The Rebbe and the Yak

During the High Holiday season in Bnei Brak, a city of tzaddikim (saintly rabbis) and their followers near Tel Aviv, the Ustiler Rebbe has a vivid and disturbing dream. A large buffalo-like animal stands against a backdrop of snow-capped mountains, and speaks to him. It is the voice of his ancestor and namesake Yaakov Yitzchak, known to (actual) history simply as the “Holy Jew” (Ha-yehudi ha-Kadosh), an 18 th-century Hasidic figure of extraordinary spiritual integrity. The animal, or at least its voice, beseeches the Rebbe to rescue him. Ignorant of geography and zoology, the Rebbe consults with more worldly advisers, who identify the animal as a yak and the locale as Tibet.

The dream comes to the Rebbe three times, convincing him that it is truly a message from heaven rather than a trick of the unconscious. His great ancestor has, for some reason, been trapped in the body of a yak through the process of gilgul, the transmigration of souls. With the help of one of his followers, a wealthy Antwerp diamond dealer, the Rebbe secretly disappears from his court during the fraught weeks before Rosh Hashanah, flies from Tel Aviv to Beijing and then on to Lhasa, finally taking a Land Rover to remote monasteries in search of the famous wild Golden Yak and the soul of the Hasidic master imprisoned within it.

This is the premise of Haim Be’er’s latest novel, El makom sheha-ruah holekh, in English literally translated as “to a place where the wind (or spirit) goes,” though the Israeli publisher’s suggested English title is Back from Heavenly Lake. Be’er’s novel is as funny as its premise is preposterous, but the protagonist turns out to be a man with a complex inner spiritual life rather than the farcical Hasidic stick figure one might expect. Moreover, the language of the novel is suffused with antic echoes of sacred texts in a way that makes it a pleasure for any Hebrew reader with a modicum of Jewish literacy. That Be’er can pull all of this off makes him a unique figure in the landscape of today’s Israeli literature, in which religious themes are usually regarded as fruit of the poisonous tree. He is one of the few Israeli writers or public intellectuals who draw upon a wide range of traditional Jewish sources while still managing to gain the attention and admiration of a serious reading public that is preponderantly located on the secular side of a deeply divided national culture.

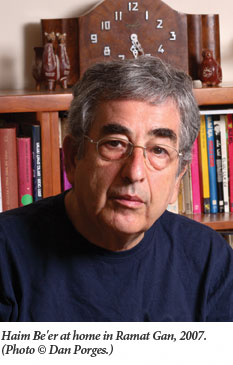

Born in 1945, Be’er used his own childhood on the outskirts of the old Orthodox neighborhoods of Jerusalem as the scaffolding for his early novels, while characteristically deflecting the focus from himself in favor of a gallery of colorful and eccentric characters whose lives could not be imagined in the pages of any other Israeli writer. Thus, at the center of Be’er’s first novel Notsot (published in 1979 and translated as Feathers by Hillel Halkin in 2004), stands Mordecai, a childhood friend who is obsessed with creating a Nutrition Army that would establish a vegetarian state honoring the principles of Josef Popper-Lynkeus, a 19th-century Austrian Jewish utopian thinker. Havalim (published in 1998 and translated by Barbara Harshav as The Pure Element of Time in 2003), Be’er’s most richly realized work, is a nuanced account of the author’s family, including a pious, storytelling grandmother; a smart and independent mother who descended from the rationalist, anti-Hasidic stock of the Old Yishuv community in Jerusalem; and a passive father, a refugee from Russian pogroms, who loved synagogue life and cantorial music. Be’er’s account of how he found his way to becoming a writer amidst these strong influences bears comparison to Amos Oz’s more famous account of his parents’ tangled lives in A Tale of Love and Darkness. Amos Klausner (later Oz) and Haim Rachlevsky (later Be’er) in fact grew up in nearly the same neighborhood in Jerusalem. As it happens, years later Be’er succeeded Oz as a professor of literature and creative writing at Ben-Gurion University.

Be’er extends his reach in his new, Hasidic-Tibetan novel by doing something unique in Israeli literature: examining the inner life of an ultra-Orthodox rabbi. The novel’s great accomplishment is Be’er’s ability to do this in a way that is at once satirical and serious. Here is a passage that demonstrates something of Be’er’s capacity to operate in both modes at the same time. The Rebbe is in Beijing on his way to Tibet with Simcha Danziger, the diamond magnate who has underwritten the trip. The two men are studying the weekly Torah portion, which happens to be Ki Tetse (Deut. 21:10-25:19), the beginning of which deals with the case of a Gentile woman captured in war. Meanwhile, Danziger has noticed, with alarm, his spiritual leader’s keen interest in Dr. Selena Bernard, the beautiful zoologist who is accompanying them.

“Keep in mind, Simchele, that hidden in every transgression is a divine element. One who is engaged in worldly affairs—and who would know this better than you?—needs to conquer the sin in order to redeem the captive imprisoned within it. This captive,” the Tzaddik of Ustil continued to teach Simchele, “is the very same ‘beautiful woman’ described in the Torah portion. A man sees her in her captivity, desires to take her as a wife, and brings her into his house.”

On the one hand, the Rebbe makes a typically Hasidic interpretive move by spiritualizing the biblical text and making it an allegory for the inner life of the believer. On the other hand, he is simultaneously distracting his follower from his questionable behavior and rationalizing his conspicuous attraction to the lovely zoologist, with whom he does indeed fall in love as the story progresses. Is this a depiction of rabbinic hypocrisy in the best traditions of Enlightenment satire? Or is there a genuine lesson being taught about the need for religion to be fully engaged with and exposed to the world? Be’er manages to keep both ideas in play. In fact, this is a novel in which Be’er always has several balls in the air at once, and the good news is that despite the absurdity of its premise, it is both funny and affecting.

There are three very different genres of narrative that overlap and bump up against one another in this novel, and this jostling creates both brilliant effects and occasional confusion. It remains one of the most thought-provoking facts of modern Jewish history that the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) and Hasidism both arose at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, often in exactly the same regions of Eastern Europe. Back from Heavenly Lake is, at one level, a return to the anti-Hasidic satires of the proponents of the Haskalah, known as maskilim. A tiny minority compared to the Hasidim, the maskilim made the barbed arrows of satire their weapon of choice. Enlightened satirists like Josef Perl and S. Y. Abramovich (who went by the pseudonym Mendele Moykher Seforim) wickedly appropriated the very language in which their subjects thought and spoke, while leaving their readers to savor its absurdity. The novel’s epigraph is taken from Abramovitch’s The Travels of Benjamin the Third, a hilarious tale of a shtetl Jew who embarks on a grand quest but ends up only a few towns away. With the same wink and nod, Be’er lets the chicanery and sanctimony at the heart of the Bnei Brak court of the Ustiler speak for themselves.

In order to find a niche among the fiercely competing tzaddikim of Bnei Brak, the Ustiler’s advisors and his wife Goldie have conspired to exploit the Rebbe’s intuitive wisdom. He is presented to the public with the grandiloquent moniker—in talmudic Aramaic no less—as Ha-tsintara De-dehava (the Golden Catheter) who can penetrate people’s hearts. The listening devices hidden in the anteroom to the Rebbe’s study provide a useful assist in helping the Rebbe deliver his oracular counsel to Jews from all walks of life who seek his advice and then contribute in gratitude to his coffers. As the Ustiler’s fame spreads, his handlers position him to be an Ashkenazi equivalent of such illustrious Moroccan holy men as the famous Baba Sali and his successors.

Alongside this satire lies a compelling realist narrative. Here is a man who is trapped—perhaps like his ancestor in the yak—inside an unhappy arranged marriage to the member of another famous Hasidic family. Goldie is a schemer who makes extra cash by smuggling diamonds into the US. Their three sons are devoid of learning or spirit, and the Rebbe’s whole entourage is dependent on his willingness to continue playing the role of the wonder-working tzaddik. Although he sincerely believes in the heavenly origin of his strange dreams, it is evident to the reader that the Ustiler’s mission to Tibet is a desperate if unconscious strategy to find a way out of his situation.

Even if the very existence of a figure like the Ustiler is just barely credible, Be’er does a good job of imagining what it would be like for a man who has never entered a theater or read a secular book or had a female colleague to encounter the outside world for the first time:

He had never spent time in the company of a woman who spoke to him as an equal. The only women he knew were the mortified women who thronged his inner sanctum to pour out their troubles in hurried tones and with downcast eyes or the women in his family circle, whose words were outwardly modest and pious but inwardly empty, and this is not to mention Goldie, whose speech when they were first married was a kind of fake simpering, which with time became saturated with bitterness, resentment, and disappointment.

So when he meets Dr. Selena Bernard, the beautiful expert on high-altitude fauna who speaks to him simply and directly as a person, he falls hard. Yet although Selena is both impressive and desirable, the ease with which Be’er’s sheltered tzaddik jumps into their love affair seems ludicrous and works against the novelistic credibility Be’er has been storing up.

The novel’s most dazzling and credible creation is Simcha Danziger. Be’er has a sharp eye for the curious but real way in which fawning, abject piety can be combined with business savvy in the ultra-Orthodox world. Danziger holds his Rebbe’s wisdom in high regard and readily submits to his moral instruction. Yet the lessons his Rebbe teaches almost invariably contain a humanistic twist beneath their holy garb. While the two men are observing a religious procession in Tibet, for example, one of the marchers stumbles and the religious figurine he is holding aloft almost crashes to the ground. Danziger, who is repulsed by such “idol worship,” hastens to quote a famous verse in Psalms: “They have mouths, but cannot speak, eyes but cannot see . . . they have hands, but cannot touch, feet but cannot walk.” But the Ustiler fires back with Proverbs: “If your enemy falls, do not exult; if he trips, let your heart not rejoice.” Behind his scriptural rebuke is more than good manners; he is genuinely open to the world in the way that the worldly businessman’s piety cannot allow.

The third narrative layer of the novel is the story of the Rebbe’s spiritual search. Despite his complicity in his own merchandising, the Ustiler possesses a genuine religious sensibility and a profound knowledge of both rabbinic and Hasidic literature. He understands his present dilemma as a belated version of his ancestor’s quest for authenticity. His saintly ancestor, whose soul is now apparently trapped in a yak, was a student of the famed “Seer of Lublin.” In time, the disciple took issue with the master’s desire to popularize the message of Hasidism. The “Holy Jew,” as he came to be known, established his own court in Pshiskha, where he led a small number of chosen disciples in striving to unify ecstatic prayer with Torah study. His teachings were carried forward by his disciple, Menachem Mendel of Kotsk, who ridiculed wonder-working rabbis. The conflict between the Seer of Lublin and his erstwhile student is the subject of Martin Buber’s novel Gog and Magog. Selena brings a copy of Buber’s novel with her on the trip and finds that the Ustiler has ironically—but entirely plausibly—never heard of it, even though his native humanism makes him sound at times like a Buberian Hasidic master.

The Ustiler Rebbe is seeking not only an elusive yak, but to extricate himself from his soul-crushing predicament in the contemporary world of Israeli Hasidism, and to find a purer path. As a place of genuine if sometimes frightening spirituality, Tibet serves as a foil for Israeli society, where a majority of the population has tragically alienated itself from the resources of its religious tradition, while a minority has turned religion into a prideful hieratic cult. But the contrast is, unfortunately, not really explored. There is a failure of nerve, or at the very least, a conceptual fuzziness, when it comes to parsing the religious moments of the novel. The Ustiler does finally succeed in finding the holy Golden Yak by the “heavenly lake” of the book’s title, but whatever Gnostic enlightenment he may have received in the encounter is lost in the fatal breakdown or injury—it’s never clear—he incurs at that very moment. The yak itself, and the captive soul it contains, remain a mystery.

Be’er has taken a big chance in attempting to combine three different literary modes in one novel, but his gamble pays off only in part. There are moments when we are buoyed aloft by the carnivalesque experience of Back from Heavenly Lake, and then there are others when the rapid switching back and forth among these modes leaves us disoriented.

Where this antic, overdetermined quality works to Be’er’s best advantage is in his language, which might be the novel’s true hero. The best Israeli authors today write in a literary Hebrew that is the culmination of a cultural smelting process that has been going on for at least the last century and a half. The religious meaning of words taken from classical sources has been leeched out to fashion a secular literary Hebrew, which can then be mixed with the natural speech that has arisen organically from a living society. It is a powerful hybrid medium that has created exceptional literature. Yet reading Be’er makes us realize, heartbreakingly at times, how much has been given up to achieve this goal. Be’er himself uses the standard style adroitly and has a fine ear for slangy dialogue, but he also has at his disposal the daily prayers, the weekly portion, chestnuts from Psalms and Proverbs, the lives of the talmudic sages, the visions of the kabbalists, and, of course, the tales of the Hasidim. His Hebrew breathes of presence rather than absence. He blends these materials together like a joyous organ master who delights in the resources of his complex and magnificent instrument. In this, he can only be compared to his great predecessor S.Y. Agnon. Other writers of Be’er’s generation have tried to integrate traditional materials, but their efforts often leave an aftertaste of sanctimony and entitlement. One hopes that the adroitness with which Be’er brings all of these elements together will serve as an inspiration for the next generation of Israeli writers.

It is perhaps only at the level of language, as in Be’er’s masterful orchestration of Hebrew’s many modes, that the contradictions of Israeli culture can be drawn together. If so, then it is not mere escapism to dwell in Be’er’s world but a kind of positive duty to be performed with delight. Just as the rabbis positioned the Sabbath as a foretaste of the World to Come, reading Be’er’s multivalent novel sustains a larger vision of what the Jewish people could be. Despite the very steep challenges of translation, may the tale of the Ustiler and the Golden Yak soon have the good fortune of being available to English readers as well.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The First Lady of Zionism

At the age when most of us are just about to fold our tents, Henrietta Szold, pitched hers—and in the Holy Land, no less.

Chasing Death

The director of the landmark documentary Shoah, Claude Lanzmann, has written a memoir, which sheds new light on his death-defying life.

Necessary Power: A Rejoinder to Jonathan Sacks

When Rabbi Sacks writes, “It is not our task” (and it was not Abraham’s task) “to conquer or convert the world or to enforce uniformity of belief. It is our task to be a blessing to the world. The use of religion for political ends is not righteousness but idolatry,” it seems to me that he oversimplifies matters.

The Jewish Preview of Books—September 2018

A quick look at Jewish books being published this month.

noam.zion

Terrific review, Alan, it makes the nonHebrew reader sad to miss the richest aspect of this new novel. I wonder if Be'er's youthful infatuation with Canaanite Movement has a place in this new novel.