Posthumous Prophecy

Though prolific as writers, readers, and hostages of history, modern Jews have rarely produced serious fiction based on the Jewish past. A famous but only partial exception to this is Milton Steinberg’s As a Driven Leaf. Steinberg’s novel tells the story of rabbinic Judaism’s classic heretic, the 2nd-century rabbi, Elisha ben Abuya, on whom the compilers of the Talmud famously bestowed the pungent epithet Acher, or “other.”

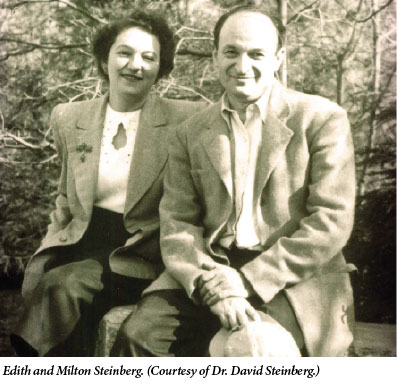

The 36-year-old rabbi of New York City’s Park Avenue Synagogue when the novel was brought out by Bobbs-Merrill in 1939, Steinberg was a trained philosopher who had been a favorite student of both Morris Raphael Cohen, at City College, and Mordecai Kaplan, at the Jewish Theological Seminary. He was known more widely as the author of 1934’s The Making of the Modern Jew, which concluded (lucidly, given the time) that history had left 20th-century Western Jews high and dry: their insular but sustaining past had been lost as a consequence of their having eaten from the fruit of the Enlightenment, while their way forward was blocked by Christian anti-Semitism. What Steinberg was not, however, was a storyteller, and the first submission of As a Driven Leaf was politely returned with the complaint that it was “almost entirely intellectual,” which was not a bad description of Steinberg himself, who then (with the help of his wife Edith, it’s said) reworked the novel into publishable shape.

The book received mixed reviews, and though it sold out its small first printing within two years, it made little money for the author. Stung, Steinberg told a friend he would never write fiction again, which turns out to have been almost true. After Bobbs-Merrill informed Steinberg it had no interest in a second edition, friends of the author urged the book on Behrman’s Jewish Book House, which then (as today, as Behrman House) specialized in textbooks for the Jewish day school trade. Behrman reissued the novel in 1948, and it has been in print ever since. Since 1980, it has sold more than 100,000 copies, according to the publisher. I tracked Driven Leaf on Amazon.com during February and March 2010 and found that it sold a little better than Marjorie Morningstar and lengths ahead of Exodus, Call it Sleep, Elie Weisel’s recent memoir, or any book by Martin Buber, Bernard Malamud, or Sholem Aleichem.

From a business perspective, therefore, it’s no surprise that Behrman House has spent the last decade or so trying to find a way to bring out a second Steinberg novel—an incomplete manuscript that the author was working on when he died of heart disease at the tragically young age of 46. This work-in-progress, called The Prophet’s Wife, was also an exercise in historical fiction, in this case an attempt at re-imagining the life of the biblical prophet Hosea.

Behrman began the project by trying to hire a brand name Jewish writer to complete the draft. According to former New York Times religion reporter Ari Goldman’s foreword to The Prophet’s Wife, Chaim Potok and Herman Wouk declined, while Goldman said yes and spent “many years . . . trying to craft a proper ending.” Ultimately, however, and for reasons neither Goldman nor the publisher’s chatty publicity kit make clear, Behrman House determined after all this to issue the novel in its original embryonic form, wrapped in warm apologias by Goldman, the novelist and essayist Norma Rosen, and Rabbi Harold Kushner of When Bad Things Happen to Good People fame.

The biblical book of Hosea is about fidelity: that of the people of Israel toward God, and that of Gomer, Hosea’s “wife of harlotry,” toward her husband. Neither marriage is working: Israel worships strange gods while Gomer strays. God ominously names her three children Jezreel, the site of a murderous royal usurpation; Lo-ruchamah, “no mercy”; and Lo-ammi, “not my people.” God’s promise, however, as voiced by Hosea, is that He will return love to a repentant people. Or as Steinberg sensitively put it in his Basic Judaism (1947), “Out of the capacity for forgiveness that he found in himself, [Hosea] leaped to the dazzling vision of a God inexhaustible in mercy.”

What Steinberg does with this biblical material is to mostly ignore it. The Prophet’s Wife, it turns out, is not about a prophet’s wife (or prophet), nor is it about Israel, idolatry, or God—who plays an abstraction of Himself in three brief and late cameos. Rather, it’s the story of a nebbish named Hosea who grows up on a rural estate in fruitful northern Israel along with his robust father, his robust older brothers, robust house servants—”ruddy” comes in for a lot of use—and lots of other robust and genial guys with appetites and habits that the priggish Hosea finds off-putting. This future prophet unwisely marries a little flirt named Gomer, who lives down the road apiece on a hardscrabble farm with her dissolute (but robust) uncle. One midnight, a year or so into the marriage, he returns early from a business trip and finds Gomer tangled in the “overripe redness” of one of those robust brothers. Hosea divorces Gomer (who turns to whoring) and becomes a scribe in the palace. One day, when rebels attack, Hosea sets down his quill, picks up a bow, and begins a long-range duel with an assailant who turns out to be—yes—the brother who cuckolded him. And there, with Hosea dodging his brother’s tossed spear, the book ends.

This tangle of clichés is made worse by the notable absence of cogent copyediting—a remarkable oversight given that the work was known to be a first draft, and the author known to have been composing it under great physical and mental stress, sometimes in an oxygen tent. Early on, for instance, we’re advised that except for children, “no one in . . . in all Jezreel laughed at Talmon,” the Shrek-like overseer of Hosea’s father’s estate. Two pages later, however, we read “whenever Talmon opened his mouth in song, all who heard him burst into laughter.” Then there are the temporary lapses into present tense that begin to occur near the 100-page mark, as though we’ve now got a clutch problem.

But as annoying as such bumps in the narrative road are, they are nothing as compared with the stylistic lurches the reader experiences when spoken conversation veers from the King Jamesian to something like True Confessions: “Seek not to brush me off so.” Then there is Hosea’s brother’s unintentionally hilarious response—this time a collision of King James and Vaudeville—when he’s caught in flagrante delicto: “Yet, it is not as bad as it appears.”

Nor did the editor care to do the late rabbi and us the favor of untangling a host of sentences like this one: “The world was multicolored, unhindered, where nothing came into being but found expression, an expression which never faltered and was ever true to the reality it bespoke.” Or (a personal favorite) “Her eyes burned black under eyebrows that glanced upward as though about to take flight.” And certainly something could have been done to solve the ambiguity of “As he had never desired anything in his lifetime, he wished to comfort her,” or the solid wrongness of “A rose may grow amidst briars, as the song says, but in my observation, only seldom.” (Actually, roses are briars, as the author of the Song of Songs is well aware.)

Of course, it’s hardly a crime to bring out an inept novel. And as copyright holders, Steinberg’s two sons—Jonathan, a distinguished historian at the University of Pennsylvania; and David, another historian and the longtime president of Long Island University—were certainly entitled to publish The Prophet’s Wife. My guess is that they did not view publication as a literary venture (Jonathan Steinberg once acutely characterized his father’s As a Driven Leaf as “half Danielle Steel and half Spinoza”), but as a matzevah, a permanent headstone for a famous father who died when they were still young. I saw some evidence of this at a book launch that took place in March in the sanctuary of the Park Avenue Synagogue. At the conclusion of the program, David Steinberg went to the bima and read the final paragraphs of The Prophet’s Wife, drifting into tears as he neared the end. “Those were the last words my father wrote,” he told us.

Berhman House, however, is not in the matzevah business. It’s a book publisher, and book publishers are not supposed to insult texts or the authors for whom they are responsible. The insult here is not merely editorial—again, an unfortunate commonplace—but an insult to probity and to Steinberg’s memory. It begins with a press release that describes the novel as a work “discovered [by Behrman House] deep within the archives of the American Jewish Historical Society.” In fact, not only has The Prophet’s Wife received consideration in every serious reflection on Steinberg since his death, but the American Jewish Historical Society archives are deep only as thoughts are deep and not as are the tombs of ancient Egypt. The Prophet’s Wife has been listed in a publicly available finding guide since 1981, and in an online catalog, for all the world to see, since 2003: “Creative Writing: Prophet’s Wife (manuscript) Box 10. ”

Having credited Behrman House with an archeological achievement, the press release goes on to ascribe a scholarly feat as well, in arranging for a “triumvirate of important contemporary writers” to enter into “an artistic and intellectual collaboration [with] Steinberg,” which in plain English means that the publisher, aware that it was releasing an unfinished book without artistic merit, had solicited essays from the likes of Goldman, Rosen, and Kushner so as to be able to present the project as scholarship, or even as a religious act. It’s no accident, certainly, that Rosen and Kushner’s afterwords are termed “commentaries” and are set within a “Reader’s Guide,” that includes “questions for discussion,” as though anticipating our need to gather as Jews around this text as we would around the Torah portion or a passage from the Prophets (the Book of Hosea, for instance): “What effect do . . . family dynamics have on Hosea’s outlook on God, community, and family?”

Let me take Harold Kushner’s essay first, because it is not only exemplary as a response to the book but also shows what might have been. Written with respect for the text and for the author in that it makes not a single extravagant claim for the novel, it honors Steinberg by offering a learned reading of the Book of Hosea, and of the intellectual and theological challenges that Steinberg faced in writing a novel about the prophet. Had the Steinberg family and Behrman House decided to publish the draft without fanfare, and prefaced it with Kushner’s article on the place of the prophets in rabbinic thought in the mid-20th-century, they would have had themselves a matzevah.

By contrast, Norma Rosen’s essay runs off the road with appreciations of Steinberg’s Gomer as a woman oppressed “by the iron hard social subjugation of her time” and of Milton Steinberg as a visionary proto-feminist who ventured where no rabbi of his time dared to go. It’s an absurd thesis, whether from a biblical or biographical perspective (though not quite as nonesensical as Rosen’s contention that the novel is elevated by “Vermeer-like detail”). Rosen then disappears completely into the ideological muck by referring to Steinberg’s “astonishing midrashic innovation” in making Gomer “a woman who is as independent minded as she is beautiful.” Let me be as clear as I can be: the Gomer invented for this book has no mind to speak of—only a feral cunning, some excellent dance moves, “curves of womanhood,” and an uninteresting but indiscriminate libido. She’s an ancient Israelite Jessica Simpson.

In his essay, Ari Goldman presents a brief hagiographic life of Steinberg, and generally extends the lifeless cheerleading he’d done for The Prophet’s Wife since pre-publication, as when he told a newspaper reporter that Steinberg makes the metaphor of God’s love for Israel “real and concrete and not just a metaphor.” But then he does something quite strange. Goldman lets us in on a conspiracy. He notes that the “official reason” The Prophet’s Wife wasn’t published immediately after Steinberg’s death was that it was “not something that could hold up as literary work.” But, he then whispers, “there was another reason.” And what was that reason? The book was “was too hot to handle,” Goldman writes. And why? Because Milton and Edith Steinberg had a “tempestuous marriage,” and “[t]he story of Hosea and Gomer cut too close to the bone.”

Certainly, those of us who have studied Steinberg know that his marriage to Edith Alpert was difficult. One wonders, however, what possible reason Goldman might have had to leeringly share this information except to gin up sales by allowing us to imagine that in The Prophet’s Wife we would not only be treated to a bit of novelistic midrash, but the marital truth about Milton and Edith. No one who reads Goldman’s introduction before reading the book will be able to encounter particular scenes and passages—Hosea’s disastrous wedding night, and his fevered thoughts about sexual pollution—without wondering things that don’t want wondering. Thus is the despoilment of the writer and man, Milton Steinberg—by publisher, editor, publicist, and attendants—completed.

Certainly, those of us who have studied Steinberg know that his marriage to Edith Alpert was difficult. One wonders, however, what possible reason Goldman might have had to leeringly share this information except to gin up sales by allowing us to imagine that in The Prophet’s Wife we would not only be treated to a bit of novelistic midrash, but the marital truth about Milton and Edith. No one who reads Goldman’s introduction before reading the book will be able to encounter particular scenes and passages—Hosea’s disastrous wedding night, and his fevered thoughts about sexual pollution—without wondering things that don’t want wondering. Thus is the despoilment of the writer and man, Milton Steinberg—by publisher, editor, publicist, and attendants—completed.

How will any of this affect Steinberg’s standing in 20th-century American Jewish history? Not a whit—and for three reasons. First, there’s his distinctive place in American rabbinic history. When the leaders of the Jewish Theological Seminary began to imagine a characteristically American synagogue rabbi who would be distinguished by his secular erudition as well as his Jewish learning and integrity, Steinberg came along to fit the bill. He was a poster rabbi not only for his elders but also for generations of rabbis (among them Harold Kushner) who followed him to the American pulpit.

Second, Steinberg’s status is also secured by the fact that he wrote wonderfully when he wasn’t writing fiction. His essays on Judaism are almost invariably smart, even wise, and occasionally lyrical. Basic Judaism remains in print because it is clearer, more learned, more generous, and lovelier to read than almost any of the popular accounts of Judaism that seem to tumble from the presses each season.

And finally there’s As a Driven Leaf, a novel that was probably just as awful in its first draft as The Prophet’s Wife remains, but was feverishly reworked by Steinberg, his wife, and anonymous editors at Bobbs-Merrill. They did not create a literary classic. In fact, most of the book’s characters are robed adjectives (loyal, clueless, wicked), and the one character who lives—Elisha—has an annoying habit of talking like a high school valedictorian practicing his very important speech in front of the mirror. But what they did make—what Steinberg himself made, ultimately—was a book that spoke to two great Jewish theological problems of both the 130s and the 1930s: a just God of Israel who does not intervene in the hideous maltreatment of his people; and the threat to those people posed by a secular civilization (Rome/America) that welcomes all comers. In the wake of the Shoah and then the virtual disappearance of consequential anti-Semitism in the United States, these issues became singularly important for American Jews, and so they remain, which is why As a Driven Leaf continues to sell, 71 years after its initial publication. The Prophet’s Wife will have no such luck.

Suggested Reading

Religion and Power

Rabbi Sacks, who is in the end an optimistic thinker, sees a process of internecine violence leading to religious moderation happening within Islam now.

Shaking Up Israel’s Kosher Certification System

On belly dancing, big government, and the issues of synagogue and state raised by recent attempts at kashrut reform in Israel.

Adventure Story

The story of Hebrew is a great story because there is nothing inevitable about it. Whether it was the period of the Bible or the Mishnah or Maimonides, there was always a danger, often the likelihood, that Hebrew would be lost in the break-up of great communities and subsequent migrations.

Notice Posted on the Door of the Kelm Talmud Torah Before the High Holidays

In the 1860s, Rabbi Simcha Zissel Ziv tried to found a new kind of yeshiva in which students would devote significant time to thinking about their moral lives.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In