Straying from the Fold?

Many people know that the late archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger (1926–2007), was born and raised as a Jew, but fewer know that this was also true of Jerusalem’s first Anglican bishop, Michael Solomon Alexander (1799–1845), a native of Posen (now Poznań) in Prussian Poland. Both bishops make brief appearances in Todd Endelman’s engagingly written and wide-ranging new book, Leaving the Jewish Fold: Conversion and Radical Assimilation in Modern Jewish History, but only the latter is mentioned in its chapter on “Conversions of Conviction.” Unlike Lustiger, who was raised by secular Bundist parents and baptized as an adolescent in wartime France, Alexander—originally Pollack—had received a sufficiently advanced Jewish education to serve, after arriving in England, as a cantor and ritual slaughterer in Norwich, Nottingham, and Plymouth in the early 1820s.

In an earlier book, Radical Assimilation in English Jewish History, 1656–1945, Endelman noted that Alexander’s baptism, at St. Andrew’s Church in Plymouth, was attended by more than a thousand people. Although Alexander was included in a chapter Endelman called “The Fruits of Missionary Labors,” his first exposure to the New Testament actually came from a pious Jew whose children he was tutoring. “My employer was a man of strict integrity,” Alexander wrote in his spiritual autobiography, “and strongly attached to the principles and ceremonies of Judaism.” It was this man who warned him about English missionaries, saying that “every Jew ought to read the New Testament, in order to be more confirmed in his own religion.” This aroused Alexander’s curiosity, but “not being able then to read and understand English,” he instead “procured a German Bible” and was “greatly struck with the first of St. Matthew,” having had “no idea that Christians knew anything of our patriarchs.” The future convert “was still more struck,” he later reported, “with the character of Christ, and the excellent morals which he taught.”

Alexander concluded his brief autobiography by extending “sincere thanks” to his “Jewish friends, whose kindness towards me I shall ever remember,” adding that despite his awareness “of being an outcast from them, yet I trust I shall never be unmindful of them before a throne of grace in my feeble prayers.” Such sentiments of Jewish solidarity were not uncommon among converts such as Alexander. The Reverend Hatchard, whose sermon on the occasion of Alexander’s baptism was published together with Alexander’s autobiography, assured “the Christian public that with the exceptions of some verbal expressions, the whole of the above statement was composed by Mr. ALEXANDER, without the aid of any friend.” The historian must, needless to say, approach such assurances with a measure of skepticism, but must also consider the danger of throwing out the sincere convert with the baptismal waters.

Endelman, in his introduction to Leaving the Jewish Fold, states straightforwardly—a bit too straightforwardly for my taste—that “most Jews who became Christians in the modern period . . . were insincere.” Later, he writes that “[w]ith few exceptions conversion was a secular rather than a spiritual act.” For the majority, Endelman asserts, conversion was “a strategic or practical move, much like changing a name or altering a nose.” This, of course, was hardly true of Michael Solomon Pollack, who would become Bishop Alexander, his name change notwithstanding. If we are to understand the complex history of Jewish conversion to Christianity, we must try to understand the specifically religious experience and motivations of the converts as well as the social desire to merge with the majority.

The chapter Endelman devotes to “Conversions of Conviction” does open with an acknowledgment that “[a]mong the many Jews who became Christians in the modern period were a few who were, by their own testimony and the testimony of others, sincere converts.” But the majority, he insists repeatedly, “changed their religion to escape the disabilities of Jewishness.” His book is much stronger on the disabilities of Jewishness than it is on the motives for and process of conversion to Christianity. Those disabilities, as Endelman reminds us, often continued even after a formal break with Judaism had been made—either by converts themselves or by the Jewish parents who baptized them. “As Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81), Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), and thousands of less well-known converts discovered,” he writes, “the world continued to regard them as Jews long after they became Christians.” This social reality was exacerbated “[w]hen racial thinking became respectable in the nineteenth century.” That pseudoscientific world has recently been revealed by Mitchell Hart in his valuable collection Jews and Race: Writings on Identity and Difference, 1880–1940. Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu, one of the thinkers mentioned in that anthology, wrote, for example, that even in Heine’s simplest songs there was “something at once sad and spiteful, an after-taste of tears, an acrid flavour, a sting of maliciousness, due to his origin, his education, and the position then occupied by the Jews in Germany.” The poet, claimed Leroy-Beaulieu, was the “last flower” of German romanticism, but a diseased one “with an unwholesome odor; for in this German rose there lurks a worm—Judaism.”

To his credit, Heine never denied that “worm.” In 1827, some two years after Heine had been baptized, he replied to a relative who inquired about his well-being, “Allen Meschumodim soll zu Mute sein wie mir” (all apostates should feel as wretched as I do). Despite the irony, Heine often did feel wretched about his frankly mercenary conversion and expressed surprise at former Jews of independent means, such as the composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847), who took their Christianity seriously. Endelman quotes a pungent remark of Heine’s about Mendelssohn, who had been baptized by his parents as a child. “If I had the good fortune to be the grandson of Moses Mendelssohn, I would never employ my talents to set the urine of the Lamb to music.” The lamb in question was, of course, Jesus. Susan Jacoby, in her recent Strange Gods: A Secular History of Conversion, suggests that Heine was alluding to Mendelssohn’s role in reviving Bach’s sacred music. Indeed, in 1829 Mendelssohn organized the first public performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion since the composer’s death nearly eight decades earlier, to which I would add that Mendelssohn’s cantata “Christe du Lamm Gottes” was first performed in 1827, though published only posthumously.

In contrast to Heine, Disraeli, and Mendelssohn, none of whom ever made a secret of their Jewish origins, later in the 19th century increasing numbers of former Jews sought to hide their origins. “From the 1870s,” writes Endelman, “ideological antisemitism, occupational discrimination, and social exclusion . . . combined to create an atmosphere in which increasing numbers of Jews in Europe and America experienced their Jewishness as an unbearable burden.” Endelman is particularly good at using statistical evidence to demonstrate regional differences. In cosmopolitan Berlin the annual average of conversions to Christianity rose from one for every 1,500 Jews during the years 1872–1881 to one for every 650 in the following decade. In Catholic Vienna the rate was higher, “largely,” as Endelman notes, “because of the absence of civil marriage.” Intermarriage itself could often soothe the otherwise “unbearable burden” of Jewishness. As to the nature of that burden, Endelman aptly quotes the Jewish protagonist of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1908 novel The Road into the Open, set in the author’s native Vienna: “[W]hen a Jew behaves crudely or comically in my presence, sometimes such a painful feeling seizes me that I want to die, to sink into the earth. . . . It’s exasperating that one is continually made responsible for the mistakes of others.” Motivated, in many cases no doubt, by such ethnic shame, more than 3,300 Viennese Jews converted between 1897 and 1902, but even in fin de siècle Vienna other motives existed.

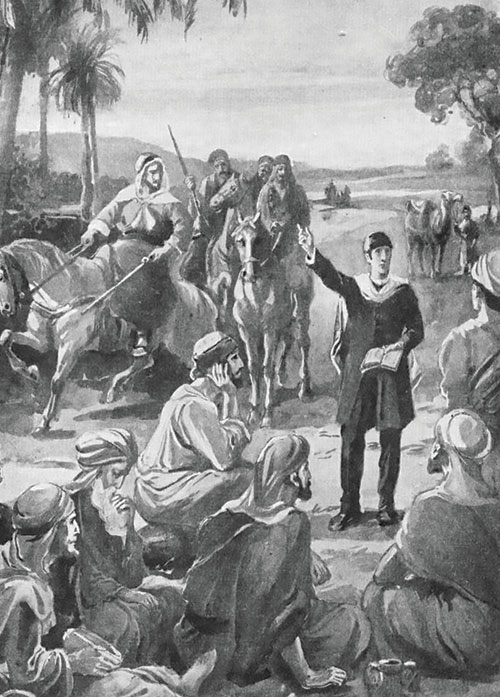

Endelman briefly mentions “the eccentric Joseph Wolff (1795–1862), son of a Franconian rabbi, who traveled extensively in the Near East and Central Asia for the London Society and published accounts of his harrowing adventures.” Although Endelman composed the excellent entry on Wolff in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, in Leaving the Jewish Fold we are told nothing of his missionary activity and adventures, which would have given the reader a sense of the lived experience and career of a sincere convert and Christian missionary.

In 1821 Wolff met a young Jew named Jonas in Gibraltar with whom he debated the meaning of Jacob’s blessing to Judah in Genesis 49:10 and to whom he offered a Hebrew New Testament, “but he answered me that he already had one.” Instead, Jonas was given “a copy of the Psalter, and Tremellius’s [Hebrew] Catechism.” In September of that year Wolff arrived in Cairo, where there were many Italian Jews and where he “distributed a great many . . . Italian New Testaments.” In Jerusalem, to which he soon continued, Wolff claimed to “have given Hebrew Bibles and [New] Testaments, and Tremellius’s Catechism, to twenty-seven rabbies [sic].” He may, of course, have been exaggerating, and some of those “rabbies” may have taken the books in order to remove them from circulation. Indeed, in his account of a subsequent visit to Jerusalem in the late 1820s—accompanied by his new wife Lady Georgiana Walpole (sixth daughter of the seventh Earl of Orford)—Wolff acknowledged that “the Jews burnt several of the New Testaments I gave to them.” Still, his writings show what modern missionaries hoped to accomplish. No less important, they also reflect the missionary practice of distributing Hebrew Bibles of the sort most 19th-century Jews had never seen. These editions, from which Rashi and other traditional commentators were absent, made it easier to debate the meaning of such controversial passages as Jacob’s blessing in Genesis 49:10 and the “suffering servant” of Isaiah 53 with Jews who could not easily recall their traditional rabbinic interpretation.

Wolff quoted that famous verse in Genesis during a visit to the Ionian island of Kefallinia (Cephalonia), then under British rule, in 1828. When introduced to a Jew named Jacob, he replied “Jacob said, ‘The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come; and unto him shall the gathering of the people be.’” He then addressed the city’s Jews as a whole: “My dear Sons of Abraham! I am your brother according to the flesh, a son of Abraham . . . Your Adonai is my Adonai.” Interestingly, Wolff went on to urge the Cephalonian Jews not to “believe those Christians who tell you that you have no longer to expect to be restored to your own land, or the future personal reign of the Messiah . . . upon Mount Zion,” asserting that this was “a most grievous error against Moses and the Prophets, and the New Testament.” He then added that he could not “pass over in silence those prophecies which speak of that same Messiah in a state of suffering before His coming in glory,” or those “which have predicted your unbelief in Him.” This was followed by a lengthy exposition of Isaiah 53.

Later, in Alexandria, he returned to his Christtian vision of Jewish redemption: “[T]he time is approaching that our nation shall be gathered again by the omnipotent arm of the living God . . . and restored to their own land . . . not to be removed for ever.” Referring repeatedly to “our nation,” Wolff drew upon some of the more erotic expressions in the prophetical books concerning God’s relationship with Israel, asserting that “[t]he time is approaching . . . when our nation shall be again the spouse of God, so much beloved in other times, whose desolations and afflictions . . . will move the heart of her husband . . . and reconciled to her, he will recall her to her ancient dignity, and receive her with the warmest welcome.” He was, in certain respects, more of a religious Zionist than a radical assimilationist.

Wolff’s repeated visits to such cities as Alexandria and Jerusalem remind us to what degree the history of Jewish conversion to Christianity in Europe—at least in the 19th century—was closely linked with the Middle East. Although Leaving the Jewish Fold is subtitled Conversion and Radical Assimilation in Modern Jewish History Endelman chose to omit “the not-unknown phenomenon of Jews becoming Muslims in the lands of Islam,” which requires, he modestly asserts, “a historian with training and expertise that are different from mine.” Leaving out “the lands of Islam” leads him, however, to devote insufficient attention to the many Jews, including no small number of European Ashkenazim, who converted to Christianity in the Holy Land and its environs. One suspects that they are under-represented in Endelman’s study not only because their conversions took place in the Ottoman Empire, but because those conversions were rarely instances of “radical assimilation.”

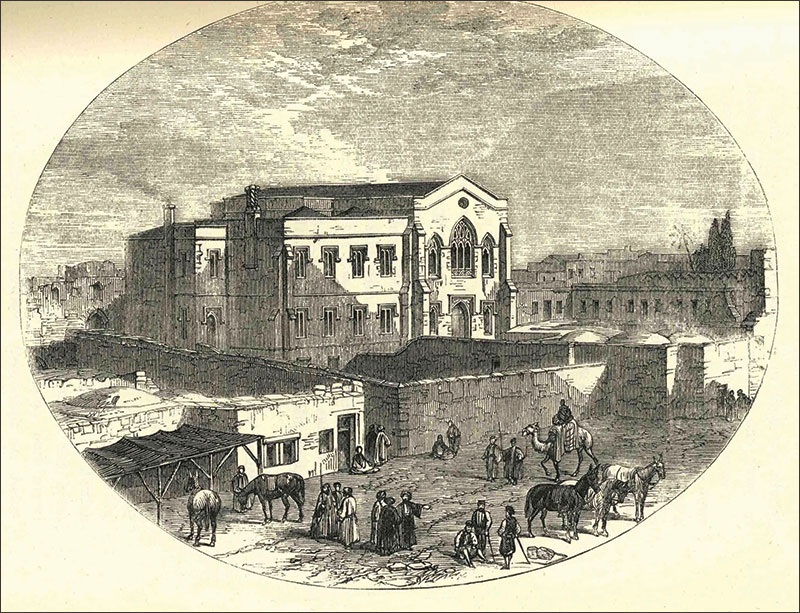

Alongside Joseph Wolff and Michael Solomon Alexander, another Central European–born convert to Christianity whom Endelman might have profitably treated at more length is Ridley Haim Herschell (1807–1864). He does tell us that in 1842 Herschell was instrumental in founding the (Nonconformist) British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Among the Jews, but does not mention Herschell’s journey a year later to the Middle East, described in his moving travelogue A Visit to My Father-Land, Being Notes of a Journey to Syria and Palestine in 1843. Of “the long-expected moment” of first seeing Jerusalem he wrote, “The feelings of such a moment cannot be described; they can only be faintly imagined by those who have not experienced them. Every Christian traveller speaks of the feeling as overpowering: what, then, was it to me, as at once a Christian and a Jew!”

One of the highlights of Herschell’s stay in Jerusalem was being present at the baptism of four Jews in a Hebrew ceremony conducted by Bishop Alexander. A few days earlier, Herschell had met Erasmus Scott Calman, a Latvian Jew who had been baptized in England and soon afterward traveled to the Middle East, where he worked as a missionary for the London Society, mostly in and around Jerusalem. In 1840 Calman published a monograph under the provocative title Some of the Errors of Modern Judaism Contrasted with the Word of God. Nonetheless, in that same year he and Alexander signed a public statement composed by the missionary Alexander McCaul that firmly rejected the recent ritual murder accusation in Damascus. “We the undersigned, by nation Jews . . . but now by the grace of God members of the Church of Christ,” it read, “do solemnly protest that we have never directly or indirectly heard of . . . the practice of killing Christians or using Christian blood,” condemning the charge as “a foul and Satanic falsehood.” Although Endelman discusses the laudable efforts by Alexander and McCaul, no mention is made of Calman, who retired to London in 1858 and upon his death in 1890 left a considerable sum, as reported in the Times, “to found a charity for poor and deserving Hebrew Christians of both sexes, including deserving Gentile widows of Hebrew converts.”

Another fascinating figure who might have appeared among Endelman’s “Converts of Conviction” is Ferdinand Christian Ewald, who was Bishop Alexander’s personal chaplain in Jerusalem. In his Journal of Missionary Labours in the City of Jerusalem, During the Years 1842-3-4 he wrote of the baptism witnessed by Herschell: “This morning, at a special Hebrew service . . . Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Benjamin, Isaac Hirsch, and Simon Fränkel, were baptized by the Bishop in the holy tongue.” Eliezer, whose surname was Luria and who took the baptismal name Christian Lazarus, had experienced considerable opposition from family members—including his wife, who herself later converted. A second “Rabbi Benjamin,” who became John Benjamin Goldberg, was later sent by the London Society to Cairo. The life stories of these two convert-missionaries complicate the neat dichotomy between conversion to Christianity in modern Europe and conversion to Islam in the Middle East. Both had been baptized in Jerusalem by a bishop who was, like them, of Ashkenazi background, and both remained in the region as missionaries. And, whatever their failings, neither they nor Ewald, whose heart had filled with “holy joy” at their baptisms, fit Endelman’s brisk enumeration of typical Jewish converts ensnared in the nets of Protestant missionaries: “Swindlers, thieves, drunkards, whores, schlemiels, schlemazels, nudniks, and no-goodniks.”

It doesn’t fit Isaac Hirsch, later known as Paul Isaac Hershon (1817–1888), who was also baptized by Bishop Alexander that day, either. Hershon, a native of Buczacz in Galicia, had arrived in Jerusalem by way of Constantinople and Beirut, perhaps as part of the wave of Jewish messianic expectation in 1840. After his baptism he stayed in Jerusalem, serving as superintendent of the London Society’s House of Industry, which provided vocational training to converts as well as potential converts. In 1859, Hershon retired to London, where he soon published Extracts from the Talmud, Being Specimens of Wit, Wisdom, and Learning, etc., of the Wise and Learned Rabbis. Twenty years later A Talmudic Miscellany appeared, which according to its subtitle contained A Thousand and One Extracts from the Talmud, the Midrashim, and the Kabbalah, and two years after that Treasures of the Talmud: Being a Series of Classified Subjects in Alphabetical Order from A to L Compiled From the Babylonian Talmud. Hershon was still working on the second volume at the time of his death in 1888.

Hershon’s continuing involvement with Jewish texts long after his conversion is far from unique. His better-known Belarusian-born contemporary Isaac Edward Salkinson (1820–1883) was baptized in London in 1849 and ordained a decade later in Glasgow as a Presbyterian minister. After serving as a missionary in Pressburg (now Bratislava) Salkinson spent his final years in Vienna, where his friends included the great Zionist writer and editor Peretz Smolenskin. Salkinson eventually won a place for himself in the annals of Hebrew literature through his pioneering translations of works by Milton and Shakespeare. His 1871 translation of Paradise Lost was later described by the Anglo-Jewish scholar Israel Abrahams as“attaining almost to absolute perfection.” Of his 1874 Othello, which appeared under the title Ithiel ha-Kushi, Smolenskin wrote, “To-day we exact our revenge from the English! They took our Bible and made it their own. We, in return, have captured their Shakespeare. Is it not a sweet revenge?”

Salkinson grew up near Shklov, “in an atmosphere,” Endelman tells us, “of traditional piety, abject poverty, and family tension.” Everything that we know of the future convert’s early life is ultimately based on a chapter in S. L. Zitron’s multivolume study of Jewish converts, of which both Yiddish and Hebrew editions appeared in 1923. Whereas the former, published in Vilna, carried the straightforward title Meshumodim, the Hebrew edition, which appeared in Warsaw, carried a more literary—and more lurid—title, which can be translated as “Behind the Curtain: Apostates, Traitors, and Deniers.” It was in Smolenskin’s Vienna home that Zitron, on the holiday of Shavuot, had his single encounter with the (by then) legendary apostate. Salkinson’s father had been a dayyan (religious judge) in Shklov who suffered from a speech defect that eventually cost him his career and led to a nervous breakdown. Of all his children, it was apparently little Isaac who suffered the most from his father’s frustrations. After the boy’s intellectual gifts became apparent during his early cheder years he was taught by his father, who would, Zitron tells us, “wake him every morning at four . . . from his sweet slumber, and haul him, in winter as well as summer, to the house of study, where they would devote uninterrupted hours to Talmud and the Tosephists.” For the slightest error Isaac’s father would “beat the young man, slap his face, and pull his ears.” Perhaps out of an abundance of biographical caution, Endelman does not relay this story, but it may help to explain why, unlike his contemporary Hershon and other learned apostates, Salkinson entirely forsook the Talmud along with Judaism. Salkinson’s abiding love was, instead, for literary Hebrew, to which he was deeply devoted. “Hebrew translation,” he wrote late in life, “seems to be the only talent given me, and it I have consecrated to the Lord.” It was, he continued, alluding to a passage in Matthew, “my alabaster box of precious ointment which I pour out in honour of my Saviour, that the fragrance of His name may fill the whole house of Israel.” Regardless of his spiritual motivations, many members of the house of Israel admired—and still admire—Salkinson’s service to the Hebrew language.

Just as Hershon’s story may be compared to that of his contemporary Salkinson, so too does it bear comparison with that of his fellow Galician Israel Zoller (1881–1956), who died in Rome as Eugenio Maria Zolli. Zoller, a native of Brody, had originally arrived in Italy to study at the Collegio Rabbinico in Florence. While pursuing his rabbinical studies he also earned a doctorate at the local university. Zoller went on to serve as chief rabbi of Trieste, replacing the great rabbinic scholar Hirsch Perez Chajes (1876–1927), who had been among his teachers in Florence.

In 1930, Zoller co-edited a volume of studies in memory of Chajes. He also began publishing scholarly articles on the New Testament and early Christianity, which in itself was not startling, as Chajes’s own dissertation had been on the Gospel of Mark. In 1938, Zoller published Il Nazareno: Studi di esegesi neotestamentaria alla luce dell’aramaico e del pensiero rabbinico, later translated into English as The Nazarene: Studies in New Testament Exegesis, which did not stand in the way of his appointment as chief rabbi of Rome in 1939.

Zoller is now remembered less on account of his scholarly accomplishments than his shocking conversion to Catholicism in early 1945, while still serving as Rome’s rabbi. In an interview with T. S. Matthews, Time magazine’s Rome correspondent, some two weeks after his baptism, Zoller, now Zolli, said, “I did not compare the Jewish religion to Catholicism and abandon one for the other.” Rather, he “slowly, almost imperceptibly became a Christian and could no longer be a Jew.” Matthews concluded that Zolli was “happy about his conversion” but “miserable about his apostasy.” Although the Encyclopedia Judaica’s entry on Zoller/Zolli chided him for having already “abandoned the community” in late 1943 and taking refuge in the Vatican well before his conversion, the New Catholic Encyclopedia stressed that this connection helped him to assist Roman Jews during the war. That encyclopedia also noted that “Zolli’s baptism . . . was clearly an ultimate result of his ardent interest” in Christianity. What is clear, in any case, is that the Italian rabbi’s conversion to Catholicism was hardly an instance of “radical assimilation,” as Endelman himself would, no doubt, readily concede, though he may under-estimate the significance of such sincere conversions in the modern period, as well as the extent to which such converts still identified with the Jewish people.

In 1956, Zolli’s posthumously published Italian introduction to the Old and New Testaments was reviewed in the Catholic Biblical Quarterly by Christian Ceroke, a Carmelite priest. Father Ceroke asserted that “the treatment of the NT is not of the same meaty quality as that of the OT,” adding (even more snidely) that “the author evidently did not possess the same degree of familiarity” with the former as with the latter. Zolli’s less than total familiarity with the New Testament may perhaps be excused, however, on the grounds that he spent his last years translating the talmudic tractate of Berakhot into Italian. It appeared, also posthumously, in 1958.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jokes and Justice

We were sitting in our apartment one evening when a Spanish philosopher dropped in ...

The Jewish Preview of Books—October 2018

A quick look at Jewish books being published this month.

Bookstore or Beis Medresh

How I learned to stop worrying and love to browse.

Karl Marx, the Jews of Jerusalem, and UNESCO

Some revolutionary quotations from Marx and the People's Republic of China.

ezuesse

There are many things vulnerable to disproof in the New Testament claims that evangelists make to Jews, but two specific refutations stand out. First of all, the Christian claim that there is only one way to salvation runs up against the Jewish Scriptures' explicit view that due to the covenant God made with Noah and his descendants, which still underlies all subsequent history, every culture and people can be expected to have godly, worthy and righteous people in it (such as Noah himself, Melchizedek, Job who was a non-Jew, the repentant Ninevites described in the Book of Jonah, Cyrus the Great, etc.), and it is due to such people in fact that those cultures survive (as Abraham's plea to God, and God's response in Gen. 18:22-32, indicate). One does not need to convert to Judaism nor any other particular religion in order to be saved, according to the mainstream Biblical and post-Biblical Jewish teachings.

The other key point to make about the Christian claim that Jesus is the messiah (though born of a Virgin Birth, and a divine man, literally the Son of God, part of the Trinity, etc., so Joseph was not his biological father), is that there is no adoption in normative Jewish law, simply as a matter of fact. This is the Jewish law that Jesus himself is quoted as declaring binding and from God at Sinai (in Matt. 23: 2-3). So since according to that same Jewish law the Davidic line passes down only in the male line, Jesus as described in the Gospels cannot possibly be the Messiah prophesied by the Prophets.