The Day School Tuition Crisis: A Short History

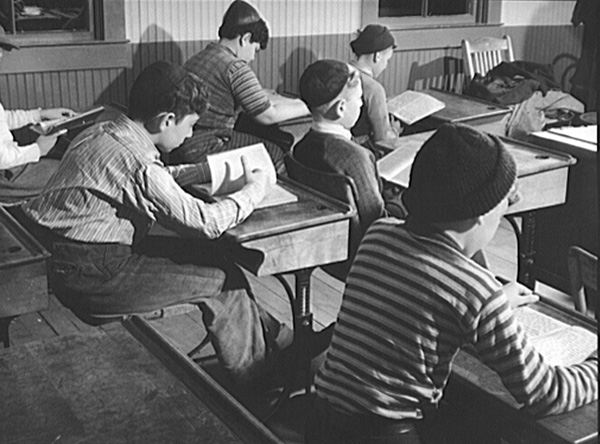

When New York’s police commissioner complained in 1908 about young Jewish immigrants’ disproportionately high rate of street crime and truancy, he wasn’t demanding that they spend more time in Hebrew school. But his comments unwittingly spurred the most massive effort to improve Jewish education that American Jews had ever seen. A cadre of Jewish philanthropists and educators, stung by the commissioner’s accusations and contending with hundreds of thousands of immigrant children whose parents had little time or money to invest in Jewish schooling, set out to professionalize Jewish education in New York and situate it as a communal—rather than family or congregational—responsibility.

A century later, in the midst of the biggest financial meltdown most American Jews had ever seen, the question of communal responsibility for Jewish education was at the forefront again. The problem to address was no longer kids pickpocketing and skipping school, but rather unsustainable school budgets and Jewish families hit hard by the financial crisis. Many feared that, as during the Great Depression, Jewish education would fall low on the Jewish community’s overburdened agenda. Of particular concern was the day school system, one of the biggest success stories of post-World War II Jewish education, but also the most expensive. Funding this system, which by 2008 stretched over more than eight hundred schools and more than two hundred and twenty-five thousand youth, had always been a problem. Now the unresolved questions of how much parents could bear in tuition payments, schools could bear in enrollment and revenue shortfalls, and communal organizations could bear in subsidizing this system assumed new urgency.

At the time of the police commissioner’s infamous report, the majority of the three hundred and sixty thousand elementary-aged Jewish children in the United States were receiving no formal Jewish education at all, and the schools that did exist were mostly inadequate. Institutions such as the Bureau of Jewish Education of New York and the Teachers Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary sought to rectify the situation by creating standards for the vast network of schools and those who taught in them. In 1937, following the twenty-fifth anniversaries of these institutions, Israel Chipkin, head of the Jewish Education Association of New York City, published an assessment of the progress of American Jewish education.

Much had changed. The number of American Jewish children of elementary school age had increased to eight hundred thousand, due in large part to mass migration from Europe (which had, however, virtually ceased after the immigration legislation of 1921 and 1924). Only about a quarter of these children were receiving any Jewish education. Nonetheless Chipkin could write an extensive report on a broad array of positive developments, including a few pages devoted to the “all-day school,” which occupied a relatively small but growing part of the Jewish educational network. In 1901, there were only two day schools in North America; by 1935, that number had grown to eighteen, from the “Old-type Yeshibah,” to the “Modern-type Yeshibah,” to the “Private Progressive-type.”

Despite his general optimism about the future of Jewish education, Chipkin was skeptical about the “all-day” format:

All these all-day schools are essentially institutions for the few and the select. They are financially prohibitive to the masses and cannot readily become the typical community school.

Although he believed that there would continue to be “a sufficiently interested minority within the community who will make every sacrifice to maintain them” and expected these schools to “supply that contingent of intensively trained Jewish youth who enter our higher schools of Jewish learning,” he concluded that they “must always remain the opportunity of the exclusive few.”

As a disciple of the great Jewish educator Samson Benderly, it is not surprising that Chipkin concentrated most of his attention on the Talmud Torahs, intensive afternoon supplementary schools, which would provide a substantive Jewish education without precluding the Americanizing experience of the public schools. Yet, Chipkin’s assessment of the day schools’ prospects cannot be dismissed as merely the biased reflections of a supplementary school advocate. As historian Jonathan Krasner notes, even Chipkin sent his children to day school.

If Chipkin had revisited the scene a quarter of a century later, he would have had some real changes to report. By the mid-1960s, the growth of the Orthodox community, revived interest in things Jewish sparked by the Holocaust and Israel, disenchantment with public schools, and a postwar ethnic revival led to very significant growth in the day school movement. In 1940, there were thirty-five day schools enrolling 7,700 students in seven states and Canadian provinces; by 1964, these figures had grown to 306 schools in thirty-four states and provinces, enrolling 65,400 students. Roughly nine percent of those children receiving some form of Jewish education in the United States attended a day school; in New York City, that figure was closer to twenty-nine percent. Most of these schools were under Orthodox auspices, launched by the Torah Umesorah movement and other organizations that sought to promote Torah education in America.

While it was common for non-Orthodox families to send their children to Orthodox institutions, day school advocates within other movements began laying the groundwork for their own schools. These proponents argued that only a truly intensive Jewish education could prepare future leaders of their movements, especially in a post-Holocaust world that no longer had the reservoir of European Jewry to provide an intellectual and cultural elite. The Reform community did not establish its first day school until 1970 and supporters were in the minority until then, but Emanuel Gamoran, one of the pioneers of Reform education, made a sympathetic case for such schools in 1950: “We must admit that there is a great need for the training of Jewish leadership of which Hebraic education is a basis. We have no such basis now in the ranks of Reform Judaism. Without it we shall be largely dependent on Orthodox and Conservative Jews to supply us with children who have a sufficient Hebraic background to go into Jewish work, into Jewish education, or into the rabbinate.” Day school advocates among Conservative Jews, who began setting up day schools in the 1950s, made a similar argument. “The growth of the day school will help the Conservative movement to create a reservoir of intensely educated and deeply dedicated men and women,” declared the United Synagogue Commission on Jewish Education in 1958.

Nonetheless, outside of ultra-Orthodox circles, most mid-century Jewish parents simply did not regard day schools as necessary or an option. Day schools were not on the radar of the vast majority of American Jews, who were more accustomed to sending their children to an afternoon school or Sunday school at their local congregation. Moreover, statements like those of Gamoran and the United Synagogue Commission on Jewish Education notwithstanding, many, perhaps most, postwar Reform and Conservative Jews had profound misgivings about a day school system that threatened to undermine both congregational schools and the hard-sought integration of Jews into the wider American society.

One of the factors that impeded enrollment in day schools, even within the Orthodox community, was the very same problem of tuition that Chipkin had described. While the postwar economic boom emboldened American Jews to set up hundreds of day schools, the great cost of sustaining these schools always hovered over their efforts. Writing in 1955, the principal of a Brooklyn yeshiva complained about the difficulties involved in providing financial aid:

I know of no central educational agency that has attempted to bring to the lime-light the question of tuition. And yet, the very problem has been annoying and embarrassing to parents, [and] vexing to the school . . . What policy, if any, may a Yeshiva pursue in the admission of children? Shall all applicants be admitted regardless of the parents’ ability to pay? Or shall certain “quotas” . . . be established to regulate admission? If the first be adopted, such a liberal policy might soon deplete the school’s funds and deprive all children, paying or non-paying, of a Yeshiva education. On the other hand, the second course might exclude too many children clamoring for admission.

An attorney active in the day school world bemoaned that growing enthusiasm for day schools did not resolve the question of how to support them: “In the past few decades, the Yeshiva movement has made tremendous progress in the United States and Yeshivos have not only become accepted but have become increasingly popular…The most important problem that is facing the normal progress of the Yeshiva movement today—as always in the past—is the lack of funds.” A half-century later that complaint still resonates.

While the burden of tuition and balancing the budget always caused much worry among day school families and administrators, it was not until the 1980s and 90s, when many people began to see an all-day program as the sine qua non of “serious Jewish child-rearing,” that these financial problems became an issue on which much of the Jewish future seemed to ride. A “continuity crisis” had engulfed the Jewish community, with reports of waning Jewish affiliation, especially among the young. The National Jewish Population Survey, issued in 1990, shocked the Jewish community with its claim that roughly fifty percent of American Jews intermarried. “The Jewish community of North America is facing a crisis of major proportions,” declared A Time to Act, the landmark call-to-arms report issued that same year. “Large numbers of Jews have lost interest in Jewish values, ideals, and behavior, and there are many who no longer believe that Judaism has a role to play in their search for personal fulfillment and communality.”

The organized Jewish community mobilized on several fronts, but no arena received more attention than Jewish education. Jewish learning—formal and informal, in schools, in camps, for youth, for adults—moved to the forefront of the communal agenda. As A Time to Act put it, “the responsibility for developing Jewish identity and instilling a commitment to Judaism for this [disaffected] population now rests primarily with education.” More so than any point in the history of the modern day school movement, educational, communal, and philanthropic leaders viewed day schools as the best hope for saving American Jewry. Day schools are “arguably the most impactful single weapon in our arsenal for educating Jewish children and youth,” asserted the 1995 Report of the North American Commission on Jewish Identity and Continuity. Day schools were no longer solely the province of Orthodox families or those who sought an alternative to the public school system; they were for any family who cared deeply about raising Jewish children. This message resonated particularly with parents who had attended the supplementary schools in the 1960s and 1970s and who lacked the Judaic skills they sought so eagerly for their daughters and sons.

But these schools were also “seriously underfunded,” according to the first comprehensive study of day school finances commissioned by the AVI CHAI Foundation in the school year 1995-1996. And if proper investments were not made in improving school facilities, faculty salaries, Judaic and secular programming options, and the like, “most American Jews may never consider this form of education, and even when they do, will not elect it.” A flurry of activity on the part of philanthropists, foundations, federations, and organizations to improve and build day schools, in addition to high fertility rates among Orthodox Jews, resulted in significant growth in enrollment, as noted by a series of studies conducted by Marvin Schick for AVI CHAI over the following decades. In 1998-1999, there were one hundred eighty-five thousand students attending 670 day schools, which represented an increase of twenty thousand to twenty-five thousand students since the early 1990s and twenty percent growth in non-Orthodox schools; by 2008-2009, there were more than eight hundred Jewish day schools in the United States, matriculating 228,174 students, which represented an enrollment increase of twenty-five percent over 1998-1999, including five percent growth in non-Orthodox schools (the greatest increase being in community day schools, which accounted for roughly nine percent of day school students, followed by almost six percent in Solomon Schechter schools, and two percent in Reform schools).

Despite these successes, a sense of foreboding about day school finances persisted into the early 2000s, spurred by underlying weaknesses across numerous institutions: low enrollments, a paucity of endowments, budget deficits, and this all in the context of what the historian Jack Wertheimer has described as “the high cost of Jewish living.” While the devastating economic events of 2008 exacerbated these problems and catapulted them into a crisis, it was a crisis that had been brewing for years and one that several observers saw on the horizon.

The most recent statistics suggest Orthodox and community day school enrollments had small to non-existent growth 2012-2013 relative to the previous year. But, declines continue to be seen in Reform and Conservative institutions, and there is concern about the financial impact on families who remain in the system and the viability of smaller schools. The oft-repeated joke, already circulating in the 1990s, that day school tuition was one of the most effective forms of contraception in Jewish families, is met today with more of a wince than a chuckle in some Jewish circles. Rabbis Aryeh Klapper and Yitzchok Adlerstein have recently made the argument quite seriously for different parts of the Orthodox community.

The NYU economist Paul Romer, among others, has observed “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste,” and the organized Jewish community has taken note. With the very real threat looming overhead that day schools could become “financially prohibitive to the masses,” foundations, federations, research institutes, and day schools have mobilized in unprecedented fashion. They are focusing not simply on promoting day schools and offering short-term solutions to tuition shortfalls, but on creating structural changes that will sustain these institutions in the long run. Many of their ideas will bear fruit—if at all—several years from now; the question remains how lower-and middle-income families and schools on the edge will fare in the interim.

Suggested Reading

A Decade of Recommendations

In celebration of our 10th anniversary, we asked 10 of our favorite readers which books they had found themselves recommending the most over the last decade.

Faith in Doubt

Can doubt provide the space that allows secular and religious Jews to coexist in Israel?

Pew’s Jews: Religion Is (Still) the Key

Who are the “Jews of no religion” in the much-discussed Pew Research Center's “A Portrait of Jewish Americans”? It’s a question that gets at the deep structures of Jewish life and the inadequacy of many of the sociological methods used to describe it.

Could It Have Happened Here? The Implausible Plotting of The Plot Against America

Was America in 1940 primed for an antisemitic leader, as Roth and his adapters would have us believe?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In