George Lichtheim’s Marxmanship

In the years just before and during the Second World War, a group of yekkes, immigrants from Weimar and Nazi Germany, met every Saturday afternoon at George Lichtheim’s rooftop apartment in the Rehavia neighborhood of Jerusalem. The group’s jocular name for itself was “Pilegesh” (the Hebrew term for “concubine”), an acronym formed from the first letters of the names of its members: Egyptologist Hans J. Polotsky, philosopher Hans Jonas, classicist Hans (Yochanan) Lewy, journalist and historian George Lichtheim, scholar of the Kabbalah Gershom Scholem, and historian of science Shmuel Sambursky.

Lichtheim—the youngest of the group and the only one who held no advanced university degree—gained a great deal from his weekly guests. “Condemned to dilettantism by circumstances,” Lichtheim wrote to Scholem, “I learned from you, Polotsky, and Hans Jonas what scholarship is all about.” And the young writer, born in Berlin in 1912 became, in turn, well liked. Jonas admired Lichtheim’s “superior knowledge of politics and his ironic temperament.” Scholem called him his “most worthy magic apprentice” and entrusted him with translating his groundbreaking book, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, from German into English.

George Lichtheim was to the Zionist manor born. His father’s dramatic career in Zionist diplomacy would set his horizons. Richard Lichtheim had for two years edited Die Welt, the Zionist newspaper founded by Theodor Herzl; published a definitive history of the Zionist movement in Germany; and during World War I, when Palestine still belonged to the Ottoman Empire, represented the World Zionist Organization in Constantinople. In that role, Richard got on good terms with both US ambassador Henry Morgenthau Sr. and German ambassador Baron Hans von Wangenheim and labored tirelessly to persuade the Great Powers to protect the Yishuv. In the spring of 1917, suspected of espionage, Richard returned to Berlin with his family.

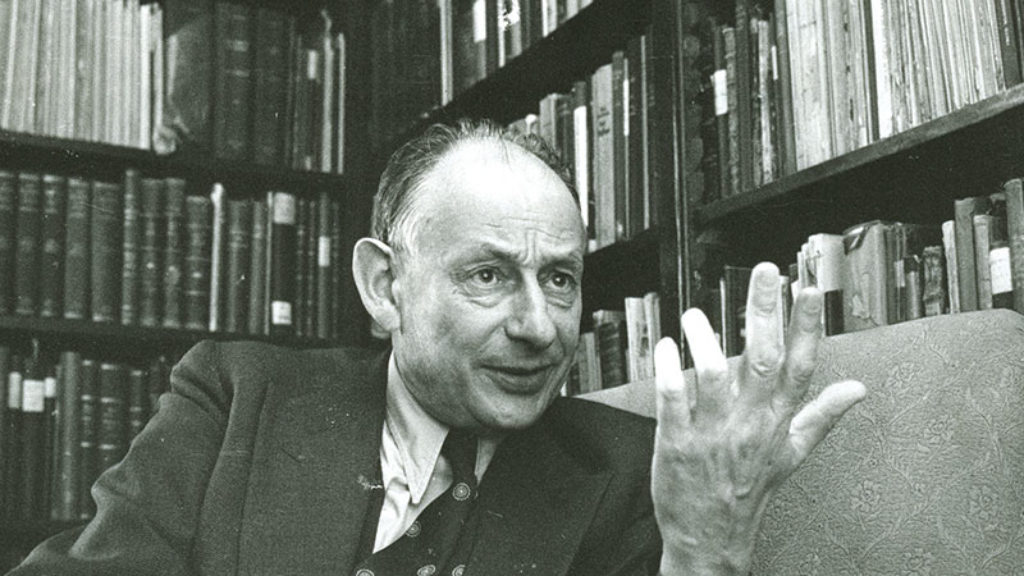

George Lichtheim, Jerusalem, 1938. (From Telling it Briefly: A Memoir of My Life by Miriam Lichtheim, 1999.)

From 1921 to 1923, at Chaim Weizmann’s invitation, Richard joined the Zionist Executive Committee in London, where he hired a governess to tutor George and his sister Miriam in English. In 1928, Richard introduced George, then sixteen, to his friend Ze’ev Jabotinsky and other leading Zionists. But the young man was already transfixed by Marxism. “When . . . I went over to the Marxist camp,” George later remarked to Scholem, “I had to suppress this Zionism in me. My father never forgave me for doing that.”

When the Lichtheims fled from Berlin to Jerusalem in the mid-1930s, George apprenticed himself to Gershon Agron, founding editor of the Palestine Post (later the Jerusalem Post), and began to write for the paper on foreign affairs. In November 1945, Agron sent Lichtheim to Nuremberg to cover what Lichtheim called “the greatest political trial in history.” In the crowded courtroom he sat close enough to the twenty defendants to observe disgraced Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s “flabby, twitching face” and the “yellow, gangster-like features” of former deputy Führer Rudolf Hess. “It becomes harder every day,” Lichtheim wrote, “for the spectator in court to infer from the looks of the accused in the dock . . . arguments in favor of the hypothesis that the Germans constitute the historical master race.”

In some ways, the revelations at Nuremberg were no surprise to Lichtheim—which perhaps explains how he was able to report on them so acutely. During the war, his father had been one of the first—if not the first—to relay reports of mass murder of European Jews. As early as the fall of 1939, Richard Lichtheim, then head of the World Zionist Organization office in Geneva, began regularly updating Jewish Agency officials (Joseph Linton in London and Leo Lauterbach in Jerusalem) on ghettoizations, deportations, and mass executions.

In November 1941, he cabled Chaim Weizmann to urge that “the great democracies should make their voice heard in connection with the latest brutalities committed against the Jews.” In August 1942, he gave Linton a country-by-country dispatch of what he even then recognized as a “process of annihilation.” Later that year, Richard Lichtheim joined Gerhart Riegner, secretary-general of the World Jewish Congress in Switzerland, for urgent meetings with the Papal Nuncio in Bern and with Leland Harrison, US ambassador to Switzerland, to transmit detailed memoranda of the ongoing genocide. All to no avail. “We have to face the fact that the large majority of the Jewish communities in Hitler-dominated Europe are doomed,” he wrote in October 1942 to Yitzhak Gruenbaum, a leader of the Yishuv and later Israel’s first interior minister. “The tragedy is too great for words.” (Andrea Kirchner’s biography of Richard Lichtheim will be published in Germany next year.)

Despite the many conversations with his father about the ongoing tragedy, Lichtheim’s two-dozen reports for the Post from Nuremberg reveal just how unnerved he still was by the mountains of details amassed during the trial of unimaginable Nazi atrocities. He reproached not just the war criminals in the dock but the intellectuals who by cultivating irrationality, reactionary romanticism, and the worship of power had infected Germans with the spiritual sickness that resulted in the Third Reich’s frenzies of hatred, in the subjugation of state and society to Hitler. These included Nietzsche and “his fascist progeny”; Oswald Spengler, “the poor man’s Nietzsche”; and Martin Heidegger, an “obscurantist” philosopher who “depraved the minds of an entire generation of university students.” “It is a myth,” Lichtheim concluded, “that the Nazi movement represented only ‘the mob.’ It had conquered the universities before it triumphed over society.” It is equally a myth, he insisted, that the defeated Germans felt sorry for their crimes. “In prosaic fact,” Lichtheim said, “most of them are sorry only for themselves.”

His pieces for the Post splashed into widening circles of esteem. One reader, future Israeli prime minister Moshe Sharett, wrote to Gershon Agron from his cell in the Latrun prison: “A special request for you: convey my blessings and my admiration to G.L. . . . In him are joined intelligence, seriousness, and talent; an unsurpassed penetrating precision and striking power.”

Yet Lichtheim chose not to return from Nuremberg to Jerusalem. In part, as he would later remark, the choice owed something to disillusionment:

The fundamental fact about Israel . . . is the radical incompatibility of its daily life with the aspirations of the Zionist movement from which it was born. Like Communism in Russia, Zionism in Israel has become a hollow shell, the ideological remnant of a buried East European past.

The Israeli state, in his eyes, had failed to accommodate a sense of Jewish belonging and culture.

Two decades after Nuremberg, Lichtheim would write to Scholem:

As I often recall my years in Jerusalem I from time to time ask myself whether it was not a mistake to have left. It is undeniable that in your country one at least does not have that feeling of being “in a foreign land” which is unavoidable here. In the end I too departed because only here could I do my real work.

“Here” was London, where Lichtheim found lodgings on the top floor of the Hampstead home of the eminent historian of fascism Francis L. Carsten, not far from where Karl Marx had lived a century earlier. Put off by British provincialism, Lichtheim struggled at first to find his bearings. “Foreigners—Americans, Russians, Europeans—went on making history,” he said, “while the BBC duly reported on the doings of the Royal Family and the latest score in the England-Australia cricket match.” Nor did the outbreak of antisemitic disturbances in postwar England, which he described in a 1948 Commentary essay, endear the country to him.

Lichtheim, who joined the Fabian socialists, was neither a Cold War liberal nor an early neocon (though the Oxford English Dictionary credits him with coining the term “neoconservative” in 1960). Ever the individualist, he held himself aloof from university life. Convinced that “a new doctrine becomes academically respectable only after it has petrified,” he never sought the coziness of academic respectability. He supported himself as a freelance writer, sometimes under the pen name G. L. Arnold, for Partisan Review, Encounter, the Times Literary Supplement, the New York Review of Books,and Commentary. His essays grappled, among much else, with literary figures (Simone Weil and Thomas Mann), British politicians (Churchill and Disraeli), the ugly entanglements of anticapitalist and anti-Jewish hatreds, and the concept of ideology.

In these essays Lichtheim honed his skills as an interpreter of central European thinkers for an Anglo-American readership, but also as a controversialist who gave as good as he got; he salted his prose with an implacable rudeness that increased his quotient of quotability. Eric Hobsbawm, Britain’s most distinguished Marxist historian, commended Lichtheim as a “great practitioner of intellectual contempt.” Leading Hungarian Marxist Georg Lukács, for instance, to whom Lichtheim addressed a book-length study in 1970, “has not merely failed to write the Marxist aesthetics his admirers expected from him: he has failed altogether as a responsible writer, and ultimately as a man.”

He was equally critical of anti-Marxists. In Lichtheim’s view, “when he comes to areas outside the United States,” the American sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset “does not know what he is talking about.” Cold warriors who parroted CIA director Allen Dulles’s simplistic phrasemongering about the East versus the West were purveyors of “Dullesian drivel.” And the political philosopher Leo Strauss subjected himself to Lichtheim’s ridicule for referring “to atheism with horror, as though it were some kind of obscene disease caught by infection, instead of being the characteristic attitude of modern man.”

For a short time in the late 1950s, Lichtheim decamped to New York and jointly edited Commentary with Norman Podhoretz and Martin Greenberg, who were not on speaking terms—“not an ideal way of running a magazine,” Lichtheim quipped to Hannah Arendt. This was when he attracted the interest of Susan Sontag, “the top-booted girl who wandered around the Village with me in the rain . . . the elegant young woman whom I was then permitted to escort to fashionable restaurants.”

Sontag’s flirtation with Lichtheim would prove as brief as her flirtation with Marxism. Lichtheim, by contrast, had long looked to Marx, in his words, as “a colossus in the midst of ordinary mortals.” As the Cold War reached its peak, he pondered a question that would turn into a lifelong preoccupation: what is salvageable of Marx, when the movement he inspired went morally bankrupt, when the working classes not only waged war for nation states (in World War I) but lent their support to fascist revolution (in the Third Reich)?

From left to right: Hans Lewy, Miriam and George Lichtheim, and Hans Polotsky in Jerusalem in an undated photo. (Courtesy of the Gershom Scholem Archive, National Library of Israel.)

In 1961, Lichtheim completed his breakthrough book, Marxism: An Historical and Critical Study. It told the story, as he put it, of “the Marxist movement from its inception in 1848 to its petrifaction a century later.” More than four decades later, the historian Tony Judt wrote that the book remained “the best single volume study of Marxism.” Lichtheim followed it with a prequel, The Origins of Socialism, a compact history of the movement from the French Revolution to its apex with Marx.

Lichtheim read Marx less as a thinker who prefigured the Russian Revolution than as a product of the French and German intellectual traditions. Hegel and other Germans “were caught up in the Lutheran disjunction of Spirit (internal) and the world (external).” By overcoming that disjunction, Lichtheim argued, true Marxism “represents a revival of the Hebraic strain within the European tradition”—a “prophetic eschatology” that played a vital role in “transferring to an uncertain future the ancient vision of a world set free.”

As a historian of Marxism and interpreter of its ruins, Lichtheim defended that vision on two flanks. On one side, he battled against self-styled Marxist radicals on the New Left. “In California, one gathers, it is now established ground among the more advanced spirits that Marx was a forerunner of both psychoanalysis and Zen Buddhism,” Lichtheim wrote. “No one in the past decade,” American intellectual historian Martin Jay wrote in 1973, “has done more to enlighten the English-speaking world about the history of both Marxist theory and the socialist movement than George Lichtheim.” On the other side, Lichtheim defended the author of Das Kapital against critics “eager to make Marx appear as the progenitor of everything they happen to dislike.”

Among those who appreciated these maneuvers was the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, who in 1968 began corresponding with Lichtheim about the Marxist social theory elaborated by Horkheimer, Adorno, and other members of the Frankfurt School. Among the less appreciative was the British philosopher Maurice Cranston, who attacked Lichtheim’s “defensive attitude to Marxism. . . . Since he is certainly no regular soldier in any Party formation, is he not to be understood as an irregular or guerrilla fighter for the cause?”

If Lichtheim can be said to have fought as an intellectual irregular, he did so in the anti-Communist cause. He bemoaned how “Marxism in Russia became a creed,” a secularized theology that offered the regime a good conscience. He insisted that in its eastward shift, Marx’s political program had been travestied by the Soviets’ freedom-suppressing impulse to refashion society, “perhaps the most ‘un-Marxian’ notion ever excogitated by professed Marxists.” Soviet despots thereby turned a theory of history, said Lichtheim, into “the ideology of a ruling caste convinced that it has got history under control.” In short, Soviet Communism became “identified with a set of beliefs which Marx would never have dreamed of putting forward.”

By tone and temperament, Lichtheim remained all his life a “fiercely independent” outsider, as his friend Irving Kristol called him, unbeholden to any party line. Israeli political scientist Shlomo Avineri said that Lichtheim personified “the perpetual pilgrim, the committed yet alienated intellectual, the Wandering Jew.” Few doubted his finely calibrated mind. But because his writings defied the usual categories, his friend Walter Laqueur observed, “Lichtheim never achieved the kind of vogue that came the way of a number of political thinkers in the 50’s and 60’s, despite the fact that he was intellectually superior to almost all of them.”

This uncompromising independence, joined to an atheist’s fixation on mortality, helped induce melancholy and loneliness. In a letter to Scholem, Lichtheim wondered “whether humanity, with messianism and the belief in eternal life now behind it, will in the long run be able to endure the fact that life is of limited duration.” When a woman with whom he had rekindled a romance died of cancer in 1970, his bouts of depression and insomnia grew increasingly severe.

In January 1973, after a botched suicide attempt, he assured Scholem that the try “won’t be repeated.” On April 21, he wrote to Podhoretz: “Sorry to have let you down, but the fact is I have written myself out and can do no more.” The next day, Lichtheim, sixty-one years old, took his own life in his furnished rooms in the Carsten home.

The fiftieth anniversary of George Lichtheim’s untimely death occasions a chance not only to take the measure of a writer who has fallen into unmerited neglect but also to remind us of our need for more independent-minded skeptics about political ideology. All his life, Lichtheim brought the clamorous ideas of the nineteenth century to bear on the crimes—and tragic complacencies—of the twentieth. In the attempt to make the world intelligible, each generation devises its own blinkers. Ours may make it hard to recognize what a twenty-first century Lichtheim might look like. In the meantime, we can still reread Lichtheim himself.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Many Dybbuks of Romain Gary

Romain Gary—a Lithuanian Jew who regarded himself a Frenchman par excellence—emerges in a recent memoir as a master of self-invention and (just as immoderate) verbal invention, a chameleon of pseudonyms, a man of irreconcilable contradictions, divided against himself.

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

Marx and the Jewish Fingerprint Question

Are there hints about Marx’s thoughts on Judaism in his writing, and if so, what do they say?

Psychology at Nuremberg

Both Kelley and Gilbert believed they could make a broad psychosocial argument despite the limited sample size, inconclusive tests, infighting, and lack of clear standards and definitions.

Mark Simon

Nearly three decades ago, Gary Smith and I proposed to publish the correspondence of George Lichtheim and Gershom Scholem. Gary wrote to Miriam Lichtheim, George’s sister, who incidentally was a distinguished Israeli Egyptologist, suggesting the project and requesting permission to reproduce the correspondence. She refused on the grounds that her brother would never have allowed private matters, including his health and mental anguish, to be made public in this way.

I see from Benjamin Balint’s very welcome article that this correspondence has been quoted, and I wonder if the complete correspondence is now being studied, and perhaps even considered again for publication. I still think it would be a valuable publication.