Adventure Story

The Story of Hebrew—really? Except for the imprimatur of a great university press, one might expect to find such a book in the young adult section of the library. But after reading Lewis Glinert’s witty and learned volume, I not only understand why he called it that, I’d be tempted to go him one better and suggest The Adventures of Hebrew. It’s a great story because there is nothing inevitable about it. Whether it was the period of the Bible or the Mishnah or Maimonides, there was always a danger, often the likelihood, that Hebrew would be lost in the break-up of great communities and subsequent migrations. That Hebrew managed to emerge from each crisis enriched is a fact we can appreciate only in retrospect. Each station along the way is, in fact, its own story thick with complications, suspense, and surprise.

The biggest surprise is that we have gotten the shape of the story all wrong. Because of the success of Zionism and Israel, Hebrew is the first language of several million people, and we tend to take that fact as the fulfillment of its destiny. A moribund, bookish tongue was finally given voice and sprang to life, redeemed. Make no mistake: The revival of Hebrew was indeed a miracle. But Glinert shows that in telling that story we have radically underestimated the importance of Hebrew as the matrix of Jewish literacy for almost two thousand years. Of the nine chapters in The Story of Hebrew, only the last is devoted to the “Hebrew State.” The marvel of “Hebrew reborn” (the title of Shalom Spiegel’s popular 1930 history) is not given short shrift, but Glinert places it in the context of the prodigious achievements and, yes, adventures of Hebrew along the tortuous and unpredictable road from the Bible to the eve of the Zionist revolution.

It is we Americans, I suspect, who are responsible for the disproportionate importance accorded Hebrew speech. Foreign languages come to us with such vexatious difficulty that when we hear Israelis chattering in Hebrew—how can they speak so fast!?—it is truly a wonderment to us. We have turned the thing we can’t do well into the chief marker of success. How many generations of parents have complained that after years of Hebrew school their children still can’t speak Hebrew, as if attaining a Jewish education hangs on that skill alone? And it’s not so different on college campuses, where Hebrew is taught not as the language of Jewish civilization but as the communicative medium of a country in the Middle East. The deck is stacked against us in America: In the absence of a Hebrew-saturated environment, the chances of achieving oral proficiency, alas, are almost nil.

But in the long view that Glinert offers us, speaking Hebrew plays a minor role. The last true speakers of Hebrew were the Judean survivors of the Roman wars in 70 C.E. and 135 C.E., who were sold into slavery or sought refuge in the Galilee. What saved Hebrew, along with Judaism as a whole, was both the preservation of textual memory and the creation of new texts. In the educational regime practiced under the Rabbis in the centuries after the destruction

of the temple, Glinert writes, “The knowledge of scripture—and the prodigious memorization of its intricate everyday applications—came to run deep and wide.” In addition to popular biblical literacy, there was the creation of the Mishnah, written in an entirely new expository style—concrete, balanced, methodical—that led directly to Maimonides and the lucid rabbinic classics of the Middle Ages.

Glinert presents the creation of the Mishnah—as well as the Hebrew prayers of the siddur—as a profound act of spiritual resistance to Greek, Latin, and Aramaic, the languages that dominated the Middle East for the thousand years before the Arab conquest in the 7th century. When Jews sat down to study the Bible or the Mishnah, they recited the text in Hebrew, but they surely spoke about the text in Aramaic, just as in most yeshivot today in America the text is discussed in English, even if it’s an English shot through with Hebrew terms:

In those times, unlike today, an everyday spoken language commanded minimal respect. What counted was whether a nation possessed a cultivated written language and a literary culture (read or memorized) to match. So it hardly mattered whether Jews continued to speak mundane Hebrew with their wives or children so long as Hebrew could go on functioning in Jewish sacred literature (oral and written) and people continued to understand and transmit it—which they did, imperfectly.

Yet resistance was not purism. The language of the Mishnah contains over a thousand Greek terms. When it came to matters of civil administration or the names of material objects, the Rabbis had no problem making use of other languages—think of Sanhedrin, that very Jewish institution with a Greek name—and this flexibility kept Hebrew supple and free of archaism.

I thought that I was well versed in the history of Hebrew, but there was hardly a page in this book on which I didn’t learn something new. And Glinert is a pleasure to spend time with; his authorial voice in The Story of Hebrew reminds me of those famous BBC radio talks given by enormously erudite Oxbridge dons: authoritative, amusing, and crystal clear.

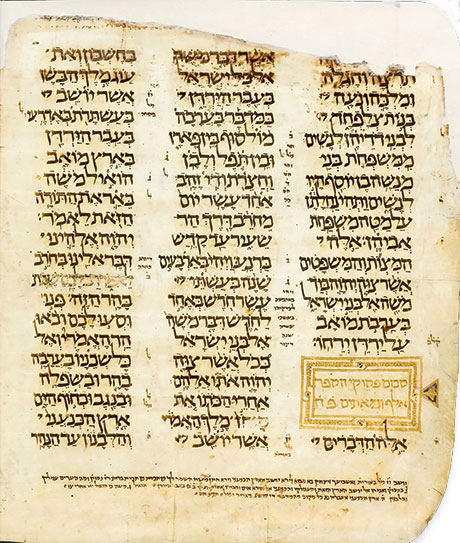

Take, for example, his account of the masorah. Masorah, or “transmission,” is the name given to the project undertaken between the 8th and 10th centuries to establish a stable, reliable text of the Hebrew Bible. I’d often seen these tiny scratch-like notations in rabbinic Bibles without giving them much thought. But, as Glinert explains, after the Arab conquest in the 7th century, Aramaic was rapidly eclipsed throughout the Middle East by Arabic and its alphabet. This made safeguarding Hebrew textual memory an even more urgent task. Variant manuscripts of the Bible abounded at the time, as well as multiple ways of dividing the verses, pronouncing the words, and chanting the text. Anyone who has stood before an open Torah scroll knows that there is terrifyingly little to go on in parsing the run-on blocks of text before you. We have several generations of the Ben-Asher family of Tiberias to thank for having provided the instructions both for reading the text correctly and for chanting it in the synagogue. These are the nikud, the vowel notations, and the ta’amei ha-neginah, the cantillation marks, all of which the Bar-Ashers were ingeniously able to fit in above and below each word. Our ancestors would have been lost if they had had to face the long night of exile without a common and useable text of the Bible provided them by these almost unsung Masoretes.

At about the same time in Baghdad, Saadia Gaon was mounting his own defense of Hebrew. Again, the issue was not spoken language; that role was ceded to Arabic. What was at stake for Saadia was the prestige of Hebrew as a language of culture, knowledge, and revelation. Hebrew not only lacked dictionaries and grammars, it had a tiny inventory of words as compared to Arabic. In the face of the claims of Islam made on behalf of Arabic as the perfect language, Saadia developed a counter-ideology centered on the concept of tzachut ha-lashon (language purity). After centuries of rabbinic discourse, he called for a return to biblical Hebrew for the high art of poetry as a font of Jewish creativity. Yet even as he defended the honor of an originalist Hebrew, Saadia absorbed and appropriated the Arabic way with language, whether it was poetic meter and genre or the rationalist endeavor to describe the underlying rules of a language. Where would Hebrew students be today if they didn’t understand how verbs are formed from tri-consonantal roots and then inflected according to a series of paradigms called binyanim?

Saadia and the Masoretes made contributions that are still felt today by students of Hebrew, but Glinert does not neglect the curious episodes that left little mark on present-day Hebrew. For instance, not only was the medical wisdom of the Middle East preserved by Byzantine Jews, but we have records of over five hundred translations into Hebrew of Greco-Arabic medical texts by more than 150 translators. In the 9th and 10th centuries, moreover, Hebrew was the official language of instruction in the medical schools of Provence. Then there is the case of Christian Hebraism, which is less an episode than a story unto itself, one that Glinert tells very well. The fact that more than half of the Christian Bible is written in Hebrew meant that translators of scripture into Latin and European vernacular languages often were forced to rely on Jews for their intimate knowledge of the holy tongue. Yet rather than fostering gratitude or kinship, this dependence was often begrudged.

The Puritans in New England viewed themselves as new Israelites and their colonies as a new Canaan; the Hebrew names they gave to their children (Ezra, Abigail) and to their settlements (Goshen, Salem) are evidence of the role played by Hebrew scripture in their cultural imagination. Yet over and over again the prestige enjoyed by the Hebrew language as the vehicle for God’s word failed to neutralize the animus felt toward flesh-and-blood Jews for their stiff-necked adherence to a superseded religion. The strangest episode in this part of the story is probably the case of Christian Kabbalah:

This new kabbalism focused not on worship of God but on mystical enlightenment and the limitless powers that gnosis or esoteric knowledge could grant to man. Manipulations of the Hebrew language, speculative numerology, and other theurgic techniques promised practitioners limitless intellectual power, untrammeled by the Church.

“Christian kabbalism,” notes Glinert, “could be said to have supplied much of the intellectual confidence that underwrote modern science.” This is not an understatement; its students included Francis Bacon, Giodarno Bruno, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Isaac Newton.

Glinert shows that the revival of Hebrew as a modern literary language, first in Germany at the end of the 18th century and then in Eastern Europe at the beginning of the 19th, long preceded the first Zionist Congress in 1897. Hebrew was revived in order to serve as a vehicle for the modernization of the Jewish people before it was connected to the idea of a return to the ancestral homeland. For the great writers of the time—Bialik, Tchernichovsky, Ahad Ha-Am—Hebrew was primarily a language in which to explore the displacements of traditional religion by modernity. True, they ended up in Palestine, but only after events in Russia left them little choice. Hebrew had been revived as a national language replete with poetry, satire, novels, and newspapers while Zionist politics were still in their infancy. Moreover, it was Hebrew as—to adapt Heine—a portable homeland that powered the youth movements and Tarbut schools in interwar Europe and the Hebrew colleges and summer camps in America.

No chronicle of the revival of Hebrew would be complete without an appearance by its reputed star: Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. Even now, Hebrew school students can conjure up the image of Ben-Yehuda feverishly creating new words and raising his son in a hermetically sealed Hebrew environment. Here too, Glinert offers a useful corrective:

Running a home in Hebrew remained a fringe proposition for some time, but Ben-Yehuda enjoyed greater success with another groundbreaking idea: Hebrew as a language of instruction. Here he drew on the so-called direct method for teaching language by immersion, which became all the rage among British educators in the 1880s. Ben-Yehuda was the first to attempt it with Hebrew; soon thereafter, other teachers in fledgling Zionist villages like Petah Tikva and Rehovot followed his lead. . . . By 1898, twenty elementary schools were operating fully or partly in Hebrew, attracting twenty-five hundred pupils, or almost one in ten children. In that same year came the first Hebrew kindergarten. Children were beginning to speak Hebrew with their friends in the schoolyard and, critically, with younger siblings in the backyard. Hebrew was going native—a mother tongue without mothers.

Although it was Ben-Yehuda who set the ball rolling, it was actually the school teachers who were responsible for the revolution.

While telling the tale of Hebrew, Glinert keeps an eye on its sibling, Yiddish. And here is another surprise: Yiddish saved Hebrew from shriveling into its own self-seriousness. The maskilim, who championed the Hebrew Enlightenment in the early 19th century, sought to revive Hebrew as an august literary language, the language of Moses’s declamations and David’s songs. But the high Hebrew they wrote turned out to be incapable of representing lived reality. That’s where Yiddish came in. The early 19th century was also the period of the greatest spread of Hasidism. Although Hasidic leaders such as Nachman of Bratslav delivered their homilies to their followers orally in Yiddish, their teachings were quickly translated for publication into the prestige Jewish language, Hebrew. This simple, lively, and unpretentious Hebrew became an important stylistic resource for writers who sought a way around the stilted, ornate Hebrew of the maskilim.

This debt went largely unacknowledged when the language wars between Hebrew and Yiddish heated up in the years before World War I. That battle was eventually decided by outside forces. Millions of Yiddish speakers perished in the Holocaust, while Hebrew flourished in the Yishuv and the State of Israel. Although Yiddish was the first language of many of the citizens of the new country, Ben-Gurion insisted on the suppression of Yiddish in official life in the country and refused to allocate resources to the preservation of its culture. A similar policy was pursued in the case of the Arabic- and Farsi-speaking Jews in the early years of the state. By the time of the great Russian aliyah in the 1990s, the government had learned its lesson. It did not stand in the way of Russian-language schools and TV programming. Perhaps the socializing power of Hebrew had been underestimated all along, since the children of Russian immigrants opted for Hebrew anyway. For better or worse, they lost their Russian at just about the same precipitous pace that the children of Israeli immigrants to America lost their Hebrew.

Despite the pressure exerted by English as a global language, Hebrew is remarkably resilient. By now, most haredim conduct their lives in Hebrew rather than Yiddish, and it is the fully functional second language of the large Arab minority too. Word creation continues to happen in wholly unpredictable ways. Ben-Yehuda’s awkward compound word for telephone Sach-rachok never made it, but machshev for computer has become universal. The Academy of the Hebrew Language proposes, and the body of everyday Hebrew speakers disposes. Never has Hebrew been written and heard in more wildly divergent registers, from the slang of hip-hop DJs and sports announcers through the argot of the IDF and on to the prose of gritty novels, ethereal poetry, and profound Torah commentary.

But only in Israel. Can we in the diaspora do anything but bask in its linguistic glory? Here too, the story Lewis Glinert tells has something to teach us. Our ancestors sustained, and were sustained by, the cultural and religious riches of Hebrew, even when it was not their spoken language. Perhaps it is time for us to follow their example.

Suggested Reading

Begin’s Shakespeare

Memories of Israel's early prime ministers, by the man who wrote their speeches.

Eight Poetic Fragments by Avraham ben Yizhak

Some of Abraham Sonne's lines are so gorgeous that one commits them to memory almost unthinkingly.

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

The Idea of Abrahamic Religions: A Qualified Dissent

What is "Abrahamic" about Judaism, Christianity, and Islam?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In