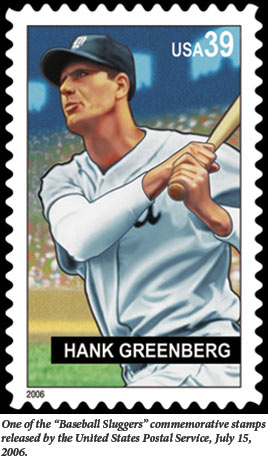

The Rise of Hank Greenberg

In his short story “Perfection,” Mark Helprin re-imagined Bernard Malamud’s “Natural” as an adolescent Holocaust survivor whose otherworldly ability to hit home runs every at-bat comes from understanding the spiritual balance of God’s creation. He temporarily redeems the ‘56 Yankees before exchanging athletic perfection for the simple life of a Hasidic child. Helprin’s story is the most “Jewish” of all baseball stories, seamlessly blending theology with the myths of the game. Part of what makes baseball unique is the way fact and fiction combine in the minds of its fans. If we can’t quite imagine a prodigy ba’al shem perfecting the sport, we can imagine a mighty Jewish slugger so devout that he refuses to play on holidays, even if it’s not quite true. The closest a Jewish hitter has ever been to perfection came in 1938, when Hank Greenberg hit 58 home runs for the Detroit Tigers, only two shy of Babe Ruth’s record. Four years earlier, Greenberg had refused to play on Yom Kippur, but, as Mark Kurlansky tells us in the prologue to his new biography Hank Greenberg: The Hero Who Didn’t Want to Be One, his decision wasn’t really a religious one. The Tigers were in a tight pennant race with games scheduled for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Greenberg, having his first great season, had not stated his plans, leading to intense speculation by the press and Jewish community as to whether he would play. A local Reform rabbi noted that the Talmud mentions children playing in the streets of Jerusalem on holidays, though he neglected to mention that these were Roman children. An Orthodox rabbi ruled that Greenberg could play on Rosh Hashanah under three (impossible) conditions: Orthodox Jews could not buy tickets for the game; no smoking could be allowed in the stadium; and all the food served in the ballpark had to be kosher. On Rosh Hashanah, Greenberg went to shul, then the ballpark and hit two home runs. (“Hank’s Homers are Strictly Kosher,” said the Detroit Free Press.) When it came to Yom Kippur, his Romanian-born father was quoted in the New York Evening Post assuring readers that his son would not play on Judaism’s holiest day. As in The Jazz Singer, which had been a hit only seven years earlier, the Americanized son fulfilled his religious and filial duty—though by that time the Tigers already had a lock on the pennant. Kurlansky’s prologue is the high-point of a disappointing book, the one moment when he actually re-frames one of the famous events of Greenberg’s career. While Hank Greenberg no longer has the same resonance with American Jews as Sandy Koufax, he has been the subject of several books and a well-regarded documentary. For most of the book, Kurlansky reproduces the familiar Greenberg narrative: where he played, what he hit, the anti-Semitism he faced, and what he meant to Jews during his life and times. Kurlansky occasionally suggests other, more interesting, ways of telling Greenberg’s story, but he resists pursuing them, effectively forgoing the opportunity to add to our understanding of Greenberg’s life. Hank Greenberg was one of the best offensive first basemen in baseball history, and he approached the game in a unique, even beautiful way. In his elegant little book on the aesthetics of sports, In Praise of Athletic Beauty, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht criticized sports books for focusing on biographical details instead of providing “materials or even suggestions for our visual imagination.” Kurlansky reproduces traditional statistics for individual seasons but provides very little description of how Greenberg played the game. Ironically, there is a chapter called “A Beautiful Swing,” but it contains only one paragraph that actually praises Greenberg’s style: “the bat sliced through the air, propeller-like, with such clean speed and power that it was hard to believe it was a man-made motion.” Whether or not one finds the description helpful, it is at least an honest attempt to describe how Greenberg hit, and what it might have felt like to watch him do so. By contrast, Kurlansky hardly attempts to describe Greenberg’s fielding. He reproduces the old judgment, without checking if it is historically true, that Greenberg was “a mediocre defensive first baseman” who was “not particularly graceful,” and had to practice diligently just to make routine plays. While defensive baseball statistics are notoriously less developed than those for hitting and pitching, the numbers we have (a career .991 fielding percentage at first base) suggest otherwise. The last thirty-years have seen the development of new and more fine-grained statistics that have changed our understanding of baseball, and Greenberg succeeds by these measures as well. According to Bill James, doyen of sabermetricians, Greenberg led American League first basemen in “Range Factor” in 1937. The idea that he was a mediocre fielder seems to have come from his relative lack of athleticism and a few high-profile errors he made after being forced to switch to the outfield late in his career. But Kurlansky’s larger problem is conceptual. Gumbrecht argues that thinking about sports has long been dominated by the concept of agon (competition), when we should be more focused on areté (virtue or striving for excellence). Greenberg has always been described as one of the hardest working baseball players, but this striving has tended to be held against him: he wasn’t “a natural.” “Ungraceful” may actually be the perfect way of describing Greenberg’s play, though not for the reasons his critics maintain. Theologically, grace is unearned. In sports, as Gumbrecht tells us, it “reminds us how we are sometimes unable . . . to associate the body movements we see with the intentions or thoughts who carry them out.” Greenberg’s approach, on the contrary, emphasized deliberation. He studied the pitcher’s tendencies and weaknesses in order to decide where and when to swing, even intentionaly chasing a ball outside the strike zone if it meant the possibility of driving in a run. While praising Ted Williams as his era’s greatest hitter, Greenberg criticized the Splendid Splinter’s narrow strike zone:

He had trained himself to make them give him his pitch before he’d swing. That’s great, but when . . . you’re the number four hitter or the number three hitter, you’re the boy they’re all leaning on and looking to carry them to victory. Sometimes you have to hit the ball whether you want to or not.

Greenberg understood his job as run production, and approached every at-bat with that goal. His ideal of athletic movement was subsuming the actions of his body to his mind. A new biography of Greenberg should use all the tools of modern statistics and historical research to describe more accurately who Greenberg was as a player, and why his style of play was compelling, possibly even beautiful. In the process, we might learn more about why this simple game has fascinated so many great Jewish American novelists and poets. If there is a Jewish Hank Greenberg story to tell, it is the story of first-generation success. Greenberg’s immigrant parents succesfully worked themselves into the middle class, and Hank continued the family’s upward trajectory: a boy from the Bronx who assimilated into the upper classes of American society through profesional achievement and, later, financial specualtion. Greenberg’s autobiography makes clear that he understood that baseball was a business early on. He played tennis and handball regularly as part of his conditioning at a time when players were more famous for carousing than training for peak performance. Greenberg hit 44 home runs and had a .977 On-Base Plus Slugging percentage when he was 35, an age when his All-Star contemporary Jimmy Foxx, another massive power-hitting first baseman, was all-but washed up. In short, Greenberg was a professional athlete years before sports required them. This professionalism extended to his financial dealings. He frequently held out for more money, not out of greed or petulance but because, in an era before free agency, it was the only viable negotiating tactic. He also requested deferred compensation, now a regular part of sports. In the final year of his career, he even negotiated a contract with the Pirates that gave him an ownership position in the team, with the guarantee that he could sell it back at the end of the season to benefit from the difference between income and capital gains taxes. Kurlansky and other biographers have a tendency to link Greenberg and Jackie Robinson, highlighting the adversity both of them faced (though, as Greenberg himself declared, there was no comparison). But the more important story is how aggressively he integrated the Cleveland Indians during his tenure as General Manager. This was entirely well motivated, but it was also good business. Premier athletes were going un-pursued because of prejudice, and Greenberg, like Branch Rickey before him, jumped on the market inefficiency. As with Rickey, Greenberg’s aggressive approach to the business of baseball was not without its downside. His acrimonious contract negotiations with Al Rosen (arguably the second best Jewish slugger of all time) ultimately drove Rosen into an early retirement. Greenberg’s athletic accomplishments gave him access to some of the most wealthy and successful Americans. He married Caral Gimbel, a department store heiress, and made influential friends. After his career as a baseball executive ended, Greenberg moved back to New York where he founded a small securities firm. Kurlansky sees Greenberg’s investment career as a hobby, something to keep him occupied between tennis and reading, when it was actually a thriving business. To his credit, Kurlansky gives Greenberg’s post-playing career more attention than do most biographers, but he treats it as a coda to the main Greenberg narrative rather than a continuation of his working life. Although we are arguably living in the golden age of Jewish American baseball players—Ryan Braun, Ian Kinsler, and Kevin Youkilis, among others—no Jewish hitter has yet reached the heights of Hank Greenberg, (His career totals would be even more impressive were it not for his military service in World War II.) Yale University Press’ decision to include Greenberg—and by implication, baseball—in its “Jewish Lives” series is admirable. Unfortunately, Kurlansky’s book is little more than an introduction to the facts of Greenberg’s remarkable life.

Suggested Reading

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

The 2,000-Year-Old Women

Michael Weingrad discusses how two of the most highly praised novels of 2018, Dara Horn’s Eternal Life and Sarah Perry’s Melmoth, feature a Jewish woman born in ancient Judea who still walks the earth today.

The Home Front

Eating very long breakfasts, lunches, and dinners with dozens of aging members of the Greatest Generation was the best part of Arkush's teaching experience.

Brother Daniel, Sister Ulitskaya

Ludmila Ulitskaya's fictionalized version of the Brother Daniel case asks us all to turn the other cheek.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In