What If Everyone Is Right?

In his last speech as an active member of the Knesset, David Ben-Gurion warned his country’s political establishment about a dilemma into which he feared it was likely to fall:

The Six-Day War created new trends or what seem to be new ones: [that of] lovers or seekers of peace, and [possession of] the whole land of Israel. I don’t know to which of them I belong. I was for both things all my life, and I’ve been in many parties. . . . These two things, peace and the whole land of Israel, as long as they were attainable and possible, I supported them wholeheartedly . . . and therefore I don’t see any contradiction between these two things. It’s not two parties but two different situations.

What Ben-Gurion meant to say was that people’s attitudes toward the territories taken in 1967 should not be ideological or theological. The disposition of these territories was a practical question, and the decision about them should depend on what was realistically possible. What mattered most was ensuring the existence of the state, the nature of the peace that would be offered to Israel in exchange for a withdrawal, and the demographic situation.

Almost 50 years later, the publication of a new, best-selling book by Micah Goodman, Milkud 67 (Catch 67), shows just how right—and how wrong—Israel’s first prime minister was. Ben-Gurion was certainly right to fear that Israel would be split into two, as it has been, over the question of what, in April of 1970, were still newly acquired territories. But he was wrong to dismiss this difference of opinion as unnecessary, since one’s stance with regard to the territories is never simply a matter of tactics. When an Israeli says that he is for, or against, the division of the land, he inevitably says many things about his identity, culture, world view, degree of religiosity, and more.

Catch 67, whose title is an obvious riff on Joseph Heller’s Catch 22, is about the implications and consequences of Israel’s control, since 1967, of, if not exactly the whole Land of Israel, then at least those parts of it that made up the Palestine Mandate until 1948. Goodman’s book is one of the rare instances in which a work of serious non-fiction becomes a genuine best-seller, and deservedly so. In Israeli bookstores on the 50th anniversary of the Six-Day War, Catch 67 plumbs the ideological and historical depths of the arguments of both the right and the left, treating them with equal respect.

In June parliamentarians Ayelet Nahmias-Verbin and Yehuda Glick invited Goodman to discuss his book in the Knesset. What is particularly striking is that this invitation came jointly from representatives of the two camps into which Ben-Gurion did not wish to see the country split. Nahmias-Verbin, a member of the Zionist Camp (formerly the Labor Party), first entered politics in the 1990s under the aegis of Yitzhak Rabin and is an ardent supporter of the two-state solution; Glick, a member of Likud, is an American-born Orthodox rabbi best known for his forceful advocacy in recent years of Jews’ rights to worship on the Temple Mount. Only as brave and impressive an attempt as Goodman’s to address all the arguments for and against withdrawal in a deep and serious manner, anchoring them in Jewish history and philosophy, could evoke such an unusual bipartisan response. Goodman himself lives in the West Bank town of Kfar Adumim, but, as he explained in an interview with Isabel Kershner of the New York Times, “I would rather not be called a settler. It’s where I live, not who I am.”

In a small country with its fair share of public intellectuals, Micah Goodman is an extraordinary figure. He holds a PhD in Jewish philosophy from the Hebrew University and has an impressive ability to make complex works of Jewish thought accessible and relevant to the Israeli public. His three previous books about Judaism, including one translated into English under the title Maimonides and the Book That Changed Judaism, have all found readers and reviewers from a variety of perspectives. Secular and liberal readers appreciated a religious standpoint that did not threaten them, while people from the religious camp were pleased to see Goodman revive public discussion of Jewish classics.

Goodman has a somewhat unusual background that may in part account for his readiness to try to understand both sides: His mother was born into a devout American Catholic family. One of her uncles was a personal assistant to Pope John Paul II, but she converted to Judaism, became an Orthodox Jew, and immigrated to Israel with her husband following the Six-Day War. Goodman grew up in Jerusalem, received a religious education, and later obtained a doctorate in Jewish philosophy at the Hebrew University. In an interview with the “Walla!” website three years ago, following his receipt of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies’ Liebhaber Prize for Promotion of Religious Tolerance, he said that “as a child I thought that every Jewish child has a grandmother who speaks to Jesus.”

No less erudite than his earlier books, Catch 67’s most basic insight is that what separates Israelis and Palestinians, first and foremost, are feelings of fear and humiliation deeply rooted in history. The Israelis are stronger, but the experience of the Jews in the diaspora has inclined them to be afraid that their adversary, in the current case the Palestinians, is always just waiting for an opportune moment to attack. The Palestinians, for their part, feel humiliated, not only because of the IDF’s control of the territories but more fundamentally because of the low status of Muslims in the world since the decline of Islamic civilization. In other words, according to Goodman, the conflict is a religious one but not theological. It is a result of the historical experiences of Israeli Jews and Palestinian Muslims.

Goodman is less concerned, however, with religious history than he is with political history, and in the first part of his book he explains how the Israeli right and the Israeli left have come to their present positions. According to his account, the blend of territorial maximalism and political liberalism that once characterized the right boiled down in the face of intifadas and demographic challenges to liberalism pure and simple. But when such third-

generation “princes” as Ehud Olmert, Tzipi Livni, and Dan Meridor thus abandoned the “Greater Land of Israel” part of their heritage, they didn’t leave the field empty: “A different ideological group came to dominate the right and breathed a new life into it: the messianic religious right.” The conception of the whole land of Israel as one that had been promised to the Jews by the international community gave way, or rather returned, to the idea of the land promised by God. Goodman writes that while “at the outset, the dominant group on the right placed human rights at the center of things, by the end of the 20th century the dominant group on the right placed redemption at the center of things.”

Goodman’s account of what has happened on the right is accurate enough, even if he gets some historical details wrong. Thus, he presents Vladimir Jabotinsky’s 1910 article “Homo homini lupus” as evidence of his belief in man’s untrustworthy nature. This, he says, underwrote the Revisionist party founder’s certainty that the British would eventually betray the Zionists. He overlooks, however, the extent to which Jabotinsky actually persisted in placing his hopes in the British. He also ignores that the fact that when Menachem Begin, Jabotinsky’s eventual successor, proposed in 1938 to launch “military Zionism,” which would lead to direct conflict with the British, it was Jabotinsky who objected and said that he still believed in the conscience of the world.

As for the left, Goodman argues that from the 1920s to the 1970s it didn’t make peace a central goal: The great shift in the ideological focus of the left took place in the 1970s. The left relinquished its dream of the model socialist society and took up the dream of peace: “Instead of solidarity among workers there would be solidarity among nations.”

Goodman is correct to point to ideological change on the left, but I think that what has actually occurred is rather different than what he describes. From the outset, the socialist left sought to reach an agreement with the Palestinian workers on the basis of shared class interests. It likewise believed that the entire population of Palestine would benefit from the economic prosperity that the Jews would bring to the land. Only after the anti-Jewish riots in 1929 did the mainstream of the left grasp that this hope was baseless. Following the publication of the Peel Commission’s report in 1937, Ben-Gurion led the left to favor partition as the only practical basis for compromise.

When Goodman turns from the ideological evolution of Israel’s political parties to their current positions with respect to the most pressing issues facing the nation, he is equally attentive to both sides. The right, he acknowledges, is correct to insist that there is no going back to the 1967 lines, since Israel needs control over the highlands overlooking its coastal plain, where the bulk of its population lives:

A descent of the IDF from the mountains of Judea and Samaria would create a vacuum that could draw into it all the chaos of the Middle East, and situate it on the edge of Tel Aviv.

Yet the left is also correct when it claims that it will be impossible to preserve Israel as a Jewish and democratic state without separation from the Palestinians. Although he carefully labels the Palestinian Arabs’ high birth rate a demographic “problem,” and not, as is so common in Israel today, a “time bomb,” Goodman is deeply worried that the Jews will soon cease to be a majority in their own land. He does, to be sure, give plenty of attention to “alternative demographers” on the right who maintain that both the numbers of Palestinians today and their birth rate are lower than is generally believed. But even if they are correct, Goodman argues, and the number of Arabs on the West Bank is 1.65 million and not 2.3 million, “can one absorb such a large Arab population without rocking the State of Israel?” Preserving Israel as “the national state of the Jewish people depends not only on maintaining a Jewish majority but on maintaining a solid and strong Jewish majority,” and that would cease to be possible if the Arab population of the state were to be practically doubled.

Goodman doesn’t hesitate to use the word kibbush (literally conquest, but in the Israeli lexicon the equivalent of “occupation”) to describe Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria, and he is perfectly prepared to call the occupation immoral—but only in a qualified sense. It is immoral, he says, to hold sway over the land’s non-Israeli inhabitants, who like all people have the right to govern themselves. But the West Bank itself cannot be deemed to be “occupied,” since Israel took control of it in a defensive war against Jordan. And Jordan itself had seized it in a war—and not a defensive one—against Israel in 1948. Israel is under no obligation, therefore, to return the territories, since “a world in which there is no price to pay for aggression is a dangerous world, one in which bullies don’t have to face any risks.”

What Goodman emphatically rejects is the idea that Jewish law should be the determining factor here. Goodman maintains that halakha itself gives priority to considerations of security and must take its bearings by them. After expressing a strong historical attachment to the land, he reminds his readers that ownership of it is conditional.

The return to the land of the prophets also has to be a return to the vision of the prophets, and an Israeli society that fulfills the biblical tidings is measured by its stance toward minorities, foreigners, and others who are different. The relations between the State of Israel and the Arabs who are under its jurisdiction afford the people of Israel an opportunity to fulfill the biblical vision, but they also place before it a challenge that one can fail to meet. Military government of a civilian population, which has continued for decades, since the Six-Day War, is an Israeli religious failure. The prophetic vision of a powerful society that is sensitive to the weak is shattered every day by the IDF’s policing of the barriers in the territories.

What is problematic from the point of view of the Bible also contradicts the original spirit of Zionism. Herzl, in his Altneuland (Old-New Land), states that “all people deserve a homeland.” Doesn’t Zionism contradict itself, therefore, when “it enslaves another people”?

Goodman concludes the second part of his book with a quick summary of the ways in which everyone is in the same boat:

Presence in the territories fulfills Zionism and goes against Zionism; retreat from the territories fulfills prophetic Judaism but chips away at the national identity; a presence in the territories protects Israel geographically but threatens it demographically. It seems that everyone is right, and because everyone is right, they’re all trapped.

If Goodman had ended his book at this point, he would probably still have received applause from both ends of the spectrum. But he chose to leave his intellectual “comfort zone” and present a practical solution of his own. What he proposes is a limited arrangement in which Israel would withdraw its military presence as much as possible from most of the territories in order to grant the Palestinians as much freedom as possible without allowing for a completely independent state. At the same time, Goodman says, Israel must continue to hold on to the Jordan Valley as its eastern border. This would enable it to maintain its defensive position in those parts of Israel necessary for its security but end as much of its “occupation” of the lives of the land’s non-Jewish inhabitants as is compatible with Israel’s strategic needs.

Goodman’s solution is based on deep thought and analysis, and he is not the only one who believes that at the present time there should be no expectation of a comprehensive peace. But it is hard to ignore the fact that at bottom, although Goodman emphasizes that this wasn’t his intention, he seems to end up agreeing with Benjamin Netanyahu’s decision not to decide. Moreover, as he himself admits, none of the Palestinians with whom he has spoken has agreed to accept a limited agreement of the sort he has proposed.

Goodman’s book has met with a storm of discussion and criticism in Israel. Undoubtedly the most significant of the responses to his book came from a figure who plays a notable part in it: former prime minister Ehud Barak. Somewhat astonishingly, the man who sought—and failed—to achieve an end to the conflict when he was prime minister in 2000 descended to the pages of Ha’aretz to publish a long review of Catch 67 in May 2017. In the essay, he accused Goodman of creating a false symmetry between the left and the right and characterized him as being, despite his posture of impartiality, wittingly or unwittingly, a rightist in disguise. Barak’s main argument was that Israel could, in fact, defend itself even if it were to withdraw from the territories, but in the absence of such a withdrawal there is no hope for sustaining a Jewish and democratic state. According to Barak, the demographic problem is a strategic one. The security problem is technical and has tactical and technical solutions.

Naturally, Barak’s criticism caused a stir and generated further interest in the book. Goodman was not intimidated. “Why does Barak say that I have a right-wing agenda?” he asked a week later. “Because I am ready to take the right’s arguments seriously. Why do right-wingers say that I am a leftist? Because I take seriously the arguements of the left as well.” He went on to observe that “denying the security dangers of a territorial withdrawal sounds no less absurd to most Israelis than denying the demographic problem sounds to Barak.”

This wasn’t the only confrontation in which Goodman found himself. A review in the popular Israeli newspaper Yediot Achronot also blamed him for being a right-winger in disguise, while the indubitably right-wing minister of education, Naftali Bennett, deplored Goodman’s sympathy for the arguments of the left on Facebook, though he also praised the book’s depth.

At one point in Catch 67, Goodman recollects that the Talmud preferred the house of Hillel to the house of Shammai, not because its adherents were more correct in their halakhic opinions, but because they were willing to listen to the arguments of the other side before expressing their own position. In doing so, he is reminding his fellow Israelis, who like to argue more than they like to listen, of an old but still refreshing lesson. Needless to say, Goodman’s book won’t bring an end to what has long been our most urgent national conversation, but it does demonstrate, by both precept and example, how best to participate in it.

Suggested Reading

Letters, Fall 2021

We and I; It's a Novel: An Exchange

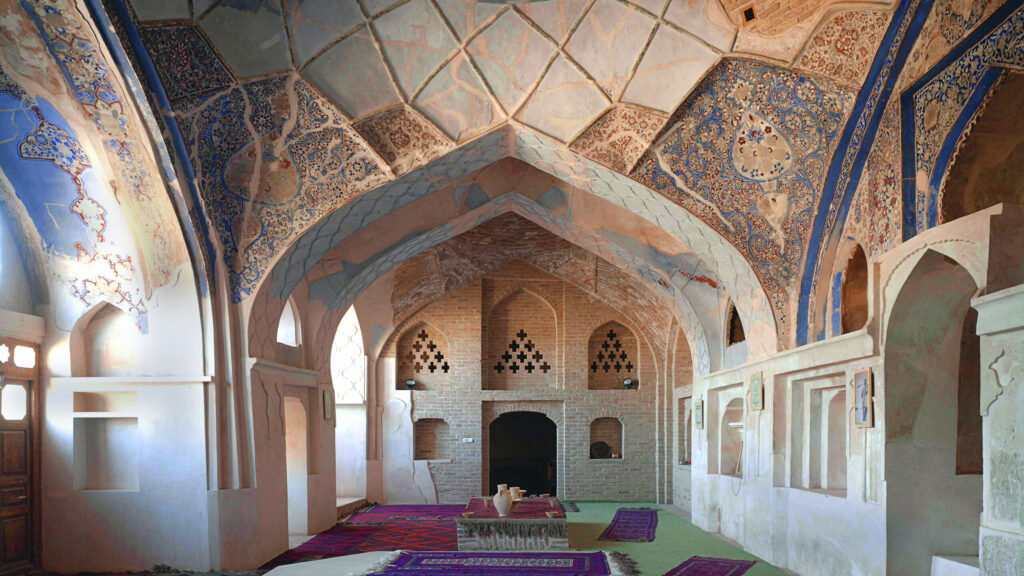

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Lawfare

What's the trouble with the international laws of war?

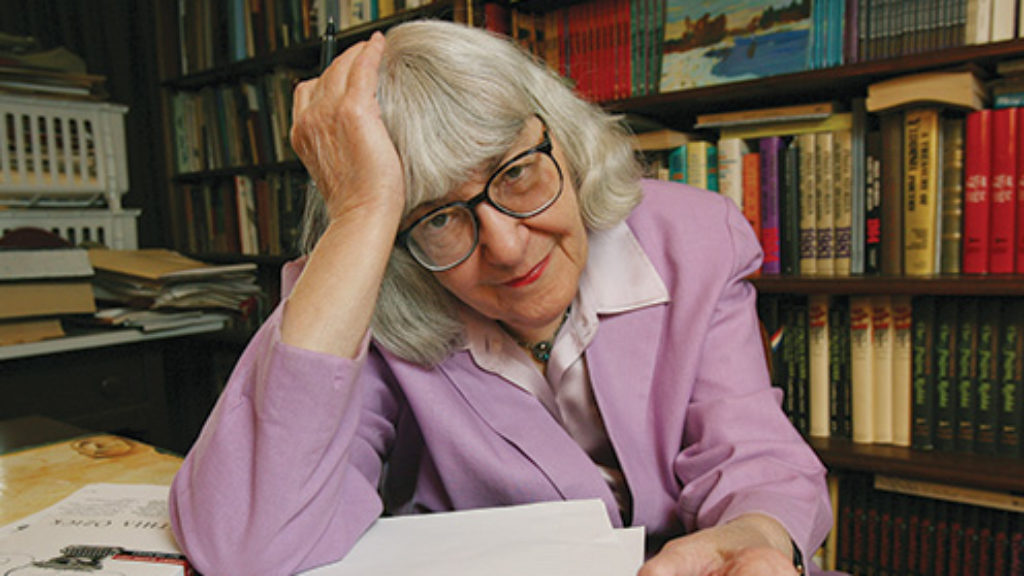

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In