In Praise of Humility

In his biography for the Yale Jewish Lives series, Solomon: The Lure of Wisdom, Steven Weitzman observes that ultimate knowledge is ultimately perilous. Jewish tradition credits King Solomon as the author of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs. Over the ages, scores of other books were attributed to him, such as The Key of Solomon, a magical treatise from the Renaissance. In such works, Solomon unlocked arcane secrets of the universe. Some of those books were banned; even the three biblical books were considered suspect by various rabbis. For all his knowledge, he ended badly: too many wives; idolatry run amok; his kingdom in shambles, fatally divided after his death.

This morality play may offer a skeleton key to Weitzman’s subtle, eclectic, and unusual new book, The Origin of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age. He does not set out to discover the origin of the Jews, but to write an intellectual history of the inevitably imperfect attempts—linguistic, genetic, archeological—to decipher the enigma. This method enables him to be fair and balanced to a fault, taking a wide variety of thinkers and scholars seriously, and to task.

Intellectually, Weitzman is wary of origins. He acknowledges the influence of Foucault, Derrida, and other postmodernists critical of the very nature of roots as homogenous and hegemonic. He worries that certitude of one’s origins may be a recipe for exceptionalism. On the other hand, it’s only natural to be curious. Weitzman cannot resist the visceral Jewish temptation to hunt for yichus—the prestige of lineage, of antiquity. He declares his ambivalence at the outset: “I am not proposing to revive the search for origin; neither am I giving it up.”

There are those, of course, who carry the quest for yichus to extremes. Sundry Jews insist they are direct descendants of King David. Weitzman introduces us to Susan Roth, twin sister of the Israeli American actor Mike Burstyn, and founder of an outfit called Davidic Dynasty, dedicated to bringing “unity and promise” to the Jewish people. According to Roth, she is “a descendant of King David through Rashi, the Lurie family, the Baal Shem Tov and his great grandson Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, the famous Kabbalist and scholar.” Three years ago, Moment magazine quoted “a genealogical expert in the Syrian Jewish community” who proclaimed that Jerry Seinfeld, related on his mother’s side to the illustrious Dayan family of Aleppo, “is definitely a descendant of King David.” (I looked on Seinfeld’s Wikipedia page: Larry David appears 24 times, King David never.)

Weitzman is in favor of Jewish DNA research—which by now is safely distant from Nazi race science—but is duly skeptical of what he calls “genetic astrology.” At present, he writes, “[t]here is simply no way to establish a secure evidentiary chain to connect contemporary or recently living people with ancient ancestors.” Still, such claims are worth studying as examples of constructed identity. In the case of David, Jewish families adopt a useful narrative of heroic

ancestry, stretching back to the realm of myth.

At another extreme you have the contrarian Israeli historian Shlomo Sand, author of The Invention of the Jewish People (2008), a best-seller in Israel and an international sensation, translated into many languages, Arabic included. As summarized by Weitzman, Sand is out to debunk the widespread assumption that Jews are a nation. Judaism is a religion; the idea of the “Jewish People” arose in the 19th century “and became a reality only as the result of a social-engineering process initiated by Zionist leaders and intellectuals.” Most Jews do not derive from the Israelites of old, but are a motley cultural mix, often the offspring of converts, not least the controversial Khazars. For the sake of precision, Weitzman quotes Sand directly:

To promote a homogenous collective in modern times, it was necessary to provide, among other things, a long narrative suggesting a connection in time and space between the fathers and “the forefathers” of all the members of the present community . . . With the help of archaeologists, historians, and anthropologists, a variety of findings were collected. These were subjected to major cosmetic improvements carried out by essayists, journalists, and the authors of historical novels. From this surgically improved past emerged the proud and handsome portrait of the nation.

In other words, the “Jewish People” is an artificial, photoshopped fiction, designed to enable the ethnocentric Zionist project. Sand’s objective, says Weitzman, “is to uninvent the Jewish people by exposing the real history he accuses earlier historians of having suppressed.” The ultimate goal is the conversion of Israel into a secular state of all its citizens. In 2013, Sand doubled down in French, with a book-length manifesto called Comment j’ai cessé d’être juif, published in English by Verso as How I Stopped Being a Jew. He begins by crowing that many readers will consider his arguments “illegitimate” and “repugnant,” and will regard him as “an infamous traitor racked by self-hatred.” Weitzman sees this as self-aggrandizing:

Certainly, the scholarly critics do not seem particularly scandalized by the book’s thesis, just unpersuaded by it. The problem for them is that Sand seriously misrepresents the scholarship he claims to be reacting against, casting himself as a daring iconoclast for challenging positions that had never been argued by scholars to begin with or that, conversely, had long been broadly acknowledged.

Is Weitzman himself scandalized by Sand’s thesis of national self-invention? In one sense, hardly. “Sand has a point,” he says. “Zionist leaders went to great lengths to foster a sense of a unified Hebrew culture . . . and were thus compelled to recast their goals in the language of a religious tradition.” The creation and inculcation of a usable past is what nations do, and we are no different. The German-trained historian Ben-Zion Dinaburg (Dinur), author of the multi-volume Yisrael ba-gola (Israel in Exile), strove to “instill a sense of national consciousness” among the ingathered Jews, “or as he might put it, to remind them of a history they had forgotten.” As Israel’s first minister of education, Dinur introduced a history curriculum aimed at the construction of a collective identity. Weitzman notes that Sand was taught Dinur’s narrative as an Israeli schoolboy: “I cannot help but think that his strong aversion to the idea of the Jewish people comes from his own experience as a student.” He also points out that Sand himself relies on “a contested analogy of origination (invention) that simplifies the reality, and he recycles ideas that have an anti-Jewish pedigree.”

For his part, Weitzman sees merit in both “primordialist” and “constructivist” models of Jewish origin. Instinct and upbringing bind him to the grand narrative of Jewish antiquity, but academic rigor demands recognition of how that story can be manipulated and exploited. He is sensitive to political implications:

In Israel at least, the choice to be primordialist or constructivist is often tied to whether one is on the right or the left of the political spectrum, whether one embraces Zionism as integral to the State of Israel or advocates for a postnationalist conception of the state.

And not just in Israel. Still, as an academic specialist in the Hebrew Bible, Weitzman knows that “it cannot be relied on for an understanding of history,” making the point gingerly:

The story told of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in Genesis, most biblical scholars would agree, is an attempt by much later authors to explain the origin of their people: they might preserve certain kernels of genuine experience, but for the most part, many scholars believe, they do not reflect historical reality, having been composed in a much later period and projecting on to the past the experiences and perspectives of much later authors.

Weitzman also analyzes anti-Jewish, “counter-origin” narratives that “seek to mock and discredit the Jews by negating their own understanding of their origin.” In the Hellenistic era, when Jews again lived in Egypt, Greek writers contended that the Hebrew slaves of the Exodus were actually lepers, expelled by the pharaoh for the public good; this charge was repeated by the Roman historian Tacitus.

Weitzman devotes special attention to the 19th-century German Bible scholar Julius Wellhausen, whose “Documentary Hypothesis” remains the foundation of academic biblical studies. Wellhausen’s reading of the sources J, E, P, and D led him to conclude that Israelite Judaism, following the Babylonian Exile, had degenerated from a “nature-based” religion, “originating from the rhythms of agricultural life,” into “artificial” Pharisaic legalism. Post-exilic Jews, exposed to the cultures of Babylon and Persia, had become more cosmopolitan, but “overintellectualized their tradition, focusing on a knowledge of the law to the exclusion of emotion and spontaneity.” This line of thinking, Weitzman notes, invited invidious comparison between Jews and Aryans, furnishing fertile soil for anti-Semitism.

The Origin of the Jews is a jewel box of erudition, cushioned with misgivings. The familiar identification of the ancient Hebrews with the Habiru people of the Amarna Letters (14th century B.C.E.) turns out to be troublesome. The term “Habiru” apparently referred to nomadic brigands and rebels, and plays into the unsettling stereotype of the Wandering Jew. More appealing is the thesis of Shaye Cohen in The Beginnings of Jewishness that the classic opposition of “Hebraism” and “Hellenism” should be revised in favor of a theory of hybridity. The very word “Judaism,” first appearing in the 2nd century B.C.E., exemplifies the “fusion of Judean and Greek culture”: Yehuda plus ismos. “Jewishness,” writes Weitzman, “morphed in this period from an ‘ascribed’ status, a fixed status assigned at birth, to an ‘achieved status.’” The Hasmoneans adopted the Greek idea that religious identity could be acquired through an educational process. Archeologists have dated the first mikvah and tefillin, ritual practices that parallel Greek baths and amulets, as belonging to the Hellenistic period.

That sounds plausible to me, but Weitzman has his doubts. Does Shaye Cohen posit too sharp a break between Hellenistic Jewishness and the forms of Jewish and Israelite identity that came before? Is hybridity as understood by Homi Bhabha passé, and is the more complex “rhizomatic hybridity” a preferable model? Was modern Jewish scholarly fixation on the Greek educational ethos of paideia colored by unrequited admiration for the German ideal of Bildung, as in the case of the eminent historian Elias Bickerman? Readers comfortable with such references will greatly enjoy Weitzman’s byways, even if they lead nowhere.

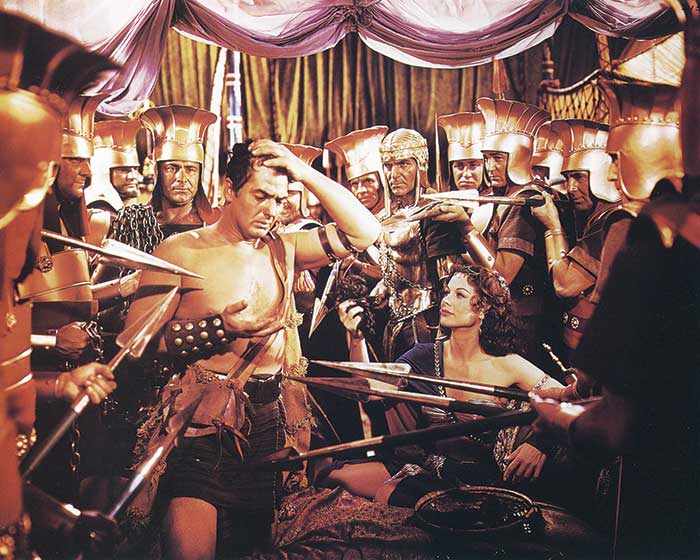

The thirst for origins is often thwarted by archeology. In Solomon: The Lure of Wisdom, Weitzman writes: “Today, when not one single find can still be confidently attributed to the Solomonic era, it is no longer clear that there even was such an era.” In discussing archeology, Weitzman focuses on Tel Beth Shemesh, the excavation near the Israeli city of Beit Shemesh. Motorists on nearby Route 38 whiz past Shimshon Junction, the turn-off to the reputed grave of Samson and his father Manoach. This is the borderland where Israelites and Philistines clashed at the time of the Bible. David slew Goliath not far from here, or so the story goes.

Tel Beth Shemesh, says Weitzman, is not famous like Megiddo or Lachish (not to mention Jerusalem), but it’s an excellent laboratory of “ethnogenesis,” a place to discover how a people began. First he tells us much about early excavators (Duncan Mackenzie of Scotland, the American Elihu Grant), their goals and biases, and where they went wrong. Weitzman loves theory, and runs on about cutting-edge “postprocessual archaeology,” as influenced by the synchronic method of one of his heroes, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. The current archeologists at Tel Beth Shemesh, Zvi Lederman and Shlomo Bunimovitz, have arrived at “a new answer to the question of Israelite origin . . . an answer that makes sense now.”

Ethnogenesis, according to this view, is a form of self-defense, a way for the people of a region imperiled by an external enemy to strengthen itself by pulling together what had been a heterogeneous population under the banner of a single cohesive identity.

Thus the Canaanites of Beth Shemesh became Israelites because of the incursion of the Sea Peoples, specifically the Philistines who settled the southern coast of Palestine and founded Ashdod, Ashkelon, and Gaza. These Canaanites, deduced Bunimovitz and Lederman, created an “invisible social barrier” between themselves and the Philistines. They accentuated their differences by means of certain practices, possibly including circumcision and certainly, on the strength of archeological evidence, a food taboo: Virtually no pig bones were found at Beth Shemesh.

The people of Beth Shemesh chose to shun a kind of food that the Philistines loved to eat, a taboo that would have probably impeded other forms of interaction between the two peoples since feasting together was such an important way for strangers to get to know each other in ancient Mediterranean culture.

In other words, it could lead to mixed dancing or worse: Just ask Samson, shorn and blinded.

Finally, we have a thesis that ties the whole room together, like the Dude’s shag rug in The Big Lebowski, that classic of postmodern epistemology. But Weitzman abides by never having all the answers. “It is important to acknowledge that this theory is vulnerable to its own share of criticisms,” he adds. “There is no way to fully reconstruct the process of identity formation that may have been at work in early Iron Age Beth Shemesh because such a process unfolded internally, within the minds of the Israelites.” And besides, too much hinges on pig bones.

Readers will come away disappointed, and Weitzman knows it. His final chapter is an extended aria of frustration:

Scholarship has produced many accounts of the origin of the Jews; some can be shown to be false; others stretch beyond what can actually be known; all are uncertain and subject to debate, and there seems to be no way beyond this impasse . . . Indeed, it seems to me that the more scholars have learned, the more difficult it has become to reach any kind of conclusion . . . Our quest has taught us that if the origin of the Jews has eluded us, it is not because that origin is remote, invisible, or hard to access, or happens not to have left a trace of itself. It is because the idea of origin is inherently difficult to pin down.

In truth, Weitzman says, the possibility of finding a clear-cut answer “was probably lost from the moment people began to question the Genesis account many centuries ago . . . [T]his is not a conclusion likely to satisfy those who opened this book expecting to learn how the Jews originated.” But then again, “I think something significant would be lost if scholars ever completely gave up.”

I confess to still nursing the hope that, despite all the dead-ends we have come up against in this book, scholars will find ways to keep asking how the Jews originated. This is not because I expect them to ever break through to a definitive answer but because I value the humility that comes from recognizing that we do not know that answer and because at the same time, I would lament the loss of a certain kind of ambition that modern-day scholarship has inherited from the myth-makers of old, the dream of being able to solve the enigma of beginnings.

So gracefully ends this unique, rewarding book. But I closed it wanting more. As a citizen of Jerusalem, I have a special stake in Jewish origins. This is no ordinary city, where you fight traffic and eat pizza and wait in long lines—this is sela kiyyumenu, “the Bedrock of Our Existence.” As I pondered Weitzman’s confession, I thought: What better time than Sukkot for a Jew to visit the City of David?

I walked from my house in the German Colony to the Old Train Station, where Theodor Herzl arrived in 1898. I took the free shuttle bus to the Dung Gate, near the Western Wall, and made my way down to the Visitor Center of the City of David. Strolling amid groups of tourists, I saw the remains of stone structures that archeologist Eilat Mazar controversially attributes to David and Solomon. The ongoing dig is designed to bolster the Jewish narrative. I read the official signs, each one featuring verses from the Hebrew Bible: “So David slept with his fathers, and he was buried in the City of David” (1 Kings 2:10, a line I chanted at my bar mitzvah). The sign explained the holes in the nearby rock:

Many generations of ancient Jerusalem’s residents were familiar with the Tombs of the House of David that were situated inside the city . . . In the generations following the destruction of the Second Temple, the tombs were demolished and their location was forgotten . . . In 1913, Baron Edmond de Rothschild purchased large tracts of land in the City of David and commissioned French-Jewish archaeologist Raymond Weill to conduct excavations here. Weill discovered several tunnels carved into the rock and identified them as the Tombs of the House of David. Weill’s theory was accepted for many years, but subsequent discoveries of lavish tombs in Jerusalem cast doubt on this.

Theories come, theories go. The City of David sits south of the Old City walls, in the midst of the village of Silwan, today a neighborhood within the unified city. The name derives from the ancient Shiloah or Siloam. Some 400 Jews have settled in Silwan in recent decades, amid about 40,000 Arab residents. On this bright October morning, blue and white flags flew as Israeli families celebrated the holiday in their Silwan sukkahs. Long ago, Jewish pilgrims presumably purified themselves in the Pool of Siloam before ascending to the Temple Mount on Sukkot and other festivals.

Who was here first? As Weitzman wrote in Solomon: The Lure of Wisdom: “Solomon’s story warns against trying to know more about the Bible than it wants to reveal.” And I wondered: Do exaggerations of Jewish origin undermine our credibility, imperil our genuine claims? Is this the cautionary subtext of Weitzman’s idiosyncratic new book? I was suddenly reminded of something I’d read in the New York Times years ago, and when I got home I looked it up.

Entitled “Israel’s Y2K Problem,” it ran in the Sunday magazine of October 3, 1999. The writer was the clever Jeffrey Goldberg, now editor of the Atlantic. Goldberg weighed the prospects of apocalyptic conflict at the coming turn of the millennium, interviewing Jewish zealots, Muslim clergy, evangelical Christians, and Faisal Husseini, once regarded as heir apparent to Arafat. Husseini’s exchange with Goldberg was what had stuck in my mind:

“First of all, I am a Palestinian. I am a descendant of the Jebusites, the ones who came before King David. This was one of the most important Jebusite cities in the area.”

Huh?

“Yes, it’s true. We are the descendants of the Jebusites.”

I decided not to slip farther down this slope; after all, there’s no arguing with a Jebusite.

We Jerusalemites share the slopes of our city with strangers. Arguments, as ever, are unavoidable, but as the author of Proverbs wrote, “with humility comes wisdom.” Respecting the unknowable origins of others alongside our own might help pave a Solomonic road to a rosier future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Weaver

An-sky's photographs.

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

Sacrificial Speech

Just a few years after the publication of her Purity, Body, and Self in Early Rabbinic Literature, Mira Balberg has somehow managed to write another path-breaking work on another formidable and arcane section of rabbinic literature—sacrificial law.

The Blessings of Manasia

His father recited Modeh Ani every morning and ordered a set of tefillin from Mumbai. Unaware that they were meant to be worn and not merely kept, he put them away on a shelf.

dcpollack

Beautiful review of an excellent book ... and to top it off, a quote from the Big Lebowski. What more could a reader ask for? רב תודות

gershon hepner

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE JEWS

The Bible seems more confident about beginnings of the universe,

starting with the word bereishit, “when in the bang beginning,” while it's introducing

a description of how earth and heaven started, but there is no verse

which uses that word to explain how Jews got started. From this I'm deducing

that the Bible claims the universe began in one brief moment----called big bang

long after the beginning of the Bible!--per contra never telling us that Jews began

with one beginning, since there were so many before Babylon.

If of my Bible-based interpretation of Jews' origins you are no fan

I'll not protest, since Jews are a phenomenal phenomenon.

[email protected]