The Hasidim: An Underground History

Postwar American Jews learned of Hasidism largely through the romantic renderings of Martin Buber and Abraham Joshua Heschel, the photographs of Roman Vishniac, and—after the 1960s—through the popular evangelism of Chabad or the liberal appropriations of the Havurah and Jewish Renewal movements. Of course, some encountered Hasidim in the streets of New York or Miami, but for most of us, Hasidism was what our treasured authors wanted us to believe it was: a movement in love with God, the world, and fellow Jews. Many of us read the books of Buber & Co. because they seemed to reflect our values, our non-conformity, our spiritual restlessness. As the historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi wrote in 1982, “The extraordinary current interest in Hasidism totally ignores its theoretical bases and the often sordid history of the movement.”

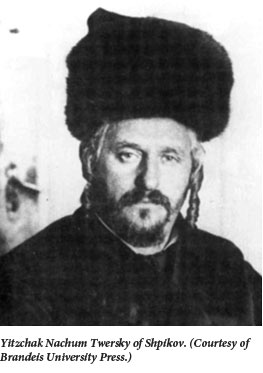

In Untold Tales of the Hasidim: Crisis and Discontent in the History of Hasidism, Israeli historian David Assaf uncovers some of that sordid history, but he isn’t much interested in its theoretical bases. Assaf’s book isn’t about Hasidic texts or ideas, nor is it about Hasidism; it’s about Hasidim. Assaf recounts a series of lurid and pathetic tales from what one might call the “clandestine history” of the 19th-century Hasidic movement: the rebbe’s son who converted to Christianity, sainted Hasidic leaders who went insane or found themselves in embarrassing circumstances, and still others whose piety primarily consisted of beating up opposing sects and using their rivals’ sacred texts as toilet paper. Assaf introduces the reader to Hasidic rebbes who ride into small towns like aspiring cattle barons, terrorize the inhabitants, and take over the place. (If cowboys were Hasidim, this would be Deadwood.) However, in the last chapters of the book, Assaf also introduces us to three enlightened Hasidic teachers who have been largely erased from Hasidic memory. The book ends with a reproduction and translation of a long, tragic letter by one of these figures, Yitzchak Nachum Twersky of Shpikov, lamenting his life in this “tiny, ugly world.”

Assaf does not narrate the history of 19th-century Hasidism directly. Rather, he proceeds by examining the self-representations and polemics, the histories and counter-histories of Hasidim and their opponents, who included both the modernizing proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment (maskilim), and of the anti-Hasidic mitnagedim of the rabbinic establishment. Untold Tales shows us the mudslinging, biting, and nail-scratching way Hasidic history was first made, unmade, remade, distorted, concealed, and contrived. It also suggests that the polemics against Hasidim by the maskilim and mitnagedim were no better, and often worse, than the one-sided, paranoiac Hasidic self-fashioning. Like the writings of the neo-Hasidic romantics, those of the Hasidim, maskilim, and mitnagedim reveal at least as much about their authors as they do about the Hasidim they depict. Nonetheless, out of these juxtapositions, the elements of a raw, unsettling clandestine history do emerge.

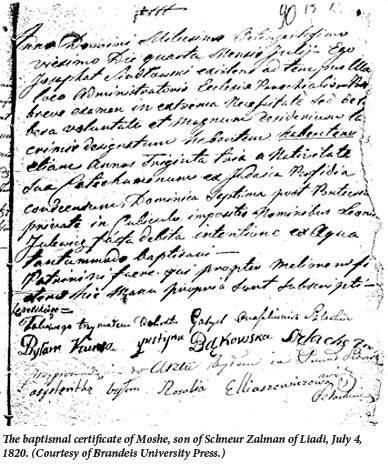

Perhaps the most resonant chapter of this book is a detailed account of the sad story of Moshe, the youngest son of Schneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of Lubavitch (also known as Chabad) Hasidism, who converted to Christianity. The story is well-known. Indeed, by the 20th century most internal Hasidic sources acknowledged Moshe’s conversion while focusing on his apparent mental illness and subsequent lifelong quest to repent for his action. However, in the 1920s, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, boldly rewrote the episode, denying Moshe’s conversion and, consequently, his need for repentance. This, in turn, generated a whole new apologetic literature. Assaf shows how, in this case, the power of the rebbe derives as much from his ability to rewrite the past as from his ability to predict the future.

The second tale Assaf examines is that of the mysterious and infamous death of Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz, better known as “the Seer of Lublin.” The Seer was perhaps the most renowned Hasidic rebbe of his generation and was the founder of Polish Hasidism in the 19th century. He was a rebbe’s rebbe, the teacher of some of the central Hasidic figures in subsequent generations, including Elimelekh of Lizhensk and Simcha Bunim of Przysucha. As a result of his popularity, the Seer was the target of vehement attacks. (An early anti-Hasidic pamphlet referred to him as both Nimrod and Balaam, two of the more villainous figures in the Jewish imagination.)

On the eve of Simchat Torah in 1814, the Seer fell out of a window into an alleyway, where he was found gravely injured, lying face down in urine and feces. Some of the local mitnagedim celebrated the news, perhaps viewing this as the downfall of Hasidism itself. When, nine months later, on Tisha b’Av, he died from his injuries, Hasidim and their opponents wrote very different obituaries. Assaf quotes Yitzchak Gruenbaum, a leading Polish Zionist born more than 60 years after the Seer’s death, whose father and mother passed on two of the leading theories of the Seer’s fall:

According to my mother’s tale, the Seer foresaw that the Messiah was to descend from heaven on Simchat Torah and that he must go forth to greet him. The rabbi decided to . . . ascend at what he calculated was the moment that the Messiah was beginning his descent to earth. He opened the window, stood on its sill, and went. He failed to rise, broke his neck, and died.

In my father’s version this was a simple matter, the Rebbe, who drank copiously in honor of Simchat Torah, fell from the window and was killed.

Still others depicted the fall as a suicide, perhaps out of despair that Napoleon’s Russian campaign didn’t usher in the Messiah, or perhaps out of simple insanity. Assaf writes:

It is highly unlikely that the actual circumstances of the Seer’s fall will ever come to light, nor is it important that they do so. Yet close examination of the different versions of the fall highlights the satirical-polemical stamp in each and reveals the convoluted paths of memory building, which are not always guided by the truth as it was.

Today, visiting the grave of the “holy Seer” of Lublin is a regular part of the itinerary of many Orthodox trips to Eastern Europe. These trips are populated by descendants of Hasidim, maskilim, and mitnagedim, most of whom are unaware that some of the venerated rabbis of the past, as well as some of their own ancestors, celebrated the Seer’s demise.

Assaf also recounts the very ugly history of what can only be called “Bratslav-bashing” on the part of various Hasidic groups, mostly during the 1860s. Again, this story is well-known but Assaf brings it to light in gory detail. Here we are introduced to Hasidic imperialism and “wilding” at its worst. The guiltiest parties were the Talner and Savraner Hasidim who acted more like marauders and thugs than pious disciples of the Baal Shem Tov. But here again, history is a trickster. The Talner and Savraner Hasidic sects have all but disappeared, while Bratslav is one of the most powerful Hasidic groups in Israel and has a worldwide following.

It is worth noting that neo-Hasidic romantics, from Martin Buber to Shlomo Carlebach, have given us portraits of Nachman of Bratslav and his disciples as proto-existentialists, the Lubavitch dynasty as a paradigm of holiness and purity, and the Seer of Lublin as the magisterial figure of early Hasidism. Assaf’s history doesn’t entirely belie or negate such characterizations, but it certainly complicates them. In these chapters, Assaf shows us how Hasidic historiography began as a bloody three-way battle between Hasidic apologists, mitnagedic vultures, and maskilic parodists. Contemporary historians are caught in this thicket (to invoke the original Hebrew title of Assaf’s book, which alludes to the entangled ram at the binding of Isaac).

Somewhat surprisingly, Assaf does not leave us in the thicket. In the second part of the book, he abruptly turns to three tragic Hasidic figures who were written out of Hasidic historiography because of their positive appraisal of elements of modernity. Such teachers would very likely be venerated by romantic ba‘alei teshuva and academicians alike, if only they knew of them, but in the era before Hasidic romanticism merged with countercultural spirituality, such religious figures had no audience. And so Rabbis Akiva Shalom Chajes of Tulchin, Menachem Nachum Friedman of Itscan, and Yitzchak Nachum Twersky of Shpikov had virtually no influence on their successors and remain unknown.

These chapters also differ from the previous ones in being active historical retrievals of forgotten figures rather than second-order, comparative readings of earlier historical discussions. My guess is that Assaf thinks that Hasidism held, perhaps even still holds, the potential to offer the contemporary Jewish world a template for religious, spiritual, and cultural meaning. Yet it often undermines that potential by getting mired in pettiness, bigotry, and hatred. In Assaf’s view, the tragedy of these figures is not the same as that of the poor Bratslav Hasidim who were beaten to a pulp by the Talner and Savraner Hasidim when they traveled to their rebbe’s grave in Uman. The tragedy is that they might have saved Hasidism from itself.

For Assaf (and here I am taking some critical license), Hasidic historians helped destroy their own movement. In their attempt to protect Hasidic society from mitnagedic and maskilic attack, they undermined the potential for Hasidic creativity by writing some of their most interesting figures out of the movement. Neo-Hasidic romantics, on the other hand, chose to ignore rather than confront the debauchery of Hasidic life, and in doing so, offered unrealistic and indefensible portraits of these masters that will not bear the weight of historical analysis. The Hasidic, and later Haredi (often called “ultra-Orthodox”), mainstream did not take seriously enough the necessity of adapting to new social and intellectual circumstances. Of the thoughtful and courageous Menachem Nachum Friedman of Itscan, who tried to integrate elements of modernity into his Hasidic world, Assaf asks how the surrounding Hasidic society reacted to “such a complex, unusual phenomenon as Friedman.” The answer? Not too well; it rejected him and his innovativeness.

Assaf portrays Twersky, Chajes, and Friedman as men who understood the deeper challenges of modernity and attempted to initiate an internal critique of their society. They each failed. It was not only that they were rejected in their time but—just as importantly—that they were erased from historical memory. What has survived in Israeli Haredi society might be described as the continuation of the lamentable insularity that Assaf chronicles in the first part of the book. In contemporary Israel, where Assaf lives and works, this Haredism has both won and lost. The Haredim have become a tremendous political force and a moribund spiritual resource. The story, however, is far from over. Today there are spiritual descendants of Twersky, Chajes, and Friedman (many of whom likely never heard of them) constituting a kind of neo-Haredism that is less tied to the dynastic structure, more synthetic in their work, and more open to non-Haredi worldviews. In this sense, Assaf’s book is a much needed addition to work being done by Jonathan Garb, Boaz Huss, Jonathan Meir, Aubrey Glazer, and others in Israel and the diaspora who study neo-Haredi sub-cultures.

As a post-ideological historiographer of Hasidism, Assaf teaches its devotees a lesson: Many of the figures whom you romanticize acted in ways that were grotesque. Such criticism is not meant to subvert or destroy Hasidism as mitnagedic polemics and maskilic parodies intended. The mitnagedim and maskilim hated Hasidism. Assaf does not, at least as I read him. Rather, he is trying to salvage Hasidism from the mitnagedic and maskilic slaughter-knives as much as from the neo-Hasidic lava lamp. To understand the phenomenon called “Hasidism” one must also understand Hasidim. And to understand the latter one must look behind the holy books and into the dark corners of their sometimes unholy lives.

Suggested Reading

Irving Kristol, Edmund Burke, and the Rabbis

Irving Kristol started off as a neo-Trotskyite and famously became the “godfather of neoconservatism.” But his idiosyncratic “neo-Orthodoxy” lasted a lifetime.

The Home Front

Eating very long breakfasts, lunches, and dinners with dozens of aging members of the Greatest Generation was the best part of Arkush's teaching experience.

Shifting Sands

Shlomo Sand believes that nations are, in the nature of the case, modern inventions, and that Israel is a particularly bad one.

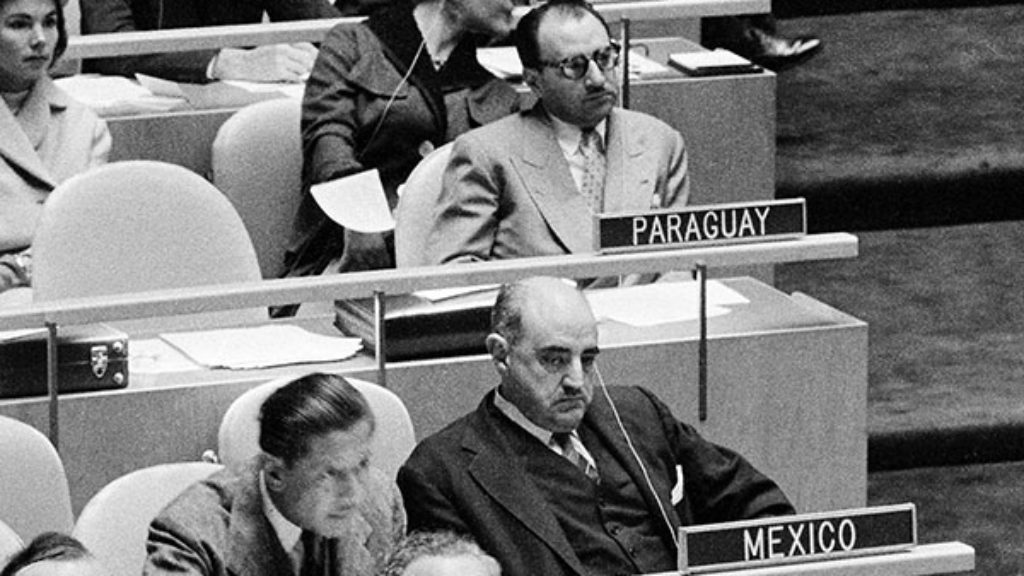

Universal Rights and the Particular Jew

Jews, like so many other minorities, whether they had states or not, deserve recognition and protection as nations. But these universal rights have eluded Jews, even as they worked to ensure them for others.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In