On Old Stones, a Black Cat, and a New Zion

There is a legend that explains the curious name of Prague’s Altneuschul (Old-New Synagogue). The foundations of the new synagogue were laid with old stones from the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, but that is only part of the explanation. The Jews had carried these stones into exile on their backs, or perhaps angels had transported them. Moreover, Altneu can also be traced to the phonetically close Hebrew term al tenai, meaning “on condition.” Whether it was angels or exiles, the condition in question is that the Jews of Prague promised to return the stones, soaked with the blood of martyrs, to the Holy Land upon the messianic rebuilding of the Temple.

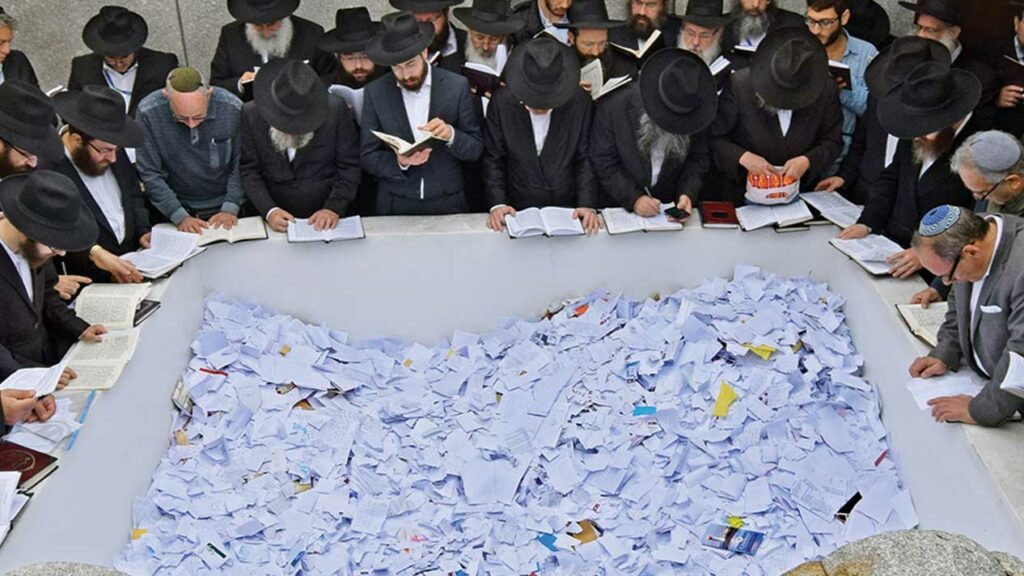

Of course, the legend everyone knows about the Altneuschul is that its greatest leader, Rabbi Judah Loew, known as the Maharal of Prague, created a golem to protect the city’s Jews from destruction sometime in the 16th century. When he lost control of his creation, the Maharal managed to remove the slip of paper with God’s name that had brought it to life, and the creature collapsed into the clay from which it had been fashioned. The clay corpse was then stored in the synagogue’s attic, in case the Jews of Prague ever needed its protection again. The Altneuschul was already three centuries old when the Maharal arrived on the historical scene, and at least two hundred years older than that by the time the Golem of Prague story was first told. The story, as many scholars have shown, has more to do with 19th-century notions than it ever did with the Maharal’s practical Kabbalah.

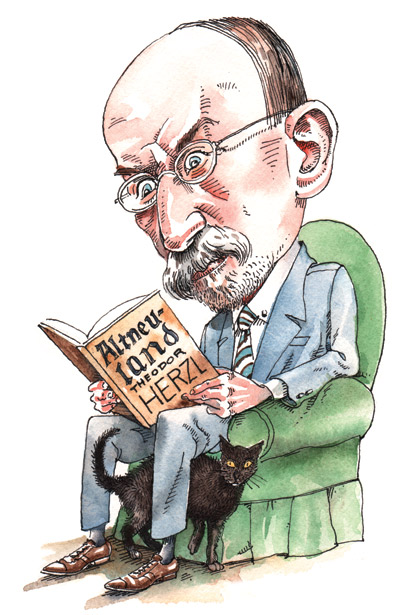

As is well known, Herzl took the inspiration for the title of his 1902 utopian novel Altneuland (Old-New Land) from the name of the great Prague synagogue, which Herzl had visited as early as 1885. On August 30, 1899, he wrote in his diary that the epiphany of his “Zion novel” and its name came to him during a bumpy bus ride. Altneuland alluded to the Altneuschul: “It will become a famous word.” Most commentators take this choice of title as symbolic of how Jewish continuity in Europe will be politically transposed onto the new terrain of Palestine. Georges Yitshak Weisz, in his Theodor Herzl: A New Reading, is one of the few commentators to have connected the novel with another, even more obscure legend of Prague, magic, and the Altneuschul that Herzl himself found strangely intriguing.

The novel has never been plausibly read as a literary achievement, but it did work out several fundamental aspects of Herzl’s liberal political vision that had received scant attention, or none at all, in his watershed 1896 pamphlet Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State). Herzl’s great rival Ahad Ha-Am greeted his novel with blistering criticism: Herzl’s universalist pretensions and Jewish ignorance precluded a truly Jewish vision. Herzl, he argued, imagined a European cookie-cutter state rather than accepting the challenge of developing a vision from within Jewish tradition and experience. Ahad Ha-Am’s polemic and the counter-polemics of Max Nordau and others roiled the Zionist movement for months. This is an argument, about both Herzl and Zionism, that has yet to be resolved.

Two years before his diary entry about the Altneuschul and Altneuland, Herzl recorded a colorful legend of the Prague synagogue told to him by Eduard Bacher, his editor at the Viennese paper the Neue Freie Presse. Bacher and Herzl had a deeply ambivalent relationship. In March of 1897, upon leaving the offices of the newspaper together, Bacher showed a fleeting interest in joining Herzl on his planned tour of Palestine, which was being arranged by the Maccabean Club. Herzl showed him the organization’s travel prospectus and in turn Bacher told him a story he recalled from his youth in Bohemia. Here is the version Herzl recorded in his diary:

A Jewish woman was once sitting in her room and looking out the window. She noticed on the opposite roof a black cat in labor. She went over, took the cat, and helped her to give birth. Then she made a bed of straw on top of the coal bin for the cat and her kittens. A few days later the cat, which had recovered, disappeared. But the lumps of coal on top of which she had lain turned into pure gold. The woman showed them to her husband, and he said that the cat was sent by God. So he used the gold to build a synagogue, the Altneuschul. This is how that famous edifice came into being. But the man was left with one wish: as a pious Jew he would have liked to die in Jerusalem. He also wished he could see the cat again, for he wanted to thank her for their prosperity. And one day the woman was again looking out the window and saw the cat in its old place. She quickly called her husband saying: “Look, there sits our cat again!” The man ran out to get the cat, but it jumped away and disappeared into the Altneuschul. The man hurried after it and suddenly saw it vanish through the floor. There was an opening there, as though to a cellar. Without a moment’s hesitation the man climbed down and found himself in a long passage. The cat enticed him on and on, until finally he saw daylight ahead again. But when he emerged, he was in a strange place, and the people told him he was in Jerusalem. On hearing this he died of joy.

Black cats, the magical transformation of coal into gold, and astonishing rewards for kindness rendered are, of course, the stuff of legend, but the most salient feature of this story for Herzl, or at least for Bacher, was the synagogue’s secret portal leading directly to Jerusalem. Within the Jewish imagination, one is reminded—though Herzl apparently was not—of the Yiddish folktale Agnon would later recast in his “Fable of the Goat.” There, a boy follows a magical goat straight from the shtetl to the Promised Land.

In his diary, Herzl didn’t offer an analysis of the legend in his own name, but he did attribute one to Bacher:

The story, according to Bacher, shows how national consciousness has been preserved within the Jews in all places and at all times. Actually, he said, it lies beneath the level of consciousness and flickers through [Bacher] himself. And he said he had told me the story because he, too, had discovered within himself a desire to go to Palestine.

Herzl expresses his pleasant surprise at Bacher’s recognition of Jewish national consciousness: “What a transformation in one year!” Typically, Herzl drew the most optimistic conclusion possible from this: “I believe it is only a matter of months before the NFP [the Neue Freie Presse] turns Zionist.” It didn’t happen, nor did Bacher join Herzl on the trip, but his tale of a portal leading directly from the Altneuschul to Jerusalem seems to have taken root in Herzl’s own national consciousness. Would Ahad Ha-Am have been more receptive to Altneuland had he known that the novel, or at least its title, had its origin in a Jewish legend, however spurious? Probably not. In any case, neither Herzl’s Zionism nor Ahad Ha-Am’s was quite the same as that of the old man of the story who dies of joy upon learning that he has emerged in Jerusalem.

Suggested Reading

Ba’al Teshuvah Poetics

Part of being a ba’al teshuvah is the yearning to stop being one—to finally blend with those who never had to return because they never left.

Saladin, a Knight, and a Jew Walk Onto a Stage

Outside of Germany, Nathan the Wise is one of those works more often read than performed, and more often read about than actually read.

The Modern Crisis of Moral Thought: An Exchange

Abraham Socher's pre-Yom Kippur assessment of the possibility of true repentance led to a discussion on the mussarist's answer (or non-answer) on moral choices.

Psychology at Nuremberg

Both Kelley and Gilbert believed they could make a broad psychosocial argument despite the limited sample size, inconclusive tests, infighting, and lack of clear standards and definitions.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In