Nothing New Under the Sun

The religion of leaders has rarely, if ever, been the religion of the masses. Thus Professor Moshe Greenberg, z”l, on the first day of a course I took on biblical religion, made a distinction between biblical religion and Israelite religion. Biblical religion—the religion of the leaders that is reflected in the biblical books—was a form of ethical monotheism; Israelite religion—that is, what most Israelites were actually believing and doing—was idolatry and licentiousness, as attested in the Torah itself (e.g., the Golden Calf, Ba’al Pe’or) and even more in Former and Latter Prophets and in archaeological discoveries. Later, the “Rabbis” were called Pharisees (perushim), a name that indicates that they separated themselves from the masses because they did not trust the laity’s religious piety or practices. The gap between rabbis and their constituents continued through the Middle Ages, when, for example, the people were using amulets and many other forms of magic and superstition despite strong rabbinic objection to these practices and beliefs, and from then into modern times.

I mention this because as much as it is frustrating for rabbis and others concerned with the content and future of Judaism to see what most Jews are doing, this is an old story. Thus when Daniel Gordis proclaims a “requiem” for Conservative Judaism because 41 percent of American Jews affiliated with Conservative Judaism in 1971 and now only 18 percent do, and when he claims that it is because Conservative leaders focused too much on Jewish law rather than things that matter in people’s lives, he has completely missed the broader historical and sociological scope of the phenomenon.

For very well-known sociological reasons, second-generation American Jews, whose parents came from Eastern Europe, affiliated with Conservative Judaism in droves in the middle of the 20th century. Americans at the time were overwhelmingly “churched,” so Jews who wanted to identify as Americans had to do the Jewish equivalent by belonging to synagogues, and Conservative synagogues represented what they wanted to say about themselves—that they were both identifiably Jewish and modern. The high affiliation rate, though, was a sociological blip, and even then rabbis complained about the gap between what they believed and practiced and what most Jews did.

It is also primarily sociological forces that are at work in what is now the fourth generation of American Jews from Eastern European heritage and in some American Jews from other places as well. They no longer feel the need to prove their American identity, and so they do what Jews have done since time immemorial—they follow the trends of the surrounding culture. The culture of Americans in their twenties and thirties is not to affiliate with anything. They even postpone marriage until their 30s or 40s, if they marry at all. Thus, as the Pew study says, “The increase in Jews of no religion appears to be part of a broader trend in American life, the movement away from affiliation with organized religious groups.”

So how should those concerned with traditional Judaism respond to this sociological pattern? Gordis’ solution of Modern Orthodoxy is in just as much trouble as Conservative Judaism. According to the Pew study, only 3 percent of American Jews identify as Modern Orthodox; 6 percent are Ultra-Orthodox. No wonder why Modern Orthodox rabbis and institutions are forever looking over their shoulder to the right. If you accept Orthodox premises, it is really hard to value modernity. As the founder of Modern Orthodoxy, Samson Raphael Hirsch, asserted, Jews may attend universities, but only if they understand that if they learn something there that conflicts with Judaism, they must believe in Judaism, for that is the word of God and what they learn in universities is the word of humans. And the situation is no better in Israel, where the percentage of Jews who identify as Orthodox has not grown (still about 20 percent), and a similar comparison to 1971 would reveal that within that percentage the Modern Orthodox have lost significant ground to haredim.

So what should Conservative rabbis like Daniel Gordis and me do in light of the facts that the Pew study revealed? Should we talk about what matters in people’s lives, as Gordis suggests? Of course we should—but we have been doing that for decades. Gordis’ own grandfather, Rabbi Robert Gordis, wrote not only about Jewish law, but also about the moral and social issues of his day. For example, his 1962 book, The Root and the Branch, includes chapters on liberty, interfaith discussions, education, race, ethics in politics, and international relations – and my guess is that he spoke about those and many other topics that matter in people’s lives often in the sermons he gave in the large Conservative congregation he led. And he was definitely not alone. Just look at the more recent books by brilliant and sensitive Conservative congregational rabbis like Harold Kushner and David Wolpe on issues as personal as confronting the early death of one’s child or the illness of one’s parents—or the series of books entitled Hearing Men’s Voices, published by the Conservative movement’s Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs, which explore what it means to be a man when the old gender roles no longer apply.

But concern with such topics should not dissuade us from also talking about the content and authority of Jewish law, for it is precisely through Jewish law that Judaism addresses many (but obviously not all) of the issues that matter in people’s lives. Thus in recent years the Conservative movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards has produced rabbinic letters and rulings on, for example, infertility, removing life support from a dying patient, family violence, donations of ill-gotten gains, violent and defamatory video games, providing references for schools or jobs, accommodations for the disabled, sports on Shabbat, intellectual property, and whistleblowing. All of these materials are available online to the public. The Rabbinical Assembly also published rabbinic letters on sexual ethics and poverty. We long ago solved the problem of women who cannot get writs of Jewish divorce from their husbands (agunot), an issue that still plagues most of the Orthodox world. Along with these halakhic materials of how Jewish law should be applied to our lives, there has been an engaging discussion among Conservative thinkers about the nature and authority of Jewish law, some of which I described in the 17 Conservative theories of Jewish law that I discuss in my book, The Unfolding Tradition: Philosophies of Jewish Law.

Finally, I must mention what attracted us, the Conservative/Masorti leaders, to the movement in the first place: intellectual honesty; the full integration of tradition with modernity, in which both are taken very seriously and not compartmentalized; creativity in Jewish thought, law, liturgy, music, and the other arts; and a commitment to God, Torah, and Israel in a pluralistic way that insists on respect for everyone, including those with whom you disagree. In the last several decades, the vast majority of us have added to that list egalitarianism and inclusiveness.

So what should Conservative leaders concerned with the future not only of Conservative Judaism, but of Judaism as a whole do? We should do exactly what Jewish leaders from the Bible to our own time have done, even when the large majority of Jews did not believe or act in the same way—namely, live and teach the kind of Judaism that Conservative Judaism represents with as much vigor and creativity as we can muster.

Editor’s Note: Daniel Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hope, Beauty, and Bus Lanes in Tel Aviv

From the floor of Tel Aviv's City Council, Israel's future looks more promising than many would think.

The Joy of Being Delivered from Jewish Schools Results in a Stiff Foot

Before he became a brilliant, radical, and disreputable Enlightenment philosopher, Solomon Maimon was a miserable cheder student.

Watching Game of Thrones, Waiting for Shavuot

Binge-watching the traditionless Game of Thrones while looking forward to the traditional binge-learning of Shavuot.

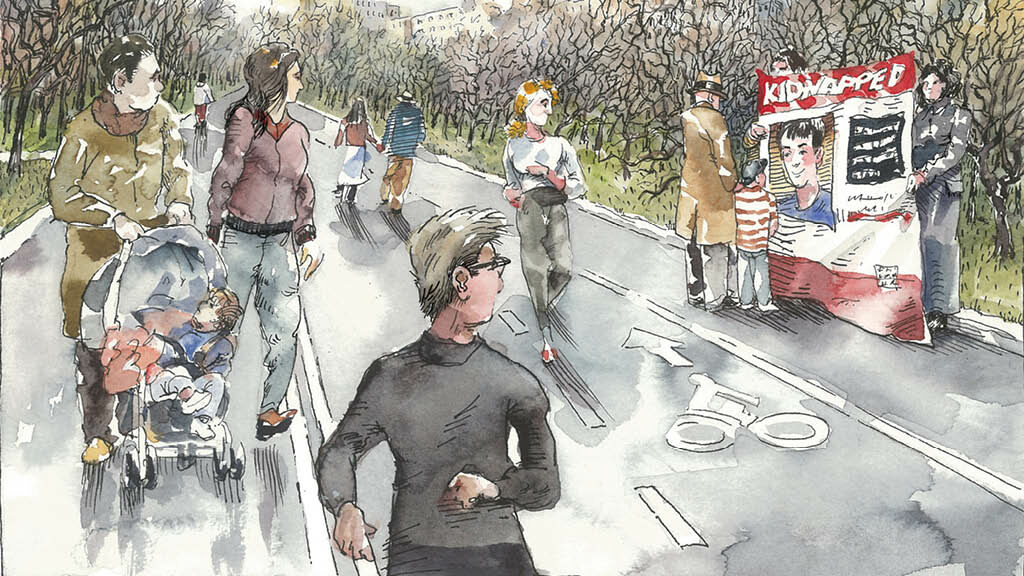

Facing Faces

Nearly every morning since October 7, I open my phone and look at the faces of the war’s most recent victims. I gaze at these portraits fearfully, searching for a…

charles.hoffman.cpa

And don't criticize

What you can't understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Bob Dylan

Rabbi Dorff's solution "live and teach the kind of Judaism that Conservative Judaism represents with as much vigor and creativity as we can muster" doesn't seem to be working. Like the Republican Party outside of the Deep South, demographics are destiny. And even as his beloved and sacred institutions of learning keep turning out conservative rabbis, their potential constituencies and congregations are ever-shrinking.

Rabbi Dorff has, for many years, a chief member of a "community of scholars", the conservative rabbinate. But as he well knows, it is all a movie set. There are edifices here and there; there are institutions which are commendably maintaining a tradition of critical thinking and insightful questioning. And yet, nobody shows up. Fewer and fewer conservative synagogues have a fully functioning minyan every day, fewer have a legitimate quorum of Jews (men and women) on Shabbat, and many of his long-time colleagues are conducting funerals at a ration of greater than 5:1 to bar/bat-mitzvahs or weddings.

So if his solution is to keep doing the same old thing but again, he'd be best off appointing that last person to "shut off the lights" (if the electric company hasn't already done the job for him.)