Passport Sepharad

Last year, the legislatures of both Spain and Portugal passed laws encouraging Sephardi Jews to become citizens. To qualify they have to show that their ancestors were either among those expelled at the end of the 15th century or those who fled the Inquisition in the centuries after. Both countries are, of course, trying to make amends for old wrongs, and—this being politics—get multicultural credit and perhaps even some economic benefit for doing so. (The two countries are near bankruptcy.) Thousands of Sephardim in the United States, Turkey, Israel, and beyond have responded eagerly to the offers. Many, especially the Americans, have done so out of an abstract sense of historical justice or for the sheer novelty of having a second passport. Others, especially the Israeli and Turkish Jews, see Portuguese or Spanish citizenship as a shortcut to EU citizenship (which, indeed, it can be), a valuable commodity whether they intend to live on Iberian soil or not.

Although this story has received a fair amount of coverage, few have noted the way in which these new offers of citizenship tap into the long, rich, and complicated history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams that has been central to Sephardi life for centuries. One thinks, for instance, of André Aciman’s Uncle Vili in his brilliant memoir Out of Egypt. Uncle Vili became Italian “the way most Jews in Turkey did: by claiming ancestral ties to Leghorn, a port city near Pisa where escaped Jews from Spain had settled in the sixteenth century.” As Aciman memorably depicts him, Vili was a serial fabulist who served heroically in both the Prussian and Italian armies in World War I, worked as a spy for Great Britain in World War II, and, as a proud son of Alexandria, served as the auctioneer for deposed King Farouk’s property while living in a Georgian estate in Surrey under the name Dr. H.M. Spingarn, which was the name of an Englishman he had met as a child in Constantinople.

Vili’s story is fantastic. Still, it resonated with me as I conducted research in the archives of foreign ministries, consulates, private families, and Jewish philanthropies from Algiers to Vienna, Geneva to Tel Aviv, Lisbon to London, and Rio de Janeiro to Rome. Throughout the urban centers of the modern Mediterranean and Middle East, Jews have sought the legal papers, and protection, of foreign countries. In many cases, they never lived in the country whose papers they held, nor did they intend to. For instance, some self-proclaimed Bayonnese Jews were Sephardim whose families had lived in the Ottoman Empire for generations, even centuries, yet managed to come under the protection of the French Republic in the early 20th century based on a tenuous, unverifiable connection to the conversos who had settled in Bayonne after fleeing the Iberian Peninsula in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Thus, during World War I, the French foreign ministry suddenly found itself accountable for inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire, with which it was at war.

Some extraterritorial Jews were able to pass on their “foreign” status to children and grandchildren who themselves lived outside the Mediterranean region. Thus, one finds a Baghdad-born Jewish man in the 1920s who lived in Shanghai and held British papers inherited from a father who had received them a generation earlier in Calcutta and an Ottoman-born Jewish woman who lived all of her adult life in Brazil under the legal auspices of Portugal, a country on whose soil she had never stepped.

The pursuit of extraterritorial Sephardi subjects by the states of Europe, and Spain and Portugal in particular, is not new either. When the Ottoman Empire lost the port city of Salonica (now Thessaloniki), to Greece in the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), it still had the single largest Jewish mercantile population in southeastern Europe. Some 61,439 of the city’s 157,889 inhabitants were Jewish, most of them Ladino-speaking Sephardim whose ancestors had arrived in the Ottoman Empire in the century following the Spanish Expulsion. So many Sephardi exiles

settled in Salonica that it was one of the only European cities with a clear Jewish majority. In the course of the fighting, and in the face of anti-Jewish (and Muslim) violence, Jews were led to fear that Greek rule would be accompanied by a rise in anti-Semitism, and they began emigrating in rapidly increasing numbers. In the interim period between the Greek occupation of Ottoman Salonica in October of 1912 and the formal designation of the city as Greek, with the Treaty of Bucharest, in August of 1913, many Jews rushed to acquire the protection of European powers, in the hope that foreign papers would provide a measure of political security. Fortunately for them Spain, Portugal, and Austria-Hungary were eager to sign them up as protégés, or protected subjects.

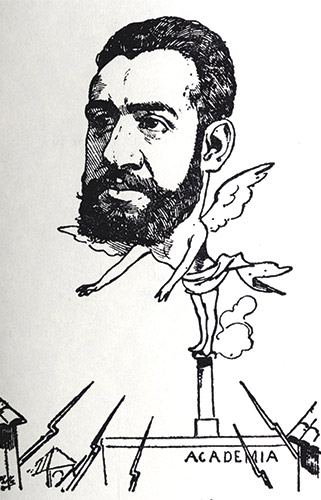

From the Spanish and Portuguese perspective, Sephardi Jewish protégés were a vehicle of colonial ambition. On the Spanish side, these ambitions had been voiced some years earlier by Ángel Pulido Fernández, a physician, anthropologist, and Spanish senator. Senator Pulido’s campaign centered upon the idea that Spain should reintegrate the Jews it had long ago “hemorrhaged” in order to help restore the commercial and cultural might it had lost more recently, when Spain relinquished the remains of its overseas empire in 1898, after the Spanish-American War. This claim informed not only Spain’s policies toward Ottoman- and Moroccan-born Jews, but toward those of other countries in years to come. In Salonica, Pulido’s dreams took tangible form. In November of 1912, in a letter to the president of the Paris-based international organization Alliance Israélite Universelle, the Spanish consul in Salonica extended protection to all Jews who “spoke Spanish and were of Spanish origin, whom modern Spain recognized as her sons.” By the end of 1913, the Spanish consul in Salonica had registered as Spanish subjects 175 Salonican Jewish men on behalf of their families, representing roughly 850 souls.

For reasons of its own, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy joined the action. In 1883, the Habsburg monarchy had secured the right to connect Vienna to Salonica by railroad, affording the empire a coveted outlet to the Aegean Sea and the promise of greater economic influence in the Balkans. Since these ambitions would be thwarted if Salonica fell into Greek or Bulgarian hands, Austro-Hungarian diplomats agitated for the transformation of Salonica into a free and neutral international city headed by a Jewish mayor. Simultaneously, the empire’s consular representatives encouraged Salonican Jews to apply to become Austro-Hungarian subjects. Beginning in the spring of 1913, the consulate registered approximately two-and-a-half times as many Sephardi men and their families as protected subjects as Spain had.

While all of this was happening in Salonica, the Portuguese parliament in Lisbon was debating an ambitious proposal to allow the massive settlement of Eastern European Jews in Angola. This plan, which was widely covered in the Ladino and French-language press of southeastern Europe, was inspired by the assumption that an influx of Eastern European Jewish immigrants would provide Portugal with a middle-class settler population to further its colonial ambitions. The proposal was ratified by a wide margin in June of 1913.

Portugal’s representatives in Istanbul and Salonica seized the opportunity. In Istanbul, Consul Mesquita began registering Ottoman-born Jewish subjects as Portuguese. At roughly the same time, Portugal’s honorary consul in Salonica, Jacques Missir, began registering select Salonican Jews as Portuguese subjects. The early months of 1913 found Consul Mesquita strenuously advocating the systematic addition of Salonican Jews to Portugal’s registration rolls—not simply as protégés, but as citizens. This tactic was in direct violation of the mandate of the Portuguese foreign minister, who had only granted his consuls in Istanbul and Salonica authority to approve “provisional registrations” for local Jews. Over the ensuing four months, the Portuguese consul in Salonica, Salomão Arditti (himself a Jew), registered 500 Jewish families as Portuguese subjects. So vigorous were Arditti’s efforts that he bought new printing presses just to produce passports. Portugal’s general director of administrative services described the machines as “magnificent in comparison with those of other consulates.” A typical passport embossed on Arditti’s press shows a young man nattily dressed, sporting a handlebar moustache, a polka dotted tie, and a carefully waved hairline, his expression cocky beyond what time or circumstance might dictate.

As it turned out, Arditti’s professionalism in producing passports provoked decades of confusion for paper holders and Portuguese state representatives alike. A handsome provisional passport, after all, could easily be mistaken for its permanent equivalent. Some Jewish families registered in 1913, unsure of the legal value of the papers they held—or, possibly, intent on maximizing their worth—found themselves commencing a decades-long bureaucratic dance with Portuguese officials. Thus, Mair de Botton (descendant of one of Salonica’s most distinguished rabbinic families) and at least 11 of his children registered in Salonica as Portuguese subjects. Over subsequent years and migrations, the family leveraged these registrations into other forms of official recognition. Mair de Botton’s children and at least four of their spouses were granted Portuguese passports from the consuls of Istanbul, Milan, Barcelona, and Rio de Janeiro; a brother obtained citizenship from the consul in Rome for his new wife, a French citizen who had become denaturalized upon her marriage to a foreign man. All told, the de Bottons appealed to no fewer than seven Portuguese consuls over a period of two decades.

The story of Salonica’s Jewish, Ottoman-born, foreign protégés did not end once the city became a part of the Greek state. In fact, it only became more complex with the passage of time and as the protégés themselves became more and more distant from the social context that rendered them “Austro-Hungarian,” “Portuguese,” or “Spanish.” Greece made every effort to impose Greek nationality on its so-called foreign citizens and to conscript their male youth in times of war. But individual women and men, and the Jewish community as a whole, proved immensely inventive in using the papers they had acquired or inherited. As late as the Second World War, possession of foreign papers could mean the difference between life and death, though they did not always help, since being an extraterritorial Jew could also render one extraordinarily vulnerable.

What became of the Salonican Jews who held foreign papers during World War II? When the Nazi occupation forces arrived in April 1941, about 50,000 Jews were still living in Salonica, virtually all of whom were deported to Auschwitz in 1943 and murdered there. When the deportations began, in early February of 1943, there were 860 Jews registered as foreign nationals still living in the city, including 511 Jews with Spanish papers, 281 with Italian citizenship, and six with Portuguese citizenship (most who had any sort of papers at all had already fled to France or Italy). Even as their genocidal plans were unfolding, German authorities were determined to avoid alienating neutral and allied nations, and therefore granted them the opportunity to “repatriate” foreign nationals from areas under German control. German and Spanish authorities began a back-and-forth over the future of the Spanish Jews in Nazi hands, which is agonizing to read even now. As Spain vacillated, Germany prepared to send Salonica’s Spanish Jews to Bergen-Belsen. At the last moment, Spain’s diplomat in Salonica, Sebastián de Romero Radigales, arranged for 150 Spanish nationals to flee Salonica for Athens (where they would later fall, again, under German rule). The remaining Spanish Jews of the city were forced onto trains. With this deportation, Salonica was rendered all but devoid of Jews. It would take six months for Spain to iron out an agreement accepting these 150 Jews as “repatriates,” after which they were “repatriated” with a degree of fanfare that arguably exceeded the circumstances.

Portugal was also slow and selective in opening its doors to its protégés from Salonica. While Prime Minister Salazar’s government granted entry to Jews from Hungary, the Netherlands, and Vichy France by labeling them “Portuguese,” it rejected the mandate set in 1912–1913 by the young Portuguese Republic, denying petitions from documented “Portuguese” Jews in Greece until nearly the end of the conflict.

Some perished in the Nazi death camps as a result of Salazar’s inflexibility, including the Benveniste family from Kavalla. In March of 1943, Saloman and Flora Benveniste, together with their son Moise and his wife Lucie, were taken from Kavalla to Bulgaria’s Gorna-Dzhumaya transit camp and from there (under the oversight of Bulgarian authority) by train to Lom, a port city on the Danube River. Even as this horrific journey was underway, a family member in Lisbon notified the Red Cross in Geneva of the Benvenistes’ plight. The Red Cross contacted Portuguese representatives in Switzerland, warning them (incorrectly, as it turns out) that the family was soon to be sent to Upper Silesia, that is Auschwitz. The Portuguese representatives inquired into the Benvenistes’ family history, but the information they gathered was not enough for Foreign Minister Eduardo Vieira Leitão. Unmoved by the fact that they were, in the words of the Portuguese mission in Switzerland, “Jews of Portuguese nationality” (“israelitas, de nacionalidade portuguêsa”) or by the fact that the administration had saved other Jews with more tenuous ties to Portugal, Leitão concluded that the Benvenistes’ claims to nationality were groundless. On March 18,1943, they were deported to Treblinka, where they perished.

Among the very first Jews killed on Italian soil in World War II were Jews from Salonica whose parents or grandparents had been Spanish or Portuguese protégés. Some of them had come to Italy before the war; others had fled there in the summer of 1943 with the help of an Italian official in Salonica named Lucillo Merci, who granted them papers to travel on. Five days after the armistice between the Allied forces and Italy in September of 1943, several of these families gathered in and around the town of Meina on Lake Maggiore, northwest of Milan. Alas, the region around the lake was occupied by the SS, which was on an aggressive hunt for Jews. Among those caught in their search were 20 individuals, including members of the prominent “Franko” families Fernandez Diaz, Mosseri, Torres, Nahum, Modiano, and Pompas, who had taken shelter in a hotel owned by Salonican Jewish Frankos named Alberto and Eugenia Behar. The SS confined the guests to the hotel, then, one by one, they were taken to the nearby lake, shot, and thrown into the water with stones tied around their necks.

Scholars of modern Jewish history have tended to view citizenship as a binary matter; something Jews either possessed or lacked. The story of Sephardi protégés and their descendants invites us to think of it, rather, as a spectrum. For the Mediterranean Jews who aspired to protégé status, as for the states that extended it, extraterritoriality was not simply a legal niche but a framework into which one could invest one’s fears, ambitions, and dreams. It was not a status that one received passively with birth, but it wasn’t one achieved by actual immigration either. It was an active legal, bureaucratic, and political achievement that required persistence, ingenuity, and luck.

Historically, as today, there were faultfinders. Jews and non-Jews criticized Sephardi extraterritoriality from a variety of perspectives—legal, xenophobic, communitarian, nationalist, Zionist, socialist, imperialist. Then, as now, the associated fees were described as overly steep, even vulgar. But despite obstacles and criticisms, over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Sephardi Jews continued to seek foreign protection. They were always in the minority, nonetheless, Sephardi Jews continued to remember and romanticize the protégé status long after the Ottoman Empire had been abolished. Indeed, the historical memory lingers among those who are tempted, for one reason or another, to claim citizenship from the countries that expelled their ancestors five centuries ago.

Suggested Reading

Athens or Sparta? A Rejoinder

Accused by Patrick Tyler of unfairness, Morris presses on.

When Canines Were in the Land

Did dogs save the Jewish State?

Problems with Authority

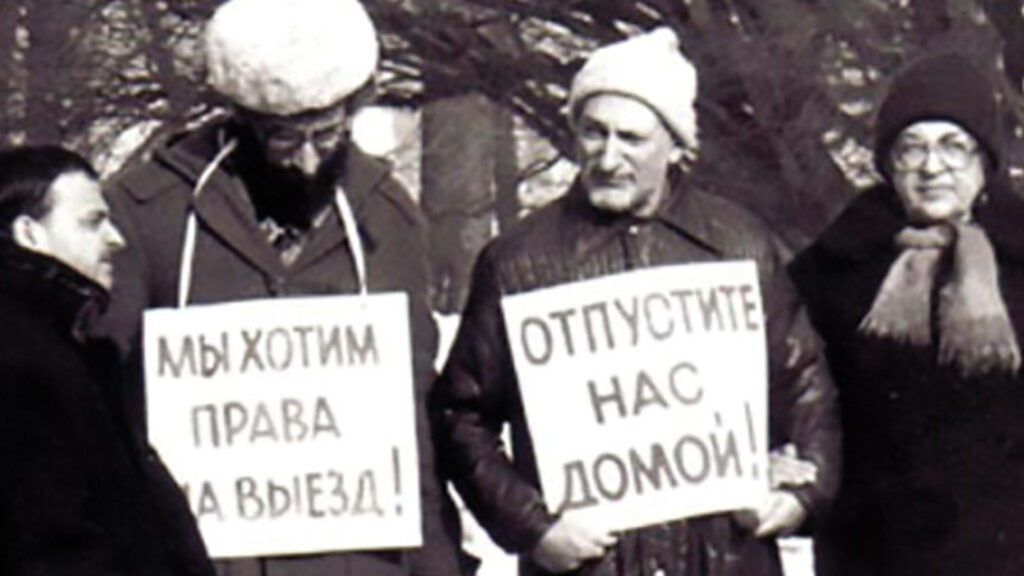

Paul Goldberg’s latest novel, The Dissident, is a narrative tour de force that plays far too fast and loose with the historical facts, leaving its readers deeply misled.

Mashed Potatoes and Meatloaf

From overly familiar ingredients, Joanna Hershon has concocted something that is both satisfying and unexpected.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In