From King James to Koren

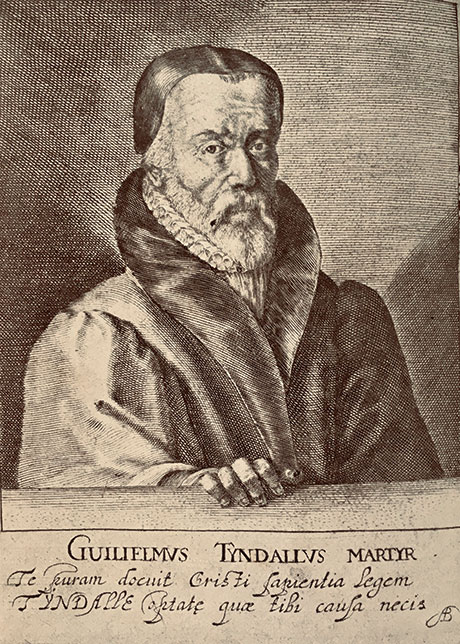

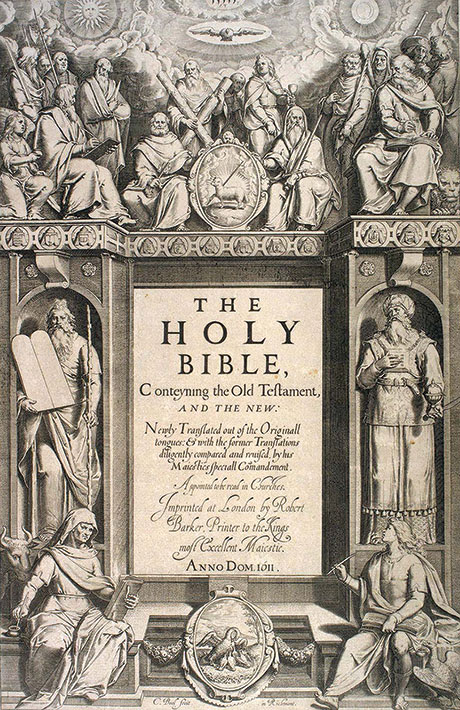

In the beginning, there was William Tyndale’s Bible, and it was good. Tyndale died at the stake for his efforts, but his sixteenth-century English translation from the Hebrew begot nearly all the others, most famously the 1611 King James Version. The King James eventually begot various Jewish translations. In 1845, Isaac Leeser, the Philadelphia-based communal leader and writer, lamented Jewish reliance on “a deceased King of England, who was certainly no prophet, for the correct understanding of the Scriptures,” yet these words were written in the introduction to his own King James–inspired translation. In 1881, Michael Friedlander published the Jewish Family Bible, which amounted to the King James minus the Christology.

Even the celebrated 1917 translation by the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) was really only a light revision of the King James rather than a wholly original work. The original JPS translation was adopted by the 1936 Hertz Pentateuch, which was then used by English-speaking synagogues around the world for half a century. In short, Jews were satisfied with the King James for quite some time. While its English is decidedly archaic, it is quite faithful to the original, preserving much of the syntax and rhythm of the Hebrew.

It was only in the latter half of the twentieth century that wholly new translations appeared. Between 1962 and 1985, JPS published a new translation (NJPS) with a team of academic scholars working more or less from scratch. It was meticulously researched and more concerned with Modern English idiom than word-for-word equivalence with the Hebrew—less “formal” and more “functional,” as scholars often put it. Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s The Living Torah broke new and rather different ground in the 1980s with its Orthodox approach and colloquial style (yom ha-sheviyi, the seventh day, sometimes became “Saturday”). Meanwhile, ArtScroll’s 1996 Stone Edition Tanach sought word-for-word correspondence. ArtScroll’s fidelity to the Hebrew syntax sometimes led to choppy translation. On the other hand, its reliance on Rashi’s midrashic approach made some of its renderings less literal. In 2018, after more than two decades of labor, Robert Alter completed a translation exhibiting profound literary sensitivity and an ear for the poetry of the Hebrew language, though his translation also has its critics, from John Updike to biblical philologists.

The Koren Tanakh Maalot, Magerman Edition, a complete Hebrew-English Bible from Koren Publishers Jerusalem, thus enters a crowded field, but it does so with an interesting pedigree. In the 1950s, Eliyahu Koren, living in the newly constituted State of Israel, ambitiously prepared the first edition of the Bible created entirely by Jews down to the layout and the binding. But Koren was less trailblazing when it came to the work’s English translation, which was just a version of Friedlander’s Jewish Family Bible, updated by literary critic Harold Fisch. The translation distinguished itself from the King James mainly in its use of transliterated Hebrew names such as “Moshe” instead of the more common “Moses.” The new translation is completely reimagined, reads smoothly, and is not unlike the NJPS in its willingness to depart from literal translation. It is the work of a team of translators and academic reviewers, and it is particularly notable that other than the late Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks (who translated the Pentateuch) and Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb of the Orthodox Union, all the other translators are women, including Jessica Sacks (Jonathan Sacks’s niece). Also of note, Dr. Will Lee, professor emeritus of English at Yeshiva University, served as the literary editor. The result is a crisp, contemporary, and thoroughly readable translation.

Take the Koren translation of Ecclesiastes, among the most confounding books of the Bible. One of the central words is hevel, translated by the King James as “vanity” (“Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity”) and NJPS as “futility.” Both are reasonable choices; futility sounds more modern and perhaps less morally freighted than vanity. Yet either way, Kohelet is saying that he tried many things and they all amounted to naught.

In the Magerman Tanakh, Jessica Sacks follows Robert Alter in translating the word as breath, mere breath, or fleeting breath. The advantage, as Alter points out, is that hevel literally means “breath,” or “the flimsy vapor that is exhaled in breathing . . . immediately dissipating in the air.” Breath is a physical metaphor for insubstantiality rather than a kind of psychological paraphrase like futility and, thus, more faithful to the way Hebrew metaphor tends to work. Also, breath emphasizes the temporal aspect of the narrator’s quest. Since, for Kohelet, there is indeed a time for everything under the heavens, the problem with wisdom, riches, and pleasure is not so much that they are futile but that they are ephemeral. Hevel implies a temporary satisfaction that slips through one’s grasp as rapidly as breath is expelled from one’s lips. (Sacks’s use of the adjectives mere and fleeting to qualify the single biblical word breath/hevel are less defensible.)

The Koren translators also pay great attention to the sound quality of English words. In an interview on Koren’s podcast, Sacks gave the example of the woman from Song of Songs. After the maiden tarries in opening the door for her beloved and he slips away, she laments, “hamu me’ai alav,” which the King James unselfconsciously translates as “My bowels were moved for him” (5:4). Although me’ai literally refers to the digestive system, the metaphor falls flat (or worse) with modern readers. The 1917 JPS Tanakh updated it to “my heart was moved for him,” but Sacks wanted to capture the sound made by the Hebrew words and settled on “my being longed for him,” which expresses the woman’s overpowering feeling of unrequited love and, with its long vowels, partly echoes the sound pattern of the original.

Although Koren’s new translation is largely literal, it is still less formal than older ones. In her translation of the book of Esther, for example, Jessica Sacks takes small liberties with the Hebrew to capture the passion and surprise of the characters when Haman’s treachery is revealed. When Haman is nofel (7:8), begging for his lifeon Esther’s couch, he does not merely “fall” but is described as having “thrown himself” upon it. Achashverosh’s reaction, vayomer ha-melekh ha-gam likhbosh et ha-malkah imi ba-bayit, becomes, “‘What!’ said the king. ‘Would you take the queen too, and with me in the palace?!’” Notice the difference in tone between this and the slightly more literal, but blander, 1917 JPS translation, “Then said the king: ‘Will he even force the queen before me in the house?’” Moreover, in Sacks’s translation, unlike all others I examined, Achashverosh speaks to Haman, not just about him. (Speaking of departures from literal meaning, instead of “an eye for an eye” (Ex. 21:24), Jonathan Sacks translates “the cost of . . . an eye for an eye.” A footnote tells us that “the translation follows the rabbinic interpretation.” Even ArtScroll, a champion of rabbinic exegesis, does not go so far.)

The Koren translators have also clearly drawn upon contemporary academic scholarship. Take, for instance, the tahash skins used by the Israelites in the tabernacle (Ex. 25:5). Earlier translations have given us a biblical bestiary, from the King James’s badgers to NJPS’s dolphins to the Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon’s porpoises. Even the narwhal and unicorn have been suggested, while ArtScroll simply leaves the word untranslated. In the Magerman Edition, Jonathan Sacks translates orot tehashim as “fine leather,” which hews closer to some recent—although not undisputed—scholarship suggesting that tahash was not an animal at all but a kind of leatherwork or leather embroidery.

The introduction to the Magerman Tanakh provides a brief history of printed bibles, and the back matter includes a wealth of genealogies, maps, renderings of the Temple, and descriptions of archaeological artifacts. Dictionary tabs allow one to locate each biblical book with ease. Despite the volume’s impressive ambitions, it’s compact and easy to read. This suggests that it targets both scholars and lay readers, albeit ones who can benefit from seeing the Hebrew and English side by side. Still, given the plethora of recent Bible translations, it’s worthwhile to consider Koren’s target audience. Although the volume is not pitched as a parochial project, it follows Koren’s other recent biblical commentaries and companion books that primarily appeal to a Modern Orthodox audience. As an implicitly Modern Orthodox work, the Magerman Edition is simultaneously a response to the non-Orthodox scholars of NJPS and to ArtScroll’s translation, which is a product of a more traditionalist Orthodox worldview.

Koren’s approach differs noticeably from ArtScroll’s in several respects. Famously, ArtScroll only translates Song of Songs allegorically, basing itself on Rashi’s interpretation and claiming that the “literal meaning of the words is so far from their meaning that it is false.” Koren has no such compunctions in this regard and translates the book literally. (In Song of Songs 4:5, for example, the man refers to his beloved’s “two breasts,” which Koren translates literally, but ArtScroll renders as “Moses and Aaron,” the “two sustainers” of Israel.)

Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz, ArtScroll’s founding editor, wrote in the introduction to ArtScroll’s first work, a commentary on Esther, that “no non-Jewish sources have even been consulted, much less quoted. I consider it offensive that the Torah should need authentication from the secular or so-called ‘scientific’ sources.” But the Magerman Edition includes full-color displays of archaeological finds, and the publishers consulted with many university-trained scholars to prepare the volume.

The differences between Koren and NJPS are more subtle and are, in part, due to their differing approaches to biblical criticism. In 1953, when work on the NJPS translation began, Dr. Solomon Grayzel, the editor of JPS, wrote to Rabbi Theodore Adams, the president of the Rabbinical Council of America, to request the group’s participation in the project. Adams, in turn, wrote to Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the leading intellectual figure at Yeshiva University, who instructed Adams to refuse due to his concerns about biblical criticism. Nonetheless, many Modern Orthodox Jews have quietly embraced the translation over the years.

The Magerman Edition is circumspect when it comes to issues touching on textual criticism. For example, in the Akedah passages, after God instructs Abraham not to sacrifice his son, Abraham finds ayil aharne’ehaz ba-sevakh be-karnav

(Gen. 22:13), a ram caught in a thicket by its horns. The word ahar is strange here, for it typically means “afterward.” After what, though? ArtScroll’s translation, that Abraham “saw—behold, a ram!—afterwards, caught in the thicket,” is awkward. NJPS, footnoting other manuscripts of the biblical text that have ehad—“one”—instead of ahar, translates, “a ram, caught in the thicket.” In the Magerman Edition, Rabbi Sacks’s translation matches NJPS’s, but no footnote identifies the divergent manuscripts. The Koren Tanakh thus charts a middle path between ArtScroll and NJPS, perhaps reflecting a Modern Orthodoxy now willing to accept the findings of the academy piecemeal, although not wholesale. Thus, Koren’s recent illustrated The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel addresses historical questions about the dating of the Exodus from Egypt despite acknowledging that it is unable to reach a fully satisfactory conclusion. Such a book would likely not have been written for a Modern Orthodox audience a decade or two ago.

Does it matter that the Magerman Tanakh is a Modern Orthodox work? Perhaps not, especially since it wears its agenda lightly. However, it does seem to be part of the recent movement toward niche bibles, which Dr. Paul Gutjahr has documented with respect to Christian editions. ArtScroll’s Stone Edition Tanach is representative of this trend. So is JPS’s 2006 gender-sensitive adaptation of its Chumash translation, The Contemporary Torah, which is used by the Reform Movement. The 2015 Chabad-Lubavitch

Kehot Chumash goes even further, inserting many midrashic explanations into the translation itself, albeit in a different typeface. Koren’s Magerman Edition, which is part of this trend, would seem to be aimed at an audience that takes a traditional Jewish attitude toward the Bible but also wants to respect the results of modern academic scholarship.

Arguably, we are the richer for the recent proliferation of English Bibles. The King James Version and its progeny may have provided a shared biblical idiom for Christians and Jews of all stripes, but those versions papered over real differences. To many Christian readers, Isaiah prophesizes the coming of Jesus. For some Jews, midrashic homilies are inseparable from the biblical text. For others, it is anathema to ascribe a gender to God. The Hebrew text of the Bible will remain unchanged, but as long as the different interpretations cannot be represented in a single work, it is not such a bad thing to have choices.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Brave New Bavli: Talmud in the Age of the iPad

The Talmud was hypertextual before we had the word. ArtScroll's new app is only the beginning.

Lost in Translation

The novelist Jonathan Rosen has written evocatively of the parallels between rabbinic literature and the World Wide Web: “When I look at a page of Talmud and see all those texts tucked intimately and intrusively onto the same page, like immigrant children sharing a single bed, I do think of the interrupting, jumbled culture of the Internet.” Rosen’s insight is…

Torah U’Madda

Only 3 percent of American Jews are Modern Orthodox, but that number belies the movement's diversity.

Korean Talmud, Is Modern Orthodoxy like Classical Reform? and Jesus and the Baal Shem Tov

A round-up of three new and notable articles in Jewish studies.

JJ Gross

Artscroll's translation is agenda-driven to the degree that it can only be taken seriously by someone who buys into the yeshivish-haredi agenda which eschews both a feeling for words and a literal reading of text. Their absurd translation of Shir Hashirim is an over the top example not only because it denies the literal, but because it manifests a total recoiling from the beauty of the metaphor's inspiration. Perhaps a more amusing example of Artscroll's detachment from reality for the sake of a misguided 'tznius' is in the story of the Judgment of Solomon (Kings ! 3:16) in which the two women are described as "shtei nashim zonot". While the Magerman translation is honest and literal, i.e. "two harlot women", Artscroll translates this as "two women innkeepers". In order to achieve this tour deforce of farfetchery, Artscroll abused the Aramaic translation of Yonatan ben Uziel, which calls them "nashim pundakaiyot", i.e. women of the caravanseries. Then as now the oldest profession plied its trade where the truckers bedded down for the night. Surely Targum Yonatan never imagined that anyone would deliberately misunderstand his turn of phrase in order to serve an agenda of censoring the schmutz out of TaNaKH.