Journeys Without End

Diana Trilling was a celebrated 20th-century writer, a literary critic, an essayist and memoirist, and an energetic participant in her era’s countless ideological controversies. She was also the wife of Lionel Trilling, who could be described as the greatest mid-century American critic. Theirs was an intellectual marriage. It was creative and fraught, and from their private conversation arose two distinct public careers, though, according to biographer Natalie Robins, Diana Trilling was not just a discussant and editor of her husband’s work. She was an unacknowledged co-author, a muse who sat behind the typewriter.

Robins develops this thesis throughout The Untold Journey: The Life of Diana Trilling. Robins’s title is an allusion to an allusion to an allusion. Lionel Trilling borrowed the title of his 1947 novel, The Middle of the Journey, from the celebrated first line of Dante’s Divine Comedy about finding oneself in a dark wood at the middle of life’s journey. Diana Trilling, in turn, punned on the title of her husband’s novel in the title of her memoir of their marriage, The Beginning of the Journey, published after his death in 1975. Diana’s journey was not exactly untold; indeed, she was fond of telling it, but never has her story been so extensively narrated as it is in The Untold Journey.

Lionel Trilling and Diana Rubin were both born to middle-class Jewish families in 1905. They met in New York in their early twenties and married in 1929. Lionel launched an illustrious academic career at Columbia in 1932, rising to eminence in the late 1940s through essays on politics, society, and culture that were equally timely and timeless. Drawing on interviews with Diana as well as on extensive archival material, Robins argues that by the mid-1930s, Diana Trilling was already her husband’s writing partner.

Proximity to Lionel helped Diana begin her own career, and for some three decades the two Trillings shared a limelight that was not quite identical but never entirely separate. When Lionel passed away in 1975, Diana became even more productive, publishing two books and scores of essays. She died a well-known figure in 1996.

For Robins, the Trillings’ marriage was a vehicle of unending psychic tension. Notoriously abrasive, Diana was once banned from a grocery store in her New York neighborhood. She suffered from depression. So too did her husband, who was prone to lacerating self-doubt and private fits of rage. Sharing a fascination with Freud and the possibilities of therapy, they placed their child, James, in analysis when he was just seven years old. “‘Which of us was sicker?” Diana plausibly wondered about herself and Lionel.

Robins makes Lionel’s psychological sickness the backbone of her biography. At the conclusion of her book, she paraphrases the argument of a 1999 American Scholar essay by James Trilling, “My Father and the Weak-Eyed Devils,” in which James retrospectively diagnosed his father with attention deficit disorder (ADD), a serious judgment Robins accepts at face value. (It is difficult to think of a 20th-century writer whose prose showed fewer signs of deficient attention.) Had Lionel Trilling been a healthier man, he might not have had such terrible writer’s block; he might have depended less on the ministrations of his gifted wife, and, consequently, might have resented his wife less. Theirs might have been a less tortured journey, although Robins rightly doubts that Diana Trilling “would have accepted an ADD diagnosis.” Freudian that she was, “neurosis was her verdict of choice.”

The Untold Journey is a document of our own therapeutic culture, and as such it is a missed opportunity. The Trillings were much larger than their psychological difficulties. They stood at the center of an extraordinary 20th-century milieu, rooted in New York City and awash in art and ideas. They lived through political and intellectual upheavals, and, in the process, fashioned unique authorial voices, most alert and alive at the point where fiction and non-fiction meet. Lionel’s literary-intellectual journey has been evaluated many times. Diana’s has not. It deserves a wider latitude than it receives in this somewhat claustrophobic biography.

Diana, who traveled in Europe as a child, was the product of “well-to-do metropolitan Jewish society.” Both she and Lionel were the children of Eastern European Jewish immigrant families, but theirs was not the world of the working-class Yiddishkeit so lovingly recreated by Irving Howe. The world of Diana’s and Lionel’s fathers was more genteel and more assimilated. Diana attended Radcliffe College; Lionel went to Columbia. Robins goes so far as to note Diana’s “secret desire to be a Catholic.” Yet they married in a traditional Orthodox ceremony and retained an enduring sense of themselves—morally and culturally—as Jews.

As with Lionel, Diana’s true religion was art. Their first apartment was in Greenwich Village, where they lived across the street from Edmund Wilson. Untethered to academia, Diana was less wedded to high culture than her husband. She was eager to extract the social and political insight contained within contemporary works of fiction and cinema and in the lives of those producing these works.

Her political evolution was remarkable. She graduated from the apolitical 1920s into the intensifying radicalism of the Red Decade. She and Lionel would attend political meetings at 16th Street and Irving, during which they stood and sang “the International with clenched fists raised in the air.” In her radical heyday from 1930 to 1932, Diana served as a secretary for a communist front organization, brushing up against the Soviet espionage activities that would be obsessively revisited by Senator McCarthy and his acolytes in the 1950s.

By 1945 Diana was an outspoken liberal anti-communist. The 1930s had immersed her in the personal as political and in the political as personal, which made her an intriguing commentator on second-wave feminism. She was a “family feminist” in her self-description, willing to defend the traditional family, while at the same time a pioneer of women’s rights. The contradictions and richness of her position were on full display when she appeared on stage with Norman Mailer and Germaine Greer for a raucous 1971 debate on feminism in New York’s Town Hall, which became the subject of a documentary by D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus called Town Bloody Hall, and, more recently, a play.

This was politics as pure theater, and Diana Trilling had a crucial role as a representative of the older generation and qualified defender of Mailer. At the debate, she made an amusing case for human complexity and limitations in revolutionary times, arguing that “as an added benefit of our deliverance from a tyrannical authority in our choice of sexual partners, or in our methods of pursuing sexual pleasure, I could hope we would also be free to have such orgasms as in our individual complexity we happen to be capable of.” Hers was one of the least zany performances.

Diana was adamant, finally, about not being a neoconservative. She did not endorse either Richard Nixon or Ronald Reagan, and it was, in part, politics that destroyed her friendship with Midge Decter and Norman Podhoretz, a beloved student and protégé of Lionel’s. Likewise, Diana’s affection for Irving Kristol and Gertrude Himmelfarb, who had been political allies in the 1950s, dimmed in the 1970s.

Although Diana may have co-authored Lionel’s books and essays, as Robins claims, there is one circumstance that complicates the story, rendering Robins’s theory of co-authorship less certain and less meaningful. Lionel was one kind of writer: elliptical, cerebral, allusive, a teacher who drew the reader forward toward unexpected conclusions precisely because the teacher’s words were not the last word. He was a clear-headed virtuoso of ambiguity. For Lionel Trilling, to provide an answer was to violate the question. Only Lionel Trilling could have written a book of essays titled The Opposing Self, and only he could have prefaced it with the following words: “I speak of the relation of the self to culture rather than to society because there is a useful ambiguity which attends the meaning of the word culture.”

“The modern self,” he goes on, “is characterized by certain powers of indignant perception which, turned upon this unconscious portion of culture, have made it accessible to conscious thought.” What begins in the first person quickly cascades into a series of widening abstractions (meaning, culture, the modern self) which modify one another, seasoned with the delightful antinomies of a power of perception that is indignant, of the cultural unconscious lending itself to conscious thought, and of an ambiguity that is, of all things, useful.

This was not Diana’s style. She had aspired to be an opera singer in her youth, and she knew how to project her voice, which was direct, intimate, concrete, and opinionated. She was an observer who did not mind weighing in or levying judgment. If the beat-generation poets were too unkempt for polite society, she would say this out loud and in print, as she did in her marvelous 1959 essay about a poetry reading of Allen Ginsberg’s, “The Other Night at Columbia.”

For me, it was of some note that the auditorium smelled fresh. The place was already full when we arrived; I took one look at the crowd and was certain that it would smell bad. But I was mistaken. These people may think they’re dirty inside and dress up to it. Nevertheless, they smell all right. The audience was clean and Ginsberg was clean and Corso was clean and Orlovsky was clean.

Here, the sensory perception frames the author’s own awkward squareness, exaggerated to the point almost of campiness, while at the same time satirizing the beat-generation poets who champion the dirty and the disheveled and the dangerous but are nevertheless shockingly clean. This is literary criticism without any abstraction at all.

Diana Trilling’s best writing was often about her personal experiences. It was writing that moved through vividly captured details: the six martinis that Lionel consumed before dining with the Kennedys at the White House, the exotic customs and dress of Camp Lenore and her remembered childhood summers in the Berkshires, her descriptions of the luxurious kitchens Radcliffe students enjoyed in the 1960s compared to the formal teas she and her classmates attended in the 1920s.

In assessing Diana as a writer, Robins alights on an observation that deserves more sustained attention and analysis: Her essays belong to the genre of New Journalism, blending reportage with cultural commentary and doing so exuberantly in the first person. After all, Diana was friends with Norman Mailer and Truman Capote, two eminent practitioners of New Journalism. (Diana and Lionel attended Capote’s legendary Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel, where Lionel, age 61, danced the night away.) She was also friends with William F. Buckley Jr., whose journalism was no less personality-driven than Capote’s or Mailer’s.

As a stylist, Diana had more in common with Norman Mailer than with her husband. Her personal life lacked the violence and the anarchy for which Mailer wished to be famous, but the tableau of ideas and images, captured in first-rate prose over a long stretch of historical time, makes Diana interesting in the same way Mailer remains interesting. Ambitious New Yorkers with a front-row seat to American culture, they moved in and against the culture around them. The puzzles, pleasure, and pain of the Lionel–Diana marriage pale by comparison with the city outside their apartment door, and with the times in which they lived, all of which is vividly reflected in Diana’s essays and books. She generated and loved controversy, as Mailer did and the ambivalent Olympian Lionel Trilling did not. Once the controversy was there, it could be contemplated and written about. Diana Trilling should be read and remembered as a unique character and chronicler of the American century.

Suggested Reading

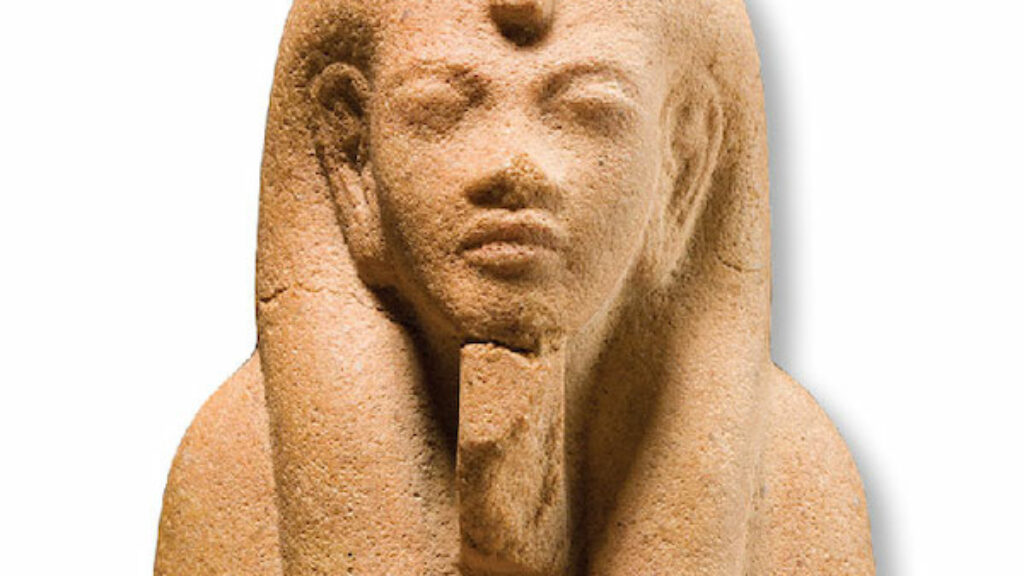

Moses, Murder, and the Jewish Psyche

Sigmund Freud had always identified with Moses. At the end of his life, as the Nazis rose to power, he returned to the Bible and the origins of the Jewish psyche. We all know his scandalous theory—or do we?

Manufacturing Falsehoods

An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other.

Kibitzing in God’s Country

It may come as a surprise that there is an entirely different Catskills, a Catskills that doesn't involve Grossinger's, bungalow colonies, or Jews, in the words of Billy Crystal, eating "like Vikings."

I’m Still Here

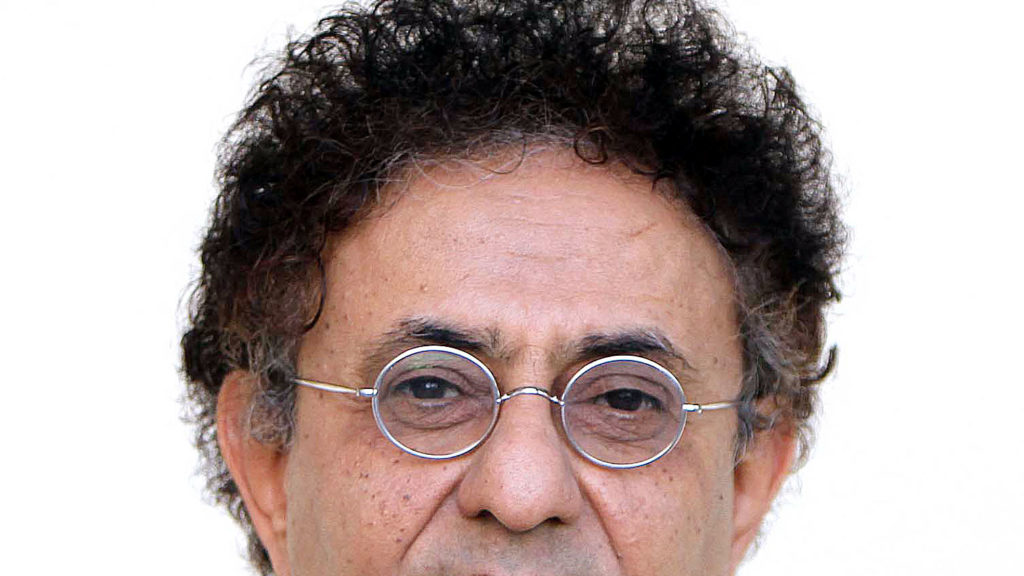

Tuvia Reubner has said he has no homeland except perhaps his poetry. A new book expands that homeland's borders.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In