The Great Family Circle

On January 23, 1924, the Jerusalem daily Do’ar Ha-yom ran an item about Esperanto. The newspaper’s editor, Itamar Ben-Avi, was the eldest son of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the fanatical Hebrew lexicographer. Ben-Avi founded Do’ar Ha-yom in 1919 as a livelier alternative to Ha’aretz, modeling it on the Daily Mail of London. After the death of Ben-Avi’s father in 1922, Do’ar Ha-yom honored him with a motto on its masthead: “Ben-Yehuda haya omer, ‘Daber Ivrit—v’hivreta.’” (Ben-Yehuda used to say, “Speak Hebrew—and get healthy.”) The slogan is a pun on the word Ivrit; the syntax confers rabbinic status—as in “Hillel haya omer”—and the message is a cardinal trope of Zionist discourse: The Jewish condition needs to be healed. The mantra remained on the masthead until Ben-Avi’s final day as editor. And yet, during his 14 years at the helm, the paper ran many pieces promoting Esperanto, the international language.

The little item from 1924 is dryly humorous: An anti-Semitic weekly in Germany had urged fellow anti-Semites to learn Esperanto, the better to communicate with anti-Semitic organizations in other countries. “The newspaper apparently forgot,” concludes the squib, “that the inventor of Esperanto was a Jew, the late Dr. Zamenhof.”

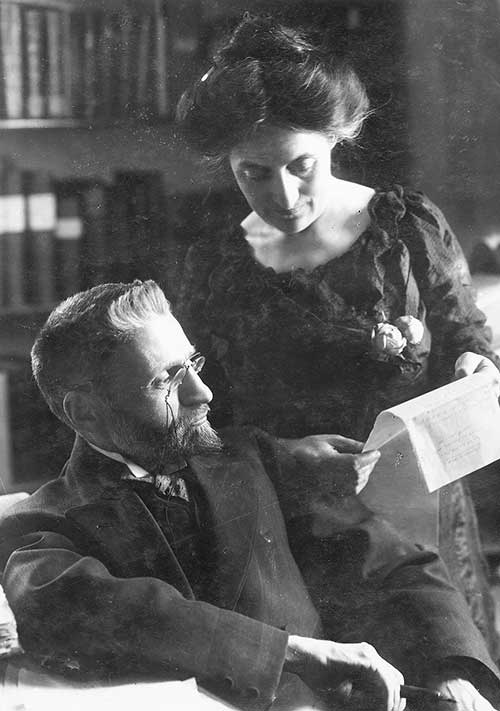

Well, obviously. The famous ophthalmologist Ludovik Lazarus Zamenhof was born in 1859 to a polyglot family of emancipated Jews, in the multi-ethnic city of Białystok, in northeastern Poland. His father, Markus, was a teacher, at one point a censor of Jewish newspapers for the tsarist regime. During his medical studies in Moscow and Warsaw, Zamenhof favored a nationalist solution to the perennial “Jewish question.” Settlement in Palestine was complicated by the claims of Muslims and Christians, so he floated the notion of a Jewish colony in America, on the banks of the Mississippi. Soon he switched gears and became a leader in the Hibbat Zion movement. Within a few years, he had lost faith in Zionism and turned his efforts to inventing a universal language that would eliminate misunderstanding and enmity in the world. With his “implausibly bulbous head” and “boxy beard,” as Esther Schor describes him in her wise and absorbing new book on Esperanto, Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language, the chain-smoking eye doctor “could have passed for a younger, less self-important brother of Sigmund Freud.”

Today, by a generous estimate, up to two million people speak Esperanto, maybe two thousand as a mother tongue. Streets are named for Zamenhof in many cities around the globe, including Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—where much bigger streets are named for Ben-Yehuda. Two Russian Jews, exact contemporaries, with noble, quixotic dreams of redemption through language—one vastly more successful than the other.

As a teenager, Zamenhof began experimenting with the notion of a universal language. He kept it under wraps during his Zionist period, working instead on a grammar of the Yiddish language and a system of writing Yiddish in Latin characters to extend its already considerable range among Jews. Ultimately, in 1887, under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto, Zamenhof self-published his inaugural pamphlet in Russian. Later known as the Unua Libro, the pamphlet explained the principles of the easily learned language and included translations into the lingvo internacia of a poem by Heine and the first 10 verses of Genesis. The tract was soon reprinted in German, Hebrew, Yiddish, English, and other languages. In 1888, he published a second brochure, this time in Esperanto itself. Here he announced that the language was now in the hands of its users, who should feel free to coin new words of their own. “It was as if,” writes Esther Schor, “God had stopped the Creation on the fifth day, trusting the animals to make the people.”

At first, Zamenhof assumed his project would appeal primarily to emancipated Jews like him. As he confided in a letter to Alfred Michaux, a French Jewish Esperantist: “My Jewishness has been the main reason why, from earliest childhood, I gave myself completely to one crucial idea, one dream—the dream of the unity of humankind.” As he saw it, the problem with Judaism, even among those who no longer observed Mosaic law, was an atavistic adherence to the covenant of chosenness. In 1901, he published a Russian-language tract called Hillelism, advocating a new, purified ethical Jewish creed, Hillelismo, predicated on Hillel’s dictum of loving one’s neighbor. Hillelismo recognized the existence of a “highest Power” that instills a moral conscience in the human heart. The language of this reinvented, universalized Judaism would not be a Jewish language, but a “neutral” one, free of nationalism: Esperanto.

As Zamenhof later told an interviewer from London’s Jewish Chronicle, “We ought to create in Judaism a normal sect,” which in time would “include the whole Jewish people.”

We should then become a powerful group. Nay, more, we should be in a position to conquer the civilized world with our ideas, as the Christians have hitherto succeeded in doing . . . Instead of being absorbed by the Christian world, we shall absorb them; for that is our mission, to spread among humanity the truth of monotheism and the principles of justice and fraternity.

But Esperanto didn’t catch on with Russian Jews. French intellectuals were more enthusiastic, but they had a problem: It was too Jewish. Indeed, some of the leading French Esperantists were anti-Dreyfusards, and Hillelismo, with its global ambitions, carried an aroma of Jewish conspiracy. Reluctantly, Zamenhof agreed to downplay his Jewishness and rebranded Hillelismo as Homaranismo (humanity-ism). In Schor’s words, he was “a chameleon, adept at surviving in diverse milieus by shaping his self-presentation to his audience.”

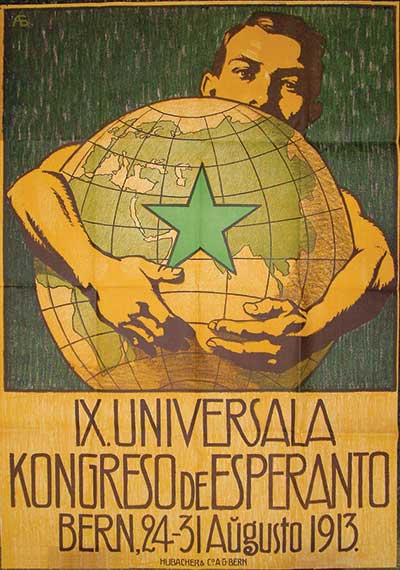

In 1905, at the movement’s first Universal Congress in Boulogne-sur-Mer, on the English Channel, the French organizers managed to obscure Zamenhof’s origins to such a degree that of 700 newspaper articles about the gathering, only one mentioned he was Jewish. By 1910, when Zamenhof made his only trip to America, the Washington Evening Star matter-of-factly called him “the enthusiastic Pole who invented Esperanto.” Thus, if the German anti-Semites cited in Do’ar Ha-yom were deaf to the irony of adopting Esperanto for their international needs, Zamenhof himself was to blame for fudging his identity.

One can imagine his pent-up anger. In June 1906, in his native Białystok, some two hundred Jews were killed in a pogrom. Later that year, in his address to the Second Esperanto Congress in Geneva—not once uttering the word “Jew”—Zamenhof let fly a graphic description of the carnage:

When still a child in the city of Białystok, I used to observe with sorrow the mutual distrust that separates sons of the same land, the same city. I used to dream then that after a few years this condition would change for the better. A number of years have gone by since then, but instead of my beautiful dreams I beheld a dreadful sequel. In the streets of my unhappy native city savage men with axes and crowbars were hurling themselves like the wildest of beasts upon the peaceful inhabitants, whose only crime was that they spoke a different language and had a different religion from those savages. And for that the latter broke the heads and gouged the eyes of men and women, of the decrepit old people and the helpless children! I do not wish to give you a detailed account of the unspeakable Białystok massacre. To you Esperantists I merely wish to say that the barriers between the nations are still appallingly high and thick, and it is these that we are laying siege to.

The founder made clear—to those who could hear it—what truly fueled his utopian agenda. Yet in the same speech he stressed the extreme pluralism of the Esperanto movement. “The Esperantists have decided to allow everyone absolute liberty to receive the inner idea [interna ideo] of Esperantism in whatever fashion and degree it may best please him; or, if he be so minded, he need not trouble about any idea at all.”

Zamenhof’s anxiety brings to mind Freud’s struggle to rid psychoanalysis of the stigma of “Jewish science.” In 1912, at the Universal Congress in Krakow, Zamenhof stepped down as leader of the movement. He also blocked a request by a Jewish Esperantist to salute the gathering in the name of the Jewish people. When the New York Yiddish paper Di Varhayt published a scathing critique, Zamenhof responded indignantly:

Every Esperantist in the world knows full well that I am a Jew, because I have never hidden the fact, although I do not shout it chauvinistically from the rooftops. Esperantists know that I have translated texts from the Yiddish language; they know that for more than three years I have devoted all my free time to translating the Bible from the Hebrew original; they know that I have always lived in an exclusively Jewish quarter of Warsaw (where many Jews are ashamed to live); they know that I have always had my works printed by a Jewish printer, etc. Are these the acts of someone who is ashamed of his origins and who is trying to hide his Jewishness?

Ever in need of money, the “enthusiastic Pole” worked long hours as an oculist to support his family and his activism. He migrated from town to town before settling in Warsaw in 1897, living in the same house, his office attached, for the rest of his life. He completed his translation of the Tanakh in 1914. He never quit smoking, and one surmises that the repression of his Jewishness also exacted a heavy toll. He died of heart failure at age 57, in 1917.

Esperanto was denounced by both Hitler and Stalin, but it was as Jews, not Esperantists, that all three of Zamenhof’s children were killed by the Nazis. Adam, the eldest, was shot near Warsaw. Zofia was deported to Treblinka. Lidia, born in 1904, extended her Esperantist universalism to an embrace of Baha’i. She journeyed to the Baha’i shrine in Haifa, taught Esperanto in France, and lectured in the United States. In 1938, when her American visa expired, she sought to return to Haifa, but her spiritual master, Shoghi Effendi, for reasons of his own, told her to return to Poland. She too, in September 1942, died in Treblinka.

Esther Schor is a poet and Princeton professor of English, and the author of Emma Lazarus (2006), a superb biography of the American poet and Sephardic blue blood, friend of Emerson, and writer of the passionate ode to immigration, “The New Colossus,” attached to the Statue of Liberty. Erudite and eloquent, fierce champion of her people, Emma Lazarus was a representative Jew to admire, indeed to emulate. Commenting on a Lazarus essay of 1884, Schor noted “an essential truth about her Judaism”:

[S]he saw no need to choose between Jewish universalism and Jewish nationalism. This is a principled, not incoherent, feature of her thinking, firmly in line with George Eliot’s view in “The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!” that the very impulse for nationalism was universal. . . . Taking a universalist view of patriotism, she likens Bar Kokhba to William of Orange, Mazzini, Garibaldi, Kossuth, and Washington.

In the present book, Schor proudly reclaims L. L. Zamenhof as a Jew, but this time she herself is the protagonist, inhabiting the tension between the particular and the universal. Toward the end, we find the author at an Esperantist community in rural Brazil. The co-founder, German-born Ursula Grattapaglia, asks what kind of book she is writing. Schor omits the Jewish angle:

“What kind of book?” I was stalling, and she knew it. “It’s a hybrid, history and memoir. It’s about Zamenhof, his language, his dreams, and the people he entrusted to build Esperanto, then and now. It’s about Esperanto as a bridge of words, and all the ‘internal ideas’ that have crossed it. And it’s about my wanderings in Esperantujo, the people I’ve met in Europe, Asia, California, here. . . .” I didn’t tell her it’s about me, too, though I never meant it to be; about how Esperanto helped me to navigate my middle-aged anguish, to get across what I needed to say.

Schor deftly builds a narrative, alternating chapters of travelogue with chapters of scholarship. She marshals a dazzling array of footnotes based on original Esperanto sources. She dwells at length on the history of the movement: acronym-splattered conferences, schismatic personalities, disputes over Esperanto grammar that undermine the founder’s ideal of brotherhood. This megillah will not captivate every reader, but it serves a strategic purpose. According to the Declaration of Boulogne, unanimously adopted at the First Congress in 1905, “an Esperantist is any person, without exception, who uses the Esperanto language regardless of the purpose for which he uses it.” Schor’s professional devotion to the lore of Esperanto qualifies her as a member of the club.

Along the way, the author demonstrates the niftiness of the invented language, its logic and simplicity, its ongoing evolution. Zamenhof based Esperanto on nine hundred roots, derived from various European languages. Prefixes and suffixes turn the roots into words. Manĝi = to eat; manĝaĵo = food. The prefix mal turns a word into its antonym: Maljuna = the elderly; malriĉa = the poor. In technical terms, as Schor explains, “it is an agglutinative language, like Japanese, Hungarian, and Navajo.” All verbs are regular, with no distinction between singular and plural. Questions begin with k—kial, kiam, kie, kio (why, when, where, what). Ingenious new words are coined as needed: bestkuracisto (veterinarian), huraistino (cheerleader, or “hurrah specialist”), memobastoneto (memory stick). At a three-week immersion course in San Diego, a fellow student invents a word for “Facebook”: visaĝlibro. It’s great fun. The most useful word in Esperanto slang is a no-no: krokodili, meaning “to speak one’s native language at an Esperanto gathering.”

Esperanto isn’t quite as easy as it looks, but anyone acquainted with the rudiments of Romance languages can figure out such sentences as Mi ne povas vivi sen vi (I can’t live without you). Longer texts are more challenging. Take, for instance, a statement by the Israeli Esperantist Naftali Zvi Maimon about Zamenhof’s hidden Jewish past: “Post la persekutoj kaj teruraj batoj kontraŭ sia gento dum la unua mondmilito li, ŝajnas, denove fariĝis cionisto.” With the help of digital translation, it all makes sense: “After the persecutions and terrible blows against his people during the First World War he, it seems, again became a Zionist” (though not, adds Maimon, an aktiva cionisto).

At the dawn of the movement, Zamenhof wrote a poem that was set to music and is still sung as an anthem at Esperanto gatherings. The penultimate stanza goes like this:

Sur neŭtrala lingva fundamento,

komprenante unu la alian,

la popoloj faros en konsento

unu grandan rondon familian.

Take a moment to decipher it. Swing from cognate to cognate, and it soon becomes clear: “On a neutral language basis, / understanding one another, / the people in agreement will make / one great family circle.” And the name of the anthem? “La Espero,” of course, “The Hope.” Hatikvah. Whether Zamenhof was acquainted with Naftali Herz Imber’s poem (originally titled “Tikvatenu”) is anyone’s guess. But the coincidence is, to use a Freudian term, overdetermined.

Schor’s travels supply a rich trove of anecdotes. In İznik, a Turkish town famed for ceramic tiles, she attends the Second Middle Eastern Conference of Esperantists: 35 participants from 17 countries. The proceedings, she writes, reflect “the movement’s revered tradition of political neutrality,” so there is no talk of Gaza or Iranian nukes. She gravitates toward the Israelis and learns about Esperantist activities during the British Mandate, which included meetings between Palestinian Jews and the Cairo-based Egipta Esperanto-Asocio (EEA). (Apparently, nobody mentions Itamar Ben-Avi.)

Next stop, Białystok, for a congress in 2009 in honor of Zamenhof’s 150th birthday. Restaurants in the city provide menus in Esperanto. There is a walking tour of Zamenhof sites, including a monument to the Great Synagogue that is no more. The guest of honor is the elderly Holocaust survivor L

ouis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof, known as “La Nepo” (the grandson), and revered by Esperantists as “something between a household god and a mascot.” Schor muses about “exuberant Esperanto gatherings” versus “dispiriting English Department meetings” at Princeton and hears a lecture about the Internet presence of Yiddish and Esperanto by Tsvi Sadan, an Orthodox professor of linguistics at Bar-Ilan who began life in Japan as Tsuguya Sasaki.

At the Universal Congress in Havana, the Cuban hosts throw parties with lively salsa bands and teenage assistants who “fan out onto the dance floor like bar mitzvah motivators.” Schor runs into a Dutch public-health professor she first met in Turkey; he takes her to meet veteran Esperantists in crumbling but picturesque Old Havana. Other attendees include a Chilean physician, a Croatian novelist, and a “wiry, ingratiating astrophysicist” who is head of the Israel Esperanto League. So it goes, in the universe of Esperanto:

Like Jews, Esperantists navigate among multiple identities at once, moving fluidly from their nuclear families to Esperantic circles to the workplace, and on to a world indifferent to matters of fraternity and harmony. I’ll confess that at Esperanto gatherings, I sometimes feel that I’m among meta-Jews; after all, Esperanto was invented by a Jew who renounced peoplehood, but couldn’t imagine a world without it.

When the author lands at the International Youth Conference in Hanoi, she learns the Esperanto word for jet lag: horzonozo, “time-zone-sickness.” The karaoke system at Hanoi University belts out “La Espero,” which “sounds like the Marseillaise arranged as a polka.” It turns out that Ho Chi Minh learned Esperanto in London during the First World War. (Another fun fact: The young Hungarian Esperantist George Soros defected to the UK during the Universal Congress in Bern in 1947.) Yes, there’s an Israeli on hand in Hanoi too, a young computer start-up guy who briefs her on Zamenhof’s Judaism: “I can tell it’s not really an interest of his, but you can’t be an Israeli Jewish Esperantist and not know all this. It would be like not knowing what a seder is.” And why is he an Esperantist? Because he—unlike most—still believes in the fina venko (the final victory), when the whole world will embrace Esperanto. “Till now,” writes Schor, “he’s sounded like a Starbucks-swilling Israeli hipster hanging out in Nepal. Now he sounds like his own bundist great-grandfather—or mine—patiently awaiting the final, inevitable triumph of socialism.”

But then, back in Princeton, there is a wrenching turn of events. Esther leaves Leo, her “bewildered, grieving” husband of nearly 30 years. Woven into her pages on Brazil, the last stop of her odyssey, is Schor’s poignant take on the interna ideo:

Zamenhof, the patriarch of a large Jewish family, built Esperanto on the foundation of family affections . . . Zamenhof’s vision for humanity was “one great family circle” because he deemed the family a fundamental source—even a guarantor—of fellow feeling among people of different religions, ethnicities, nationalities, and races.

For Esther Schor, Esperanto is a vehicle of self-discovery and healing. As her own family crumbles, she finds a new one that circles the globe. At the same time—inspired by Zamenhof—she insists on her individuality. Her epiphany arrives amid the Esperantist tribe in Białystok:

And for another thing, I’m a practicing, public Jew—not simply judadivena (of Jewish descent)—and when I hear condescension about particularism, I reach for my pistol. I wouldn’t still be wandering in Esperantujo if I believed that Zamenhof regarded Judaism with condescension or contempt; in my mind’s eye, while he “crosses the Rubicon” to universalism, he’s carrying Judaism on his back. . . . Which is all to say that here in Białystok, among these meta-Jews—this “great family circle” of Esperantists—I suddenly realize what I am: a meta-Esperantist Jew.

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda was born Eliezer Perlman in 1858 in the town of Luzhki, today in Belarus. Like Zamenhof, he was a Russian Jew who sought liberation through language. He too studied medicine, in Paris, and settled in Jerusalem in 1881. Many years later, in the introduction to his great dictionary, he recalled:

I found the answer, as simple and obvious as Columbus’s egg: Just as the Jews cannot truly be a living nation without a return to the land of their forefathers, so they cannot truly be a living nation without a return to the language of their forefathers, using it not just as a written language for religious and intellectual purposes . . . but as a spoken language . . . for all aspects of life, at all hours of day and night, just like all other people [k’chol ha-goyim], each in his own language [goy goy b’leshono]. That was the great, decisive moment in my life. Now I had discovered what I must do immediately.

Like Zamenhof, Ben-Yehuda felt an urgent need to invent a modern language of everyday life. He wanted to be normal (k’chol ha-goyim)—to neutralize otherness: It sounds downright Esperantist. But the project would necessitate a risky, traumatic experiment: to remake his baby boy into a New Jew, a native speaker of Hebrew. Born in Jerusalem in 1882, Ben-Zion Ben-Yehuda, later known as Itamar Ben-Avi, was shielded obsessively by his father from all other languages. A new edition of Ben-Avi’s memoirs, abridged and annotated, came out in Israel last year. Its engaging title says it all: He-hatzuf Ha-artziyisraeli: P’rakim Me-hayav shel Ha-yeled Ha-ivri Ha-rishon (The Cheeky Hebrew Man: Episodes in the Life of the First Hebrew Child).

“The birth of the first child in the home of the heretic Ben-Yehuda,” wrote Ben-Avi, “gave rise to strange rumors.” At the age of two, he had still not spoken; the father’s friends were alarmed. To revive Hebrew among adults was admirable, said Yehiel Michael Pines, “but to torment this poor child with Hebrew speech . . . there is no greater madness.” Children should speak the common languages of the Yishuv—“Yiddish or French, English, Italian, even German . . . so that people will understand what they are saying.” At this, wrote Ben-Avi, “my father leapt up as if bitten by a snake” and vehemently disagreed: “Yes, the experiment is difficult, but I will not give it up no matter what.” Pines rose to leave: “And what will you do if your son remains an idiot all his life? It would be a latter-day Akedat Yitzhak”—the binding of Isaac—“but no angel of God will come to his aid.”

At the Oedipal climax, the First Hebrew Child is three, still mute, and Ben-Yehuda is out of town. The anguished, homesick mother, Devorah, sings to him in Russian. Ben-Yehuda returns unexpectedly, catches her in the perfidious act, and smashes a table with his fist: “I will never forgive you, Devorah!” At which point, the frightened child exclaims: “Abba!” If that’s how Ben-Avi remembered the family drama, no wonder he was open to Esperanto.

In his memoir, the Cheeky Hebrew Man described several encounters at Jerusalem’s Kamenitz Hotel, apparently in 1911, with the Turkish army officer Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Ben-Avi floats the radical idea that a Jewish polity in Palestine, loyal to the Ottoman Empire, would adopt Hebrew in Latin letters, which, he contends, are closer to the original, biblical orthography:

And so, if you, sir, could do this in Turkey, and the Armenians to their complicated language, and the Arabs to theirs, and the Greeks to theirs—we will build a wonderful bridge to cross from nation to nation, a kind of Esperanto that is natural and not artificial.

The convivial evening draws to a close at 11, as a Turkish bugle blows in the distance. The two, who’ve been speaking French, part warmly: “Aux lettres latines pour l’hebreu!” Ben-Avi, as we know, is a good storyteller. All his life, he has been competing with a heroic, mythic father. He needs a myth of his own, an epic struggle. His father revived Hebrew; he will revolutionize it—universalize it, make it accessible to all Jews and Gentiles. And whereas his father was frail and tubercular, he will be the ultimate New Jew, one of those muscular, Canaanite types. He sorely needs that man-to-man moment with the mighty Kemal Atatürk, who borrows the great idea from him and goes on to change the typeface of Turkey. Did it really happen? (Scholars are skeptical.) Does it matter?

Ben-Avi is writing in New York exile, toward the end of his life, during World War II. He has created a few short-lived newspapers in Romanized Hebrew. One was called ha Şavuja ha Palestini (The Palestinian Week). In English, it said on the masthead: “Hebrew Sheet in Latin Characters.” Below that, in those characters: Esperanto ha Yahadut ha Jolamit (The Esperanto of World Jewry).

Ben-Avi sought to make life easier for the many Jewish newcomers to Palestine who found it difficult to master Hebrew writing. His pilot project was a biography of his father called Avi, published in 1927 in an intricate Latinized alphabet. On the very first page, Ben-Avi claimed he proposed his bold idea to Ben-Yehuda at the age of 10 and that his father encouraged him. In the article “Attempts at Romanizing the Hebrew Script and Their Failure” (Middle Eastern Studies, July 2007) the Turkish scholar İlker Aytürk tells us that most readers saw Avi as a betrayal of Ben-Yehuda, but Ben-Avi’s friend Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a staunch supporter of his efforts, read it differently:

You have done an important deed, sir, with this step of yours, a deed that will be remembered and that will have an impact. I do not say this as a compliment, nor as an exaggeration. . . . To show everyone, without explanation or apology, that indeed it is “possible”—and here is the book. So did Ben-Yehuda do in his time: Instead of discussing the “possibility” of a Hebrew family, he set about to create that family. You have, truly, followed in the footsteps of that great man with your deed.

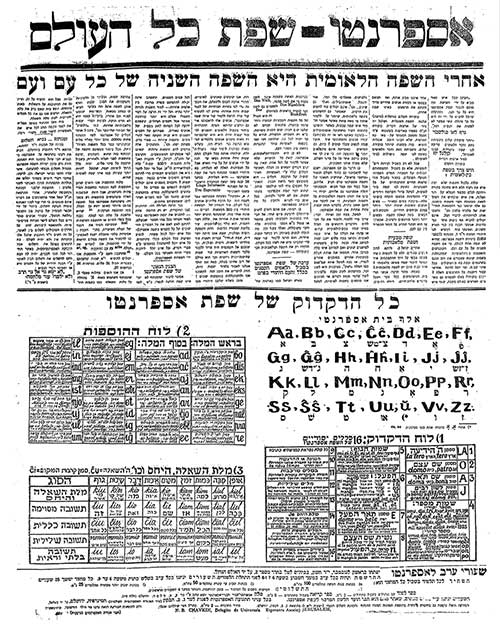

Ben-Avi went into the family business. Like his father, he coined many Hebrew words: alhut for wireless (i.e., radio), itonai for journalist, and yes, atzma’ut for independence. He argued that Romanization of both Hebrew and Arabic would facilitate Jewish-Arab coexistence in Palestine, in neighboring cantons. He ran a full page in Do’ar Ha-yom extolling the practicality of Esperanto, citing an endorsement by Tolstoy, and providing a chart for easy learning. It should be everyone’s second language, including Hebrew speakers, said Ben-Avi. He remained a Zionist patriot like his father and admired strong nationalist heroes, including Mussolini. But at the same time, like his father’s landsman Zamenhof, Ben-Avi strove to bridge the gap between Jews and the world.

In the end, his personal revolution didn’t stick. The indomitable mystique of Hebrew defeated the logic of Romanization. Ben-Avi, at the end of his memoir, reminds us that Hebrew is not a mere language: “Were it not for the divine holiness of this language, our diverse people, including the most extreme leftists, could not have accepted it completely.” On the penultimate page, the Cheeky Hebrew Child takes us by surprise: “I give thanks to God that it was my happy fate to be the guinea pig in the revival of the Hebrew language.”

As it happened, Ben-Yehuda had also penned his memoirs in America, during the First World War. The Turks were allied with Germany, and Ben-Yehuda feared for the future of the Yishuv and his own safety. As his son wrote in Avi, in Latin characters: “Ma yihyéh ’im yitpesûhu, ’im yé’esrûhu, ’im yaglûhu Anatôlyâtah?” (What would happen if he were caught and jailed, possibly deported to Anatolia?). The family was offered refuge in Manhattan by Jacob Wertheim, a wealthy cigar manufacturer whose son Maurice, the son-in-law of Henry Morgenthau, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, had visited Ben-Yehuda in Jerusalem. Maurice’s daughter, born in 1912, would grow up to become the historian Barbara Tuchman.

Ben-Yehuda and his second wife, Hemda—sister of Devorah, who had died of tuberculosis—lived on Central Park West with their daughters; Itamar Ben-Avi and his wife lived nearby. Ben-Yehuda worked on the dictionary, mainly at the New York Public Library, and, occasionally, at the Jewish Theological Seminary. The Israeli scholar Yosef Lang, in his exhaustive, two-volume biography of Ben-Yehuda, Daber Ivrit! (Speak Hebrew!), wrote that a summer home at Elberon, on the Jersey Shore, was also made available to the great man, and it was there, of all pleasant, exilic places, that he worked on his autobiographical writings. His touching memoir Ha-halom Ve-shivro, serialized in the New York Hebrew weekly Ha-toren in 1917–1918, concludes with a somewhat rueful account of his draconian isolation of his eldest child, which placed a terrible burden on his beloved Devorah. In literary Hebrew, the title translates as “The Dream and its Interpretation,” which might be construed as an homage to Freud.

As he mingled with American benefactors and well-wishers, the irony of exile must have driven Ben-Yehuda nuts. Over the years, he had written many articles arguing for shlilat ha-galut (negation of the diaspora). Indeed, Ben-Yehuda went so far as to tell his young daughters—I heard this from Dola, whom I met in 1989—that he would rather they marry a non-Jew, live in Eretz Yisrael, and speak Hebrew, than marry an American Jew, live in New York, and speak English. Like Zamenhof, he was ready for Jews to absorb the nations of the world—but only in the Hebrew homeland.

Dola Ben-Yehuda married Max Wittmann, a non-Jewish German who lived in Mandatory Palestine. They spoke Hebrew at home in Jerusalem, and had no children. Max died in 1991 and was buried in the Christian cemetery on Emek Refaim Street, in the German Colony. Dola died in 2004 at age 102, having willed her body to the Hebrew University for research. Several years later, her remains were interred in Max’s grave, closing the family circle. At the modest, unpublicized ceremony, university officials and other observers were fairly startled when a young Israeli descendant of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a pupil at a religious high school, chanted the El Maleh Rahamim, gently praying in a Gentile graveyard for the souls of Doda Dola ve-ha-dod Maxie.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Nation of Israel?

The case for an Israeli—not Jewish—republic.

Letters, Spring 2023

Cliff-Hangers When I first read Hillel Halkin’s assertion in “On That Distant Day” (Winter 2023) that “for years now, Israel has seemed to me like a man sleepwalking toward a cliff” and “now we’ve fallen from it,” I thought it was excessive, though I shared his concerns about the Likud’s coalition partners (Zionist theocrats, anti-Zionist free-riders). Writing now, in the…

Sincere Irony

In a new book about religious moderation, William Egginton makes some good points, along with a few immoderate claims.

The Rise of Hank Greenberg

On Rosh Hashana, Greenberg went to shul, then the ballpark and hit two home runs. "Hank’s Homers are strictly Kosher," said the Detroit Free Press.

gwhepner

THE HOPELESS ESPERANTO OF OBAMA AND GEORGE SOROS'S FATHER

Bel pensanting in the belly of the beast,

hopefully, with liberal bel canto,

Obama tripped the light fantastic, an artiste

who performed in hopeless Esperanto.

A novel in this language by the father of George Soros,

who far less money than his rich son generated,

he like Obama causes Zionists great tsoros,

and for his money, not his hopeful words, is venerated.

With a language Zamenhof attempted to unite

the people of the world who don't feel universal,

while George Soros with his money tries to fight the right,

attempting to inflict on Israel a reversal.

The people of the universe are not are not united and

the state of Israel despite Soros has more power

than it's ever had, for like all nations Jews demand

a land and language of their own where they can flower.

[email protected]

Joe Magnoli

La Espero (Hope)

En la mondon venis nova sento,

tra la mondo iras forta voko,

per flugiloj de facila vento

nun de loko flugu ghi al loko.

Ne al glavo sangon soifanta

ghi la homan tiras familion:

al la mond' eterne militanta

ghi promesas sanktan harmonion.

Sub la sankta signo de l'espero

kolektighas pacaj batalantoj,

kaj rapide kreskas l'afero

per laboro de la esperantoj.

Forte staras muroj de miljaroj

inter la popoloj dividitaj,

sed dissaltos la obstinaj baroj,

per la sankta amo disbatitaj.

Sur neŭtrala lingva fundamento,

komprenante unu l'alian,

la popoloj faros en konsento,

unu grandan rondon familian.

Nia diligenta kolegaro

en laboro paca ne lacighos,

ghis la bela songho de l'homaro

por eterna ben' efektivighos.

~ Doktoro Zamenhof'