What We Talk About When We Talk About Stepan Bandera: A Rejoinder to Dovid Katz

Dovid Katz has had a long and distinguished career in reestablishing Jewish learning and Yiddishkeit in Lithuania and in fighting Shoah revisionism and denial across Eastern Europe. He deserves ample credit for both, so it is especially disappointing when he adopts, in his response to my article, the position that his—and our—enemies are his friends. “In other words,” he writes, “when it comes to the basic ethical issue of how we think about the Nazis and their local reliable killers, the bad guys are the good guys and the good guys are the bad guys.” Vladimir Putin, his allies in the Baltic states, and the eastern Ukrainian separatists are the “the good guys” in their rejection of an anti-Semitic Nazi collaborationist past, while the Ukrainian nationalists are “the bad guys.”

It would be easy to use the shooting down of flight MH17 over Donetsk—which occurred after Katz had written his comments but before I had the chance of penning this reply—to rebut him. But even though it is all but certain that the “antifascist” separatists and their Russian patrons are guilty of this heinous crime, this does not affect Katz’s main argument; easy does not necessarily mean fair.

The reason that I miss the crucial moral and political distinction between Ukrainian nationalists and Russian-supported separatists, Katz argues, is that I am blinded by the example of my own country. The Jewish gamble to support the Polish democratic nationalist movement in the 1980s paid off, he suggests, because, unlike western Ukraine and the Baltic states, Poland’s patriotic tradition does not include heroes who were Jew-killers. However, supporting the democratic nationalist movement in Ukraine means supporting those who, to say the least, do not mind that their heroes were, in fact, Jew-killers who collaborated with the Nazis, which should be unacceptable not only to Jews but to all decent people. The monuments erected all over Western Ukraine to Stepan Bandera, he says, prove his point.

Katz is largely right when he says that the Polish democratic tradition is far richer and more developed than that of the nations east of it. But this did not prevent monuments to decidedly unsavory characters being built after the fall of Communism. Roman Dmowski, the leader of the interwar National-Democratic Party and Poland’s successful negotiator at Versailles, was a rabid anti-Semite. His monument stands next to the prime minister’s office in Warsaw; it is the focal point of all extreme-right demonstrations. And Józef Kuraś, a partisan who fought the Germans during World War II and then the communists after briefly throwing in with them, is mainly remembered as killer of Slovaks and Jews on the country’s southern border. His monument was unveiled by then-President Lech Kaczyński in Zakopane in 2006. Kuraś was not as bad as Stepan Bandera, who was responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands in the Ukraine, but the line is thin.

This is not to damn Poland, but simply to indicate that countries tend to integrate their past, such as it is, into collective memory. Both the Dmowski and the Kuraś monuments have been amply criticized in Polish public debate; today, they are remembered as controversial heroes. Had they not been thus recognized, they would be remembered by many as men whose heroism was suppressed and whose memories had been trampled. This would have been less, not more, conducive to the acceptance of criticism of their actions.

Katz is wrong, however, to imply that eastern Ukrainian separatists would embrace the democratic values of the EU and membership in NATO if only the western Ukrainian fascists had not hijacked that noble cause. In a May 2014 poll, conducted by the Ukrainian company SOCIS, slightly over 50 percent of Ukrainians supported joining the EU, while 31 percent preferred Moscow’s Custom Union. This is a legitimate disagreement, since EU membership will put a heavy burden on the country’s economy. As for NATO, a Razumkov Centre poll in April showed only 37 percent in favor of joining, with 42 percent opposed. Who knows what the numbers are now, but it is clear that NATO membership would heighten tensions with Russia yet further. Both issues are for Ukraine to decide through its democratic institutions, not by force of arms.

It is wrong to pretend that the Ukrainian separatists are democrats-in-waiting with antifascist scruples, but it is even more wrong to paint the rest of the country as nostalgic for the far-right fascism of Stepan Bandera. In the presidential elections of May 2014, the only two candidates of whom this could be said were Dmytro Yarosh of Pravy Sektor (Right Sector) and Oleh Tyahnybok of Svoboda (Freedom). As I noted in my original article, together, the two candidates polled just 1.76 percent of the vote. This was notwithstanding all the legitimate credit their organizations had gained in the bloody defense of the Maidan in Kiev against the goons of then-President Viktor Yanukovych (who was not a “good guy” even if he did annul Bandera’s posthumous “Hero of Ukraine” award). Meanwhile, another marginal candidate, businessman Vadim Rabinovich, whose sole public salience was his presidency of the Ukrainian Jewish Parliament, scored 2.25 percent. Even if one were to assume that all Jewish voters (0.25 percent of the total electorate) chose Rabinovich (they didn’t), this would still leave 2 percent of the electorate who voted for a successful Jew, while 1.76 percent voted for candidates opposed to Jews, successful ones in particular.

All this, of course, offers no guarantee that Ukraine will emerge democratic, with a safe and thriving Jewish population. But the example of Poland—which 25 years ago enjoyed a reputation no better than that of Ukraine today—shows that it is a distinct possibility.

What are the other options? In Belarus, Katz writes Jewish veterans of World War II are honored in “town-center monuments to the Red Army’s defeat of the Hitlerite invaders of 1941–1944 . . . while the Nazis and their local collaborators in genocide continue to be held in utter contempt.” True, but one needs to remember that these monuments first honor the Red Army’s defeat of the Polish Army in 1939, when the USSR was an ally of Hitler—and that Jewish war veterans are honored in Ukraine as well. Meanwhile, the alleged contempt in which Nazis are held in Belarus is somewhat mitigated by the occasional comments of its Stalinesque dictator, President Alexander Lukashenko. Lukashenko has said that “not everything connected with . . . Adolf Hitler, was bad. German order evolved over the centuries and under Hitler it attained its peak” (Russian television interview, November 1995). A few years ago he remarked that “Jews are not concerned for the place they live in. They have turned Bobruisk into a pigsty. Look at Israel—I was there” (Belarus State Radio, October 2007). Small wonder that levels of anti-Semitism in Belarus were, according to a 2008 European Values Study survey, higher than in Latvia, Ukraine, Russia, or Poland (but lower than in Lithuania).

Luckily, Lukashenko dislikes his opponents more than he does Jews, which keeps the latter safe for now. The laudable antifascism of Belarus and Russia depends, in both cases, on a dictator’s whim. It is true, of course, that the rejection of fascism by democratic countries depends upon public opinion, but as whims go, I’ll take the latter—even if the danger of fascism in Ukraine is greater than it is, say, in the UK.

Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany were not the same, as Katz rightly argues. But, as he seems reluctant to admit, they were both genocidal dictatorships. A comparative discussion would require more space than I have here, nor would it really pertain to the issues at hand. Does expressing a relative preference for one of these historical monstrosities over the other imply wholehearted contemporary endorsement? If so, then Katz is right in claiming that present-day Ukrainians who admire Bandera necessarily accept and endorse all that he said or did, including the mass murder of Jews and Poles (even though Bandera himself eventually gave up on mass murder, broke with the Germans, and ended up their prisoner in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp). But it would also mean that Dovid Katz, who lauds the antifascist victories of the Red Army, also retrospectively approves of the bloody pacification of Ukraine, the occupation of the Baltic States, the Gulag, and ultimately Stalin himself.

This would, of course, be unfair. Dovid Katz is no Stalinist, though I am sure that he has been called that by some of his Eastern European critics. But this same sense of fairness requires us to ask why those Ukrainians who celebrate Bandera do so. Is it because he ordered the killing of Jews and Poles or because he attempted to set up an independent Ukraine? What, in short, do we talk about when we talk about Stepan Bandera? Unless we ask the question with an open mind, we’ll never know the answer.

Suggested Reading

Getting Out from Under: The Philip Roth Story

“I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting,” Philip Roth told his biographer. Has he?

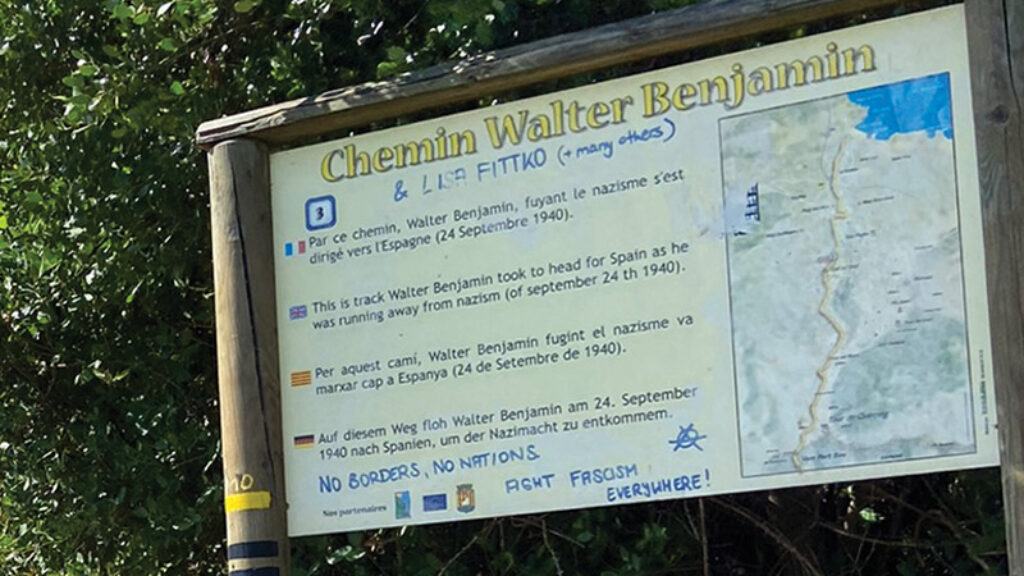

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

Athens or Sparta?

A new "inside story" of the Israeli military reveals more about the current prejudices of the chattering classes than it does about Israel and its neighbors.

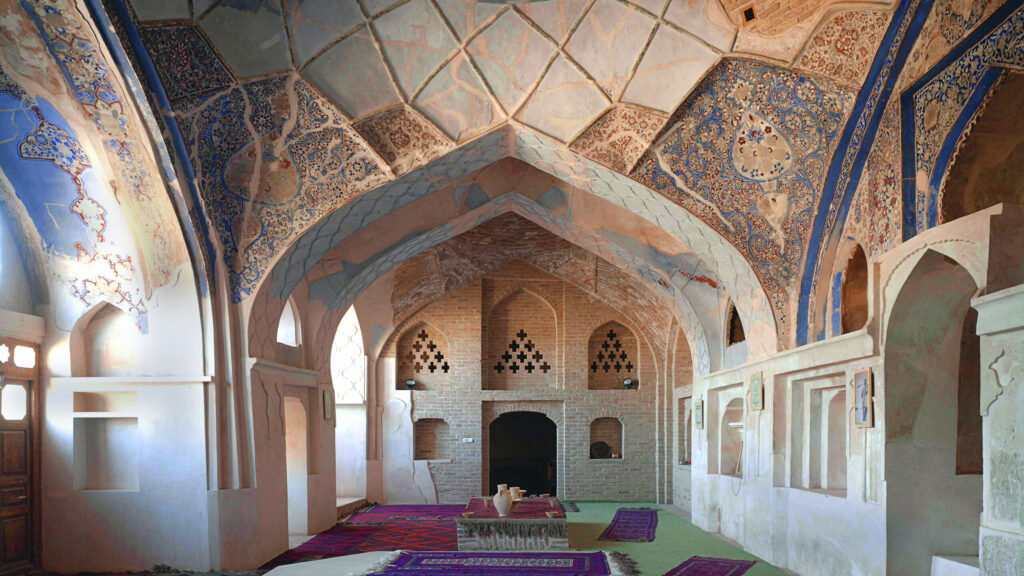

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In