Of Spies and Centrifuges

In April 2009, a young Iranian, Shahram Amiri, disappeared in Medina, Saudi Arabia. Ostensibly there to perform the hajj, Amiri had in fact brokered a deal with the CIA to provide information on Iran’s nuclear program. Leaving his wife and child behind in Iran and a shaving kit in an empty Saudi hotel room, Amiri fled to America, received asylum, pocketed $5 million, and resettled in Arizona. Formerly a scientist at Malek Ashtar University, one of several institutes harboring Iran’s nuclear endeavors, Amiri conveyed the structure of the program and intelligence about a number of key research sites, including the secret facility at Fordow.

The story might have ended there. But according to Jay Solomon, chief foreign affairs correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and author of The Iran Wars, what happened next “emerged as one of the strangest episodes in modern American espionage.” A year after Amiri defected, he appeared on YouTube, claiming that the CIA had drugged and kidnapped him. In fact, Iranian intelligence had begun threatening his family through their intelligence assets in the United States. Buckling under that pressure, Amiri demanded to re-defect. In July 2010, he returned to a raucous welcome in Tehran, claimed he had been working for Iran all along, and reunited with his son. Of course this was not the end of the story. Amiri soon disappeared, and in August 2016, shortly after Solomon’s book was published, he was hanged.

Amiri’s saga exemplifies the kinds of stories that Solomon tells throughout his account of the U.S. struggle with Iran. Amiri was just the latest victim in 30 years of spy games between the United States and Iran, a conflict, Solomon writes, “played out covertly, in the shadows, and in ways most Americans never saw or comprehended.” The Iran Wars draws on a decade of Solomon’s Middle East reporting to trace that history, urging readers who are caught up in centrifuge counts and sanctions relief to view Iran’s nuclear build-up as part of its broader clash with the United States—and sometimes between the United States and itself.

Solomon’s book appeared in the waning days of Obama’s presidency, as a first-take history of the American–Iranian nuclear negotiations. Yet in the wake of Donald Trump’s surprising ascension to the presidency, it’s newly relevant—now not as a summation but as a starting point. Few within the GOP support the Iran deal, but intra-party debates have emerged on how to move forward. Many critics of the deal eagerly await its demise, while others grudgingly insist on honoring it with strict enforcement. These differing viewpoints appear to exist within the Trump administration itself.

By distilling years of play-by-play news into a coherent narrative, sprinkled with vignettes from Solomon’s extraordinary reporting in the Wall Street Journal, the book offers a basis for reestablishing common facts and chronology as a new administration confronts the long-bedeviling dilemma of Iran. In that sense, it is a blueprint for the Trump team’s reevaluation of the Iran deal—whether to preserve it, and if so, how.

Solomon begins his chronicle in the weeks and months following September 11, 2001. As the United States launched its campaign to root out al-Qaeda from Afghanistan, it quickly discovered the footprints of foreign powers—not just India and Pakistan, but Iran. CIA operatives working with the Northern Alliance, which had been founded with the aid of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), were told to keep a low profile as they neared the front lines, to avoid detection by Iranian observers. For several months, Washington and Tehran felt their way toward some form of détente in Afghanistan. But as Solomon reports, early confidence-building measures collapsed under long-standing suspicions and duplicitous Iranian behavior, which extended to harboring al-Qaeda fugitives, including Osama bin Laden’s son.

The same pattern repeated in Iraq. Initial engagement with Iranian envoys, including the future foreign minister, Javad Zarif, soon dissolved into mutual misgivings. Solomon criticizes the Bush administration for failing to understand the level of existing Iranian influence in Iraq, and for failing to prepare for the complex religious and tribal schisms that Tehran would exploit. Even before the war, Iran began drawing on its local influence, “lying in wait,” according to Solomon, for the United States to fall into its trap. While many U.S. officials hoped that the Iraq war would weaken the Islamic Republic, its leadership launched a bid for hegemony so rapid that few recognized it and so ambitious that both sides of Iraq’s civil war received its support. Iranian meddling deepened Iraq’s endemic dysfunction and proved deadly for U.S. forces.

Iran has deployed this strategy of sectarian gamesmanship across the Middle East. Over the last decade, its agents have seemed to be everywhere; in Lebanon, their powerful proxy, Hezbollah, assassinated Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and crushed the Cedar Revolution, and in Syria, as Solomon puts it, Damascus “became the forward operating base for Iran’s Axis of Resistance.” Throughout, Tehran continued to bewitch Washington with a brew of cooperation and competition. Even as Iran undermined U.S. interests across the region, many continued to see it as a potential ally.

Those forces within the American foreign policy community had little to stand on while Iranian-supplied explosives maimed U.S. troops in Iraq. But if they couldn’t reach the ayatollah, they’d aim for Bashar al-Assad instead. They hoped that they could reel the Syrian dictator out of Iran’s orbit, potentially generating a series of foreign policy achievements. In 2006, then-Senator John Kerry defied the Bush administration and traveled to Damascus to meet with Assad. The next year, Nancy Pelosi followed Kerry to Syria’s capital. When President Obama took office, Solomon writes, “Assad emerged as a central target of Obama’s new diplomacy,” with Senator Kerry spearheading the outreach.

The attempt to wean Syria away from Iran foreshadowed Obama’s later attempt to wean Iran away from itself. Solomon largely holds his rhetorical fire in The Iran Wars, but he reserves special scorn for Kerry. The senator, he writes, dined at five-star Damascus restaurants with the Assads and returned home to proclaim Bashar a “progressive” ruler who understood “his young population’s desire for jobs and access to the Internet.” In another sign of things to come, Kerry was particularly taken in by the smooth-talking Syrian ambassador to the United States, Imad Moustapha. The ambassador “engaged in a crafty diplomatic dance” in Washington, lambasting Israeli policies but regularly meeting with Jewish figures and singing songs of Syrian moderation. Even as Assad began butchering Syrian civilians in 2011, Kerry praised Moustapha publicly and declared his continued belief that “Syria will change”—showing, in Solomon’s words, “a troubling lack of judgment” that “raised questions about his ability to read the intentions of world leaders.”

Kerry and others would later trade in Assad for Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, and Moustapha for Rouhani’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif. In the meantime, however, the regional struggle between the United States and the Islamic Republic increasingly centered on Iran itself—and especially on its burgeoning nuclear program. In the months before the Berlin Wall fell, the Iranian government had already begun preparing the way for its nuclearization. Solomon retells that story by focusing on the key figures, such as Ali Akbar Salehi, who would later play a major role in securing Iran’s nuclear future by negotiating with the United States. In one of the several spy-novel twists featured throughout The Iran Wars, Solomon recounts how Iran recruited a former Soviet nuclear scientist, Vyacheslav Danilenko, who was an expert in designing nuclear detonators. Over the course of their six-year partnership, Danilenko helped the Iranians design their explosives testing facility at Parchin—ground zero for Iran’s attempts to weaponize its nuclear operation.

As Iran put the final touches on Parchin in 2002, an Iranian opposition group, the Mujahedin-e-Khalq, held a press conference in Washington revealing the scope of Iran’s nuclear ambitions. In an episode that Solomon curiously glosses over, European powers, with tepid American acquiescence, soon started negotiations with Iran to freeze its nuclear development. In the wake of the lightening U.S. victory in Iraq, Iran agreed to suspend its nuclear enrichment, the only time it agreed to do so in a dozen years of diplomacy. But by January 2006, at the nadir of American involvement in Iraq, Iran had broken its commitment.

From that point forward, the Bush administration adopted steadily intensifying financial measures to compel Iran to choose between having an economy and having a nuclear program. Orchestrated by Stuart Levey, the undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence at the Treasury Department, the effort at first focused on blocking tainted Iranian financial institutions—those facilitating terrorist and nuclear activities—from obtaining access to the U.S. dollar. Solomon describes Levey’s “global road shows” to Arab, Asian, and European capitals to persuade banks that conducting business with Iranian firms would harm their own access to the U.S. financial system. Over the next three years, the Treasury Department wove together a boa-like blockade of the Iranian financial system that increasingly suffocated the Islamic Republic’s economy.

When the Obama administration took office, however, it slowed Levey’s offensive in order to initiate an aggressive diplomatic outreach. Just months into his term, the new president dispatched two letters to Ayatollah Khamenei that immediately took regime change off the table; he also slashed funding for democracy-promotion initiatives in Iran. His commitment to finding a path forward with Iran’s ruler remained so strong that, rather than back the millions-strong Green Revolt that arose in 2009, Obama remained silent. Only when a subsequent round of nuclear negotiations collapsed did Obama resume the sanctions push, and only then reluctantly—spurred in part, as the book details, by the fear of a unilateral Israeli attack. Despite the administration’s attempts to water down subsequent sanctions legislation, Solomon admiringly reports that Treasury’s war “proved singularly lethal,” amassing unprecedented financial leverage against the Islamic Republic.

By 2013, the pressure became so severe that Iran’s new president, Hassan Rohani, knew he needed access to the more than $100 billion in frozen oil revenues sitting in banks abroad. The only way to do so was through negotiations. Yet just as Iran began to buckle, the Obama administration seemed to become even more eager to deal. Solomon devotes the final portion of The Iran Wars to the two-year diplomatic dance that followed, eventually resulting in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

Public negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 (the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, plus Germany) resumed amidst the palaces and hotels of old Europe; the French begged for a harder line, while Ayatollah Khamenei demanded that Iran retain an industrial-sized nuclear enrichment program. The real work, however, took place backstage. Quiet feelers through an Omani back channel that commenced in 2009 blossomed into full-fledged secret diplomacy once Rohani took office. The United States and Iran fleshed out the terms of the deal, largely imposing them on the rest of the parties. Along the way, Solomon writes, the United States angered its allies, issued empty threats to walk out of the talks, and “started significantly departing” from its original strategy while “weakening its terms.” Only a last-minute series of cave-ins secured the final agreement, which, at best, delayed Iran’s nuclearization by 15 years.

At what cost? Solomon devotes much of his book to searching for an answer. The deal’s constraints, he grants, “offer an opportunity to calm the Middle East.” But the deal also leaves open a path to nuclearization that risks “unleashing an even larger nuclear cascade” across the region. And, most crucially for Solomon, it does nothing to address the issues that produced the Iran wars in the first place—namely, the violent, anti-American aggression of Tehran’s theocrats. In hot pursuit of an arms accord, the Obama administration downplayed or accommodated crises generated by Iran, arguing that it needed to prioritize the nuclear issue. At least some within the administration seemed to hope that the accord would provide the solutions to those very crises. This wishful expectation, if not outright contradiction, could, Solomon believes, lead to a “much bigger and broader war” bubbling up between Iran, its adversaries, and likely the United States.

Solomon’s insights are piercing, but unfortunately he clouds them in the way that he chose to structure The Iran Wars. Rather than covering the many facets of the U.S.–Iranian struggle chronologically, he divides them into discrete sections—Afghanistan, the Iraq war, the Arab Spring—frequently rewinding the clock to detail the events. He also devotes a great deal of his attention to areas outside of the nuclear negotiations, so much so that he doesn’t turn to the nuclear program until a third of the way through the book. Although this approach succeeds in recontextualizing the relationship between Washington and Tehran, it sometimes decontextualizes the nuclear negotiations themselves. Readers rarely see, for example, how an Iranian action in Iraq might have influenced a U.S. negotiating position in Switzerland. Solomon makes a strong case for the need to comprehend the relationship between the broader U.S.–Iranian battle and the nuclear talks, but he sometimes obscures the very connections he has done so much to reveal.

Nonetheless, Solomon has excavated many of the deeper patterns that underlay the nuclear diplomacy. In the process of seeking to empty Iran’s centrifuges of nuclear isotopes, the Obama White House loaded them with psychological meaning, and the impulses that drove Washington’s misbegotten entreaties to Damascus reemerged. John Kerry, whose role in The Iran Wars is as a kind of diplomatic Don Quixote, dashed around the region, proposing to visit Tehran in 2009 and floating massive U.S. concessions without full White House approval. The new Imad Moustapha in his life, Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif, responded by tweeting “Happy Rosh Hashanah,” an act of ecumenism that reportedly astonished Obama staffers. A sweet greeting here, a moderate move there; the Islamic Republic’s rhetorical morsels fed an insatiable American appetite for fantasies of a Tehran transformed.

Yet those fantasies weren’t simply about Iran. They were also about redefining America’s role in the world. For key figures in the administration, the nuclear talks represented something much more than preventing the spread of nuclear weapons. “What was interesting about Iran is that lots of things intersected,” one of Obama’s chief aides, Ben Rhodes, told Solomon. From nonproliferation to the Iraq war, several currents of American foreign policy “converged” around Iran, making it not only a “big issue in its own right, but a battleground in terms of American foreign policy.” President Obama seemed to believe that history was trending in America’s direction and that the best approach was to avoid needless confrontations that could interrupt that process. If the goal was for the United States to get out of history’s way, the greatest threat to that project was the Iranian nuclear crisis. The possibility of war, after all, meant the possibility of America imposing itself once again in the Middle East and on the globe.

The prospect of American action against Iran was just as likely to materialize as a result of a unilateral strike by Israel, which would almost certainly draw in U.S. forces. This explains why the Obama administration so feared Israeli action—a fear that in some ways defined American diplomacy with Iran. Solomon refers to Washington’s anxieties about Jerusalem several times throughout his story, but The Iran Wars may underemphasize Israel’s role in the moral and political calculus behind the Iran deal. One senior policymaker indicated its centrality when, after much progress in the talks, he famously described Benjamin Netanyahu to Atlantic writer Jeffrey Goldberg as a “chickenshit.” “He’s got no guts,” the official said, while another called Netanyahu a “coward” who had succumbed to the administration’s pressure and failed to bomb Iran when he could. Central members of the president’s team seem to have gone out of their way to taunt the prime minister of a close ally in the heat of sensitive, multiparty nuclear negotiations.

Whether calculated strategy or revenge-fueled gloating, the leak signified that Obama’s nuclear diplomacy was almost as much a contest of wills with Israel as it was with Iran. For generations, a strong U.S.–Israel relationship embodied and necessitated American leadership in the region; downgraded ties signaled a reduced regional role for the United States, with the added benefit, for some administration officials, of weakening the pro-Israel lobby in the United States. As much as, in Solomon’s words, Obama “wagered” on eventual Iranian reform, he also wagered that the deal would prevent the “blob,” the long-standing foreign policy experts of both parties, from reversing the administration’s new course in the region.

The question moving forward, of course, is whether President Obama succeeded, particularly with regard to Iran. During the campaign, now-President Trump consistently criticized the Iran nuclear agreement, calling it a “terrible deal,” and warning that Iran would no longer get away with humiliating U.S. forces in the Gulf. He repeated those criticisms after the election and once in office, telling Bill O’Reilly that the nuclear accord was “the worst deal I’ve ever seen negotiated” and arguing that it had “emboldened” Iran. “They follow our planes, they circle our ships with their little boats, and they lost respect because they can’t believe anybody could be so stupid as to make a deal like that,” he said in February. The administration quickly backed that rhetoric with action. Following an Iranian ballistic missile test and an attack on a Saudi warship by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen, then-Trump National Security Adviser Michael Flynn put the Islamic Republic “on notice,” and the White House imposed a new round of sanctions on Iranian individuals and entities.

At the same time, Trump has pulled back from his threat to tear up the agreement, telling O’Reilly that “we’re going to see what happens.” And those who might have advocated for such an approach are no longer in Trump’s direct orbit. Flynn, whom many saw as the most hawkish force on Iran within the administration, resigned in February, leaving behind those seemingly more inclined to honor the deal with strict enforcement, including Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, long the most vociferous foreign critic of the agreement, appears to seek a more muscular U.S. posture as opposed to full cancellation. Although it remains too early to say how all of the internal and external dynamics shaping the administration’s Iran policy will develop, Trump certainly harbors no emotional or political attachment to the nuclear deal.

Yet the larger question posed by the JCPOA is its overall effect on U.S. foreign policy. The Obama administration’s negotiations with Iran, and its broader quest to solve several global problems at once, are part of a recurring pattern in U.S. diplomatic history. From Cairo to Baghdad, Democratic and Republican presidents alike have looked to foreign capitals for salvation-sized solutions to regional crises, hoping that winning over a leader or signing a peace agreement could touch off cascading successes. Such expectations have generally led to disappointment. The Iran Wars is relevant now not just as a valuable synthesis of the history of U.S–Iranian relations, but also as a warning against the risks of such domino diplomacy, no matter how seductive.

Suggested Reading

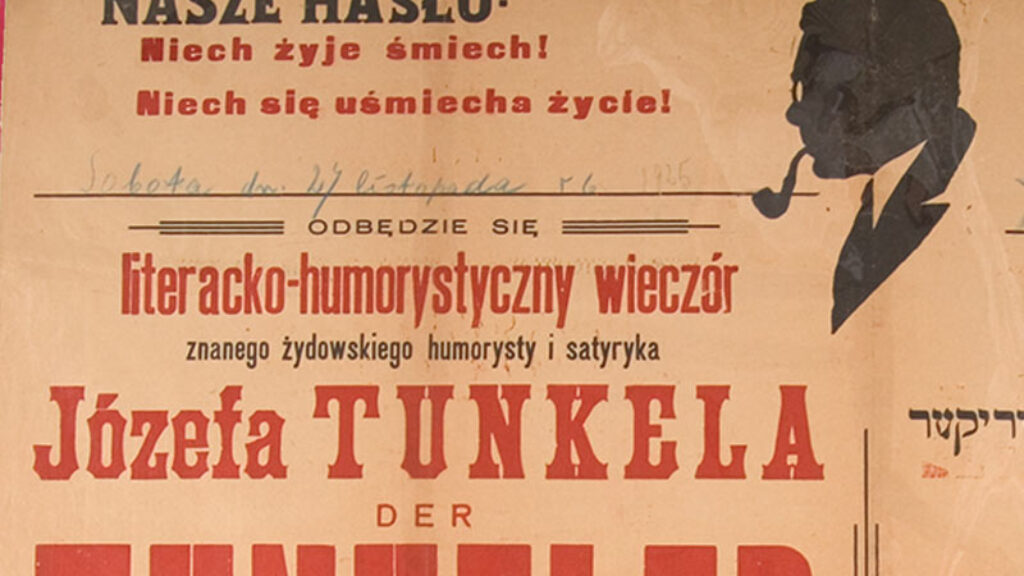

Spinoza in Warsaw: Fragments of a Dream

“Having rested in his grave for 250 years, Baruch Spinoza came to the conclusion that just lying around like that was without telos” and decided to try to make it in Warsaw. A Yiddish satire, translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

When Eve Ate the Etrog: A Passage from Tsena-Urena

There was once a custom for a pregnant woman to bite off the tip of the etrog at the end of Sukkot. This excerpt includes the text of a Yiddish prayer, or tkhine, that the pregnant woman is instructed to recite based on an interpretation of Genesis 3:6.

A Sharp Word

From his intensive study of Hebrew and Jewish history to a surprisingly romantic Zionist congress in Basel, and the horrors of the Kishinev Pogrom, 1903 seems to have been a turning point for the young Jabotinsky.

Category Error

What is lost when the books of the Hebrew Bible are read as philosophy?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In