Lost Music

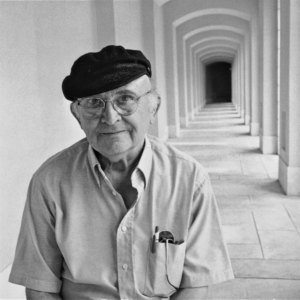

I just returned from Aharon Appelfeld’s funeral in Jerusalem. The eulogies were moving and intelligent, but the funeral was not a major public event. Although Appelfeld was much admired and highly respected, he never made himself into a public figure like other major Israeli novelists, and he never aspired to address a mass readership.

Several of Aharon Appelfeld’s characters are failed writers, men who never manage to write what they want to write or have their work published. Appelfeld was very far from a failed writer. He was published widely, in many languages. He won important literary prizes, including the Israel Prize for Literature, and his work has been the subject of scholarly books and international conferences. Yet I’m not sure that, in his own eyes, he was a success, that he ever felt he had written exactly what he wanted to write. Perhaps this helps explain his drive, his prolific creativity, his constant effort to recreate, through memory and imagination, the destroyed Jewish life of the region that was once the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Aharon had a religious belief in the power of literature and a strong conviction of his own importance—not in an egotistical way, but because he was committed to a project that he alone, he felt, was capable of accomplishing. He took upon himself the mission of conveying the meaning of his own tragedy to the Israeli public, to the Jewish people, and to all humanity, and he did so not by writing about himself but by portraying other characters whose loss was irreparable yet redeemable through art.

Many of Aharon’s characters are assimilated Jews of his parents’ generation who are unable to draw upon their Jewish roots but also unable to live comfortably in the Gentile world. Ironically (and Aharon was a master of irony), these people are often linked to their Judaism by Gentile women, servants in Jewish homes who have imbibed Jewish values. For Aharon, Jewish values are synonymous with human values. The only thoroughly Jewish characters in his fictional world are those of his grandparents’ generation, the pious parents of the confused assimilated Jews, observant old people living in villages high in the Carpathians, surrounded by forests, close to God and to nature, at peace with their Gentile neighbors, and silent. These mountain Jews no longer exist, and only through Aharon’s visions of them can we know them.

Visions are a major element in Aharon’s writings. His characters see and hear their dead parents and relatives. Their waking dreams are often a more significant part of their lives than their experiences in the material world. They are people who have never stopped sleeping.

Aharon was not a realistic writer. His novels are like dreams. He often added the words, “for some reason,” when describing his characters’ actions. I once asked him why, and he asked me, “Do you know why you do what you do?” This inability to understand is central to Aharon’s fiction. Many of his important characters are people of limited intelligence, who cannot articulate what’s happening to them, and who have no sophisticated ideas about life.

I worked with Aharon as a translator for more than 30 years. My first translation, To the Land of the Cattails, appeared in 1987. The Man Who Never Stopped Sleeping appeared only last year, and another translation of mine, Long Summer Nights, is due to appear soon. I spent long and pleasurable hours in his company as he tried to teach me how to translate him. His style is deceptively simple, and one must read him very closely to avoid overlooking its special flavor. He wrote short sentences and avoided unusual words. His Hebrew almost never resonates with biblical or rabbinical overtones. The only way in which his style might be called biblical is in its sparseness. He scrupulously avoided writing superfluous words.

It was a privilege to work with a literary genius of Aharon’s stature. If my translations have a defect (and how could they not?) it would be my excessive respect for the original. Often, to convey his meaning to me, Aharon would recite sentences to me in a kind of chant, challenging me to create music of the same kind in English. Usually it would be the opening paragraphs of his books, like the first sentences in Katerina, which are repeated almost word for word at the end of the book:

My name is Katerina, and I will soon be eighty years old. After Easter I returned to my native village and to my father’s farm, small and dilapidated, with no building left intact except this hut where I’m living. But it has one single window, open wide, and it allows in the breadth of the world.

By “music” I mean the flow of the words, the phrasing, the differences in the length of the phrases, and the way short phrases like “small and dilapidated” and “open wide” change the rhythm of the sentences. I never tried to duplicate the specific phrasing of his writing, but I always heard the words resonate in my ears as I translated. The speakers at his funeral all emphasized the musical quality of his writing. Indeed, Aharon began his writing career as a poet, and some of his paragraphs could be laid out typographically as poems.

He was a devoted husband and father, a man who lived in contemporary Israel, who traveled to Europe and the United States, and who had political opinions, none of which appear directly in his work. Shallow critics reproached him for that. He dismissed such criticism with impatient annoyance and continued to write exactly the way he wanted to write. As he said to me more than once, people who want literature to be journalism simply don’t understand what literature is.

Although Aharon was almost 86 years old, I never expected him to die so soon. I was sure he would continue writing for at least another decade, though he was very frail in the last months of his life. His widow, Yehudit, told me that his drawers are full of manuscripts that he didn’t manage to revise before submitting them for publication. Death will not silence Aharon Appelfeld, though his voice will sound different now that he can no longer chant his sentences out loud.

Suggested Reading

The Closing of the American Mind Now

Thirty years ago, a book was published that hit, in the words of the New York Times, “with the approximate force and effect of what electric shock-therapy must be like.” How has it held up? And what does that have to do with the Bible?

Learning Yiddish After 60

When I was about 10, I had a brilliant idea. If my parents would agree to speak only Yiddish with each other, it would just come to me without effort. I wouldn't have to learn it or study it, I would just wake up one day knowing it.

Awe and Joy

S. Y. Agnon curated a stunning anthology of Jewish texts, published later in English as Days of Awe. In his introduction to the anthology, the eminent scholar Judah Goldin grappled with the idea of awe—and so does this author.

Persian Daughters of Israel

Leah Sarna imagines Jewish and Gentile women doing their laundry on the banks of the Tigris, sharing tricks for keeping their headscarves tied and their bedrooms pure. She reviews Shai Secunda’s new book on just how Babylonian the Babylonian Talmud was.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In