more a simple outgrowth of what Professor Trigano calls “the traditional Muslim disparagement of non-Muslims” than was Baruch Goldstein’s Purim massacre of 1994 in a mosque at the Cave of the Patriarchs the logical outcome of the ancient Jewish injunction to destroy Amalek and his descendants."

Wow. First of all, the author said no such thing. Nobody claims Muslim antisemitism is "immutable." That said, it has always existed. The authors of this piece tellingly speak of "emphasis" on "lethal hatred" being modern. Perhaps. Perhaps before the "lethal hatred" was not emphasized over other religious obligation and perhaps before the "emphasis" had been on non-lethal hatred. In fact, I would agree both of those are true. But what a mealy-mouthed way of trying to discredit Trigano and praise Islam. Added together with antisemitism being worse in the Christian world and we are left indeed with high praise of this most tolerant religion. So basically if you don't torture and kill Jews as often as the Christians or don't discriminatorily tax them wuite as heavily or don't deprive them of quite as many civil rights, then you're not antisemitic? And certainly not lethally so?

It is hard to claim that modern emphasis on lethal hatred of Jews is indeed a break from mainstream tradition when that mainstream tradition had only dealt with Jews as powerless dhimmi. Certainly Mohammed emphasized a lethal hatred of the Jews who had the power to stand up to him in Arabia. The point is that the rise of the Jews in Israel, a previously Muslims land, is something new for Islam to encounter and, relying on that "mainstream tradition," Islam does not generally have good or neutral reaction. In that sense, ironically, some of the antisemitism is indeed caused by Zionism, but only because the Jews are not supposed to have power or self-determination. And if you think that's an okay response, just go hang yourself and get it over with. But again, it is only the emphasis on the lethal hatred--the hatred has always been there as has the episodic lethality.

And Baruch Goldstein and Amalek? Really? First of all, there is NO Jewish movement that thinks gunning down innocent Muslims is okay. NONE. I don't know what Goldstein thought or didn't think he was doing, but if I had to guess, he thought he was taking revenge for Jewish life (if you need a biblical source for your analogy, how about Reuben and Simon at Shechem?). But second and more importantly, you are once again (the first time was comparing Islam to Christianity) trying to praise and defend Islam by saying see these people are as bad or worse! This is a common (in every sense of the word) and intellectually bankrupt tactic from the Left and has no place in the pages of this magazine.

"Professor Trigano’s article also equates Muslims with foreigners. As noted above, his critique of the Mitterrand government in the 1980s contrasts Muslims as “newly arrived immigrants” with Jews, whom he insists should never have been identified as a “community of immigration.” Such a distinction belies the complexity of the recent history of Muslims and Jews in France. France’s Jewish population more than doubled in the mid-to-late 20th century due to a large migration wave from North Africa that included Professor Trigano himself. While the Algerian Jews who made up one half of this migration were technically “French,” so too were Algerian Muslims, who had held French citizenship since 1946."

France's Jewish population doubled only because France had partnered up with Germany in exterminating a quarter of its Jews a decade earlier. I understand the unease at which a Jew says, "I got here first so I'm not an immigrant but you Griener are." But of course in reality the Jews have been in France since the 5th Century at least, the Muslims didn't exist then. France and Jews have been intertwined for over 1,500 years, and have had cultural influence on each other in a way that France has not with the Arabs and Islam have not. That is not to say there has been none--the French wars with the Muslims in the Middle Ages certainly led to cross-cultural influence. But not of the same depth and caliber. The French Jews, at least since the founding of the Republic, have always considered themselves very "French" and comported themselves accordingly. Has this been true of Muslim immigrants? Especially actually religious Muslim immigrants?

More specifically, you make the assertion that Algeria's Muslims were French citizens since 1949 while Trigano made the assertion that Algeria's Jews had been French citizens since 1870. I don't know which is true or what citizenship meant (that is, it seems, the supposed area of the authors' expertise), but there is a huge difference between 1870 and 1949--and not just in number of years but in eras, one is before WWI and one is after WWII. The political and cultural changes globally and in France are too great to mention.

After hearing about the harkis, one thing we can all agree on is that France is a "sh**** little country."