Tradition, Creativity, and Cognitive Dissonance

Just over a year ago in these pages, I wrote a requiem for Conservative Judaism. In the aftermath of the controversy stirred up by that essay, I have continued to think about what went wrong with the movement. At the very same time, I have also been writing a short history of Israel and about the ways in which Zionist ideas did—and did not—come to fruition in the Jewish state. Perhaps inevitably, the two projects have begun to inform one another. Conservative Judaism at its peak reminds me, in its astonishing wealth of intellectual talent, of the formative era of the Zionist enterprise. There was an explosion of Jewish thought and scholarship at the movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary in the middle of the 20th century that, at least in its brilliance, bears comparison to the renaissance of Jewish creativity among European Zionist thinkers at the century’s outset.

On one level, the following reflections are personal. I grew up in a family that produced several leaders of the Conservative movement (including my grandfather, Rabbi Robert Gordis, my father’s brother, Rabbi David Gordis, and my mother’s brother, Rabbi Gerson Cohen). And for almost two decades, I have lived in the state first envisaged, and argued over, by the turn-of-the-century Zionists.

Yet I have also had occasion to think about Conservative Judaism and Zionism in ways that are not merely personal. Why, I have found myself wondering, did one project largely succeed and the other mostly fail? For all its many shortcomings and rather uncertain future, the State of Israel is in large measure what its founders had hoped it would be—Jewish, democratic, able to defend itself, and a center of Jewish cultural life. Conservative Judaism, however, for all its many accomplishments, did not achieve the fundamental goal the movement set out for itself—the creation of a modern, yet halakhically committed laity in which Shabbat, kashrut, daily prayer, and serious learning would be the lynchpins of a renewed American Jewish life. So what might the history of those two movements tell us about our own intellectual initiatives and prospects today?

Obviously, there were factors—historical, sociological, geopolitical—beyond the control of any intellectual tradition or movement that were involved in the (relative) success of the Zionist project and the (relative) failure of Conservative Judaism. Their respective fates may even have turned, to some extent, on matters of sheer historical contingency (or, if you prefer, divine providence). Nonetheless, both movements were moved by thinkers and ideas, and it is worth thinking about them as such.

In the 1950s, The Jewish Theological Seminary, the intellectual headquarters of the Conservative movement, was a small academic institution that boasted an extraordinary list of luminaries. It included, among others, Alexander Marx (historian and, as it happens, S. Y. Agnon’s brother-in-law), Louis Finkelstein (historian and voice of American Jews to the wider American community for some time), Saul Lieberman (the leading talmudic researcher of his era), H. L. Ginsberg (the revolutionary Bible scholar), Abraham Joshua Heschel (the influential poet-philosopher and social activist), Robert Gordis (Bible scholar and ideologue of the Conservative movement), Nachum Sarna (Bible scholar), David Weiss Halivni (then an up-and-coming talmudist, today perhaps the greatest Talmud scholar of our era), and Mordecai Kaplan (the theologian and ultimately father of Reconstructionist Judaism).

Most of these men were educated in both the Jewish intellectual tradition and, subsequently, modern universities. Heschel, for example, was descended from great Hasidic dynasties, on one side from the Maggid of Mezheritch and on the other from Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev. Though he received a classic yeshiva education, he later earned a doctorate at the University of Berlin and pursued rabbinic ordination at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums. Heschel’s subsequent work—largely a series of poetic evocations of the phenomenology of traditional Judaism—was an attempt to make engagement with God possible for pragmatic modern Americans. His work, though, is clearly informed not only by a passionate love for Jewish learning and ritual, but by the philosophical richness of European thought and scholarship and his American intellectual peers, both Christian and Jewish.

On the surface, it might appear that Heschel’s project and the work of Saul Lieberman had little in common. Heschel was, in his distinctive way, both a Hasid and a poet; Lieberman was a pure talmudist, a classic Litvak. Heschel sought to speak to a wide lay audience, while Lieberman was interested only in the academy. Heschel became famous outside of Jewish and academic circles through his bold activism; Lieberman confined himself to the ivory tower. Heschel’s spiritual vision inspired two generations of JTS students, while Lieberman communicated a disdain for the vast majority of the students JTS obliged him to teach.

Yet as different as the two men clearly were, they actually were part of the same large religious project. Lieberman, a product of the European yeshiva of Slobodka who never really left Orthodoxy, wrote only two books in English. The almost identically titled Greek in Jewish Palestine and Hellenism in Jewish Palestine both trace the influence of Hellenistic culture on Jewish Palestine at the beginning of the rabbinic period. He was, in a broad but relevant sense, like Heschel, a product of two worlds whose research and writing focused on the collision of two somewhat analogous worlds two millennia earlier. By yoking his personal, old-world piety to the intellectual rigor of the academy, Lieberman modeled the claim that the two could coexist. And that was precisely what Heschel was claiming too.

The same is true of David Weiss Halivni, Lieberman’s most important disciple. In addition to all of his source-critical analysis of the Talmud, Halivni has been consumed by the project of making traditional Judaism intellectually palatable for those who are troubled by historical criticism. Two of his books, Peshat and Derash and Revelation Restored, seek to enable biblical criticism to coexist with traditional Jewish theology and belief.

The world of JTS in that period was, however, not only a hub for exceedingly talented men (there were then no women among JTS’s leading lights) who were straddling two seemingly incompatible Jewish worlds. It was also a place of intense debate and disagreement. Lieberman, after all, shared JTS with Mordecai Kaplan. Kaplan’s life, too, spanned two worlds. Born in Lithuania to an Orthodox rabbi father, he moved to the United States as a young boy, where he attended the Etz Chayim Yeshiva in Manhattan, studied at JTS, and ultimately earned a doctorate from Columbia. Kaplan, who ended up rejecting both the idea of a transcendent God and Jewish chosenness, was the object of Lieberman’s scorn (and Heschel’s dismay).

Even more moderate Conservative ideologues like my grandfather Robert Gordis thought Kaplan had gone too far. JTS was home to many people who embodied the clash of civilizations, but it was also a hotbed of significant disagreements. What they all had in common, despite their great differences, was a sense of urgency. Each of them sought to forge an intellectual and religious path that could bridge the chasm between the worlds in which they had been raised and the American community to which they were devoted. Jewish thought had to be couched in language that would appeal to a generation of university-educated Jews. Jewish practice had to be reshaped so it did not remind them of their grandparents (or at least not too much). Jewish particularism had to make space for a post-war American world that was proving hospitable to Jews in an unprecedented and distinctly non-European way. The challenge of Conservative Judaism was to refashion Jewish thought, study, and practice so that what was most important and vital in Judaism could survive and even thrive in a bright new America.

For Lieberman and Halivni, the pursuit was academic and the bridge was between the world of the yeshiva and the methodologies of the American academy. For Finkelstein, the chancellor of JTS throughout this period, the goal was to accommodate the sensibilities of classic, particularistic Judaism to the sense of universalism increasingly at the heart of American life. For Kaplan, Heschel, and others, the aim was to create new ways of thinking about theology, practice, and the relationship between Jews and Christians—all while preserving the centrality of and a reverence for the texts and rituals key to classic Jewish life. That aspiration is reflected in titles such as Judaism for the Modern Age, A Faith for Moderns, Judaism in a Christian World, and Faith and Reason (all by Gordis).

That the Zionist revolution was a profoundly literary one is, even if insufficiently appreciated, widely recognized. David Ben-Gurion, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, Yosef Brenner, Micha Josef Berdyczewski, Ahad Ha-Am, Chaim Nachman Bialik, and innumerable others all wrote both copiously and compellingly. Herzl’s tiny book, The Jewish State¸ ignited an international political movement in a matter of weeks. Bialik’s poem “In the City of Slaughter” indicted Jewish religious tradition and helped shaped Zionist secularism for decades. Ben-Yehuda’s vision revived a language. Jabotinsky and Herzl, though serious political thinkers, both wrote fiction, as well.

Zionist thinking around the turn of the century was even more extraordinary than that list suggests. The roster of Zionist thinkers who were born in the half-century between 1842 and 1892 includes not only the seven figures mentioned above, but also Max Nordau, A. D. Gordon, Abraham Isaac Kook, Chaim Weizmann, Beryl Katznelson, and numerous others. Though space precludes an examination of each of the people on our list, let alone the dozen or two others one might add, a few brief vignettes will suggest the difficult intellectual circumstances under which, perhaps paradoxically, they flourished.

Ahad Ha-Am (born Asher Ginsberg) was raised in a Hasidic family and educated in a cheder. But he was also drawn to the world of the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah), as well as to Russian and European literature. Though he gradually moved away from traditional Jewish life, he never left it entirely. In an uncharacteristically revealing article, “Ketavim Balim” (A Tattered Manuscript), he revealed the tension that this meeting of two worlds created for him, when he wrote in 1888:

During those long winter evenings, at times when I’m sitting in the company of enlightened men and women, sitting at a table with treif [non-kosher] food and cards, and my heart is glad and my face bright, suddenly then—I don’t know how this happens—suddenly before me is a very old table with broken legs, full of tattered [sacred] books (sefarim balim), torn and dusty books of genuine value, and I’m sitting alone in their midst, reading them by the light of a dim candle, opening up one and closing another, not even bothering to look at their tiny print . . . and the entire world is like the Garden of Eden.

Bialik, who would become Ahad Ha-Am’s most important disciple, traveled a similar path. He was raised in a traditional home, and studied at the prestigious yeshiva in Volozhin, before leaving for Odessa and the intellectual riches and challenges of the Haskalah. For Bialik, too, the meeting of two radically different worlds was a source of (undoubtedly creative) tension. In his classic poem, “Ha-Matmid” (The Diligent Talmud Student), he describes yeshivot such as Volozhin:

There are abandoned corners of our Exile,

Remote, forgotten cities of Dispersion,

Where still in secret burns our ancient light,

Where God has saved a remnant from disaster.

Which is not to say that he wants to return, or even thinks that this is a corner of the world to which a modern could return:

It is a Matmid in his prison-house,

A prisoner, self-guarded, self-condemned,

Self-sacrificed to the study of the Law.

Nonetheless, Bialik cannot bring himself to give up entirely on the Matmid:

How rich would be the blessing if one beam

Of living sunlight could break through to you;

How great the harvest to be reaped in joy,

If once the wind of life should pass through

you . . .

If the Haskalah provided the beam of light and Zionism the wind of life, the prospective harvest could be reaped only through a new approach to tradition and classic texts.

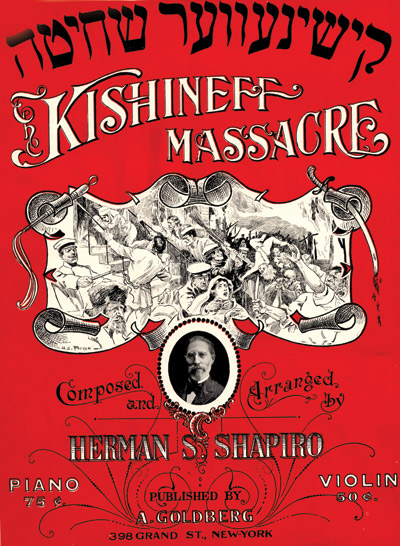

Together with this now familiar modernist crisis of tradition came a distinctively Jewish sense of historical urgency. It was clear to most of those early Zionist thinkers that Jewish life in Russia and Europe was on the verge of catastrophe. Herzl convened the First Zionist Congress in 1897, of course, but if there were any doubt as to the fragility of the Jewish condition in Europe, the Kishinev pogrom of 1903 erased it. The barbarity of Kishinev as it was described in press reports and ultimately in Bialik’s great, angry poem was, at the time, virtually unimaginable.

For many of those Zionist thinkers, the brutality at the onset the 20th century (which would pale in the face of the horrors of the middle of the century) created the urgency of finding a solution to the “Jewish problem” in Europe. At the Sixth Zionist Congress, in 1903, Herzl invoked Kishinev, insisting that it was not an event or a place, but rather a condition. “Kishinev exists wherever Jews undergo bodily or spiritual torture, wherever their self-respect is injured and their property despoiled because they are Jews. Let us save those who can still be saved!” he insisted. Even Ahad Ha-Am, who was focused on the cultural dimension of Jewish life and therefore dismissive of Herzl’s purely political solution in Palestine (or anywhere else), understood that Kishinev mandated a profound change. “It is a disgrace for five million human souls to . . . stretch their necks to slaughter and cry for help, without as much as attempting to defend their own property, honor and lives.”

Ahad Ha-Am’s reaction to Kishinev is instructive. For the father of the idea of Zion as a spiritual center to have recalibrated his stance in reaction to the atrocities was characteristic of those early Zionist thinkers. Few of them were rigid in their thinking. They were part of a conversation in which intellectual creativity went hand in hand with continual reassessment in the face of the urgency of the problem they faced. Sometimes Jabotinsky sounded like a political liberal, at other times more reactionary. Berdyczewski vacillated between a rejection of Judaism’s exilic culture and a recognition—often as a result of the influence of Ahad Ha-Am—that without a profound attachment to the past, Judaism would not survive.

Consistency, in short, was not the goal of the early Zionists. Creativity was. And, of course, the project proved successful. The richness of Jewish traditional life and the identity it forged, the attraction of the Haskalah and the productive intellectual tension it unleashed, together with the increasing sense of a desperate Jewish urgency, led to a burst of Jewish creativity that ultimately resulted in the creation of the state of Israel.

Thus, in the Zionist movement, three factors seem to have converged. First, most (though not all) of the men listed above were raised in traditional homes and received substantial Jewish educations. They were comfortable in the classic tradition, and the narrative of Jewish history was (to borrow Charles Taylor’s term) the “inescapable horizon” against which they measured and plotted their lives. Homeland, diaspora, exile, redemption—all key to the biblical, rabbinical, and post-rabbinic super-narratives of Jewish life—were notions with which they were deeply imbued. For people raised that way, questions of personal paths and goals were invariably plotted on a map of Jewish past, present, and future.

Second, while they possessed an intimate understanding of the richness of Jewish tradition and the chorus of voices emerging from its texts, most of these thinkers and writers were also deeply affected by the broader intellectual currents of their times. Their lives were lived at the intersection—or collision point—of Jewish tradition and European modernism. The cognitive dissonance and the new set of problems and possibilities created by being dedicated to both seem to have fueled their thinking and writing. And, finally, there was the palpable political urgency they all felt, to which Zion was, in some sense, the solution.

Why was the intellectual movement of Conservative Judaism ultimately not as successful as that of the Zionists? After all, Heschel, Lieberman— how they would both hate that conjunction!—and company were gripped by the conflicts between tradition and modernity, and, if anything, with the possible exceptions of Ahad Ha-Am and Rav Kook, they were even more learned than anyone in

that first generation of Zionist thinkers. Part of the answer, of course, lies in the different senses of existential urgency each project embodied. Conservative Judaism was a valiant attempt to create a distinctly American Judaism in an era in which Jews were seeking new language and demanding new answers, but the nobility of that project was no match for the utter urgency of the Zionist project. Prior to the Shoah, many Zionist leaders foresaw a coming cataclysm and desperately hoped to create a home for the Jewish people that might serve as a safe harbor. After Europe liquidated most of its Jews, the problem of how to find a home for the thousands who, though not dead, were utterly homeless confronted Zionism with an urgency that American Judaism never experienced.

Just as importantly, preserving a fruitful cognitive dissonance proved far more difficult for Conservative Judaism than it did for Zionism. Israel inherited—and could not avoid—the radical disagreements that had always made Zionism so alive. The early battles among Zionist thinkers lingered on. Bialik and others had advocated the creation of a secularized “new Jew,” an ideal which religious Zionists emphatically rejected. Herzlian Zionists believed that the Arabs would welcome the Jews with open arms; Ahad Ha-Am was skeptical; Jabotinsky warned of perpetual conflict. In some ways, Israel achieved independence too early; it gained sovereignty before any of these—and many other—debates would be resolved. Israel swept together religious Jews who now had to share a society with secular Jews who rejected everything they stood for and secular Jews who saw in their religious counterparts the very reason for the passivity that had led to the Holocaust. Israel’s Ashkenazi elites knew nothing about and cared not at all for the Mizrachim, while those Jews from North Africa could not abide the secular Western European Jews who seemed the very antithesis of what sustaining the Jewish people and its traditions was all about.

Such circumstances had no counterpart in American Jewish life. Moreover, in its desire to accommodate its laypeople and its belief that ideological consistency was an intellectual badge of honor, Conservative Judaism time and again tailored its reading of Jewish law to the practices and inclinations of its folk, to whom it wished to transmit a coherent Jewish vision devoid of the raucousness that characterized the Zionist debate. In doing so, however, it eradicated the cognitive dissonance that had been at the heart of its very own Jewish creativity.

It would be intellectually dishonest, however, to make Conservative Judaism a sacrificial lamb for wider American trends of which it is just one manifestation or to let Israel off the hook too easily. Zionism is hardly the rich conversation that it once was. One would be hard pressed to find rich visions of Jewish life in contemporary Israel as obsessively and intelligently discussed as they were in the period so magnificently captured in Arthur Herztberg’s classic anthology The Zionist Idea. To be sure, statehood has complicated what was earlier a mostly theoretical conversation, but if anything, the issues that Jewish sovereignty has raised should have produced more great thinking, not less. Similarly, in America, it is not only Conservative Judaism that is a shadow of its former self. The American Jewish world that had, at the very same moment, not only Heschel, Kaplan, and Lieberman but also Eugene Borowitz and Joseph B. Soloveitchik, has no parallel today. Is there anything we can do to revive the creativity of both the Zionist and the American Jewish worlds?

Pondering this challenge, I stumbled across Randall Collins’ magisterial The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. (One must either stumble or leap: It runs to 1,098 pages.) Collins’ book is full of little diagrams showing how deeply repercussive ideas and movements sprang from small clusters or networks of thinkers from neo-Confucian China to the German Idealists. How are such small groups of intellectuals successful? Collins writes:

I suggest three processes, overlapping but analytically distinct . . . One is the passing of cultural capital, of ideas and the sense of what to do with them; another is the transfer of emotional energy . . . [and] the third involves the structural sense of intellectual possibilities, especially rivalrous ones.

These factors, presented by Collins in dry social-scientific prose, overlap to some extent with my more impressionistic sense of the factors leading, in part, to the Zionist success, but they also suggest something of the evanescence of that brilliant generation or so of Conservative Jewish thinkers.

Although the JTS faculty was one of the most glittering collections of Jewish intellect ever gathered under one roof, it was, in the end, less than the sum of its professors. Rivals they certainly were, but there was little genuine exchange of ideas. Lieberman, Heschel, and Kaplan spoke more at each other (or even about each other) than with each other. There was little dialogue, and the “transfer of emotional energy,” to use Collins’ phrase, was largely negative. They were argumentative, but they were not, in another of Collins’ useful formulations, an “argumentative community.”

The same is true of the cacophony of visions in Israel now. Nowhere in the contemporary Jewish scene—either in America or in Israel—do we find the “argumentative community” of which Collins speaks. Nowhere do we find the desperate, urgent, learned, cognitively dissonant intellectual world of turn-of-the-century Zionist discourse, or even that of mid-century Conservative Judaism.

In the United States, as the Pew study has made clear, the contemporary case for Judaism is falling on far too many deaf ears. We desperately need to recreate a world of Soloveitchiks, Heschels, Kaplans, and Borowitzes. Yet Israel is in no less urgent need of an intellectual renewal. The Arab-Israeli conflict is almost certainly unsolvable. The threat from Iran, Israel’s most ideologically driven enemy, is now more palpable than ever. Many Israelis ask themselves why the entire Zionist project matters, and with peace utterly impossible and existential danger ever present, increasing numbers will wonder whether the Jewish state is the place in which they ought to raise their children. And the divide between American and Israeli Jews is now a gaping chasm.

Thus far, however, on all these fronts, shrill argument has replaced productive intellectual engagement. Too few Jews on either side of the ocean have inherited the Jewish cultural capital necessary to understand how Jews in the past wrestled with and responded to the challenges of their day. Too few Jews have the access to Jewish texts that would enable them to engage in authentic Jewish discourse. And too few Jews live their lives in the dissonant space at the intersection of traditions where creativity happens. The number of Jews worried to their core about the condition of the Jews—and willing to acknowledge that they have no ready solution—is very small indeed.

We know the basic ingredients of Jewish intellectual leadership: genuine Jewish literacy; a readiness to grapple with intellectual dissonance and a willingness to see “argumentative community” not as a problem, but as an ideal; and focused awareness on the urgent challenges that face us. What we do not know is whether the Jewish communities of America and Israel have it in them to recreate such leaders. For the sake of our future, we must hope that they do.

Suggested Reading

Our Master, May He Live

Rashi's commentary on the Chumash isn't just about textual puzzles, it's about God's love for the Jewish people. So argues Avraham Grossman in a new biography.

100 Years of Solicitude: Commemorating Balfour

The controversies over how (and whether) Great Britain should celebrate the recent centenary of the Balfour Declaration were revealing. Anglo-Israel relations have rarely been uncomplicated, but they could soon be much worse.

Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love

The late Michael Wyschogrod may have been the boldest Jewish theologian of the 20th century.

The Many Dybbuks of Romain Gary

Romain Gary—a Lithuanian Jew who regarded himself a Frenchman par excellence—emerges in a recent memoir as a master of self-invention and (just as immoderate) verbal invention, a chameleon of pseudonyms, a man of irreconcilable contradictions, divided against himself.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In