Islamic Jihad, Zionism, and Espionage in the Great War

Living—and writing—history in Israel has a peculiarly urgent edge. One has a painful, yet vitalizing, sense of the fragility of the social order. In times of war, this is all the more true, and it was never truer than in World War I, whose conduct and aftermath literally created the modern Middle East and its discontents. That is hardly news, and yet a closer reading of the war years in Ottoman-era Palestine yields a seemingly endless stream of unexpected revelations.

Why, after so many years, should there be such surprises? Perhaps it is because the focus of historical attention has tended to be on the unprecedented mass killings in Europe, especially on the Western Front. Perhaps too, because Germany was the loser, its role in stirring the Middle Eastern pot has been relatively understudied until recently. Moreover, given the 1917 Balfour Declaration and the victory of the imperial Allied powers, events in the already tottering Ottoman Empire have seemed less relevant in understanding later developments. Those acquainted with Zionist history will of course know that Herzl approached the sultan with his plans, and that Ben-Gurion studied law in Constantinople in order to better cope with the Ottoman rulers in Palestine. Still, for most non-specialists, the Ottoman chapter retains a certain vagueness.

And yet, it is upon this stage that a literally incredible, multi-stranded story of war and intrigue, cross-cutting imperialist machinations, incitements to jihad, and Zionist politicking unfolded. As some of the most fascinating histories and biographies written over the past few years reveal, we are confronted with an outlandish cast of personalities: explorers, orientalist adventurers (Jewish and Gentile), archaeologists, and spies—sometimes combined in the same person. Moreover one finds many of them surprisingly interconnected, even entangled, with one another, and not always pleasantly.

Take for instance Baron Max von Oppenheim, a now virtually forgotten but then notorious figure in German-Turkish politics, who remained active in Middle Eastern affairs through the Third Reich. A descendant of a prominent Jewish banking family, the son of a Catholic mother and a Jewish father who had converted at the time of his marriage, he was fascinated from an early age by the romance of the Orient. A well-informed ethnologist of Bedouin culture, amateur explorer, and archaeologist, he was the discoverer of the fabulous findings at Tel Halaf in northern Syria (the site is now in a Kurdish stronghold). During his periods in Cairo and elsewhere in the Middle East, Oppenheim often dressed in Arab garb, living lavishly and keeping a harem of young concubine slaves.

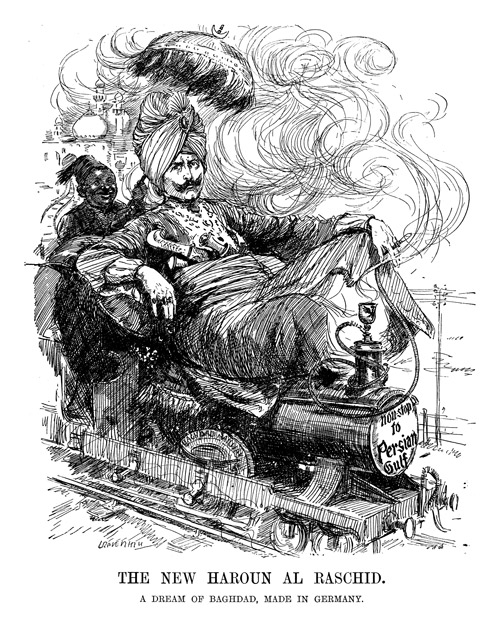

But Oppenheim’s involvement in the Middle East was not limited to orientalist curiosity and (apparently realized) sexual fantasies. Passionately involved in the intricacies of Arab politics, he filed hundreds of reports with the German Foreign Office between 1896 and 1909 on Ottoman politics and Germany’s possible role in them. Few paid attention to Oppenheim, but given the dangerously erratic kaiser’s pre-war proclamations in Constantinople and elsewhere about the greatness of Islam, and the kaiser’s intention to be the sultan’s great protector against all European imperialist depredations, Oppenheim’s strategic message was suddenly welcome. As Sean McMeekin showed in his brilliant The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany’s Bid for World Power (reviewed in these pages by Jordan Chandler Hirsch, Summer 2011), Germany’s leaders saw in Islam the secret weapon that would decide the war in their favor. By encouraging uprisings of colonized Muslim subjects in India, Egypt, North Africa, and the Caucasus, Germany could divert the energies and resources of Britain, France, and Russia respectively, thus giving German and Ottoman forces the upper hand.

Oppenheim’s 1914 “Memorandum Concerning the Fomenting of Revolutions in the Islamic Territories of Our Enemies” was, according to McMeekin, nothing less than a “blueprint for a global jihad engulfing hundreds of millions of people,” covering everything from propaganda, the burning of oil wells, and the full-blown invasion of British Egypt and India, to a ruthless writing off of minorities deemed not to serve German interests. The sultan-caliph was to head this global jihad, thus mobilizing the entire Islamic world to fight alongside the Central Powers “in the greatest war that has ever erupted on this earth.”

Toward that end, Oppenheim created propaganda centers, recruited agents to stir up religious passions, raised considerable amounts of bribe money, met with and armed potential tribal allies, and had a guiding hand in the ultimately failed attempt to create the Baghdad-Berlin express, the train which was to have united East and West and laid the infrastructure for Germany’s Weltpolitik. No wonder that the British called him “the kaiser’s spy.”

The combination of pan-Germanism and anti-imperialist Islam under the Ottoman Turks initiated an imperialist race. In response, the British subsidized Wahhabism and the sherifate of Mecca to take on the role of the caliphate. Today’s revival of ambitions for a caliphate and the slaughtering of “infidels” has its partial origins in the stratagems of the competing, conniving European powers. “The killing of infidels who rule over the Islamic lands,” Oppenheim declared in a chilling pamphlet, “has become a sacred duty, whether it be secretly or openly, as the great Koran declares in its words: Take them and kill them whenever you come across them . . .”

To be sure, there were always practical objections to Oppenheim’s plan: Most Bedouins lacked the kind of ideological commitment and motivation he expected of them. Moreover, the strategy was based upon an illusory notion of Islamic brotherhood that discounted Sunni-Shia tensions, not to speak of the hatred of Arabs for the ruling Turks. And then there were the inner contradictions of Oppenheim’s plan: A global jihad entailed death to infidels everywhere, but, of course, Oppenheim’s jihadi vision excluded Turkey’s war allies, the Germans, Austrians, and Hungarians. Indeed, as the tides of war shifted, many of the enlisted Muslims did indeed turn violently against their purported German partners. In the end, as one of Oppenheim’s central agents put it, the whole thing ultimately turned out to be “a farce.”

Although Oppenheim is a central character in McMeekin’s volume and Scott Anderson’s thrilling Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East (reviewed in these pages by Hillel Halkin, Winter 2014), his “Jewish problem” has recently been highlighted in Lionel Gossman’s The Passion of Max von Oppenheim: Archaeology and Intrigue in the Middle East from Wilhelm II to Hitler. Wealthy, baptized, and ennobled, Baron Oppenheim did not consider himself a Jew, but many others certainly did. His position with the German Foreign Office and Civil Service was constantly impeded by his Jewish family background. In 1887, his application to the German diplomatic service was refused. In a private letter, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Herbert von Bismarck (son of Otto) bluntly laid out the real reasons for the rejection:

I am against it, in the first place because Jews, even when they are gifted, always become tactless and pushy as soon as they get into positions of privilege. Then there is the name. It is far too widely known as Semitic and provokes laughter and mockery. In addition, the other members of our diplomatic corps, the quite exceptional character of which I am constantly working to maintain, would not be happy to have a Jewboy added to their ranks just because his father had been crafty enough to make a lot of money.

Another important official of the ministry noted that Oppenheim is “a full Jew . . . and he is a member of a banker’s family. We get many applications from people in this category . . . If an exception is allowed, there is trouble.” Oppenheim must have been aware of this kind of attitude. Yet he maintained a virtually total silence on the issue. Gossman speculates that his romantic attachment to the Middle East was “not unconnected with insecurity about his own place in a society that both admitted him to its ruling elite and . . . excluded him from it on account of his part-Jewish background.”

Whatever his state of consciousness, Oppenheim survived rather well during the Third Reich. With the passage of the Nuremberg Laws he was awarded, and unhesitatingly accepted, “honorary Aryan status.” The family bank was “Aryanized,” but most Jewish Oppenheims escaped relatively unscathed. In his post-war memoir of the Third Reich, Oppenheim mildly criticized Nazi policy, but nowhere did he acknowledge the extent of crimes against the Jews and their suffering—or his own Jewish background. Even more startling is the fact that he again submitted his pan-Islamic jihad plan—in somewhat shortened form—to the German Foreign Office in 1940. This time it was the Muslim populations of Germany’s allies, Vichy France, and Italy who were, of course, exempted from jihad while the anti-British venom was to be maintained.

Oppenheim had plans for Palestine as well: “In Palestine, the struggle against the English and the Jews is to be taken up again as energetically as possible . . . a government should be set up under the Mufti.” The mufti, Hajj Ammin al-Husseini, he declared, was “energetic, clever, and crafty” and militant in his campaign “against Jewish infiltration.” Jerusalem could be given a special administration in which representatives of the different churches (Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox) and of the Jews would work together under the mufti. In essence, his proposed Jewish policy prefigured the early PLO position: “Only those Jews should be allowed to remain in Palestine who were there before World War I.”

According to Scott Anderson, while Chaim Weizmann was doing everything possible to support the British during World War I (and in return mobilize British support for Zionism), his sister Minna—known to friends and family as Fanny—was embroiled in a love affair with Oppenheim’s main agent of jihad in the Middle East, the seductive, soft-spoken, polyglot Curt Prüfer, who she had met in Jerusalem. Germany’s counter-intelligence chief in Syria soon enlisted Fanny to infiltrate circles in British-held Egypt and spy for Germany.

His choice was shrewd. Prüfer knew that Russian Jews despised the anti-Semitic tsarist regime and would jump at the chance to damage tsarist interests by striking against Russia’s British ally in the region. Moreover, with their Russian passports entry to Egypt was relatively easy. As a physician, Minna had access to elite British society, charmed all in sight, and provided the Germans with information of British activities until she was caught and arrested. She eventually returned to Palestine after being included in a Russian-German prisoner exchange.

Perhaps it is because she was on the opposite side of her brother, the future first president of Israel, that Minna Weizmann has been almost completely airbrushed out of Zionist history. In his autobiography, Chaim Weizmann himself barely mentions her. There are further ironies to the story. Probably unaware of Prüfer’s affair with Minna, Weizmann later met Prüfer and suggested that they both work against France, which had influenced Britain to back away from plans for the Jewish state (from then on Prüfer remained permanently on the MI5 blacklist). Neither Chaim nor Minna could have known that in 1936 Prüfer would become the personnel director of Hitler’s foreign ministry.

Of course, there was a Zionist (or anti-Zionist) angle to almost every intrigue. Astonishingly, Oppenheim’s jihadist plan was supposed to operate in tandem with what Sean McMeekin has described as “an Israelite-cum-Zionist rebellion in Russia.” The idea was that once it became clear that the global Zionist movement had the backing of Germany, Jews in the Pale of Settlement would sabotage grain supplies and deliveries, thus starving the Russian army. Russian Jews would then lead the way in toppling the Russian tsar, the greatest enemy of world Jewry. This was all based upon absurdly exaggerated ideas of international Zionist influence and power. At least at the beginning of the war, German Zionists (albeit unofficially) also adopted this dangerous conflation of war, Jews, and revolution. To be sure, no such conspiratorial Zionist rebellion ever took place, but they were playing with fire. The subsequent Nazi myth of Judeo-Bolshevism would soon take on murderous form, and, in fact, it stubbornly persists to this day in several post-communist societies. An additional irony: Britain’s decision to issue the Balfour Declaration was motivated, in part, by the fear of Germany’s support for Zionism, an exaggerated perception of the power of world Jewry, and a desire to preserve the loyalty of Russian Jews to their nation’s collapsing war effort.

(© Beit Aaronsohn-Museum Nili, Zikhron Yaakov.)

While Oppenheim and Fanny Weizmann (albeit with radically different motivations) carried out their intrigues for the Germans, there were also Jewish spies who identified with the Entente, especially the British. The NILI spy ring in Palestine was established by the brilliant botanist Aaron Aaronsohn and his sister Sarah (the acronym stands for a line in the First Book of Samuel: “Netzach Israel lo yeshaker” (roughly, “the Eternal One of Israel will not lie”). Fervent Zionists, the Aaronsohns had been convinced by the Armenian massacres that the Turks had a similar fate planned for the Jews. The future of Zionism, they were sure, lay in a British victory.

The British bureaucrats were at first almost comically reluctant to take on Aaronsohn as a spy. They were put off by what they took to be his brusque, pushy “Jewish” personality and suspected him of being a double agent, working on behalf of the Turks. In fact, he was ideally placed to provide them with critical information. Quite apart from Aaronsohn’s unrivaled knowledge of Palestinian geography, the Turkish governor of Syria (and Palestine) Djemal Pasha had given him permission to travel freely across the entire region in order to assess and combat a massive locust plague (which Aaronsohn did very effectively). His spy network ultimately supplied the British with invaluable information as to the deployments, resources, fortifications, and plans of the Turkish army. Eventually the operation was discovered (a carrier pigeon was intercepted and the NILI code decrypted), two of its leaders were arrested and executed, and Sarah Aaronsohn was so viciously tortured—she never divulged details of the organization—that she committed suicide while captive.

Let me interject a personal note here. I have lived in Israel for many years, and had, of course, vaguely heard of NILI, but I knew very little of its figures and history. This is not entirely accidental. It would be unfair to claim that, like Minna Weizmann, Aaronsohn has been entirely airbrushed out of Zionist history, but his role and importance have been somewhat sidelined. The reasons for this are fairly complex but, given the traditional mainstream socialist line, they are certainly connected in part to Aaronsohn’s capitalist sensibility and policies. He fought against the ideological tide for agricultural and industrial development based on capitalist expansion. His uncompromising personality and tempestuous relationship with Chaim Weizmann didn’t help either.

Whatever the reasons, this is unfortunate, because Aaronsohn seems to have been a kind of meteoric force of intellect and nature. Scott Anderson’s book, as well as earlier ones by Ronald Florence (Lawrence and Aaronsohn) and Patricia Goldstone (Aaronsohn’s Maps), brings him brilliantly to life. A Zionist visionary, brilliant agronomist and botanist—who on the hills of Mount Hermon discovered emmer, the wild genetic forebear to wheat—he became one of the most sought-after scientists of his day. He was also a forceful man of unusual courage, adroitness, and stubborn intelligence. This combination often provoked fear and resentment, but just as often his charm and powerful personality had a magnetic effect.

Almost everyone he met came under his sway. At a lunch in Chicago he sat next to former President Theodore Roosevelt, himself reputed to be a non-stop talker. Roosevelt listened raptly to Aaronsohn’s flowing commentary. “From now on,” Aaronsohn commented in his diary, “my reputation will be the man who had made the Colonel shut up for 101 minutes.” Felix Frankfurter described Aaronsohn as “among the most memorable persona I have encountered in life.” The feted English soldier Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen was a self-confessed anti-Semite, but after talking with Aaronsohn he became an ardent Zionist. Louis Brandeis was also (if less surprisingly) converted to Zionism by Aaronsohn and described him as “one of the most interesting, brilliant and remarkable men I have ever met.” William Bullitt, who co-authored a psychoanalytic study of Woodrow Wilson with Freud, wrote:

I believe he was greater than all the people I have ever known. He was like the giants from the old ages—like Prometheus. It is not easy to express his greatness in words. He was the quintessence of life, of life when it runs torrential, prodigal and joyous . . . I have never known anyone like him.

In May 1919 Aaronsohn was killed in a plane crash. The possibility of sabotage was repeatedly raised but never proven. General Allenby, who, unlike the colonial bureaucrats, was deeply impressed by Aaronsohn, wrote that his death “deprived me of a valued friend . . . He was mainly responsible for the formation of my Field Intelligence organization behind the Turkish lines.”

Photographs of these World War I characters—the amateur explorers, archaeologists-cum-spies, and diplomats—sooner or later show them donning Arab or Bedouin garb. Thus for his meeting with Feisal Hussein, in order to pay his respects, Chaim Weizmann famously posed with the Arab leader wearing the appropriate headdress. When T. E. Lawrence and Oppenheim met in 1912 at the ruins of Carchemish, on the border between modern Turkey and Syria, both wore Bedouin garb. The Englishman found Oppenheim to be “a horrible person” and later described him as “the little Jew-German-Millionaire who is making excavations at Tell Halaf.” During the war, Lawrence, himself a spy, kept a careful eye on Oppenheim.

If Lawrence looked askance at Oppenheim, Aaron Aaronsohn didn’t think much of Lawrence. They first met in the Arab Bureau at Cairo’s Savoy Hotel in 1917. At the time, Aaronsohn knew very little of the Englishman’s exploits and was not impressed: “At the Arab Bureau there was a young 2nd Lieutenant (Laurens)—an archaeologist . . . very well informed on Palestine questions—but rather conceited.” Given their very different political outlooks, a certain tension was inevitable. Lawrence did not think much of the Jews in Palestine, especially, as he later put it, the “German Jews, speaking German or German-Yiddish, more intractable even than the Jews of the Roman era, unable to endure contact with others not of their race.” Nor would Lawrence have approved of what Aaronsohn had written about the Arabs: “the man among them who will withstand a bribe is still to be found.”

Their second meeting—when both were at the successful height of their divergent activities—took place in late August of the same year and was even tenser. Aaronsohn told Lawrence that “the Jews intended to acquire the land-rights to all Palestine from Gaza to Haifa, and have practical autonomy therein,” upon which Lawrence lectured him on Palestine and the Arab mentality. Aaronsohn, whose knowledge of Palestine at the time was peerless, was aghast:

As I was listening to him, I could almost imagine that I was attending a conference by a scientific anti-Semitic Prussian speaking English. I am afraid that the German spirit has taken deeper roots in the minds of pastors and archeologists.

Lawrence argued that there was no future for the Jews in Judea and Samaria although there was a possibility for their settlement in Galilee. In the end, in any case, he added, even there the Jews would have to accept their fate: “If they are in favor of the Arabs, they shall be spared, otherwise they shall have their throats cut.”

For all that, Lawrence occasionally recognized the potential for mutual Jewish and Arab benefit within Palestine as a result of Zionist agricultural, industrial, cultural, and social development. Yet a document he drew up for Feisal predicted that if the Zionists with their “imperialistic spirit”—as opposed to the “old,” non-political Jewish population—would prevail, “the result will be a ferment, chronic unrest, and sooner or later civil war in Palestine.”

His remark about bribery notwithstanding, Aaronsohn, the militant Zionist, had surprisingly forward-thinking views on Arab-Jewish relations. As Ronald Florence and Patricia Goldstone have (perhaps over-optimistically) argued, had his vision been followed Arab-Israeli relations might have taken a more positive turn. Aaronsohn was acutely aware that any reasonable resolution of the conflict would revolve around the fair allocation of resources, especially water. The admittedly maximalist map that he presented at the Paris Peace Conference (of course without success) was one that created borders based on geographical rather than diplomatic-political considerations: the distribution of water resources, arable land, and transportation access.

There is one final, if highly speculative, irony to the Lawrence-Aaronsohn connection. Lawrence’s monumental autobiography, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, is dedicated to a mysterious “S.A.” There has been much speculation as to the identity of that person over the years. One particular theory, which went through various versions, held that the mysterious S.A. was none other than Sarah Aaronsohn with whom Lawrence was reputed to have had a torrid love affair. There were alleged assignations in Caesarea and elsewhere, but these stories have been shown to be entirely groundless.

Somewhat similarly, Scott Anderson provides few sources for the escapades of Minna Weizmann, so one must approach her story, too, with caution. At the very least, such stories add to the romantic aura that surrounds the period and its players.

Oh course, Lawrence, Oppenheim, and Aaronsohn were hardly the only operatives at work in and around Palestine. If some commentators have called Oppenheim a kind of counter-Lawrence of Arabia, there were a surprising number of actors on both sides who could make an even more convincing claim to that title. Wilhelm Wassmuss, who operated in Persia at the time, was actually called “the German Lawrence,” but, as Sean McMeekin points out, that title really ought to belong to Alois Musil, the second cousin of the famous Austrian novelist Robert Musil. A linguist, explorer, and archaeologist with a doctorate in theology, Alois Musil had traversed over 9,000 miles of the Arabian desert before the war. During World War I, he too donned Arab dress and consciously competed with Lawrence for Bedouin affection and the promotion of Ottoman holy war.

The same was true on the British side, for the exploits of St. John Philby (1885–1960), who may have been more “Lawrence” than Lawrence himself. A linguist—fluent in Urdu, Punjabi, Persian, and numerous Arabic dialects—he was also a dashing explorer. In 1932 and 1936 he undertook unprecedented desert treks. No other explorer, his biographer Elizabeth Monroe tells us, “had covered half as much of the huge surface of Arabia. None had drawn attention to so many of its antiquities; none had equaled his spread of maps.” In 1915 he was recruited to the Baghdad British administration to support the Arab revolt against the Turks and Germans, and protect the oil fields used by the British navy at Basra and Shatt al Arab. It was there that he learned the arts of espionage. In opposition to Lawrence and official British policy, he secretly favored and tirelessly, sometimes conspiratorially, worked for Ibn Saud over Sherif Hussein to lead the Arabs, which eventually led to his dismissal. Like Lawrence, he frequently donned Bedouin garb, though he remained in many respects a thoroughgoing Englishman. Unlike Lawrence, in 1930 he converted to Islam and married a Saudi Arabian woman.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Philby met with an assortment of Zionists including Chaim Weizmann, Moshe Shertok, and Lewis Namier. Ben-Gurion sought him out to probe Ibn Saud’s willingness to play a role in solving the Palestine issue. Most significantly, he conducted a series of negotiations with Judah Magnes about possible agreements with the Arabs. Their plan included a democratic constitution, protection of minority rights, and the interim maintenance of British mandatory rule. Though no Zionist, Philby was not interested in abrogating the Balfour Declaration, and supported the 1937 partition plan. After his disillusionment with Ibn Saud, Philby wrote rather presciently:

The true basis of Arab hostility to Jewish immigration into Palestine today is xenophobia, and instinctive perception that the vast majority of the central and eastern European Jews, seeking admission . . . , are not Semites at all. . . . [T]he European Jew of today, with his secular outlook . . . , is regarded as a stranger and an unwelcome intruder within the gates of Arabia.

Although he had often encouraged Arab war, Philby was strongly opposed to another war in Europe and turned sharply right in the late 1930s. He stood (very unsuccessfully) for election to parliament in 1939 for the far-right, anti-war British People’s Party, and was heard to compare Hitler to Christ and Muhammad. He was later arrested as a disloyal subject and interned under the Defence of the Realm Act. This, he claimed, was a confusion of policy criticism with national disloyalty. One does not want to foist the sin of the sons onto the fathers, but the final irony is that it was St. John Philby who recommended his son Kim to MI6 Deputy Chief Valentine Vivian for the British secret service. Philby, of course, became the most infamous double agent of the 20th century, but that story is well known.

Our narrative, like the historical and contemporary Middle East itself, is an endlessly messy one in which high politics, imperial machinations, mercurial visionaries, and scholarly spies played what John Buchan in his 1916 novel Greenmantle called “The Great Game.” The circumstances have changed but, it seems, the lethal competition goes on. Indeed, the germs of many of the problems that continue to vex us—jihadist fundamentalism, the fractured nature of the Middle East, the renewed dreams of a caliphate, the continuing, if less effective, role of the great powers, the unresolved Arab-Israel conflict, and the refueling of anti-Semitism—can all be traced to the period prior to, during, and immediately after the Great War. What role spies will play in all of this remains to be seen.

Suggested Reading

A Measure of Beauty

The Israeli hip-hop band Hadag Nahash blend the many strata of Hebrew language.

Israel’s TikTok Problem

Why has TikTok become a hotbed of anti-Israel and antisemitic content, and what does it tell us about brewing global conflicts.

Welcome to the Jewish Review of Books

Welcome to the first issue of the Jewish Review of Books.

What Goes Into Survival: A Report from the Washington Rally

People came by the hundreds of thousands, schlepping by train, chartered bus, overnight flight. Students raised money from relatives. Federations funded last-minute airfare. It was a rally for people who don’t attend rallies.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In