The Audacity of Faith

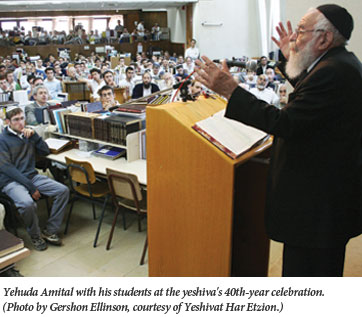

On May 27, 2005, some fifteen hundred of Rabbi Yehuda Amital’s disciples and admirers gathered in Israel’s International Convention Center to celebrate their teacher’s 80th birthday. Looking around at his former students, now leading rabbis, academics, activists, journalists, and soldiers, Amital, the rosh yeshiva (dean) of Yeshivat Har Etzion, was overcome by the thought of his passage from a Nazi labor camp to such a gathering, and spontaneously recited the she-hecheyanu blessing, praising God “who has granted us life and sustained us and permitted us to reach this time.” Later in the day, a short film was screened in which Mordechai Breuer, doyen of Orthodox Bible scholars, was interviewed about his friend of 60 years. “Such powerful faith and powerful intellect, I never understood how they didn’t clash, but with him, they didn’t. I don’t understand it even to this day.”

By Faith Alone: The Story of Rabbi Yehuda Amital, Elyashiv Reichner’s newly (and fluently) translated biography, is an attempt to understand an extraordinary man and his long, arduous path from a simple Jewish life in prewar Hungary to a unique and controversial place in Israeli religious and political life. It is essential reading not only for understanding Amital’s own story and the history of Religious Zionism but also for its portrait of a religious virtuoso who combined deep faithfulness with great daring.

Amital was born Yehuda Klein in 1924, in the Transylvanian city of Grosswardein (Oradea), home to Hasidim, acculturated and assimilated Jews, Jewish-Hungarian nationalists, and a large concentration of Hungary’s Religious Zionists. After rudimentary schooling, he spent his childhood and adolescence in yeshiva, under the tutelage of Rabbi Chaim Yehuda Levi, who had studied in the great study halls of Lithuania and brought their methods of conceptual analysis back to his native Hungary. At an early age, Amital discovered and was electrified by the writings of Abraham Isaac Kook, whose mix of passionate religious experience, Jewish nationalism, messianic fervor, and ethical universalism would set the terms for his later engagements.

His father was a tailor and he might well have become one too, had he not been forced to witness the murder of his culture. In May 1944, he was taken away to a brutal forced labor camp, but managed to sneak in an anthology of Kook’s writings with him. His family was sent to Auschwitz. Having twice sworn during his time in the camp that if he survived he would study Torah in Jerusalem, home to his grandparents and two uncles, he made his way there after his liberation. He threw himself into his studies at the Hebron Yeshiva in Jerusalem, acquiring a reputation for fervent, independent-minded spirituality, and for his mastery of halakhic literature. (Rumor had it that he had thousands of lengthy rabbinic rulings memorized.) Eventually he moved to Rehovot, and, though a penniless, orphaned survivor from an undistinguished family, married into one of the most prominent rabbinic families of the time, by dint of his learning and piety (and personality).

The day after David Ben-Gurion declared Israel’s independence, a Shabbat, Amital enlisted in the IDF. He fought in Latrun and in the Galilee in 1948, and founded a journal in which he published perhaps the first programmatic essay by anyone on being a Jewish soldier in a Jewish army. While savoring Jewish national self-defense in the wake of the Holocaust, he also projected Jewish law and values as a defense against the dehumanization and brutalization of wartime. In the Israeli assumption of Jewish responsibility for all of society, he saw the restoration of the primal force of biblical religion. His essay closed with Joshua’s call to the people, “make yourselves holy, for tomorrow God will work wonders with you” (Joshua 3:5). A short while later he Hebraized his name to Amital, based on Micah 5:6: “And the remnant of Jacob will be among many nations (amim) like dew (tal) from God, like droplets on the grass . . .”

Through the 1950s, Amital taught in his father-in-law’s yeshiva in Rehovot. In 1959, the two of them negotiated an arrangement (or hesder) whereby yeshiva students could alternate between military service and their studies. This arrangement blossomed into a widespread network of Religious Zionist educational institutions. In 1967, after the Six-Day War, Amital was asked to become the head of a new hesder yeshiva being established in the Judean hills near Bethlehem. The site of a number of (mostly religious) kibbutzim, Gush Etzion (the Etzion bloc) loomed large not only in biblical history but also in Israeli memory. After 1967, the children and survivors of the bitter fighting and massacres that occurred there in 1948 returned, and established Yeshivat Har Etzion in abandoned Jordanian army barracks.

Early on, Amital told the students that while Torah study was at the heart of their enterprise, the yeshiva would be a place where—in the words of a Hasidic tale he often quoted—the cacophony of the study hall, literal and figurative, would never be allowed to drown out the sound of children’s cries. “Every generation,” Amital said, “has its own cry, sometimes open, sometimes hidden, sometimes the baby himself doesn’t know that he’s crying.” He also made clear that he was there to challenge and to be challenged, that he expected his students to forge their own religious paths. He had no intention, he said, of creating “little Amitals.”

In assuming the deanship of Yeshivat Har Etzion, Amital joined the leadership ranks of Religious Zionism, one of whose other major leaders was Zvi Yehuda Kook, son of Amital’s spiritual hero Abraham Isaac Kook, and successor as head of his yeshiva. Both Kook and Amital saw God’s hand in history, specifically in the 1967 War and the liberation of Judea and Samaria. But while Zvi Yehuda Kook saw the Holocaust, too, as part of God’s plan, having forced Israel from exile and bringing about the creation of the Jewish state, Amital refused to see those horrors the same way.

The Holocaust certainly deepened Amital’s sense of awe at the times through which he was living—he often said, “My beard had not yet gone white, and I had seen in the course of my life, a world built, destroyed, and built.” The Holocaust did not shake his faith in God, but it placed an unanswerable question mark on any attempt to read His mind. “I have no doubt that God spoke during the Holocaust,” Amital said, “I simply have no idea what He was trying to say.”

In 1971, in a mix of humility and self-confidence practically unheard of in yeshiva circles, Amital invited Aharon Lichtenstein, an outstanding Talmudist at New York’s Yeshiva University, to head the yeshiva in his place, offering to serve beneath the newcomer as mashgiach ruchani, spiritual tutor. Lichtenstein, ten years Amital’s junior, accepted on the condition that Amital continue to serve alongside him as co-head of the yeshiva. Lichtenstein and Amital were an exquisite study in contrasts. The former had a PhD in English Literature from Harvard, and, as son-in-law of Joseph B. Soloveitchik, was heir to a distinctive Litvak neo-Kantianism. He was a tall, reserved, at times severe, intellectual, who projected a nearly Jesuitical asceticism. Amital, whose formal secular schooling had not extended beyond fourth grade, was compact and exuberant, spoke in Hasidic aphorisms, and unapologetically enjoyed fine whiskey and a good cigar. The harmonious and deeply respectful collaboration of such wildly different figures was perhaps the most powerful lesson their yeshiva has ever imparted. The two shared a rare conviction, that it was their job to teach yeshiva students not only Talmud but also to think for themselves.

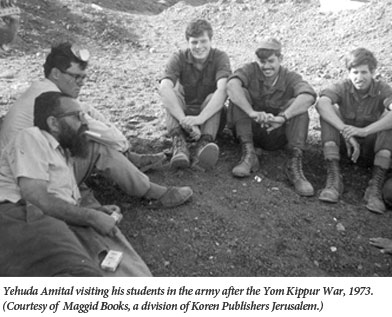

But the arrangement with the army inevitably brought war into the study hall. Eight students of the yeshiva, out of a total student body of some two hundred, were killed in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and many more were wounded. Overcome with grief, Amital handed the yeshiva over to Lichtenstein, and spent the war and months afterwards traversing the fronts, visiting field hospitals, bases, and outposts, to be with his students.

Amital’s theological response to the war appeared in a slim volume entitled Ha-ma’alot mi-Ma’amakim (The Ascents from the Depths). “It is clear that we are in the process of redemption through the path of suffering,” he wrote, adding “this obligates us in the mitzvah of crying out, of introspection, of contemplating our actions, so that we know that God awaits our repentance.” This soul-searching had to begin within the yeshivot themselves, especially with regard to ethics. One must ask, he wrote, “Not ‘who is a Jew?’ but ‘what is a Jew?’ . . . to ask questions bravely, with the bravery of the battlefield.”

The war quickened the messianic energies of the settler movement, which crystallized into the organization Gush Emunim (the Bloc of the Faithful), many of whose leaders and activists had been Amital’s early students at Har Etzion. His book, by framing the disastrous Yom Kippur War in eschatological terms, seemed to offer a way forward from the despair of the war, onto the hilltops of Judea and Samaria, and thus became a chief text for the settler movement. But Amital never entirely joined in, and his arguments with Zvi Yehuda Kook, Gush Emunim’s unchallenged leader, became even more significant. It was not only Kook’s understanding of the Holocaust as part of God’s redemptive plan that disturbed Amital, but also his assertion of spiritual and halakhic authority when it came to politics. Moreover, in prioritizing the Land of Israel above almost every other religious value, Amital argued, Zvi Yehuda Kook had drained his father’s teachings of their universalistic elements. Amital’s Zionism was “redemptive,” but it was not “messianic,” and it placed the Jewish people and Torah before the land.

Through the 1970s, Amital continued to move further away from the settler vanguard. Reichner notes that in the wake of Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem in 1977, and the Knesset’s approval of the Camp David peace plan, Amital and Lichtenstein were the only hesder leaders who entertained the possibility of what would later be called “land for peace.” For Amital, the possibility of peace (or even the mere postponement of war), confirmed his sacred reading of Jewish statehood, since “the inner meaning of the recognition of the State of Israel by some Arab nations is the recognition of God’s Kingship.”

In 1982, Amital’s anguish over seeing students go to war once again flared into outrage with his discovery of Ariel Sharon’s lying to the government about the aims and prosecution of the incursion into Lebanon. He publicly opposed the IDF’s assault on Beirut, and in response to the Sabra and Shatila massacres issued a public statement: “We now stand four days before Yom Kippur. My entire being quakes and trembles out of fear for the Day of Judgment, for as is known, Yom Kippur does not atone for the sin of chillul Hashem (desecrating God’s name).” He and Lichtenstein were practically the only rabbis to call for the inquiry into the massacres that resulted in the Kahan Commission. Many Religious Zionists increasingly saw Amital as a renegade.

Even on the Left, he was as unconventional, unpredictable, and free of clichés as he had been on the Right. In December 1982, he addressed the founding meeting of Netivot Shalom, a religious peace movement (fledgling, then and now) and inveighed against what he said were the three false messianisms stalking the land: Gush Emunim, Peace Now, and that of Ariel Sharon. Each, he said, presumed to solve complex questions with a single simple answer, respectively: faith, good intentions, and force. But, he said, we need all three, and the wisdom of balance.

In 1985, at a conference marking the elder Kook’s 50th yahrzeit, he laid out the theological foundations of his position. Like Kook’s, Amital’s Zionism was not a response to anti-Semitism:

The yearning for redemption is rooted not in the [Jewish] people’s terrible suffering, rather the desire to do good for humanity is the essence of its soul.

This, from a Holocaust survivor, was astounding. Promoting a universal ethical vision, he said, must be of the essence of Zionism, not only to save it from the moral hazards of violent chauvinism, but precisely because the ethical message is itself the divine word that Israel is charged with spreading. As he later explained to an interviewer, the difference between his vision of Israel as “a light unto the nations” and Ben-Gurion’s, was rooted in the fact that without a divine foundation, ethical universalism would not survive.

In 1988, at the urging of supporters, Amital founded a political party, Meimad, offering a centrist religious voice on both political-diplomatic issues and relations between religious and secular Israelis. Everything that made the party appealing to well-wishers and observers—its non-dogmatic stance, the manifest absence of political ambitions on the part of its leaders, its mix of religious conviction with political liberalism—made it an electoral disaster in the rough-and-tumble world of Israeli politics. It failed to receive even one seat, though the party itself survived in truncated form, eventually resurfacing in the late 1990s as a one-man faction in the Labor party; today it no longer exists, and the moderation it represented is still a minority position at best within the world of Religious Zionism.

After the elections, Amital returned to his yeshiva and abandoned political life, until late 1995, when, in the wake of the Rabin assassination, he was asked to serve as a Minister without Portfolio in Shimon Peres’ short-lived government. This he did, hoping that his presence would ease, even a little, the terrible fissures then rocking Israeli society, and counteract the desecration of God’s name wrought by the yarmulke-wearing assassin. He pursued various initiatives in public health, education, Israel-Diaspora relations, and the ever-elusive goal of fostering dialogue within Israeli society. When the Peres administration was done, he returned to Har Etzion. His leftward moves cost him many supporters, and his natural role as the premier leader of Religious Zionism. But he was at peace with the course he had taken.

Amital concentrated his remaining energies on his yeshiva, only occasionally returning to public debate. In earlier decades, he had introduced elements of Hasidism and existentialism into Religious Zionist education. Now, he thought the pendulum had swung perilously close to self-absorption, and he became a critic of what he saw as a fetish of personal authenticity. He still believed that one must bring one’s own unique and individual personality to the religious life, but maintained that that very personal search must be anchored in social and political responsibility and a basic commitment to the tradition, even at its most prosaic.

In his late 70s, he proved his unconventionality once again by announcing that he would step aside, and let a search committee appoint his successor. In a yeshiva world regularly wracked by bitter succession struggles, often waged among sons and sons-in-law, this was, Reichner correctly says, a final instance of “his sober and realistic vision.”

Amital published little, but his later years saw the appearance of several volumes by and about him: A World Built, Destroyed and Rebuilt, a study of his thinking on the Holocaust by Mosheh Mayah; Resisei Tal (Droplets of Dew), a sampling of Amital’s technical talmudic and halakhic writings; Jewish Values in a Changing World (the Hebrew title was the Psalmist’s “And the earth He has given to humanity”) in which he lays out his religious and educational credo; Commitment and Complexity, a collection of brief, topically arranged aphorisms, quotations, and excerpts on a wide range of issues; and a Hebrew booklet, Between Religious Experience and Religious Commitment, critiquing the neo-Hasidic and existentialist currents in the Religious Zionist world that he himself had set in motion decades earlier.

Further posthumous books are reportedly in the works, and a memorial volume of reminiscences and studies of him has just been published. The title of that collection, Le-Ovdekhah be-Emet (To Serve You in Truth), is that of Amital’s favorite niggun, or tune, which he fervently taught generations of students. The words capture the rootedness of his bracing commitment to authenticity and questioning in a simple, pure faith. It is hard to imagine another figure on the Israeli scene who could bring Shimon Peres, the proponent of Oslo, and Shlomo Aviner, the Religious Zionist hardliner, within the covers of one memorial volume.

The faith and piety of Amital’s Hungarian childhood never left him. Many of the questions at the center of modern Jewish thought simply didn’t bother him. God’s existence and providence, the divine origin of the Written and Oral Torah, the binding power of rabbinic tradition and law, and the Jews’ unique role and destiny were all for him simply axiomatic. It was perhaps this unaffected, almost guileless faith and deep identification with “simple Jews” that freed him to embrace complexity, even as he expressed his ideas with powerful conviction.

Amital did not leave behind him a system or set of doctrines, but a cluster of powerful, provocative ideas, and an example from which we can learn as we each go about building our moral and spiritual lives. He wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

Suggested Reading

Our Man in Beirut

The Arab Section, suggests Matti Friedman, in one of his latest book's nicer lines, “needed men idealistic enough to risk their lives for free, but deceitful enough to make good spies.”

Jacob Glatstein’s Prophecy

Literary masterpieces that double as works of prophecy have been rare since the death of Isaiah. But the Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein wrote two novellas that foreshadowed the future of Jewish Europe.

Our Challah Moment

America is having a challah moment that coincides with two food movements in popular culture.

The Argumentative Jew

The most common understanding of disagreement, in the private sphere and the public one, is that it represents a failure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In