Child of Occupation

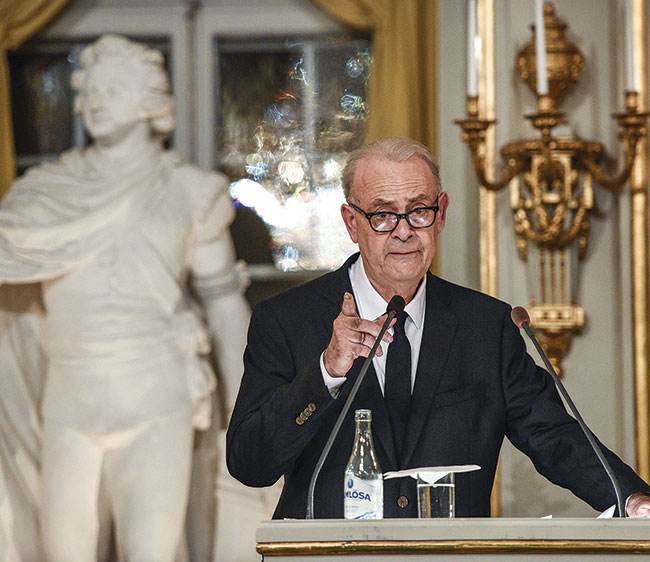

When the French novelist Patrick Modiano was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014, he was invested “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation.” Born in Paris on July 30, 1945—two months after the Second World War ended in Europe and a little under a year after the French capital was liberated—the author of uncomfortable, penetrating novellas such as La Place de l’Étoile, The Night Watch, and Dora Bruder has dedicated a good part of his literary life to inhabiting the French experience of Nazi German occupation and themes of collaboration and resistance.

“Like everyone else born in 1945, I was a child of the war and more precisely, because I was born in Paris, a child who owed his birth to the Paris of the occupation,” Modiano remarked in his Nobel lecture. Those who lived through the occupation fought to forget it, such that “when their children asked them questions about that period and that Paris, their answers were evasive. Or else they remained silent as if they wanted to rub out those dark years from their memory and keep something hidden from us. But faced with the silence of our parents we worked it all out as if we had lived it ourselves.”

As a novelist Modiano is somewhere between a provocateur and a detective, working the war years out for himself. The often-wild prose style of his earliest novellas, La Place de l’Étoile and The Night Watch, certainly feels like an effort to needle the French reading public, published as they were in the late 1960s. Consider not only that France was undergoing a period of political and social tumult but that the country was very much fortified behind its national myth of mass resistance. As Tony Judt wrote in Postwar, the notion of French responsibility for Jewish suffering simply wasn’t part of the national conversation at the time.

Modiano’s debut protagonist in La Place de l’Étoile, Raphäel Schlemilovitch (literally the son of a schlemiel), is the most unreliable of unreliable narrators, whose hallucinogenic ramblings often parody the ways in which Jews were portrayed in prewar anti-Semitic French literature. “I resolve to become a Jewish collaborator,” he says at one point. “I am the only Jew, the ‘good Jew’ of the Collaborationist movement.” Every anti-Semite, Schlemilovitch ponders, has a “good Jew.” He even gives advice to the author of an anti-Semitic column. “I’ve always thought that goys are like bulls in a china shop when it comes to understanding Jews,” he says. “Even their anti-Semitism is cack-handed.”

In a Rothian scene, Schlemilovitch reveals himself to have been the lover of Eva Braun since 1935. “I am skulking around the Berghof when I meet Eva for the first time. The instant attraction is mutual.” Hitler, we learn, has gracefully accepted Schlemilovitch’s position as Braun’s consort. “In the evenings, he tells us about his plans. We listen, like two children.” Schlemilovitch has even been given the position of honorary SS Brigadeführer. “I should dig out the photo on which Eva wrote, ‘Für mein kleiner Jude, mein gelibter Schlemilovitch—Seine Eva.’” I am, he says, the official Jew of the Third Reich. La Place de l’Étoile, whose title is taken from the traffic circle or star at the Arc de Triomphe, but also bitterly evokes the star Jews were made to wear in occupied France, forced French readers to confront their own anti-Semitism.

In his early novellas, Modiano was a sensationalist, excoriating his readers. He was especially adept at parroting the sneering anti-Semitism prevalent in polite society. The assorted characters of Ring Roads, who ride out the war in bacchanalian splendor, complain about those “bastards” who are able to live it up, supposedly, on the south coast of France. “I’ve just come back from Nice,” one of them remarks. “Not a single human face. Nothing but Blochs and Hirschfelds. It makes you sick . . .” Another explains the rules of a game he calls Jewish tennis. From what the narrator is able to gather:

[I]t was a game for two players and could be played while strolling, or sitting outside a cafe. The first to spot a Jew, called out. Fifteen love. If his opponent should spot one, the score was fifteen-all. And so on. The winner was the one who notched up the most Jews. Points were calculated as they were in tennis. Nothing like it . . . for sharpening the reflexes of the French.

“Believe it or not,” he added dreamily, “I don’t even need to see THEIR faces. I can recognize THEM from behind! I swear!”

But hidden in those explosive novellas is a desire for answers, a quest for understanding, perhaps even a search for identity, all of which becomes clearer as his writing matures and his methodical qualities rise to the surface.

The impetus for Modiano’s 1997 novella Dora Bruder came when he was perusing an old copy of the periodical Paris-soir from December 31, 1941 and saw a notice for a missing girl. It contained her name and age (15), a description including of her dress (maroon pullover, navy-blue skirt), and an address in Paris. The book is his attempt to reconstruct this little girl lost.

Over the course of his investigation, Modiano discovered that Dora was rounded up in June 1942, moved to Drancy transit camp in August, and then deported to Auschwitz in September to be murdered. “Ever since,” Modiano writes, “the Paris wherein I have tried to retrace her steps has remained . . . silent and deserted . . . I walk through empty streets. . . . I think of her in spite of myself, sensing an echo of her presence in this neighborhood or that.” Dora Bruder is a truly brilliant novella. It possesses an emotional clarity that simply isn’t present in his earliest work.

La Place de l’Étoile and The Night Watch vibrate with youthful urgency; they read like wretched, sweaty fever dreams. By the time Modiano published his third novella, Ring Roads, in 1972, the heat had come off his prose. These three works were recently retranslated and published as The Occupation Trilogy. In his preface to the volume, the Scottish novelist William Boyd observes Modiano’s “noticeably shorter sentences” and the “clipped objectivity” in his novella about a son’s search for his missing Jewish father, who has attempted to dissolve into a community of debauched internal exiles:

We should get away from this place as quickly as possible. But where would we go? People like you and me are likely to be arrested on any street corner. Not a day goes by without police round-ups at train stations, cinemas and restaurants. Above all, avoid public places. Paris is like a great dark forest, filled with traps. We grope our way blindly.

Modiano’s narrator protests that he is writing, not because it is of interest to him, but because if he didn’t do it, no one else would. “It is my duty, since I knew them,” he says of the characters in Ring Roads, “to drag them—if only for an instant—from the darkness. It is a duty, but for me it is also a necessary thing.” He focuses on misfits, on outsiders, “so that, through them, I can catch the fleeting image of my father. About him, I know almost nothing. But I will think something up.”

“I will not trouble you with my own personal story, but I do think that certain episodes from my childhood planted the seed that would become my books later on,” Modiano said in his Nobel lecture. Indeed, the keys to unlocking Modiano are to be found between the covers of his memoir, Pedigree.

I was born . . . to a Jewish man and a Flemish woman who had met in Paris under the Occupation. I write “Jewish” without really knowing what the word meant to my father, and because at the time it was what appeared on the identity papers. Periods of great turbulence often lead to rash encounters, with the result that I’ve never felt like a legitimate son, much less an heir.

The pedigree of the book’s title refers to Modiano’s feelings of social inadequacy. “My mother and father didn’t belong to any particular milieu. So aimless were they, so unsettled, that I am straining to find a few markers, a few beacons in this quicksand, as one might attempt to fill in with half-smudged letters a census form or administrative questionnaire.”

In constructing his memoir, in bringing his parents back to life, Modiano blurs the distinction between his novellas and autobiography. As in Dora Bruder, he comes across not so much as an auto-biographer but as a reporter, a historian, perhaps even a coroner. He builds his story, his case, forensically and deliberately, even dispassionately, out of the little evidence he has. Pedigree overflows with names of friends, family members, and associates that substitute for documents, memories, and heirlooms. No space is given to reflection or contemplation. Details are provided but not in order to elicit emotions, sympathetic or otherwise.

Indeed, the key moment of Modiano’s childhood is the one he devotes the least time to in Pedigree. “In February 1957, I lost my brother,” he recounts matter-of-factly. His father and uncle had come to collect him from boarding school, and, on the road to Paris, “[i]n the car, my father told me that my brother had died. . . . I will never forget the look on his face, that Sunday.” Apart from the death of his brother, “I don’t believe that anything I’ll relate here truly matters to me.” Many of Modiano’s books are dedicated For Rudy.

In the end, Modiano’s style and methods create a certain distance between the author and his life, as if he were writing about a childhood not quite his own, giving Pedigree a haunting objectivity. As he describes it, “I lived through the events I’m recounting . . . as if against a transparency—like in a cinematic process shot, when landscapes slide by in the background while the actors stand in place on a soundstage.”

His mother, Louisa, was an actress from Antwerp, Belgium. Throughout his childhood, she toured, and her absence marked the young Modiano. “I can’t recall a single act of genuine warmth or protectiveness from her,” he recalls. “Her sudden flares of temper upset me deeply, and since I went to catechism, I prayed for God to forgive her.” When the work dried up, she was destitute, reduced to petty theft. Modiano remembers having to ask his father for money on his mother’s behalf. “On certain days, I brought nothing home, which provoked furious outbursts from her.”

[N]othing softened the coldness and hostility she had always shown me. I was never able to confide in her or ask her for help of any kind. Sometimes, like a mutt with no pedigree that has too often been left on its own, I feel the childish urge to set down in black and white just what she put me through, with her insensitivity and heartlessness. I keep it to myself. And I forgive her.

It is Modiano’s father, however, who haunts his work. Born in Paris, Patrick’s father, Albert, was originally from Thessaloniki and belonged to a Jewish family from Tuscany, although relatives were scattered to points that ranged between London and Alexandria, Milan and Budapest. “Four of my father’s cousins . . . would be murdered by the SS in Italy, in Arona, on Lake Maggiore, in September 1943,” Modiano notes.

During the war, his father did not register with the authorities as a Jew. The police picked him up once in February 1942 and on another occasion in the winter of 1943, when he was denounced by someone close to him, but he somehow managed to survive. He earned a living in the black-market world of grift and barter. His parents, Modiano writes, were “two lost, heedless butterflies in the midst of an indifferent city.” The underworld in which they resided was “the soil—or the dung—from which I emerged.”

After the war, Albert would move around a lot: Canada, Guyana, Equatorial Africa, and Colombia, “searching for El Dorado, in vain.” His son remained in France, living the life of an unwanted boarding-school child. “I wonder,” Modiano writes, “whether he wasn’t also trying to flee the Occupation years. He never told me what he had felt, deep inside, in Paris during that period. Fear? The strange sensation of being hunted simply because someone had classified him as a specific type of prey, when he himself didn’t really know what he was?”

When he was 13, Modiano and his father went to see a documentary on the Nuremberg trials, the first time Modiano saw images of the extermination camps. “Something changed for me that day. And what did my father think? We never talked about it, not even as we left the cinema.” Throughout his career, Modiano has tried to understand—or at least depict and realize—people like his father. They are Modiano’s Thénardiers, beggars at the feast in occupied Paris, getting by however they can, regardless of the moral implications of their actions. Modiano’s father broke off contact with him in 1966, when he was 21, just two years before he published La Place de l’Étoile.

In one of the hallucinations that make up La Place de l’Étoile, Schlemilovitch becomes part of the “white slave trade.” Those who collaborate with the police and Gestapo in The Night Watch also have an air of debauchery about them. They reside on one of the “small islands in Paris where people tried to ignore ‘the disaster lately occurred,’ where a pre-war hedonism and frivolity festered.”

The Night Watch’s protagonist is torn between his work with the Gestapo and the Resistance, the life of a double or even triple agent. “My bosses were utterly disreputable . . . I had to provide for maman, who had little enough to live on. . . . You might think I have no principles. I started out as a pure and innocent soul. But innocence gets lost along the way.” He describes himself as “a straw in the wind” who committed wrongs whether “through cowardice or inadvertence.” He is somewhat conscious of his moral failings. “I looked at my reflection and saw the face of Philippe Pétain,” the head of the collaborationist Vichy

government.

Cowards, apparently, always die a shameful death. The doctor used to tell me that when he is about to die, a man becomes a music box playing the melody that best describes his life, his character, his aspirations. . . . When your turn comes, mon petit, it will be the clang of a can clattering in the darkness across a patch of waste ground.

Paris during the years of occupation was a strange place, as Modiano remarked in his Nobel lecture. Superficially, life continued as it had before. Theater and cinema attendances were in fact much higher during the occupation than before it. But it was also a silent city, where people disappeared and nothing was ever spelled out or made clear. It was like living in a bad dream. “That is why for me, the Paris of the occupation was always a kind of primordial darkness,” Modiano said. “Without it I would never have been born. That Paris never stopped haunting me, and my books are sometimes bathed in its veiled light.”

Modiano is fastidious and obsessive as he summons up Paris in the pages of his novellas. On one page of The Night Watch, the reader approaches an “avenue lined with glittering street lights” that looks like a vision from the future, full of promise, only to discover it is the Champs-Élysées with its “cosmopolitan bars” and “call girls.” There is the “bleak sadness of the Lido,” the sleaziness of the Madeleine-Opéra district, the arcades of the Rue de Rivoli.

Few have written about France’s capital as well as Modiano. His Paris is filthy, dirty, gritty, alive, and multitudinous. As deft as he is with the details—the smells, sights, and sounds—he is also adept at conveying its atmosphere, as in this passage from Ring Roads:

Have you noticed, Baron, how quiet Paris is tonight? We glide along the empty boulevards. The trees shiver, their branches forming a protective vault above our heads. Here and there a lighted window. The owners have fled and have forgotten to turn off the lights. Later, I’ll walk through this city and it will seem as empty to me as it does today. I will lose myself in the maze of streets, searching for your shadow. Until I become one with it.

Modiano began as a slaughterer of sacred cows in the raucous La Place de l’Étoile, but in the novels that followed, he employed memory and imagination to capture what the Nobel committee called “the life-world of the occupation,” where suffering occurred underneath the banality of the everyday life, while collaborators resided in a kind of suspended opulence, built upon the misfortune of others.

Suggested Reading

How the Baby Got Its Philtrum

The idea of learning as a recovery of what we once possessed is what makes Bogart’s bubbe mayse, and ours, so memorable: We can all touch that little hollow and feel the impress of forgotten knowledge.

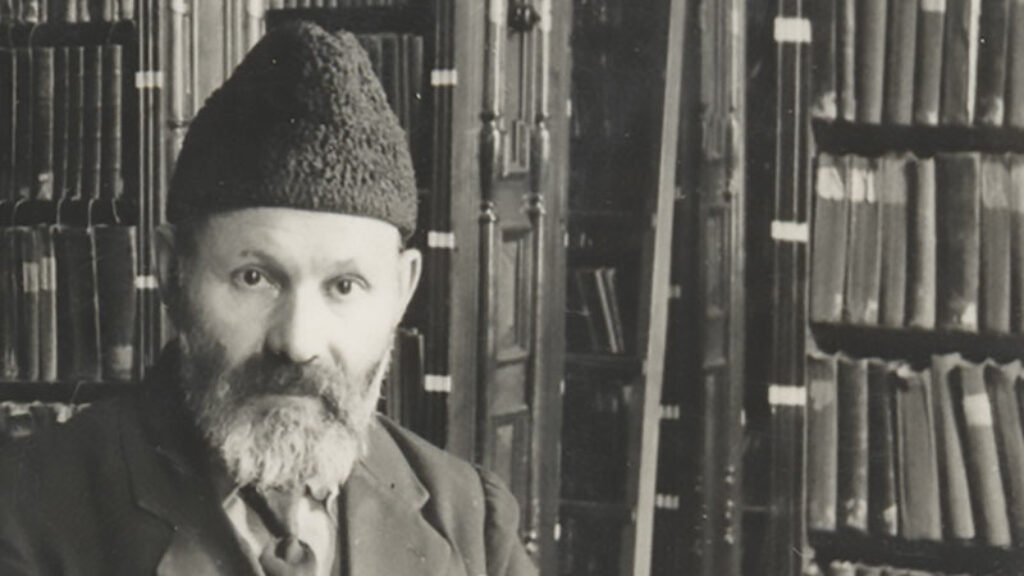

Golden Books

Three decades ago, Allan Nadler went to Vilna to reclaim books that the Nazis had plundered from YIVO, or so he thought. Dan Rabinowitz’s Lost Library solves the mystery—and raises important questions.

Rachel and Her Children

Eternal Life is Dara Horn’s fifth novel, and like her others it crosses time and place to tell a transfixing, multilayered story that draws on Jewish texts and themes in a deep, witty, and immensely readable fashion.

Raising the Asmonean Banner

Two teenaged sisters wrote surprisingly sophisticated and moving poetry about the Maccabees and a medieval massacre.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In