Tough Bananas

Readers of Rich Cohen’s 2009 book Israel Is Real: An Obsessive Quest to Understand the Jewish Nation and Its History may remember Sam Zemurray, the man who took United Fruit to its apogee. Zemurray, Cohen tells us, took a break from running a global behemoth to aid in the founding of the state of Israel, first reducing his duties at the firm two months before the UN vote on the partition of Palestine, then resigning for “personal reasons” less than a week before Israeli statehood was declared. He didn’t return to work until June 1949, when the armistice that ended the War of Independence was signed. During this hiatus, he procured boats for the Bricha, the illegal transport of Jews from the DP camps of postwar Europe to Palestine. (Although Cohen can’t prove it to a certainty, strong evidence points to one of the ships, a former United Fruit freighter, being the Exodus.) Cohen also compellingly argues that in 1947 Zemurray persuaded countries that had no strategic links to the Middle East but where United Fruit owned vast tracts of land—countries such as Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua—to vote in favor of partitioning Palestine. In total, eleven Latin American countries voted in favor.

In The Fish that Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King, Cohen continues to explore an archetype that clearly fascinates him. For Cohen, as he writes about his father in Tough Jews: Fathers, Sons, and Gangster Dreams, “It’s all about Jews acting in ways other than Jews are supposed to act, Jews leaving the world of their heads to thrive in a physical world, a world of sense, of smell, of grit, of strength, of courage, of pain.” No pencil pusher, no mystic with his nose buried in a sefer, Zemurray labored in the fields, swinging a machete, killing snakes, crossing Honduras on the back of a mule that threw him to the ground, bit him, and dropped him in the middle of a river.

Like the Zionists and Israeli sabras who Cohen views with something so close to awe as to be indistinguishable from the real thing, Zemurray “believed in the transcendent power of physical labor.” For Cohen, it’s also about sticking it to the goyim, to the people who turned up their noses at Zemurray in corporate boardrooms, to the people who refused to sell him a home in Boston when he was at the helm of United Fruit, who saw him as a Jew rather than a corporate titan.

Cohen is masterful at describing how Sam Zemurray built his empire, starting from his days as a travelling vendor selling bananas too ripe for most sellers to bother with—making real money from something the experienced banana

merchants saw as a loss, an end-of-the-quarter write-off. Within a few years, he had enough credibility that he was able to borrow money to start his own plantation, the beginnings of Cuyamel Fruit.

Zemurray bought his first parcel of land on the edge of Omoa, an old colonial town on the north coast of Honduras. Much of the property ran along the southern bank of the Cuyamel River, where the country is hilly and fine, a thousand shades of green. This was long considered junk land, neither valued nor tended. For $2,000, all of it borrowed, he got five thousand acres. He was soon back in New Orleans, wondering if five thousand was enough. Would it give him the supply he needed to compete with United Fruit? It does not matter if you think it’s enough, [his partner] Ashbell Hubbard told him. We’re out of money. There are times when certain cards sit unclaimed in the common pile, when certain properties become available that will never be available again. A good business feels these moments like a fall in the barometric pressure. A great businessman is dumb enough to act on them even when he can’t afford to.

His partner cracked under the pressure, selling his share to Sam, while Zemurray borrowed from anyone who was lending, rolling every dollar he could find into expanding his land holdings.

In 1933, Zemurray staged a hostile takeover of United Fruit, which had earlier purchased his Cuyamel Fruit company and sent him into early retirement. In the years after the Cuyamel buyout, United Fruit’s stock price plummeted and with it Zemurray’s net worth, which dropped from $30 million to less than $3 million (this in 1932 when a million dollars really bought something). Adding insult to financial injury, United Fruit’s board of directors, old-money Gentile blue bloods, ignored Zemurray’s sage advice on how to turn the business around. At a board of directors meeting in January 1933, Cohen reports, Zemurray spoke again, advising, instructing, sharing the knowledge gained from years of work, literally hands deep in the dirt of the plantations. He was summarily waved off by chairman of the board Daniel Gould Wing, he of the impeccable lineage and cushy job as president of a Boston bank. Mocking Zemurray’s “thick Russian accent,” Wing waited for Sam the Banana Man to finish, “smiled and said, ‘Unfortunately Mr. Zemurray, I can’t understand a word of what you say,'” bringing the other men at the table to laughter. In a moment surely cherished by Cohen, who idolizes Jews who offer (as he once described the 12th-century false messiah David Alroy) “a picture of strength to a people lousy with weakness,” Zemurray slapped a bag filled with enough voting proxies to give him control of the company on the table and said, “You’re fired! Can you understand that, Mr. Chairman?” In that moment, Zemurray became the fish that swallowed the whale.

Along the way, you learn, as you do in all of Cohen’s books, some interesting fact that can be trotted to amaze the kids or fill awkward lulls in conversation: Banana trees (which aren’t really trees, but grass) grow so fast that you can actually hear them growing, shooting up as much as 20 inches in 24 hours. Because they’re grown from a cutting of a rhizome, every single banana (which is a berry) is a clone of every banana of its species, which makes them particularly vulnerable to disease. A pest that can kill one banana plant can kill every banana plant of its kind. Banana plants can grow in many places, but other than the tropics, the only two places where they will bear fruit are on the slopes of Icelandic volcanoes and in Israel “for reasons that remain mysterious.”

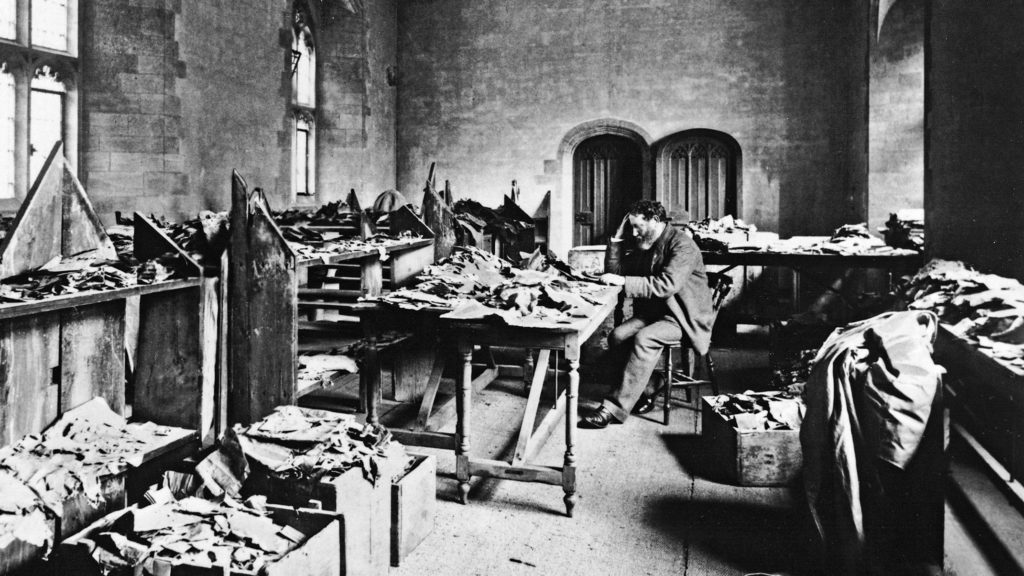

Cohen is an impressive researcher and a lively writer. What he does with those gifts at times, however, reveals as much about Cohen as it does about his subjects. Preparing to write Tough Jews, he pored through the archives of Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office, reading maps of getaway routes and handling ropes that strangled informants. Cohen’s gangsters are vividly rendered, fully fleshed individuals. The hands that twisted the rope around a man’s neck are in living color, but the neck and the dead man attached to it are, in Cohen’s prose both figuratively and literally lifeless. Zemurray could be as ruthless as a gangster. When his father-in-law Jake Weinberger came out of retirement and started a small business selling bananas in markets Zemurray serviced, the ties of family meant nothing. Cohen relays the following exchange with relish:

“Look, Jake, I want you out of business. I’m going to give you money so you’ll be just fine, but I don’t want you fooling with price. I want to set the price.” Jake said, “I’m not going to give it up. I’m making money.” Sam said, “Well Jake, either you get out or I’m going to cut my price and drive you out and you’ll be ruined.”

Zemurray’s bribing of corrupt officials to avoid paying taxes and staging coups in Honduras and Guatemala to overthrow governments that refused to stay bought are similarly retold by Cohen as exciting adventures.

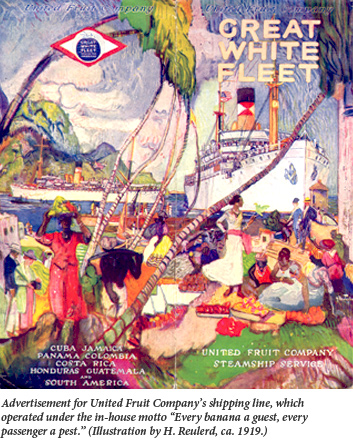

The men who labored in the fields and on the ships for Zemurray are close to invisible in Cohen’s book, a page here, a paragraph there. His tone remains light even when relating how Zemurray’s field workers, spraying chemicals to beat back a fungus attacking the bananas, lose their sense of smell and taste then waste away to nothing (though not before their skin turns blue, earning them the nickname “los pericos,” Spanish for parakeets). Cohen acknowledges the “cruelty and racism” of a banana colony as a fact, but a fact of much less import and interest than how Zemurray modernized United Fruit and made the banana ubiquitous.

The Fish that Ate the Whale is, in truth, a rollicking good story, a Horatio Alger tale writ large, and with a tough Jew as the hero to boot. Zemurray is quoted everywhere as having said of his business expenses that “a mule costs more than a deputy.” But Cohen warns us not to take these words as “callous indifference,” or “contempt for life,” or “the sort of corruption that borders on evil.” Instead we should, like Zemurray, look at the bottom line. As Cohen notes, “If a man wanted to do business in Nicaragua, there were certain things he had to buy—these included banana mules and police deputies. When balancing the books, you could not miss the fact: a mule did indeed cost more than a deputy.”

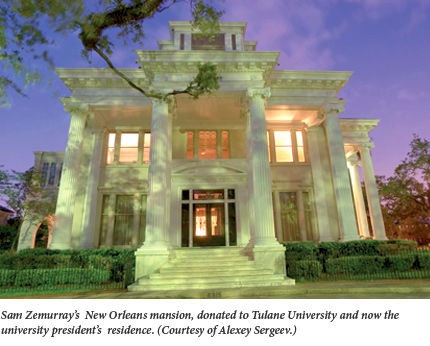

“Every story needs a villain,” writes Cohen. Zemurray has played the villain in many books about United Fruit and Central America. But Zemurray also helped Ben-Gurion found a nation and worked hard so his wife and children would have enough money to live in the comfort he had not known as a poor immigrant. He donated his New Orleans home to Tulane University—Cohen’s alma mater—a showpiece that is today the residence of Tulane’s president. During World War II Zemurray, whose only son was killed in uniform, turned banana lands over for the cultivating of plants that would yield hemp rope for warships, antimalarial pills for troops in the Pacific theatre, and rubber that would allow tanks to roll and soldiers to march on sturdy-soled boots. Quietly, without fanfare, he gave millions of dollars in philanthropic gifts, endowing medical facilities for the poor of New Orleans; building hospitals, orphanages, schools, and infrastructure projects in Central America; and gifting half a million to the Jewish Agency in the 1920s and $700,000 to build a power station in the Yishuv. In Cohen’s account, the villain is the whale, United Fruit: El Pulpo (the octopus), not Zemurray’s plucky little fish, Cuyamel Fruit, the Goliath to Zemurray’s David.

Suggested Reading

Buried Treasure

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish manuscripts were redeemed from Egypt.

A Certain Late Discovery

Was Jacques Derrida a Jewish thinker?

I Have Come to My Garden

Without the Torah, says Rabbi Akiva, we would still be able to discover all its truths by delving deeply into the words of the Song of Songs.

A “New History” and Old Facts

Fifty years after the conflict, Guy Laron’s The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East attempts to upend our understanding of the hostilities.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In