Scenes of Jewish Life in Imperial Russia

What was Jewish life like in Russia in the years before the revolution? It certainly did not take place in an unchanging shtetl, as historians of the period have repeatedly reminded anyone who was listening. But even those who know a great deal about the enormous economic, social, religious, and political changes Russian Jewry was then undergoing may not have much of a feel for what this meant in the everyday lives of Russian Jews. With the publication of a new anthology, ChaeRan Y. Freeze and Jay M. Harris have opened many long-shuttered windows onto the vanished courtyards of a world in transition. What they display to us are not trends and movements but individuals facing and coping with a variety of new problems as the ground shifts beneath them.

In the first of three excerpts from Everyday Jewish Life in Imperial Russia (Brandeis University Press), an abundantly annotated 600-page sourcebook, we hear Ita Kalish’s reminiscences about the way in which her Uncle Bunem spied on a prospective groom at the behest of her father, the Hasidic Rebbe of Vurke. What kind of medicine was the young man really taking while staying at a luxurious kosher pension?

In the second excerpt, Avraam Uri Kovner (himself somewhat infamous for having been convicted of embezzlement and corresponding with Dostoevsky from jail) describes his brother’s success in one of the first government-run Russian Jewish schools with a modern curriculum. When he delivered a fine speech in Russian, the district supervisor at first couldn’t believe that a Jewish boy could do such a thing and then smothered him in kisses.

The last excerpt documents a husband’s bitter struggle to prevent his wife from becoming a dentist. In her quest for “development and self-reliance,” the woman seeks her government’s help—and obtains it. Here, as elsewhere, the reader is struck by the pervasive presence of the state in the lives of Jews in the decades that preceded the Russian Revolution.

The Vurke Hasidic Court in Otwock: The Memoirs of Ita Kalish

I recall my mother mostly as a sick, weak woman, lying for hours on the couch in our long, dark dining room—and in later years—in the long hammock at the villa of my grandfather, Rabbi Simhah Bunem of Vurke [Warka, in Polish] in Otwock, of blessed memory. She was sick for many years; she always had a special nurse and frequently traveled to spas abroad. She was often sarcastic and critical of people, ready with a caustic phrase for anyone whom she did not like, but redeemed by a genuine sense of humor and innate wit. She was especially disparaging in her accounts of Galician Jews, whom she encountered at Austrian spas. “The Jews over there,” she would say, “consider themselves to be real ‘Austrians’; they speak ‘datsch,’ their men shorten their coats, and their women wear wigs instead of traditional Jewish bonnets.” My mother’s nurse Freydl, who happened to come from Galicia, once created a major stir in our house. This happened on Yom Kippur eve, right after “Kol Nidrei,” when my father, together with his eldest son, brothers, relatives, disciples, and old Vurke Hasidim—all wrapped in their tallis adorned with silver crowns—returned home from the great synagogue. They came to rest after Kol Nidrei and to prepare for the long Yom Kippur night and discovered Freydl washing herself with soap in the kitchen. I remember my mother’s scathing remark at this desecration of the holiday: “What do you expect from a Galits-ianer?” The day after Yom Kippur, Freydl packed up her belongings and left our house.

The one who remained to take care of my mother was her older and beloved sister, “Feygele the Pious” as she was known in her hometown of Kozienice. Every year Aunt Feygele used to fill the cellar of our house with bottles of raspberry juice for the sick and poor people. Raspberry juice was considered a sure way to induce sweating, which was thought to be an effective remedy against all kinds of colds. In the wintertime, any poor resident of Kozienice could receive a bottle of raspberry juice from Feygele. Aunt Feygele was very modest and humble. With a gentle smile on her pale lips, she was always ready to forgive the world any wrongdoings, even those committed against her own person. For thirty years—ever since the day of her wedding—Aunt Feygele lived together with her husband’s parents, and her old mother-in-law, not Feygele herself, was in charge of the house. Yet during all those years, no one heard the two women raise their voices at each other. Aunt Feygele would often leave her husband and children in Kozienice and spend weeks sitting at the bedside of my sick mother, smiling good-naturedly and telling her all kinds of stories.

The town of Maciejowice, where we lived for a few years, consisted of a circular marketplace, a few narrow streets, and a big road leading to the surrounding gentile villages. It had a synagogue, a mikvah, two trustees, a Jewish mailman, a Jewish population with enough men for a few minyanim, and a river, the Dzika. The town’s women told each other with fear that the Dzika demanded an annual sacrifice; each year someone would drown there. My mother, a daughter of a wealthy family from a big city, always felt antipathy toward the shtetl, which only increased after her own daughter nearly became another victim of the Dzika. This happened on a hot summer evening, when my mother took me along to the river. Children of every age were having a wonderful time, bathing and splashing in the water. Every moment, my mother would remind me that I should hold on to her. I have no idea what happened later: all I remember is opening my eyes and finding myself lying on the grassy riverbank surrounded by all the women and children of the shtetl, with my terrified mother and a Polish doctor next to me. We never went swimming in the Dzika again.

Mother came from a wealthy hasidic family in the Polish-German border town of Będzin [Bendin, in Yiddish]—the “Bendiner Orbachs,” as one used to call the family in that border region. I first saw my grandparents from Będzin when they were already elderly and nothing remained of their former wealth. Grandmother’s pride and sagacious silence, and Grandfather’s humor and wit—his grandchildren enjoyed immensely. I remember him once on a summer Sabbath morning, strolling around the yard in front of our great synagogue during the intermission between the Shacharis and Mussaf prayers. He beckoned to me and, smiling broadly behind his large gold-rimmed spectacles, reached into the pocket of his long coat. “So what would you like?” he asked me innocently. “Ten grozsy or a złoty?” I remained standing, frightened and cried out: “But it’s Shabbes!” I immediately realized that Grandfather was only joking and both of us, the eighty-year-old man and his little granddaughter, burst out laughing, pleased with each other’s great sense of humor.

My aged, medium-built, and corpulent grandfather, Pinkas Orbach, white as a dove—a whiteness accentuated by his satin caftan and large black velvet hat—was grateful to God all his life for the great privilege of marrying off his daughter to a member of the celebrated Vurke court. He was proud of his youngest daughter, my mother Beylele, the oldest daughter-in-law at the Vurke court, and even more proud of his Vurke grandchildren, as children in our family are called to this day. In addition to Grandfather Pinkhas and Aunt Feygele, another member of my mother’s large family, her only brother, known as Bunem Sosnovtser, would often come to visit us, staying for weeks at a time. Uncle Bunem’s big black eyes were always smiling, sometimes sarcastically and sometimes humorously. He was very handsome: tall and slender, distinguished by his elastic, almost dance-like walk. As the only son in a household with six daughters, he was very spoiled from his earliest childhood, and his whole life; even after he had several children of his own, he paid little attention to the mundane necessities of life. He spent most of his time in various hasidic practices at the house of his brother-in-law, the rebbe, and had the reputation of a genteel young man—very popular and beloved among the Hasidim.

The chief breadwinner in Uncle Bunem’s family was his wife, Miriam. Aunt Miriam required neither a bank nor bank clerks to conduct complex commercial and financial transactions. Her hometown of Sosnowiec had a large number of thriving money exchange offices, and she was able to make the most difficult and confusing exchange calculations in her head, without pen and paper. She was very clever, energetic, and renowned as a laytishe yidene [a resourceful Jewish woman]. Once, at my father’s request, Aunt Miriam went with my youngest sister, who was then suffering from a childhood disease, to a professor in Berlin. When they returned, the entire family surrounded Aunt Miriam, waiting impatiently to hear what the professor had said. Aunt Miriam stood in the middle of the room, smiling playfully, and said, “The professor, you say? He said it’s nothing. It’s something for a rebbe to deal with.” In later years, when my father was already the rebbe, Uncle Bunem performed various important duties at our court, including the “investigation” of the marital matches offered to my father for his younger daughters. My father was very proud of his children, and in response to offers of matches with Poland’s great hasidic courts or business magnates, once remarked: “Whatever match I pick for my daughter, I will always lose.” Uncle Bunem, his devoted “secret messenger,” would bring a lot of news about the candidate to become the rebbe’s son-in-law. Once it actually happened that Uncle Bunem failed miserably in his task. Here is how it happened. An almost certain candidate to become the son-in-law at the Otwock court, a young man of about sixteen to seventeen years of age and closely related to a famous rebbe in Poland, came to recuperate at one of the large, expensive pensions in Otwock following a severe cold. My father, always concerned about the health of his children, immediately ordered Uncle Bunem to go to that pension as a “visitor” in order to find out directly whether the potential groom’s stay there was indeed for nothing more than ordinary recuperation after an ordinary cold. With great effort and with the help of various stratagems, my Uncle Bunem succeeded in moving next door to the young man. After several days of enjoying the great culinary art of the famous pension of that time, he discovered several little bottles of medicine prescribed by a great Warsaw doctor on the potential groom’s night table. Before my father had enough time to make up his mind concerning this serious matter, the boy’s father became aware of the whole “espionage racket” and, feeling terribly insulted, refused to discuss further the match with the “Vurke granddaughter.”

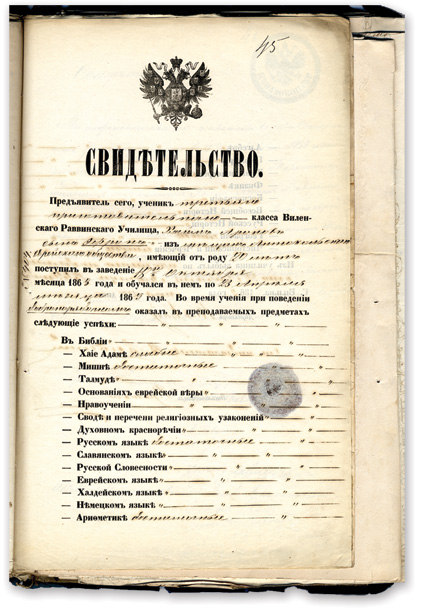

Avraam Uri Kovner: The Vil’na Rabbinical School

How and why our family came to be in Vil’na again, I do not remember—I only know that Grandmother sold her “estate.” However, nurturing a special passion for land, for “one’s own” little corner, she bought some kind of shack in the forest (not far from Vil’na) and moved there. But it had no space for our family. Nor do I remember how I, a nine-year-old boy, suddenly turned out to be a student in the first class of the Vil’na Rabbinical School. Whether they required some kind of examination to enter this school and whether I took this examination are things of which I have no distinct recollection. I only know that one nasty day I found myself among little children, students of the first class in a large, bright room on the second bench.

However, a few words need to be said about this school. When it was established, it was meant to cultivate educated state rabbis and teachers for urban Jewish schools. The curriculum at the rabbinical school was eight years (like our gymnasiums), except for Latin (which apparently was not obligatory then—even at the gymnasiums under the Ministry of Education). However, German and Hebrew, study of the Bible, and some knowledge of the Talmud were obligatory, along with the fundamental principles of the Jewish faith according to Hayei Adam [The life of man] and the Shulhan Arukh [The prepared table], which concisely and systematically laid out the foundations of the law of Moses. The head of the school was the director, a Christian; the assistant inspector and all the teachers of general subjects were also Russian and enjoyed the rights of state service. Only the inspector and the teachers of Jewish subjects were Jewish; the inspector, moreover, was not invested with any power and [had been] appointed only for honorific reasons from [among] the prominent Vil’na Jews. Instruction, except for special Jewish subjects, was in Russian.

The school, which occupied a large stone building, had a dormitory that housed a certain number of the most gifted students at public (that is, Jewish) expense. Among them was my older brother, subsequently well known in the medical world as the author of an extensive historical work. How my brother ended up there, I do not know—all the more so since the rabbinical school was considered a hotbed of freethinking and atheism among Orthodox Jews (which my parents were), and none of them sent their children there. My parents’ motive for sending their own firstborn to this impious institution was undoubtedly the fact that rabbinical school students were exempted from military conscription (something that not only Jews deemed terrible—given the brutal conditions of the Nikolaevan era). Their sons, however, given that they knew neither the Russian language nor the Russian way of life, considered [attending] this school to be the greatest misfortune. A considerable incentive for my parents must have been the desire to be rid of an extra mouth to feed, all the more so since, as a special exception for the first class, my brother was admitted at public expense.

In terms of the Jewish subjects, I was better prepared than the others. But back then, Russian was completely alien to me, and hence I had absolutely no understanding of the lessons in general subjects. Soon, however, I began to make notable progress and would have fully mastered Russian had a severe illness not befallen me. I was a day student. Every day at 4:00 to 5:00 in the morning, I set out for school with my brother, who helped me prepare the homework; during these excursions in the winter, dressed extremely lightly, I caught a severe cold and came down with a fever. I stayed home in bed in dire circumstances for more than three months, all this time remaining nearly unconscious. When I finally recovered, thanks to a strong body, and showed up at school, the teachers did not recognize me and asked: who is this? After the illness, I did not remain for long at the school. My parents apparently took my illness as a punishment from above for attending the impious institution, so they withdrew me and planted me in front of the Talmud. “It is enough,” said Father, “that one son of mine is an atheist; woe unto us if another (that is, I) becomes a goy ([which, according to him, meant] an apostate from the Jewish faith).”

The relationship of my parents to their oldest son was strange. Living in the dormitory at the rabbinical school, he rarely visited the parental home, and my parents never visited him at the rabbinical school. When my brother did appear at home for the big Jewish holidays, he felt like a stranger, remaining constantly reticent and sullen. My parents, considering him lost for the Jewish religion, were indeed ashamed of him. They tolerated him like an unavoidable evil: they never greeted him, caressed him, especially Mother, despite the fact that he was an extremely talented and hardworking student, quiet and modest, and most important—he did not cost them anything.

I will also recount an episode from my brother’s life that characterized my parents’ treatment of him at the time. Brother was in the sixth class when the school celebrated the first decade of its establishment [in 1847]. Apart from the educational authorities and the district superintendent, Adjutant General Nazimov (the former general governor of Vil’na) was present at the celebrations. Three of the best pupils of the school were to deliver a speech in Russian on this occasion. It fell to my brother’s lot to deliver a speech in Russian. General Nazimov, having heard the speech, at first did not believe that a Jewish boy had spoken, but when the supervisor of the district confirmed this, the governor general beckoned for my brother to come to him, smothered him with kisses before the whole audience, hoped that he would perfect his learning, and wished him every success in life. News about this spread to all the Jews of Vil’na, and many came to congratulate our parents with an unprecedented celebration of their son. But as simple, religious Jews (who are not at all flattered by distinction), they naively declared that if their son had achieved such a triumph in the Talmud, they would have considered themselves far happier.

Having spent “a week short of a year” at the rabbinical school, I understandably did not come away with anything essential—neither an elementary concept of life and non-Jewish interests, nor even [the ability] to read Russian properly. The sole, powerful impression that I took away from the school during my short stay was the public birching of a third class student, a lanky fellow of sixteen or seventeen years of age.

The Impact of Women’s Higher Education on Marriage

“Petition of Chaim Davidovich Grinshtein (Son of an Odessa Merchant) to His Imperial Majesty’s Chancellery for the Receipt of Petitions

(Received on 1 December 1899)”

GREAT MONARCH! MOST GRACIOUS SOVEREIGN! I take the liberty to fall at Your Majesty’s feet with this humble petition. I have been married to Revekka L’vovna Grinshtein for eleven years and have had two children with her—a daughter Raia (seven years old) and a boy Mikhail (three years old). Until the past year, our lives passed by happily and quietly, without storms and agitation; however, at the beginning of last year, my wife took it into her head, for no reason at all, to go off to a course in [dental] medicine and, in order to attain this, registered with the medical inspector, Dr. Korsh, in Odessa, who permitted her to practice with a dentist in the town of Korabel’nikov. All of my protests and appeals to Dr. Korsh not to permit my wife to practice without my consent were futile and had no effect. In the end, my wife left me and our minor children to the will of fate and devoted everything to the goal of studying dentistry. [This was] not due to necessity because I, thank God, am a man of means; I have provided and continue to provide for my family with abundance.

As a result of the illegal permission, my wife practices dentistry, and with each passing day I am ruined, as my business fares badly; I have lost my head and the small children suffer worse than orphans, being left without the tenderness and care of their natural mother. The heart of any person with the slightest feeling would shudder involuntarily at the sight of my unfortunate position, living with my little orphans, who are susceptible every minute to dangers such as colds, illnesses, or injury without the care of their natural mother. The tears of the unhappy children calling in vain for their mother are endless; the sight of their tears and bitterness rends my heart. It is sad that in this case, as explained above, my wife’s study of dentistry is not caused by any necessity and appears only to be the fruit of caprice.

Falling at your feet and appealing to the ineffable mercy of Your Imperial Majesty, I beg you, All Merciful Sovereign, to look mercifully on my unhappy children, who are perishing without [their] mother, and save them with your kind word: forbid my wife from engaging in the study of dentistry so that she returns to the bosom of the family, to the joy and happiness of our little children.

“Petition of Revekka Grinshtein to His Imperial Majesty’s Chancellery for the Receipt of Petitions

(17 November 1901)”

Most Gracious Sovereign! Most August Monarch! Among the multitude of people who are shielded by the scepter of the Great Russian Monarch, seeking and appealing for salvation at the foot of the Throne, I turn my eyes to You, who serves as the source of good for all His loyal subjects.

In 1889, at the age of eighteen, I was married to the Odessa townsperson [Chaim] Nukhim Abramov Grinshtein with whom I soon had two children. After the passage of a few years, however, I had time to be convinced that my family life had turned out in the saddest way. Apart from the differences in personalities, I was especially oppressed by the disagreement in our moral worldviews, which became manifest with respect to the meaning of the family, the mother’s role in it, and concern about the upbringing of the children. My striving for development and self-reliance met with desperate opposition from my husband, and I decided to study dentistry to satisfy my thirst for knowledge so far as possible and to support myself and the children with a source of livelihood, being compelled to separate from him. Now I have successfully completed my studies at the local dental school and must take the examination at one of the Russian universities. However, I have been deprived of the possibility of achieving this because my husband, who at first agreed to provide me with his written permission after long entreaties, now abruptly refuses to give me the requisite separate passport, which is necessary for this purpose. This refusal, which obstructs the path to the most cherished dream of my life and has already absorbed a lot of my labor, will leave me completely horrified.

But boundless despair inspires in me the audacity to entrust my fate to the powerful hands of the Father of the Russian lands. In addition, I am submitting four certified copies of certificates of marriage, [my] trustworthiness, completion of dental school, and the agreement of my husband about the continuation of my education. I fall down at the feet of Your Imperial Highness with [this] supplication: make me happy by your gracious command to issue me a passport from the Odessa townspeople board. I am not attempting to dissolve our marriage but strive only for the possibility of living on my own labor and dedicating myself to the proper upbringing of our children.

This petition was written according to the petitioner’s words by the townsman of Bender, Moishe Modko Surlev Finkel’feld.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jewish Acculturation in America: A Symposium

Five leading Jewish thinkers discuss the continuing impact of the American melting pot.

A Cipher and His Songs

Avraham Halfi faced outward, a gifted comic performer, and inward, a lyric poet of resonant privacy.

The Nation of Israel?

The case for an Israeli—not Jewish—republic.

Harvard, SNCC, and an Antisemitic Cartoon

How did Harvard students end up using a decades old antisemitic cartoon in their anti-Israel activism?

Martin Berman-Gorvine

Fascinating! How wonderful that our "foremothers" were no shrinking violets, but forces to be reckoned with in their own right!