Eight Poetic Fragments by Avraham ben Yizhak

Avraham ben Yizhak was the pen name of Abraham Sonne, who published only 12 poems in his lifetime. His silence was deeply charismatic, not least to the people who knew him. “Through Sonne I learned for the first time what a man’s integrity means,” wrote Elias Canetti, who befriended him in Vienna in the crackling years after the First World War, when Sonne lived in the eye of the modernist maelstrom and became acquainted with many of its luminaries. In his autobiography Canetti devoted many pages to the taciturn Jewish poet from the provinces, but the fullest and most affecting account of Sonne is Pegisha im Meshorer (Encounter with a Poet), the tender memoir of their friendship and their love that Lea Goldberg wrote shortly after he died. (“On my birthday, on May 29, Sonne died,” she noted in her diary. “Since then, really, nothing has any significance save for this fact.”)

With those 12 poems, Sonne transformed Hebrew verse. He introduced European modernism into it. “Avraham ben Yizhak was the first,” Bialik declared in 1927. And Goldberg: “He was the first Hebrew poet whose watchface showed not only the hour in Jewish time but also the hour in world literature.” There is a genuinely new music in these Hebrew poems, an unprecedented exquisiteness of diction and mood. Sonne was born in Przemyśl, in Galicia, in 1883 and died in Tel Aviv in 1950. He was a nationalist and an aesthete, a Zionist activist who preferred cafés to meetings and language to action. Not long before he died, he said of his work, “I always tried to capture a particular instant that contained the feeling of the things I had seen. I never spilled my soul.” His reader may be forgiven for finding feelings not only in the things but also in the poems. Sonne’s startling images leave a powerful emotional wake, the way classical Chinese poems do. Some of his lines are so gorgeous that one commits them to memory almost unthinkingly.

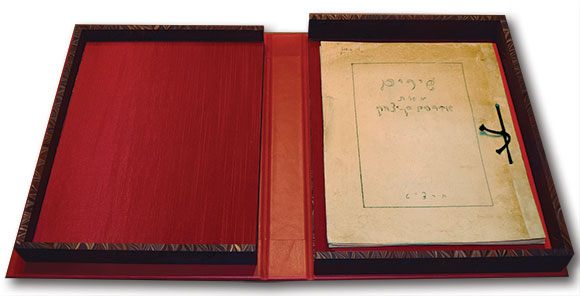

Sonne was averse to collecting his lyrics into a book; not even Bialik could persuade him to do so. In 1930, however, not long after Sonne’s immigration to the land of Israel, they were collected by Israel Zemorah into a booklet made of mimeographed paper, the sturdy consonants typed and the sprightly vowels added by hand in the old way, tied together with a thick black string. This humble edition was produced in 30 copies by the weekly Turim as a gift to its contributors. Some years ago I was lucky enough to acquire one of these treasures—the copy once owned by Reuven Barkat, who served as speaker of the Knesset in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Since the booklet was fragile, I took it to an extraordinary local bookbinder—a shrine to the art of the book not far from the White House—and asked that he design a protective case for it. When he presented me with his creation a few months later, I gasped. The lyrics of Avraham ben Yizhak were resting in a carefully constructed red envelope housed in a large clamshell box opulently manufactured of red calfskin with its corners hand-tooled in gold: the work of a master craftsman for the work of a master craftsman. I not only gasped, I also feared for my wallet. “Not to worry,” my friend assured me. “You said that this was an important document, and we had some materials left over from the box we built for the iPod that Obama presented to the Queen.” I laughed, I thanked him, I explained that for my people such things are indeed the crown jewels, and I carried Shirim me’et Avraham ben Yizhak out to Pennsylvania Avenue in perfectly condign splendor.

My translations of these fragments are based on Hannan Hever’s superb edition of the complete poems. He dates them to 1913, 1919, and 1924. I dedicate them to Harold Schimmel.

Do you know what I prayed for in these days

as I passed between the houses into which the

afternoon silence was gathered

the tough cypress standing tall before them

like a candle-soul reveling in its holiness?

I prayed that it would be given to me at the

fading of the day

to place my hand upon the bolt to your room

and find you draped in darkness

with just your head subsisting

in a golden sphere of restful light

and your fingers dispersed to the edges of the

piano

until the sounds rise and you are forgotten

and only your soul will make a stir

which will reach me.

rise

rise from the depths rise

from the dark places and the rubble rise

with your bleeding hands

and if your days were heavy there

and if the sun set in sunsets without end

rise.

Our first longings were like this:

like a blossoming branch facing the dawn

like flowers

like the disgrace of an arid land.

The lightning ate

my heart.

O lily of the valley whiteness of shame

I received a letter (from Sarah)

the stars reddened in their orbits, the heart

shed a tear. Like a bloom in a wasteland like

a bloom in a wasteland like a bloom in a

wasteland.

Let us raise the candles of the wind

in our darkness.

Lines all the way to the limits of joy

a face sweetened by pain

expiring in nets of gold, flowing

sapphires roaming above them

like a dream that stands still and will not pass

—Avraham ben Yizhak

Suggested Reading

Ireland and the Promised Land

Why isn’t Israel more like America, Jews from that country wonder. In his ambitious new book, Alexander Kaye instructively raises the question of why Israel isn’t even less like the United States.

Rethinking Jabotinsky: A Talk with Hillel Halkin

The Jewish Review of Books and Yale University Press hosted an evening for Hillel Halkin’s brilliant new biography of Vladimir Jabotinsky at YIVO.

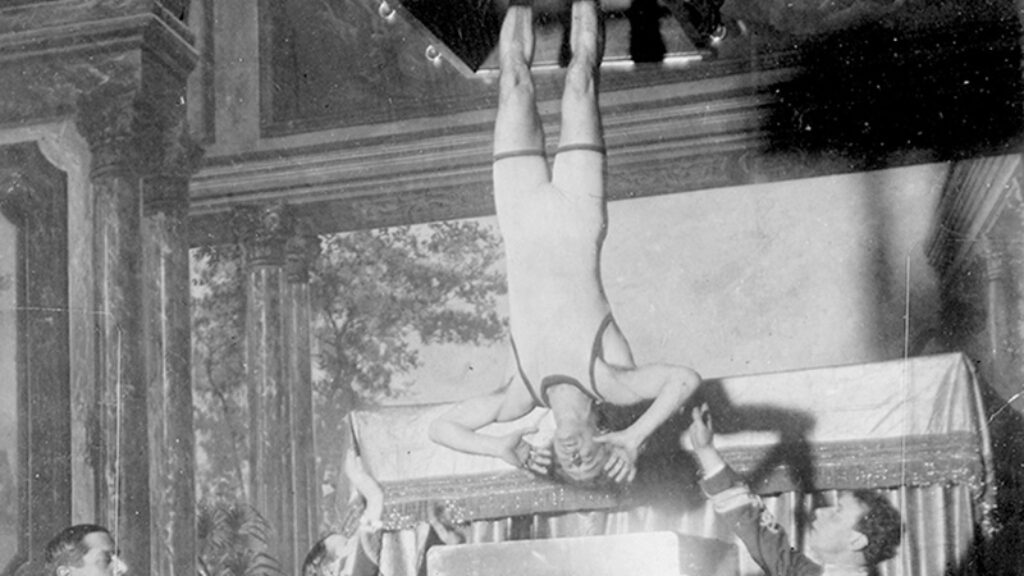

An Entrepreneurial American

“Houdini created his illusions and handed them down to his brother Hardeen, Hardeen sold them to the Amazing Dunninger, and Dunninger sold them to—my father,” writes Jerry Muller in his review of Adam Begley’s new biography of the great Jewish escape artist.

On the Separation of Yeshiva and State

What conservative activists call religious liberty is often a deliberate blurring of the separation of church and state. Orthodox Jews ought to worry more about this, even if it might mean some vouchers for day school.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In