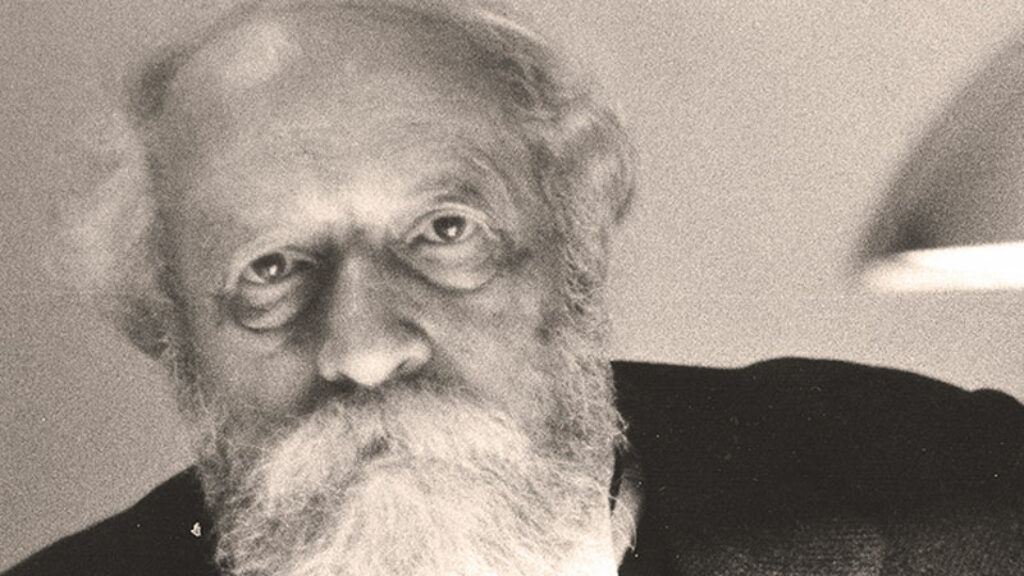

Yehuda Amichai: At Play in the Fields of Verse

Yehuda Amichai was an exuberant person with a lively, impish sense of humor. He was, at the same time, a melancholy man. Perhaps the note of melancholy, accompanied by a certain hint of fatigue, became more pronounced in his later years, but Amichai’s sense of fun never entirely left him. Both traits of his personality are present in his poetry in shifting combinations and permutations, with the playfulness actually feeding into the darker brooding of his poems.

Amichai’s playfulness is most spectacularly evident in his use of figurative language. He did not, as far as I can tell, have a fixed aesthetic program for using a particular kind of imagery. Rather, his imagination reveled in seizing possibilities for metaphor from unlikely directions (he was similarly inventive in conversation). Amichai’s characteristic move was to light on some familiar object and, in a quick gesture, usually not felt as a conceit, use it to focus an emotion or even serve as a gateway for vision: “Longing is shut up inside me like air bubbles / in a loaf of bread.” “My girl left her love on the sidewalk / like a bicycle. All night long outside and in the dew.” “For my heart has lifted weights of pain / in the terrible competitions.” “I see you taking something from the fridge, / lit up from within it in the light from another world.” Ordinary material objects sometimes take on a wild life of their own: “All night long your empty shoes screamed / by the side of your bed.” There are constant crisscrossings between emotion or abstraction and materiality, as in “A will like the fingers of a cast-off glove.” This frequently leads to a flamboyant syntactic bracketing together of terms from disparate semantic realms. This device is nowhere more insistently and extravagantly used than in the brilliant long autobiographical poem, “The Travels of the Last Benjamin of Tudela.” Here is a brief representative instance:

Echoing and hollowing Rosh Hashanah halls

and Yom Kippur machines of bright metal,

prayer-gears, an assembly line of bowing and prostration

in a melancholy mumble.

As this quick sampling suggests, the athletic play of Amichai’s figurative imagination is evident even in translation. But the idea sometimes voiced that he is an easily translatable poet, perhaps almost as good in English as in Hebrew, is profoundly misconceived. He had an acutely sensitive ear to the distinctive resonances of the Hebrew words he used, the deep backgrounds of allusion they evoked, and the significant shifts of register they enabled.

In the serious play of Amichai’s poetry sound begets like sound, leading to surprising and meaningful matches between words one might have thought were unrelated and creating startling new perceptions of things. Sound-play of one sort or another is of course an intrinsic feature of most poetry, but its spectacular centrality in Amichai is noteworthy. Let me illustrate from “The Visit of the Queen of Sheba,” a poem in eight parts from his second volume of verse that is one of his most inventively exuberant creations. Here are the first five and a half lines of the sixth poem, in which Solomon and the Queen of Sheba are brought together in his spectacular palace. I will first offer a transliteration of the Hebrew in order to be able to refer to the sounds of the original. Then I will quote Stephen Mitchell’s heroically resourceful translation that nevertheless encounters a barrier of untranslatability.

Vered ‘ervatah ha-iveret

mukhpelet beritspat hare‘i. Meyuteret

kol ha-zehirut, bah nakat,

‘et yashav ve-od shafat

acharonei ravim

The dewy rose of her dark pudenda

was doubled in the mirrored floor. His agenda

seemed superfluous now, and all the provisions

he had made for her, the decrees and the decisions

he had worked out while judging the last

of the litigants…

Mitchell’s lines are noticeably longer than Amichai’s, but that is probably unavoidable because the structure of literary Hebrew makes possible a concision ordinarily unavailable in English. The provocative rhyme of “pudenda” and “agenda” is certainly in the spirit of the Hebrew original, and the alliteration of d’s and r’s in the first two lines here is a decent gesture toward approximating the abundant sound-play of the Hebrew. Nevertheless, the acrobatic virtuosity with which Amichai somersaults from word to word through likeness of sound is scarcely perceptible in the English.

Let us look at the first line of the Hebrew, consisting of just three words and surely one of the most untranslatable lines in all of Amichai’s poetry. The literal sense is “the rose of her blind sex.” (The term for the woman’s sexual part, ‘ervah, has been translated elsewhere by some of Amichai’s translators with a much blunter Anglo-Saxon term, but it is not an obscenity. It is the decorous biblical word for the “nakedness” one is forbidden to uncover, so it is an indication of sexual anatomy fraught with a sense of secretness or taboo.) But what has happened here is that the sound of one word has led to another, and then another, each one a little surprise: vered (rose) produces ‘ervatah (her sex), which then engenders ‘iveret (blind). The alliteration of r-sounds and the replication of the phonetic pattern e-consonant-e-consonant (“e” as in “egg,” with the first “e” accented) continues in the next line, but that is a secondary effect. The Queen of Sheba’s lovely sex, mirrored in King Solomon’s marvelously reflective floor because she has nothing on under her robe, is a vered because of the traditional poetic association of the rose with the beloved woman’s body, and also because of the petal-like delicacy of the female anatomy. So, vered becomes ‘ervatah, which then is ‘iveret, the last two syllables of this word sounding like a virtual homonym of vered. And there is a discovery in this association of sound: The Queen’s sexual part is blind because it is an orifice, unlike the eye, without the capacity of perception, but also because desire is blind, impelling one where it, not the reasoning mind, wants to go. Toying with the possibilities of an English equivalent for this amazing line, I came up with nothing better than “The sunflower of her sightless sex,” which has a certain alliterative momentum but entirely lacks the sense in the Hebrew of word generating word through phonetic resemblance.

One should add that in these lines Amichai expands a medieval midrash on the biblical account of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10). There is a vigorous interplay here between pondered texts and the imagined lived context that goes beyond allusion.

One should add that in these lines Amichai expands a medieval midrash on the biblical account of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10). There is a vigorous interplay here between pondered texts and the imagined lived context that goes beyond allusion.

Before we move on to more somber uses of playfulness in Amichai’s poetry, I would like to consider one more extended passage from “The Visit of the Queen of Sheba” in order to observe a fuller range of its linguistic inventiveness. Here is the fourth poem in the sequence, entitled “The Journey on the Red Sea”:

Fish blew through the sea and through

the long anticipation. Captains

plotted their course by the map

of her longings. Her nipples preceded her like scouts,

her hairs whispered to one another

like conspirators. In the dark corners between sea and ship

the counting started, quietly.

A solitary bird sang

in the permanent trill of her blood. Rules fell

from biology textbooks, clouds were torn like contracts,

at noon she dreamt about

making love naked in the snow, egg yolks dripping

down her leg, the thrill of yellow beeswax. All the air

rushed to be breathed inside her. The sailors cried out

in the foreign language of fish.

But underneath the world, underneath the sea,

there were cantillations as if on the Sabbath:

everything sang each other.

Mitchell’s translation here is on the whole a faithful and resourceful rendering of the Hebrew, at least until the erotic high-point of the poem where the sound-play in the original becomes spectacular. One small lapse before then occurs in the fourth line (the third in the Hebrew), which should read “her longing and the rings of her belly.” The deletion of the second phrase was perhaps done in the interest of efficient statement, but the omission is unfortunate. The joining of emotion and concrete object is a characteristic Amichai move, extending the high-spirited verbal circus of the poem. The captains navigate both by the map of the queen’s longing and the rings of her belly, just as the fish, perhaps performing as instrumentalists, blow through the sea itself and through the queen’s long anticipations. Less significantly, the “sea and ship” at the end of the sixth line in the English are actually “sea and hull”—the Hebrew dofen suggests, in fact, the inside of the hull, which makes a better match with “dark corners.” In any case, much of the wild inventiveness of figurative language is evident: the Queen of Sheba’s “nipples preceded her like scouts” both because she is headed into unknown territory and because she is aroused.

In a yoking of concrete and abstract combined with a strategy of breaking open idioms that the young Amichai may have picked up from Dylan Thomas, “Rules fell / from biology textbooks, clouds were torn like contracts,” a whole world is pulled apart by the rapture of desire. Instructively, the sexiest moment in the poem is also the point at which the play of language is most intense: “she dreamt about / making love in the naked snow, egg yolks dripping / down her leg, the thrill of yellow beeswax” sounds like this in the Hebrew: chalmah ‘al / mishgal be-sheleg lavan va-chalomot chelmon / ve-oneg donag tzahov. A literal, and unfortunately nonsensical, rendering of these ten Hebrew words would be: “she dreamt of making love in white snow and dreams of egg-yolk and the pleasure of yellow beeswax.” What makes this sequence work wonderfully in the original is the way, yet again, one word tumbles headlong into the next through similarities of sound. Every one of the first seven words has an l-sound. The word for “she dreamt,” chalmah, is picked up in its cognate noun chalomot (dreams), which then magically engenders chelmon (egg-yolk), a word that shares all three consonants of the triliteral root but no etymological or logical connection. This combination is followed by the rich alliteration and assonance of oneg donag, which sounds like a near-rhyme in the Hebrew. One gets a sense that the words are copulating through sound, that in the fantastic imagery an orgy of language has been initiated, in keeping with the storm of desire of the African queen.

Finally, at the end of the poem, the Hebrew poses a different challenge to the translator that is equally characteristic of Amichai’s poetry—an image taken from the apparatus of Jewish tradition, boldly displaced from its original context and scarcely intelligible in English without a cumbersome footnote. The mysterious “cantillations” underneath the world and the sea are ta‘amei neginah, the indications of musical tropes that guide a person chanting a haftarah, the passage from the Prophets recited in synagogue on the Sabbath after the reading of the Torah. The ta‘amei neginah are little musical notations, squiggles and dots above and below the letters in the Hebrew text. As the Queen of Sheba sails through the Red Sea on her way to meet the fabled Solomon, the world and the aqueous realm around her are, like the Hebrew biblical texts, underscored with markings of song: “everything sang each other.”

The exuberance of invention that is exercised so spectacularly in “The Visit of the Queen of Sheba” remains a driving force of Amichai’s poetic imagination even when the mood of his poetry is somber. Consider a poem from the volume Even the Fist Was Once an Open Hand with Fingers, written more than three decades later in 1989. Here is “Summer Evening by a Window with Psalms,” in my translation:

Close scrutiny of the past.

How my soul yearns within me like those souls

in the 19th century before the great wars,

like curtains that want to pull free

of the open window and fly.

We console ourselves with short breaths,

as after running, we always recover.

We want to reach death hale and hearty,

like a murderer sentenced to death,

wounded when he was caught,

whose judges want him to heal before

he’s brought to the gallows.

I think, how many still waters

can yield a single night of stillness

and how many green pastures, wide as deserts,

can yield the quiet of a single hour

and how many valleys of the shadow of death do we need

to be a compassionate shade in the pitiless sun.

I look out the window: a hundred and fifty

psalms pass through the twilight,

a hundred and fifty psalms, great and small.

What a grand and glorious and transient fleet!

I say: the window is God

and the door is his prophet.

The first line is ordinary modern Hebrew with perhaps even a hint of the bureaucratic. The expression at the beginning of the second line is a Biblicism, mah tehemeh nafshi, “How my soul yearns,” and carries the literate Hebrew reader directly back to Psalm 42:5, which in King James reads, “Why art thou cast down, O my soul? and why art thou disquieted [tehemi, the verb I have rendered as “yearns”] in me?” I would guess that Amichai’s 19th-century souls might be ones he knew from the great novels of the period—Madame Bovary, Middlemarch, Anna Karenina—souls that could at least dream of grand shimmering horizons of fulfillment. The quiet segue from souls to curtains tugged by the wind at the open window and wanting to fly is another one of those characteristic splicings of the spirit and the material quotidian that we observed before.

The poem then moves into a meditation on mortality in the second stanza. The short breaths are a figure for all the countless ways in which life takes the wind out of us, though they may also be an ironic glance at our culture’s preoccupation with physical fitness. The simile of the murderer is a vivid instance of how Amichai uses surprising figurative equations to shock us into recognition. Perhaps we are not all guilty of some terrible crime, but existence treats us as though we were, sentencing each one of us to death, and at best indulging the desire for the condemned person to come to the gallows hale and hearty.

The poem then moves into a meditation on mortality in the second stanza. The short breaths are a figure for all the countless ways in which life takes the wind out of us, though they may also be an ironic glance at our culture’s preoccupation with physical fitness. The simile of the murderer is a vivid instance of how Amichai uses surprising figurative equations to shock us into recognition. Perhaps we are not all guilty of some terrible crime, but existence treats us as though we were, sentencing each one of us to death, and at best indulging the desire for the condemned person to come to the gallows hale and hearty.

The Book of Psalms, announced in the title and alluded to in the second line, comes front and center in the third stanza. Of course, one can describe the still waters and the green pastures and the Valley of the Shadow as allusions to the twenty-third psalm, but I think something is happening here, and in the rest of the poem, that goes beyond allusion. The speaker is contemplating the biblical text—he is, as he sits at the window on a summer evening, “with” Psalms—in the light of his own existential knowledge of the world. The ancient Hebrew words stand before him, and their message of comfort and reassurance does not match what he sees in the world. The soaring hopes of the 19th-century souls proved to be delusions, and after the great wars, delusion itself is scarcely feasible. “Shade” and “shadow” are the same word in the Hebrew, and “shade” in Psalms is a recurring term for protection, but no such protection is forthcoming in a world where deserts stretch wide around, unavailing small patches of green pastures.

The poem’s penultimate stanza takes this move a step beyond allusion. The psalms on which the speaker has been brooding become, through metaphor, physical objects that meet his eye, like the window and the curtains. A miniature armada of the hundred and fifty canonical psalms passes before him in the fading light. These psalms make a grand array, for they are moving poems he knows and loves, but they are also something passing by, transient (cholef). The poet can admire their splendid display but he cannot reconcile their promises and consolations with his own sense of the human condition.

This perception of an unbridgeable gap between the speaker and the remembered text leads to the starkly simple language of the assertion of the poem’s last two lines: “I say: the window is God / and the door is his prophet,” which are obviously framed on the model of “Allah is God and Mohammed is his prophet.” Such an appropriation of theological language to express a secular sense of reality occurs often in Amichai’s poetry. The poem began with a man sitting at a window, looking out into the twilight. It concludes, having woven in and out of Psalms, with the declaration that, after all, we have only the here-and-now: there are no beckoning horizons of aspiration, as in the 19th century, and the Lord is not our shepherd; there is only the full revelatory presence of what we can see and touch.

In Amichai’s last book of poems, Open Closed Open, published in 1998, this idea of biblical texts as objects that are part of the reality of the speaker is more pronounced than ever before, and a good many of the poems are exegetical or midrashic. The mood of melancholy is still deeper in this volume, which abounds in meditations on transience, loss, and death, including the mass deaths of European Jews at the hands of the Nazis. Yet the manifestations of poetic playfulness—punning and sound-play and wildly inventive metaphor—are almost as abundant here as in “The Visit of the Queen of Sheba,” as can be seen in “Gods Change, Prayers Are Here to Stay,” which I shall quote in the admirable translation by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld.

A collection of ritual objects in the museum:

spice boxes

with little flags on top like festive troops

and many fragrant generations of sacrifice,

and the memory of many Sabbath nights that did not end in death.

And happy menorahs and weepy menorahs and oil lamps

with the pouting beaks of chicks like children singing,

their mouths open in desire and love.

And long metal hands to point out everything

that is no more. The human hands that held them—

long since underground, severed from the bodies.

Seder plates that rotate at the speed of time

so it seems they are standing still, and kiddush

cups

in a row on the shelf like soccer trophies

or victory cups from the track and field of generations.

All is gold of grief, silver of longing,

copper of calamity. A collection of ritual objects

like the gaudy toys of a baby god, the gift

of an aged nation, like the strange instruments

of a ghost orchestra, like some odd motionless

bottom fish deep in the waters of time.

A collection of ritual objects donated by Dr. Feuchtwanger,

Jerusalem dentist. And whoever hears this will

assume

a delicate smile on his lips, like well-wrought filigree.

This contemplation of ritual objects—presumably under glass—becomes a moving elegy for the vanished Jews of Europe. The poem quickly moves from the spice boxes, used in the havdala ritual that marks the end of the Sabbath through “fragrant generations of sacrifice”—dorot nikhoach is literally “generations of fragrance” but nikhoach is a term for fragrance associated with sacrifice in the Bible—to the generations of Jews who held those spice boxes and chanted the words of the ritual. A series of poignant puns is initiated in the fourth line. “Sabbath nights,” that is, Saturday nights, in Hebrew is motzaei shabbat, literally the exit or going-out of the Sabbath. This innocent idiom indicating the end of the holy day is transformed by word-play into a grim image of extinction, from the exit of the Sabbath to the exit into death. Three lines down, “in desire and love,” is an intensifying rich rhyme, be-ta’avah ve-ahavah, which is immediately followed by the “long metal hands,” which are actually finger-shaped pointers, usually made of silver, used for reading the Torah. The metal hands pointing to what is gone then lead, in a macabre pun, to human hands severed from their bodies.

“Seder plates that rotate at the speed of time,” is a nice translation of a line that provides a concentrated thematic focus for the entire poem. The conventional phrase is, of course, “the speed of light,” that ultimate limit of velocity, but here, it is time itself that is imagined traveling at 186,000 miles per second, in its horrific rush sweeping away all that was once cherished. If something could travel at the speed of time, it would seem to be standing still, and that is the odd and gloomy reflection that occurs to the speaker as he looks upon the seder plates and kiddush cups from an era that with all its human population is forever gone.

At this point, Amichai’s partiality for sports imagery comes to the fore, reinforcing a sense of deeply gloomy playfulness. The cups for the kiddush ritual celebrated at innumerable Sabbath and festival dinners become “trophies . . . victory cups”—also often kept under glass—”from the track and field of the generations.” The generations of fragrance at the beginning of the poem are now human generations that once strove, attained their triumphs, and in the end, were wiped out. Amichai’s fondness for metaphors drawn from athletics reflects not only his own interests—he was an avid soccer fan—but also a sense that this realm of play regulated by complicated rules is an apt analogue for poetry.

Amichai’s predilection for the yoking of heterogeneous elements through metaphor plays a key role here in the superimposition of sports imagery on ritual objects, the joining of the sacred with the profane. A related move, in which playfulness leads to melancholy, is the pointed reversal of the traditional idea of God as father and Israel as his children, in which the ritual objects are imagined as toys of a baby god given him by his aged people.

The summarizing image of the ritual objects involves an intricate play of sound similar to what we observed in the sexual imagery of “The Visit of the Queen of Sheba”: “All is gold of grief, silver of longing, / copper of calamity.” The use of alliteration in the Bloch-Kronfeld translation is remarkably resourceful, but the clustering of related sounds in the Hebrew is still more intricate and intense: ve-hakol zehav ‘akhzavah ve-khesef kisufim / u-nechoshet ha-choshekh. The first of the three phrases, zehav ‘akhzavah (literally, “gold of disappointment”) repeats so many phonemes that it creates a sense, like the examples we looked at from Amichai’s early erotic poem, that the second word is somehow generated by the one that precedes it. The same dynamic is even more pronounced in the next two phrases. Kesef kisufim (silver of longing), suggests an intrinsic link between the two terms, which display the same three-letter root, k–s–f, and may conceivably have an etymological connection (the face turned silver-pale through longing). The final phrase, nechoshet hachoshekh (literally, “copper of darkness”) combines a replication of consonants with strong assonance, so that the last two syllables of each word, choshekh / choshet, each with a penultimate accent, almost perfectly echo each other, only the consonant at the end changing. The result of all this interfusion of sound is that the precious metals out of which the ritual objects were fashioned are transmuted into mythological tokens of an eternally irremediable sadness: the gold, silver, and copper used to glorify God’s commandments are now witnesses of an unending bleakness to which they are wedded by their very sounds.

In the last three lines of the poem, the speaker emerges from his darkly meditative immersion in a vanished world to the surface of the Jerusalem museum and the quotidian reality of a dentist named Feuchtwanger who collected ritual objects. The injunction to smile at the end of the poem is an enforced substitute for tears: we have no choice but to go on, after all that has been irrevocably destroyed, but the smile on the lips is mere artifact, ironically mimicking the artifacts on display that are the sole sad remnants of the Jews who once used them in joy and devotion.

Play is something we generally associate with pleasure, and there are abundant illustrations of that nexus in Amichai’s poetry, especially, though by no means exclusively, in his erotic poems. But language is, after all, an instrument of meaning, and so the play with language also becomes a vehicle for the discovery of unanticipated meanings, some delightful, others somber. Amichai was a zestfully inventive poet who reveled in the linking of words through intricate combinations of sounds and in the joining of the most disparate concepts through the force of metaphor. He exercised this faculty with equal vigor whether he was imagining the allure of the sensual world or peering into the abyss.

Play on the soccer fields or the running track is a competition bound by rules in which someone ends up taking home the championship cup. Play in the fields of verse when it is done as skillfully as in Amichai’s poetry has no losers: the reader, through the gift of the poet’s virtuosity, is offered the prize of repeated new recognitions.

Suggested Reading

What Goes Into Survival: A Report from the Washington Rally

People came by the hundreds of thousands, schlepping by train, chartered bus, overnight flight. Students raised money from relatives. Federations funded last-minute airfare. It was a rally for people who don’t attend rallies.

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Free Radicals

The history of American anarchists, and of Jewish anarchists in particular, has been forgotten, largely overshadowed by the history of the American communist movement.

“When Orchards Burn Their Lamps of Fiery Gold”

Emma Lazarus’s 1882 poem for Rosh Hashanah responded to the crises of her day, foreshadowed “The New Colossus,” and resonates today.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In