A View from Reservoir Hill

I live in Baltimore, in a neighborhood that was once the Old Jewish Neighborhood but aspires to become the New Jewish Neighborhood. Now called Reservoir Hill, it unites what used to be two communities: Eutaw Place, the grand boulevard with its elegant town homes, and Lake Drive, which included several blocks east of Eutaw with more modest row houses. African-Americans have for decades constituted the large majority of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, but in recent years Reservoir Hill has become an increasingly diverse community, a rarity in Baltimore, one that includes more and more Jewish families.

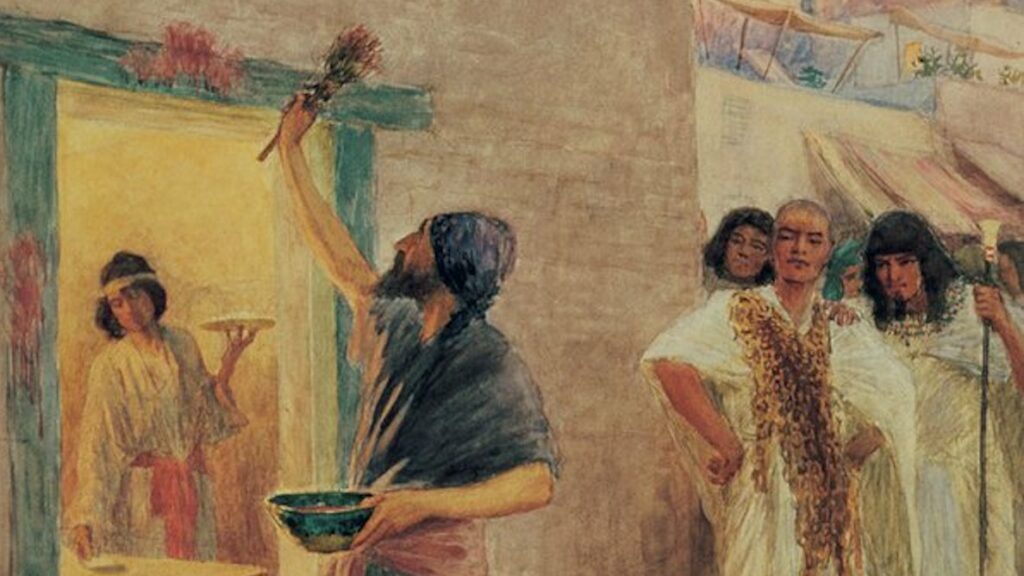

For the past five years, I have served as rabbi of Beth Am Synagogue, a 40-year-old shul in a 93-year-old building. Beth Am tries to deepen the connections between our members and our mostly non-Jewish, African-American neighbors. Last year, in January, we packed over 350 people into our social hall to hear and dance to the rhythms of a terrific, eclectic jazz band called the Afro-Semitic Experience. On Sukkot, near our community’s urban farm, we cosponsored a greens-and-kugel cook-off and ecumenical lulav and etrog demonstrations. Such events may not repair the world, but they are, at least, acts of tikkun shechuna—they repair the neighborhood, softening boundaries, and, perhaps in some small way, restoring bonds that were broken or strained decades ago.

Our synagogue isn’t in the neighborhood that made headlines last month, but we are close. The shocking death of Freddie Gray after his short trip down nearby streets in a police van on April 12 hit many of us quite hard. After shul, on Shabbat morning April 25, I joined some members of the congregation to walk one mile west and meet up with Jews United for Justice and our black neighbors. Together we marched through the streets of west Baltimore, picking up additional protestors along the way. Eventually our group and others converged on City Hall. By the time I got back to Reservoir Hill, I had walked about seven miles and, even though I knew that I was a far cry from Selma in 1965, I thought of Heschel and felt like my “legs were praying.”

Two days later, however, it was less the civil rights marches of the 1960s that were on our minds than the urban riots of that decade. Measured by the standards of the Baltimore riots of 1968, what happened this year was pretty tame. But that wasn’t clear from the outset, and many people were frightened when things heated up on April 27. Others were more frustrated and angry than afraid. I saw early evidence of this when I got into a conversation with my African-American neighbor Brandon, who runs a junk delivery business, soon after teenagers began to square off with the police. I had been outside, watching the helicopters circle overhead, when he pulled up to the curb in his truck. The junkyard, he told me, had closed early on account of the unrest. His truck was full because he couldn’t drop off his load, which meant he wouldn’t be able to do his scheduled pickups the next day. “I’m gonna lose a few hundreds dollars because of those stupid kids,” he complained. “I can’t afford that!”

Baltimore as a whole lost millions that night, as over two hundred businesses were looted and large inventories were burned. But no lives were lost, and we shouldn’t lose perspective. It was not a race riot. The perpetrators of violence didn’t seem to see whites in general as their enemy, nor were they targeting homes or individuals. Our residential neighborhood was untouched by the events of that night. For the fact that there was no loss of life on April 27 the Baltimore police—not exactly heroes of the moment—deserve a lot of credit. While I have deep misgivings about some police practices, I believe that we owe a debt of gratitude to these men and women who behaved with restraint in the face of great provocation. Properties can be revived from the ashes. People cannot.

The looters and rioters on Monday night were far fewer in number than the thousands who came out on Tuesday morning to clean up the damage. My wife and I saw this for ourselves when we decided to postpone taking our kids to school and to go first to nearby Sandtown to join scores of other volunteers to clean up. We were young and old, local residents and others, black, white, and brown, wielding push brooms and garbage bags. At one point, a group of us stopped in front of a looted corner store and prayed. “This is not a time to tear down; it’s a time to build up,” I said, paraphrasing Kohelet. What our group was trying to rebuild there was a large urban farm with rows of hoop houses covered in plastic. One section was right next to a car that had been burned, and the plastic had melted onto the produce. We ripped out the damaged crops and replaced the plastic.

On Tuesday evening, a few of us drove over to join hundreds of other clergy and thousands of worshipers at Empowerment Temple Church. When we arrived, they were reaching the end of a lengthy session of testimonials offered by young black men who had been harassed by police or by the parents of kids who had been brutalized or killed. It was another reminder to me of how rarely I have to preside over the funeral of a child or teenager and how often African-American clergymen who live nearby have to do so.

On Shabbat morning, May 2, we had a good crowd in shul, including many members who don’t typically come but who are proud of their urban congregation and wished to show solidarity. I spoke about showing up, about how important it was not just to be for and of our neighborhood, but to be fully present in it. After the sermon we walked outside and davened on the steps of the shul. It was a sunny, breezy day and it was good to sing and pray, wrapped in our talleisim, less than a mile from Mondawmin Mall where the rioting had first broken out. Somebody walking by said “It’s a beautiful thing. We need all the music we can get out here.”

Suggested Reading

The First Maggid—How Memory Made the Jews

3,500 years ago, Israelite parents explained wonders to their children and created the very first Maggid story.

Haredim and COVID-19: Tenants or Landlords?

Between rabbinic rulings and public policy: a response from Daniel Goldman and Yossi Shain and a rejoinder from Yehoshua Pfeffer.

Weird Big Brother

Jacob Frank and his bizarre religious movement still casts a strange spell over. Is Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk’s newly translated novel the War and Peace of Jewish-Polish heresy?

Torah U’Madda

Only 3 percent of American Jews are Modern Orthodox, but that number belies the movement's diversity.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In