Passover on the Potomac

If the Obamas conduct a seder again this Passover, the haggadah in the hands of family members and guests-Jewish and non-Jewish-will probably be the one they have used for the past two years, that most American of haggadot, the “traditional Maxwell House.” Maxwell House was not the first company to use a complimentary haggadah to sell groceries, but it has been the most prolific, publishing more than 50 million copies since 1934. It is no surprise, then, to see it become a fixture of “our nation’s seder.”

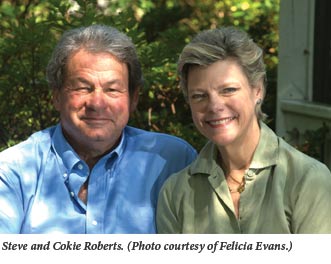

Just across the Potomac in Bethesda, Washington insiders Cokie and Steve Roberts, bestselling authors, celebrities of TV, radio and print journalism, have been holding a Maxwell House-free seder for nearly four decades. The Robertses-he’s a cultural Jew and she’s a religious Catholic-will use their homemade text, just published as Our Haggadah: Uniting Traditions for Interfaith Families and so will their kin and guests. Their roster of seder regulars recalls Adam Sandler’s “Chanukah Song”: there’s “Lesley Stahl, a Jew from Massachusetts, and her husband, Aaron Latham, a Protestant from Texas”; there’s “Linda Wertheimer (Protestant, New Mexico) and her husband, Fred (Jewish, Brooklyn), and Nina Totenberg (Jewish, Massachusetts) and her husband, Floyd Haskell (Protestant, Colorado).”

The Robertses’ initiative is a lineal descendant of the once famous and singularly high-powered seder presided over by former Secretary of Labor, Supreme Court Justice, and Ambassador to the UN Arthur J. Goldberg and his wife, Dorothy. In 1961, the Goldbergs’ guest list included President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy, the Speaker of the House, two Supreme Court justices, two senators, and the president of the AFL-CIO. In 1967, it included the newlywed Robertses, at whose wedding Goldberg had given a speech. The Goldbergs’ homemade haggadah presented Passover’s theme of freedom in American language: “The Festival of Pesach calls upon us to put an end to all slavery . . . Pesach calls us to the eternal pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Mrs. Goldberg, in her marginal notes, reminded herself to mention that “one of the best descriptions of the exodus is the great Negro spiritual ‘Go Down Moses.'” Cokie Roberts remembers participating “with gusto” when “the crowd started singing freedom songs from the civil rights and labor movements, held over from the days when Goldberg had been a leading labor lawyer.”

The Robertses’ initiative is a lineal descendant of the once famous and singularly high-powered seder presided over by former Secretary of Labor, Supreme Court Justice, and Ambassador to the UN Arthur J. Goldberg and his wife, Dorothy. In 1961, the Goldbergs’ guest list included President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy, the Speaker of the House, two Supreme Court justices, two senators, and the president of the AFL-CIO. In 1967, it included the newlywed Robertses, at whose wedding Goldberg had given a speech. The Goldbergs’ homemade haggadah presented Passover’s theme of freedom in American language: “The Festival of Pesach calls upon us to put an end to all slavery . . . Pesach calls us to the eternal pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Mrs. Goldberg, in her marginal notes, reminded herself to mention that “one of the best descriptions of the exodus is the great Negro spiritual ‘Go Down Moses.'” Cokie Roberts remembers participating “with gusto” when “the crowd started singing freedom songs from the civil rights and labor movements, held over from the days when Goldberg had been a leading labor lawyer.”

In 1968, the Robertses were on their own and tried the Maxwell House haggadah, but they ditched it the following year for their own stitched-together, pick-and-choose haggadah, modeled after the Goldbergs’ but tailored to their interfaith marriage. It is but one exemplar of the many “homemade haggadahs” that have been created ever since it was discovered that you didn’t have to be a rabbi to cut and paste (first literally, later digitally) to arrive at a ceremony that felt theologically or politically relevant, and temporally realistic, given the length of your group’s attention span.

The Robertses began with “The New Haggadah” published by the Reconstructionist movement. Its first edition in 1941 got Mordecai Kaplan into trouble with his Jewish Theological Seminary colleagues, to whom he referred in his diary as “the great do-nothings who command positions of spiritual influence in Jewish life.” They assailed him for such sins ranging from his “unscientific” translation of karpas as “parsley” to the much more weighty offense of eliminating any reference in the text to the chosenness of the Jews. Responding liturgically to the many American Jews for whom the seder ritual had become “meaningless and uninspiring,” Kaplan intended to provide a haggadah that “could make of that service a living religious experience.” To their selections from Kaplan, the Robertses added prayers that he had omitted but to which their guests remained attached. They also added more narrative parts from Exodus and deleted anything that had a xenophobic ring to it (in the early 1990s, they made the requisite gender tweaks). The book they have published is a haggadah for interfaith families such as their own who have decided, as they did, to create a home in which the rituals of more than one religion are practiced.

Unlike the White House seder, which culminates, interestingly enough, with the traditional call of “Next year in Jerusalem,” the Robertses and their guests express their hope for “Next year in Bethesda,” and they do not mean the biblical healing pool in Jerusalem. Rather, the Robertses explain what they consider to be a truism: “For many American Jews, especially Jews in interfaith relationships, celebrating Passover in Israel is not a deeply held desire.” Wishing to hold more seders in Bethesda is the “more honest hope.” But there seems to be some confusion here. Whatever one’s politics, the haggadah’s aspiration to be in Jerusalem is not about booking tickets on El Al for a Passover at the King David Hotel nor even about settling in Israel. It’s about the “audacious hope” of a particular people, once saved, only to find itself in exile again and again. It’s about having the fortitude to overcome despair; it’s about homeland, nationhood. For some, it’s a heavenly Jerusalem that will descend to earth in messianic times; for others, it’s a dream of perfection towards which one can work. However it is understood, the idea of Jerusalem is a lot to give up in favor of, well, remaining where one is.

The Roberts seder is most hospitable to the Jew who likes the idea of a few traditional practices, but isn’t much interested in Jewish law or theology. If God is not absent from the Robertses’ haggadah text, it is because Cokie is a Christian who believes in a loving God who experiences Passover and Easter as completely compatible with one another. If in Jewish practice a blessing is said over bread, at the Roberts seder the matzah itself is blessed, made holy through the uttered name of God, as in communion. And Jesus is there too: He is beckoned at the singing of all verses of “We Shall Overcome,” originally a Christian spiritual before it became the anthem of the civil rights movement. One verse, which the Robertses include, begins, “We shall be like Him, we shall be like Him . . .” The source for it is, of course, John 3:2: “But we know that when Christ appears, we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is.”

I myself have witnessed the often intense and sometimes heartbreaking negotiations on the part of interfaith couples who seek to discern how and if sacred celebrations can be conjoined. Jewish culture layered with Easter Sunday works for the Robertses, but is not the right recipe for the many religiously educated, committed, Passover-experienced, and God-directed Jews who have no need to rely upon the non-Jews with whom they have linked lives to be what Mrs. Roberts’ husband jokingly calls “the better Jew.”

Serenely removed from such questions, back on the DC side of the Potomac, in the Library of Congress, sits the 15th-century haggadah known, on account of its nine-decade sojourn in our nation’s capital, as “the Washington Haggadah.” Harvard University Press has just issued a sumptuous facsimile edition, along with a translation of the Hebrew text and commentary by David Stern, a distinguished scholar of rabbinic texts at the University of Pennsylvania, and art historian Katrin Kogman-Appel, who teaches at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Serenely removed from such questions, back on the DC side of the Potomac, in the Library of Congress, sits the 15th-century haggadah known, on account of its nine-decade sojourn in our nation’s capital, as “the Washington Haggadah.” Harvard University Press has just issued a sumptuous facsimile edition, along with a translation of the Hebrew text and commentary by David Stern, a distinguished scholar of rabbinic texts at the University of Pennsylvania, and art historian Katrin Kogman-Appel, who teaches at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Stern frames his introduction as a biography of the haggadah. “The life of any haggadah,” he writes, “begins much earlier than the moment of its production.” It commences “with the formulation of its text, a process that took at least ten centuries; and that text itself derives from a ceremony, a ritual, that goes back to the earliest beginnings of the Israelite nation.” The roots of that ritual, the seder, have both pre-biblical and biblical origins and reflect a melding, over time, of practices marking the spring harvest of wheat and sacred national memories that would be “turned into watershed moments in the sacred history of Israel, the one commemorating the divine salvation of the first-born sons from death, the other the miraculous Exodus of the Israelites from Egyptian servitude.” But how did we get from the pilgrim’s family meal of matzah, bitter herbs, and lamb sacrificed at the Temple in Jerusalem to the symbolic “surrogate” meal and haggadah text that came in its stead when the Temple was destroyed? Although the Tosefta, Mishna, and Talmud give us glimpses of seder practices, we possess no written text older than the 9th or 10th century. The fragments we do have indicate that the earliest liturgy was not freestanding, but part of a prayer book. Stern apprises us of the different kinds of haggadah manuscripts that would emerge from the 13th century onward, when it became a book of its own, and takes us just to the cusp of the first printed haggadot.

The Washington Haggadah in particular “exemplifies the lives of Jewish books more generally.” Produced in Germany, it traveled to Italy, and then, before its arrival in America, “wandered across continents and through the lands of the Diaspora.” Its creator, scribe and illustrator Joel Feibush ben Simeon, was responsible for eighteen or so manuscripts that are still extant, half of which are haggadot. When the Jews were expelled from his native Cologne, he moved to Bonn, where he received his training. Exiled once again, he went to northern Italy. In this period, when he returned periodically to Germany, he created haggadot, siddurim, and machzorim. In Katrin Kogman-Appel’s assessment, Joel was a cultural agent, melding the “flatness and two-dimensionality of the spared-ground technique typical of German illustration” and the “Italian feeling for depth and detail . . .” The Washington Haggadah was not commissioned. Joel, confident in his artistic powers, knew a customer would come along, and left the end pages empty for personalization.

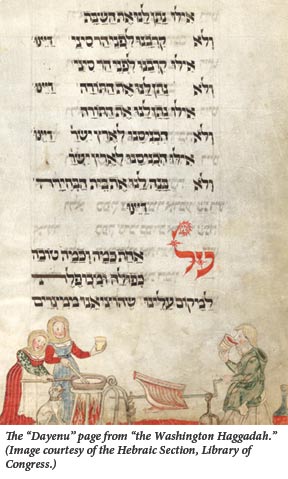

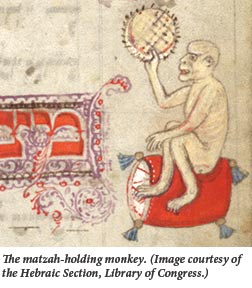

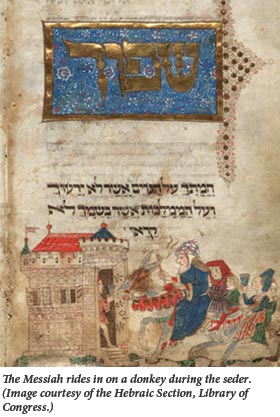

Joel is a very funny artist-imagine a 15th-century Roz Chast making haggadot. He loves visual puns, doodles with hide-and-seek gargoyles, and throws in a matzah-holding monkey (why? who knows?), all the while gently satirizing the denizens of his social world. My favorite three images are ones I see as a triptych on the battle of the sexes. The first is an image of a food preparation scene. On the right, there is a miserable fellow in a scruffy tunic turning the spit of a roasting rack of lamb. He is swilling a cup of wine, and there is an ample flask nearby for refills. On the left, there are two upstanding women (with their dog, why not?) stirring a pot of soup, one of whom offers a sobering cup to the man, as if to say in frustration, “Enough!”-it is, after all, on the “Dayenu” page—”Why must women do all the hard work?” The second image illustrates the passage on maror, the bitter herb, with a haggadah convention of textbook misogyny: An enormous husband attempts to stuff a bouquet of bitter herbs into his wife’s mouth, for she, as the joke goes, is his bitterness. His tiny wife holds her own, looking away and holding on to her double-edged sword for steadiness, even though that sword in Proverbs depicts the nasty sharpness that is woman. In the third image Joel whimsically resolves these images of marital strife with a goofy-happy, even eschatological ending: Giddyapping into a door of a medieval home comes a donkey, and on it the Messiah himself, and the whole happy and now harmonious family: dad, mom (this time, she’s the tippler), all the kids, and even granny (or a servant), hanging on to the tail for dear life.

Joel is a very funny artist-imagine a 15th-century Roz Chast making haggadot. He loves visual puns, doodles with hide-and-seek gargoyles, and throws in a matzah-holding monkey (why? who knows?), all the while gently satirizing the denizens of his social world. My favorite three images are ones I see as a triptych on the battle of the sexes. The first is an image of a food preparation scene. On the right, there is a miserable fellow in a scruffy tunic turning the spit of a roasting rack of lamb. He is swilling a cup of wine, and there is an ample flask nearby for refills. On the left, there are two upstanding women (with their dog, why not?) stirring a pot of soup, one of whom offers a sobering cup to the man, as if to say in frustration, “Enough!”-it is, after all, on the “Dayenu” page—”Why must women do all the hard work?” The second image illustrates the passage on maror, the bitter herb, with a haggadah convention of textbook misogyny: An enormous husband attempts to stuff a bouquet of bitter herbs into his wife’s mouth, for she, as the joke goes, is his bitterness. His tiny wife holds her own, looking away and holding on to her double-edged sword for steadiness, even though that sword in Proverbs depicts the nasty sharpness that is woman. In the third image Joel whimsically resolves these images of marital strife with a goofy-happy, even eschatological ending: Giddyapping into a door of a medieval home comes a donkey, and on it the Messiah himself, and the whole happy and now harmonious family: dad, mom (this time, she’s the tippler), all the kids, and even granny (or a servant), hanging on to the tail for dear life.

Stern traces the “afterlife” of this haggadah as well. I wish I could say it was as colorful a story as that of the Sarajevo Haggadah, which Geraldine Brooks fictionalized in The People of the Book a few years ago, but it’s not. Joel’s haggadah was purchased by a Jew in Germany and probably stayed there for quite a while, before moving to Italy. By the 19th century, it had come into the hands of a distinguished Provençali family in Mantua, who left wine drops and marginalia that suggest it was still being used at their family seders. In 1902, the haggadah was bought by Ephraim Deinard, the flamboyant book dealer, bibliographer, parodist, and polemicist (he despised both Hasidism and Reform Judaism and questioned the existence of Jesus).

Stern traces the “afterlife” of this haggadah as well. I wish I could say it was as colorful a story as that of the Sarajevo Haggadah, which Geraldine Brooks fictionalized in The People of the Book a few years ago, but it’s not. Joel’s haggadah was purchased by a Jew in Germany and probably stayed there for quite a while, before moving to Italy. By the 19th century, it had come into the hands of a distinguished Provençali family in Mantua, who left wine drops and marginalia that suggest it was still being used at their family seders. In 1902, the haggadah was bought by Ephraim Deinard, the flamboyant book dealer, bibliographer, parodist, and polemicist (he despised both Hasidism and Reform Judaism and questioned the existence of Jesus).

This brings us back to Washington. Deinard’s dream was to establish “a major Judaica collection in America’s national library,” the Library of Congress. The philanthropist Jacob H. Schiff financed the purchase of several batches of Deinard’s collection of almost 20,000 Hebrew manuscripts. Joel’s haggadah, called “Hebrew Manuscript #1,” arrived around 1916. Now enshrined as “a treasure,” it ceased its life as a functioning haggadah. However, a few years ago, Sharmila Sen, a Harvard University Press editor, was shown the Washington Haggadah while visiting the Library of Congress. Sen, a Bengali Hindi born in India who had never seen a haggadah or attended a seder, fell in love with the book:

At first with the material object itself-the parchment is exquisite, the illuminations so quirky and

charming, the calligraphy is beautiful. As the curator told me the story of the book, I wanted to bring

it back to the table . . . I found out that the last (and only) facsimile of this book was made almost 20

years ago and cost over $1000. I wanted this to be a book which would be . . . something real people

bring to the Passover table and not be afraid of a little wine spill or food stain . . .

That’s not likely to happen. The book Sen has produced is simply too gorgeous. The reproductions reflect the feel of parchment and the shine of the golden initial illuminations; the design by Annamarie McMahon is pristine, with the variations in color of the English type mirroring Joel’s varied palette, and even the binding, embossed in gold and copper hues, reflect Joel’s marginal decorative elements. Besides, after flipping back and forth between the facsimile pages and the English translation that follows it, struggling to keep the assembled guests on track, and longing for “Chad Gadya,” (a song not included until after Joel’s day), one might end up missing the Maxwell House. Where will we be seeing the The Washington Haggadah this Passover? Where else, but on our nation’s coffee table?

Suggested Reading

On the Importance of Booing Mayne Yiddishe Mame

How did Zionist elites create a new national identity for rank and file members whose ideals did not match their own?

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

A Maimonides in Monsey

Maimonides’s only son, Abraham, fought to protect his father’s rationalist legacy. Now a direct descendant has republished his works, and a new Maimonidean controversy is percolating in “yeshivish” circles.

Pancho Villa and the Star of David Men

When the Young Men's Christian Association began offering wholesome recreation to soldiers in 1916, Jewish leaders were as as worried about evangelism as they were about bars and bordellos.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In