No Joke

Nemesis is unlike anything that Philip Roth has ever written. Humor is an absence and God a presence. American history, which normally captivates Roth when writing about Newark, the central setting in Nemesis, goes unexplored. The historical rhythms are there, but they are grim and inscrutable, hardly the melody of post-war progress and plenty that fascinated Roth in his literary youth. The splendid self-making documented in such later novels as American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain has given way to “the force of circumstance,” to the unjust, unknowable dictates of fate. The novel’s protagonist, Bucky Cantor, does not pursue a new self. Only reluctantly does he pursue self-gratification; he is neo-Victorian in his attachment to duty and very much the aspiring Jewish hero. For all of this he is punished by his heartless God the way a pleasure-seeking rake might be punished in a morality play.

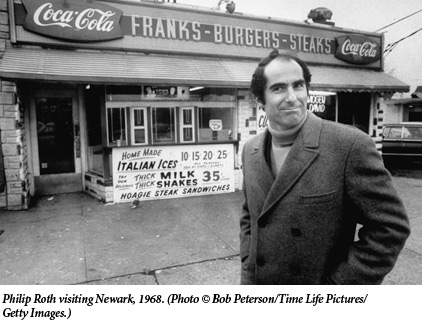

Roth has not returned to the place of his famous debut Goodbye, Columbus because, as a novelist, he has never really left Newark, New Jersey. One section of American Pastoral is titled “Paradise Remembered” and another “Paradise Lost.” The paradise in question is Newark before 1967, where immigrants made their homes and survived the Great Depression. In the 1940s, their children struggled to win a just war, and then devoted themselves to the wholesome labor of success. In Nemesis, the streets are the familiar Newark streets; Weequahic the familiar Newark neighborhood. Even the patriotic wartime ambiance is familiar from the opening pages of American Pastoral. Yet the city itself is strangely terrifying.

Nor is the Jewish-American world of Nemesis the same world that Roth has previously chronicled. The novels after Goodbye, Columbus can be read as meditations on Jewish-American freedom. Never before in the history of the Diaspora had Jews been as free as these post-war American citizens—the Patimkins, the Portnoys, the Zuckermans. The Zuckerman novels, from The Ghost Writer through The Human Stain, portray Newark progeny breaking free from Newark, breaking free, really, from the limiting dictates of Jewish history. Mickey Sabbath, in Sabbath’s Theater, takes this freedom to its logical extreme. As a youth, he leaves Newark for the open seas, rather like Melville’s Ishmael; but he is an Ishmael without tact or piety, tasting every pleasure, risking every joke, and pursuing every infidelity.

The Plot Against America, a counterfactual novel of an America approaching fascism, was Roth’s first step in the direction of Jewish fear, back in the direction of “Europe.” Nemesis is even less conciliatory, and its fears are more vividly pictured. Roth describes a mother worrying about her children’s safety, “a small, dark woman laden with fear, her face contorted with emotion.” At the height of a polio epidemic, a radical quarantine is discussed for Newark, with rumors that the Weequahic Jews will be restricted to a ghetto.

In Nemesis, Bucky Cantor is an American with the mentality and physique of a mid-century Zionist. His grandfather had endured anti-Semitism in Newark: “the violent aggression against Jews that was commonplace in the city during his boyhood did much to form his view of life and his grandson’s in turn.” Bucky is a strong, athletic man whose dream is to teach physical education at Newark’s Weequahic High School. He wants to teach the students there “what his grandfather had taught him: toughness and determination, to be physically brave and physically fit and never to allow themselves to be pushed around or, just because they knew how to use their brains, to be defamed as Jewish weaklings or sissies.” This dream compensates for what Bucky cannot do on Europe’s battlefields, due to his poor eyesight.

Exiled from World War II, Bucky finds himself imperiled in peaceful America. Occasional air-raid sirens merge with the more frequent “sound of the ambulance sirens crisscrossing Newark in the night.” The polio virus terrifies Newark, and it devastates Bucky. First it murders the children at the local playground for which he is responsible, then it strikes at a summer camp where he is working. Finally, Bucky himself contracts the virus, suggesting that he has been its carrier all along. Polio disfigures Bucky’s body and so inundates him with guilt that he separates from his fiancée, growing into an embittered, isolated adulthood. In the verdict of the novel’s narrator—a Newark boy who contracted polio in 1944—Bucky is “one of those people taken to pieces by his times.”

Roth’s previous four novels—The Dying Animal, Everyman, Indignation, and The Humbling—are each novella-length essays on mortality, and, though here the protagonist does not die, so is Nemesis. As in these other late works, the prose of Nemesis is sparse, but it also contains moments of great lyric beauty. When Bucky, his mind filled with death, goes from overheated Newark to a summer camp in the Poconos, he is overwhelmed with joy. It is the basic joy of being outdoors, of being young, and of being engaged to a beautiful woman. For the first time he feels “that commingling of warmth and coolness that is a July mountain morning.” Amid nature’s bounty, he lives “the rapturous intoxication of renewal.”

The conclusion of the novel, set in 1971, outlines Bucky’s barren spiritual life. Beneath the Maccabean athlete and the boyish nickname is a man who resembles Kafka’s K., disempowered and despairing, and, as with K., part of Bucky’s predicament lies within him. Even when healthy, Bucky “was sure he would come down with polio and lose everything.” Guilty of nothing, he is inclined “to convert tragedy into guilt.” The burden of suffering without crime leaves him a “maniac of the why.” In sum, “such a person is condemned.”

Medically speaking, the polio epidemic begins in obscurity. As far as Nemesis is concerned, however, the epidemic begins when a carload of Italian-Americans visit a playground in a Jewish neighborhood and deliberately spit on the ground, intending to spread the virus. The ironic parallels between polio and the war, between good fortune and bad luck, between Europe and America develop apace. Bucky’s bad eyesight saves him from the war but leaves him vulnerable to infection in Newark. He cannot fathom the contingencies of fate, why some children died “because they’d spent the summer in Newark” and why others “were flourishing because they were spending the summer in Indian Hill,” a bucolic summer camp. When one of his friends dies in the war, he cannot grasp this either. Gradually, the polio epidemic and the war merge, provoking Bucky into a theological rage.

Bucky’s abiding relationship to God has no precedent in Roth’s fiction. Usually Roth’s heroes swim in a sea of atheism; they may be robustly Jewish, obsessed with Jewish questions, trailed by Jewish families, mired in a Jewish milieu, or sensitive to the thrill of being Jewish, but Neil Klugman, David Kepesh, and Coleman Silk are not obsessed with God. They know that he is dead and live securely within that knowledge. Bucky is different, though his theology consists of “hating God.” He hates God for a cruelty that includes the “cold-blooded murder of children.”

Nemesis is a sternly serious book with only a few moments of humor. Roth lingers over an Indian-themed summer camp, where East Coast Jewish kids cover themselves in feathers, invoke tribal spirits, and chant around the campfire. The boys “carried deer antlers before them, made of crooked tree limbs bound together . . . [and] set out by the light of the fire to hunt Mishi-Mokwa, the Big Bear. Mishi-Mokwa was impersonated by the largest boy in camp, Jerome Hochberger . . . wrapped in somebody’s mother’s old fur coat that he’d pulled up over his head.” Even here, the humor is subdued. It is as if Roth lets his protagonist’s punishing sobriety set the tone for Nemesis:

He was largely a humorless person, articulate enough but with barely a trace of wit, who never in his life had spoken satirically or with irony, who rarely cracked a joke or spoke in jest—someone instead haunted by an exacerbated sense of duty but endowed with little force of mind, and for that he had paid a high price in assigning the gravest meaning to his story, one that, intensifying over time, perniciously magnified his misfortune.

The unsmiling author of Nemesis, one of America’s greatest comic writers, cannot have given up on humor. In the 1960s, after publishing Goodbye, Columbus at the age of 26 and introducing his readers to the comedy of Jewish suburbia, Roth wrote two sternly serious (and not very well received) novels, Letting Go and When She Was Good. The work that gave Roth his unshakeable reputation as a “sit-down comedian”—a phrase Roth has used to describe Kafka—was Portnoy’s Complaint, to which Nemesis is an unlikely companion volume.

Like Bucky, Alexander Portnoy antagonizes himself. His suffering is his guilt, his guilt his suffering. From suffering, as from guilt, there is no relief and no exit for either of these two Newark sons. Alexander Portnoy’s suffering is also ridiculous, and it is here that Portnoy’s Complaint and Nemesis diverge. Portnoy is successful, intelligent, and handsome. He is at ease in the American paradise, just as Americans are at ease with him, and this makes him miserable. “I am the son in the Jewish joke,” he famously observes to his analyst, “only it ain’t no joke!” Bucky does not tolerate or inhabit jokes; he is a tragedy uncomplicated by laughter.

Suggested Reading

The Nation of Israel?

The case for an Israeli—not Jewish—republic.

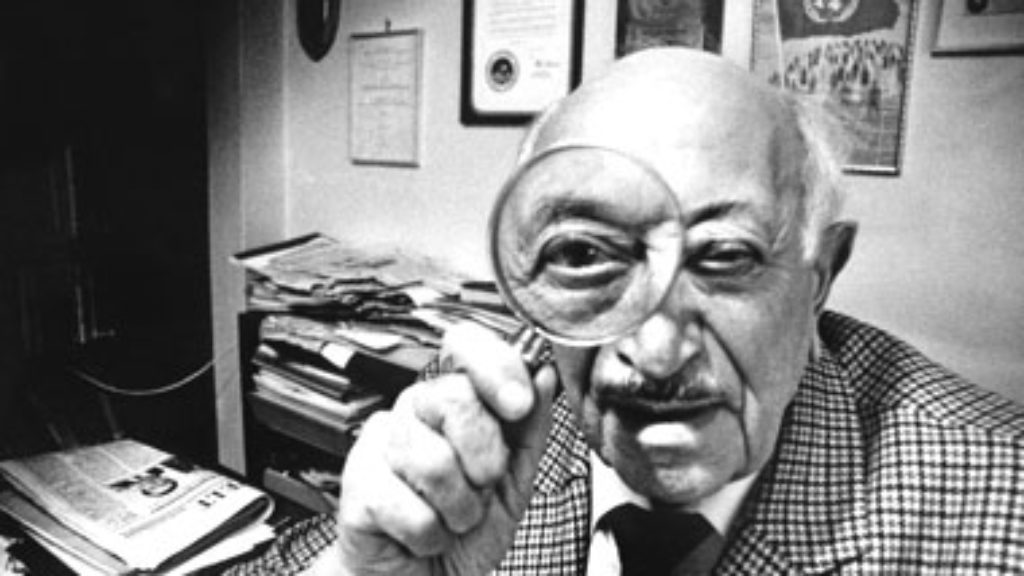

Simon Wiesenthal and the Ethics of History

Was Simon Wiesenthal an intrepid hunter of mass murderers? Or was he in fact more of a charlatan than a hero? Tom Segev's new biography of the most successful—and controversial—Nazi-hunter raises more questions than it cares to answer.

Mystical Teachings Do Not Erase Sorrow

In Yehoshua November’s new collection, however, it turns out that the difficulties of being a Jewish poet do not primarily flow from being either Jewish or a poet but from the underlying difficulties of life itself.

Bind Them as a Sign: A Photo Essay

A Hasidic-owned, bicycle-powered tefillin factory in Krakow, Poland.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In