Telling the Whole Truth: Albert Memmi

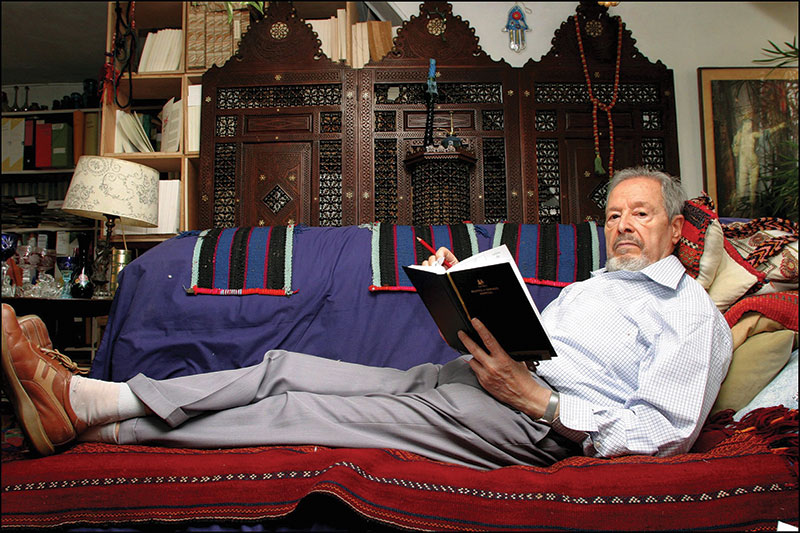

“I continue to think, in spite of frequent hesitations, that I must tell not only the truth but the whole truth. And this will be not only my aesthetic signature . . . but my most important political contribution.” With this diary entry from 1956, the young Tunisian writer Albert Memmi summed up the attitude that has earned him both admiration and enmity over an intellectual career that has spanned more than half a century.

Memmi has defended Third World revolutions while condemning their tyrannical by-products ever since his native country drove out its Jewish population soon after attaining independence. The recently published Tunisie, An I (Tunisia, Year I) is Memmi’s diary from the years 1955 and 1956. This was when Tunisia ceased to be a French protectorate and became, as its new constitution stated, “an Islamic state.”

Born in 1920 and still active, Memmi grew up on the border of Hara, the Jewish ghetto of Tunis, and an adjacent Muslim neighborhood. His family spoke Judeo-Arabic at home, but he became a scholarship student at the best French schools. In the early 1950s, he emerged as a prize-winning French novelist, then turned his hand to political theory. In 1957, his most widely read and translated work, The Colonizer and the Colonized, appeared with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre. Memmi’s book, with its far-reaching conceptions of colonial privilege and racism, was essential reading in radical theory until the 1970s, when he began to fall from grace in leftist circles, partly because of his defense of Israel, partly because of his criticism of the new Muslim nations of North Africa and the Middle East.

The seeds of Memmi’s separation from the Left are already evident in some of the diary entries in Tunisie, An I. Guy Dugas, a professor at the Paul Valéry University in Montpellier, is to be congratulated for editing the diary, and for including several articles by Memmi from the 1950s that dealt with the pressure faced by Jews in decolonizing North Africa. In one of these articles, an essay published in 1956, Memmi argued that how a polity treats its Jews is the best index of its level of freedom. “A society that wishes to liberate humankind must naturally liberate its Jews . . . At least in our historical era, the destiny of the Jew is consubstantial with the destiny of man.”

Memmi’s startling independence of mind has always been linked to his Jewish partisanship. His sensitivity to the persecution of Jews in political regimes of all types meant that he had no a priori attachment to socialism, nationalism, capitalism, or any other “ism.” He has combined, perhaps more than any other writer since World War II, the compassion needed to articulate the suffering of oppressed groups with the forthrightness needed to censure them for their own acts of oppression. “[I]f we are to help decolonized peoples,” Memmi wrote in 2004, “we must . . . acknowledge and speak the truth to them, because we feel they are worthy of hearing it.”

In the diary, Memmi chronicled how the newly independent regime in Tunisia downgraded the status of its Jewish subjects. Jews were removed from their positions in the bureaucracy; anti-Semitic poems were broadcast through government radio stations. He recounted how the president of the new Constituent Assembly, Habib Bourguiba, summoned Jewish leaders and ordered them to stop showing support for a foreign power, Israel. The president of the Jewish community, Charles Haddad, was defiant. He asked Bourguiba this question: If allegiance to other countries is treason, why do you constantly pledge support to the Arab League? The debate was especially impressive, Memmi noted, because Haddad previously was a man of “unctuous prudence.”

Memmi showed how his fellow North African Jews came to realize that they could no longer fantasize about assimilation or acceptance in a multiethnic postcolonial society, despite the fact that many of them did not descend from European colonists. Memmi himself possessed a medallion, bearing his family name, that dated to the Punic Wars, long before the arrival of Islam in North Africa. He later donated it to Yad Vashem as evidence that Jews were as native to Tunisia as any other group. As Memmi noted in the diary, he and other progressively minded Jews initially thought they were comrades in arms with the Muslim population against colonialism. Now they had to recognize that they had enjoyed more liberty under colonialism than in the newly liberated states.

“I have to aid the Tunisians [against the French] because their cause is just,” Memmi wrote. “And I have to leave Tunisia because their cause is not mine.” He departed for France at the end of August 1956. He was not alone. The historian Michael M. Laskier observes that there 65,000 Jews in the capital of Tunisia in the late 1940s. Between 1956 and 1967, the majority immigrated to France or Israel.

In a 1962 article in Commentary magazine, Memmi wrote that “the fate of North African Jewry is the most important world Jewish problem of our postwar period, just as the fate of the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe was the leading problem for Jews before 1939.” The need for a Jewish homeland, he observed, was “not the result of Auschwitz but of the Jewish condition everywhere, including the Arab countries.”

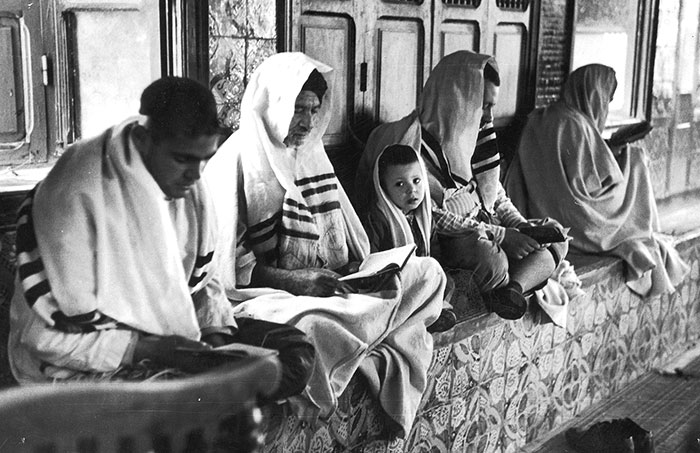

“The Jewish condition” would remain central to Memmi. In Portrait of a Jew, he coined the French word judéité (Jewishness) to describe the sentiment of belonging to a Jewish community as distinct from subscribing to the tenets of Judaism. Judéité is largely a nostalgic bond—a warm recollection of festivities celebrated at home, for example. Near the beginning of his first novel, Pillar of Salt (1953), Memmi evoked this ambiance.

Friday was always born in an excited dawn, and it blossomed majestically into a triumphant Sabbath . . . The men would then drink their little glasses of araki as they ate force-meat balls, chick-peas, and strongly seasoned pickled carrots and squash. . . . I suppose I used to fall asleep while still at table . . . Sleep, when one has no worries, tastes like honey.

Yet, judéité for Memmi is also a bitter condition imposed from outside; it is a community of fate abetted by persecution. In his preface to Pillar of Salt, Albert Camus praised the young author’s decision to identify as Jewish. “By writing about the difficulty of being a Jew, the author ultimately chooses to be one (and so much the better), replacing the traditional religious awareness of his ancestors with an awareness that is more modern, dramatic and intellectual, a solidarity without illusions.”

Memmi did not seek to displace Judaism with an allegedly higher or more universal commitment. Unlike Marxists and other internationalists, he sought to make the world a place in which Jewish people could continue to be Jewish. In his 1975 essay “What Is a Zionist?,” Memmi wrote:

The reasoning used by people on the left proceeds from that open-sesame simplification that they apply to so many problems: let’s bring about the revolution, they say, and the Jewish problem will take care of itself . . . This theory does not seem to be borne out by what we know of the U.S.S.R. and the Eastern European people’s democracies . . . The Marxists, following the example set by Marx himself, apply to the Jewish problem a pattern that is obviously irrelevant; for they persist in understanding it in terms of economics and of class struggle, whereas it is a phenomenon of an altogether different kind . . . That is why I protested so strongly when attempts were made to reduce the colonial problem first, then the Jewish problem to a matter of class struggle—in other words, when you come down to it, to an economic employers-workers problem. It is reductions such as these that have made the ideology of the political left in Europe impotent.

According to Memmi, the liberation of the Jew would not be an incidental by-product of generically framed ideals of equality and social justice. In a world of real nations, many of which had incubated hatred of the Jewish people for centuries, an explicitly national solution was needed. “This,” he wrote, “is how I came to Israel—step by step, logically, not through some transport of religious or impassioned feeling.”

The essential and undeniable fact is that from now on, the State of Israel is part of the destiny of every Jew anywhere in the world who continues to acknowledge himself as a Jew. No matter what doubts or even reproofs certain of Israel’s actions may arouse, no Jew anywhere in the world can call its existence in question without doing himself grave harm.

Pillar of Salt captured two major prizes for French literature and was quickly translated into English, Hebrew, and German. The main character in this heavily autobiographical tale is Mordekhai Benillouche, whose early years pass innocently in his “alley,” or working-class Jewish neighborhood, in Tunis.

The Jewish community provides a scholarship for Mordekhai to attend one of the best French lycées, where the rich Jewish students ridicule his ghetto accent, while the Gentile students, and some of the teachers, insult him for his conspicuous Jewishness. In spite of his isolation, or because of it, he immerses himself in the French curriculum and falls in love with European literature and philosophy. He also withdraws from the family’s Sabbath celebrations, repulsed by their “sacred triviality,” and stops accompanying his father to synagogue.

Great problems, true values, and a serious philosophy of life were elsewhere; I found them each day at school . . . Were we heading toward a Socialist society? Is poetry rooted in mysticism? Would the machine age bring social justice? Are art and morality bound together? Here were problems that were far more noble than whether one should ride a streetcar on the Sabbath.

Piercing quarrels with his father ensue. “[W]e dealt each other wounds that would never heal.”

At school, he continues to excel, and wins a prize as the best high-school student in the country. Though alienated from his family and his religion, he continues to hope that academic success will guarantee happiness. Then comes the German occupation. Thousands of Jews are conscripted into labor camps where they are forced to wear yellow stars. Since the wealthy pay a tax to the occupying power, Jews who attended elite schools are often spared. By virtue of his diploma from a prestigious school, Mordekhai is mistaken as one of them, but he refuses the exemption.

How was it possible to stay in the offices while all those young Jews were being beaten, humiliated, and killed in the camps? To the astonishment of our directors and the half-ironic surprise and respect of my colleagues, I asked to be allowed to join the camp workers. I am not trying to pride myself on my decision.

Curiously, in the camp, he leads a Torah study group—not, he claims, out of religious belief, but to raise the morale of the others. He then escapes and tries to join the Free French Forces, but discovers that Jews are not welcome. He will be accepted only if he enters a Muslim name in the registration book. At the end of the novel, he inscribes his Jewish name and walks out. Feeling that “my past has again risen like vomit in my throat,” he decides to emigrate to Argentina. Like Lot’s wife, who was turned into a pillar of salt, he will die if he looks back again.

As painful as Pillar of Salt is, it is less excruciating than Memmi’s second novel, Strangers (1955). The original French title was Agar (Hagar), the name of Abraham’s non-Jewish spouse; the novel is about the deterioration of a marriage between a Tunisian Jewish doctor (who is never named) and Marie, his French Catholic wife, whom he met while studying in Paris. (The characters bear some resemblance to Memmi and his wife, though their actual marriage endured happily.)

When the doctor returns to Tunis with Marie and takes her on a tour of the favorite sites of his youth, her only response is that she cannot bear the smell. She finds it repulsive to share the kiddush cup with his family on the Sabbath and finds the Passover Seder to be “barbaric.” As she pressures him to separate from his family and religion, he persists in dragging her “down sordid lanes, where the gutters ran with muddy water.”

I did not spare her the smells from meat stalls and rubbish heaps. I made her eat in taverns where I would never have thought of going myself.

He is torn between his judéité and his growing tendency to see his past through Marie’s disdainful eyes. The birth of a son brings more problems to the fore. In a later book, The Liberation of the Jew, Memmi wrote that in a mixed marriage “children bring to light the problems inherent in the situation . . . Suddenly all theoretical options which had been relegated to the background and left in a convenient and equivocal shadow require urgent attention.”

Memmi began writing his first work of social theory, The Colonizer and the Colonized, soon after publishing Strangers. He would later describe a connection between the two books.

I discovered that the couple [in Strangers] is not an isolated entity . . . on the contrary, the whole world is within the couple . . . I felt that to understand the failure of their undertaking, that of a mixed marriage in a colony, I first had to understand the colonizer and the colonized, perhaps the entire colonial relationship and situation.

Memmi went on to write several more works of fiction, but, with the appearance of The Colonizer and the Colonized in 1957, the novelist who wrote like a sociologist became a sociologist who wrote like a novelist.

“[T]he idea of privilege is at the heart of the colonial relationship,” Memmi wrote in The Colonizer and the Colonized. Privilege meant more than economic advantage. Memmi swept away the Marxist assumption that colonialism was primarily an economic system. What was needed was an analysis of racism that treated it as more than a buttress of economic inequality. Racism was “[a] mixture of behaviors and reflexes acquired and practiced since very early childhood, established and measured by education,” and it was “incorporated in even the most trivial acts and words.”

In spite of making claims to modernize, the colonialist never wished to raise the level of the natives. “The colonialist stresses those things which keep him separate, rather than emphasizing that which might contribute to the foundation of a joint community.”

Racism appears then, not as an incidental detail, but as a consubstantial part of colonialism. It is the highest expression of the colonial system and one of the most significant features of the colonialist. Not only does it establish a fundamental discrimination between colonizer and colonized . . . but it also lays the foundation for the immutability of this life.

For the colonizers, the need for cultural superiority even took precedence over the quest for financial profit.

Contemporary reviewers of The Colonizer and the Colonized on the left generally did not begrudge Memmi his focus on culture rather than economics, for he was still explicating the broad Marxist themes of inequality and injustice. In his preface, however, Sartre was at times critical of this incipient heresy: “[H]e sees a situation where I see a system,” Sartre wrote. Indeed, while portraying colonial racism with a broad brush, Memmi also inventoried what he called “situations” that defied class analysis. One such situation was the relatively equal and familiar rapport between Corsicans and native Muslims in North Africa. Another was the status of Jews in North Africa. The Jews often tried to assimilate to the culture of the colonizers, but the colonizers did not admit them as equals. Thus, the Jews lived in “painful and constant ambiguity.” “Rejected by the colonizer . . . they reject the values of the colonized as belonging to a decayed world from which they eventually hope to escape.”

Memmi departed from the Marxist script in one other respect: He warned of the likelihood that anticolonial revolutions would fail to produce tolerant societies. While the European left hoped that international socialism would emerge from native revolts, the reality, Memmi noted, was a renaissance of religious and ethnic self-absorption. Near the end of the book, Memmi predicted that the insurgents “will forego the use of the colonizer’s language, even if all the locks of the country turn with that key.” They “will prefer a long period of educational mistakes to the continuance of the colonizer’s school organization.” Everything that belonged to the colonizer was unfit for the colonized, after all “[t]hat is just what the colonizer always told him.” Memmi gave a name to this reproduction of rejection: He called it the “counter-mythology.”

Memmi’s cautionary remarks in The Colonizer and the Colonized were the beginning of a skeptical, heterodox strand in his work. He increasingly drew attention to the failure of colonial liberation movements to create inclusive polities. In Jews and Arabs (1975), he wrote, “unlike many people, I never believed in the liberals’ naïve assumption nor in the communists’ sly claim that after independence there would be no problems, that our countries would be lay states wherein Europeans, Jews, and Moslems would cohabit on good terms with one another.” He reproved French leftists for believing that the flight of 800,000 Jews from Arab nations was a voluntary response to the creation of Israel and not a deliberate purge.

With respect to the Palestinian refugee problem, Memmi affirmed that the Palestinians had a right to a national existence of their own. “Any leaders who do not subscribe to that interpretation at all, or who feel that it would run completely counter to Israel’s existence, must start taking much more serious steps to integrate the Palestinians [into Israeli society].” But a major component of the Palestinian problem, according to Memmi, was that the Palestinians accepted neither integration into Israel nor the creation of a Palestinian nation alongside Israel. They “think of only one thing: reconquering Israel.”

In his 2004 work Decolonization and the Decolonized, Memmi wrote that “the tree of national independence” has produced only “stunted and shriveled crops.” The new societies have not curbed violence against women; imprisonment and execution are used more frequently than they had been under colonialism; writers are more persecuted for free thinking than they had been under the colonial governments. Horrible tribal wars have broken out. Economic inequality is extreme in the Arab world, with “certain Bedouin families” possessing “fabulous wealth from lands where they arrived more or less by accident.” Political dynasties and military despots rule in place of popular government.

In a section of the book called “Diversions, Excuses, and Myths,” he wrote, “The ruler will do his best to convince his citizens that others are the cause of their problems, not his own machinations, the dysfunctional economy, administrative disorder, or their own shortcomings.” The evil is always foreign domination. “If the economy fails, it’s always the fault of the ex-colonizer, not the systematic bloodletting of the economy by the new masters, not the viscosity of their culture, which fails to address its present and the future.” Sometimes the stagnation “is attributed to a new ruse of global capitalism, or ‘neocolonialism,’ a term sufficiently vague to serve as a screen and rationale.” But in Arab countries, it is often the Jews and Israel that are blamed.

A negotiable solution to the Palestinian problem would be realistic, according to Memmi, if the problem were taken for what it is: a “minor drama” compared to “the magnitude of the problems—demographic, economic, political, social, cultural, and religious” that face the Arab world as a whole. The Palestinian problem is in fact “a rather ordinary struggle between two small emerging nations, whose national claims unfortunately turned out to involve a territorial conflict.” The Second Intifada, Memmi noted, cost two thousand lives.

That’s two thousand too many. But a quick glance at any collection of newspapers will show that, in the past few decades alone, there have been more than a million deaths in Biafra, five hundred thousand in Rwanda, uncounted massacres in Uganda and the Congo, three hundred thousand deaths in Burundi . . . the eradication of Communists in Indonesia, estimated at five hundred thousand, and the terrifying massacres of the Khmer by their own people.

If the Germans and French could make peace, Memmi said, so could Palestinians and Israelis. But “the conflict extends beyond the Palestinians and Israelis, involving nearly all the Arab-Muslim countries and the majority of the world’s Jews. The Palestinians are not as isolated as they claim; they are the foot soldiers of the Arab world, which flatters them as it leads them to the slaughter.” Israel, according to Memmi, “is not a colonial settlement, which would therefore be legitimate to destroy, an idea the Arab states have tried to promulgate.” For aside from its domination of the Palestinians, which Memmi called “unacceptable,” Israel “has none of the characteristics of such a state.”

In the English translation of Decolonization and the Decolonized, Memmi recounted how he was finally expelled from the ranks of distinguished postcolonial thinkers. Numerous interviews and reviews, scheduled before his book’s publication in French, were canceled after the work appeared in print. “[T]his weighty silence,” he wrote, “suggests . . . the accuracy of my claims. This includes my remarks about the irresponsibility, if not blindness or cowardice, of many intellectuals, who have taken refuge in outdated theories instead of daring to confront a novel situation.” One of the book’s few reviewers was an American, Lisa Lieberman, who rebuked the author in an essay entitled “Albert Memmi’s About-Face.” Memmi, she wrote, had distanced himself “not only from his radical fellow travelers, but also from his earlier self.” But, of course, Memmi’s refusal to place unconditional faith in liberationist movements had been a hallmark of his thought since the 1950s.

A few years later, during the Arab Spring, Memmi presciently commented that he observed no fundamental change taking place—only “revolts” co-opted by theocrats and not “revolutions” that would enhance the rights of women and minorities. Asked by a journalist if he was concerned about the “recrudescence” of anti-Semitism in Tunisia since the flight of President Ben Ali in January 2011, he tartly replied, “In Tunisia there is no recrudescence of anti-Semitism but rather a permanent anti-Semitism.”

The midcentury struggle against colonialism in North Africa produced major works including those of Memmi, Mouloud Feraoun, and Albert Camus. The most celebrated text, however, is Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. Born in Martinique, Fanon moved to Algeria, where he advocated violent revolution.

A psychiatrist, Fanon had profound insight into the neuroses of oppressed natives. But his single-minded purpose was to justify bloodshed. Colonialism, according to Fanon, turns the native into a “thing.” He becomes a “man” and “finds his freedom in and through violence.” Violence is not only a means of regime change; it is the very end of the process of self-transformation. Killing is, then, a kind of therapy, facilitating the rebirth of the formerly oppressed. In a preface to Fanon’s book—one that was much warmer than the one he had written for Memmi a few years earlier—Sartre validated this bloody philosophy: “The Nation marches forward; for each of her children she is to be found wherever his brothers are fighting . . . they are brothers inasmuch as each of them has killed and may at any moment have to kill again.”

Memmi demurred. In 1971, he published a penetrating essay on Fanon’s paroxysmal politics entitled “The Impossible Life of Frantz Fanon.”

When social despair is too great, men succumb to the temptation of messianism. They are gripped by a lyrical fever, by a manicheanism that constantly confuses ethical demand and reality . . . Frantz Fanon’s success is probably due more to this uncompromisingly prophetic attitude than to his particular theses or the correctness of his analysis. So that here, as in the rest of his life, it is his failure itself that has become the source of his far-reaching influence.

It was, one might say, precisely the renunciation of such brutal Manichean politics that has kept Memmi from having the kind of far-reaching influence that Fanon has enjoyed.

While Memmi never denied that violent revolt was sometimes necessary, he insisted on a distinction between the process of liberation from oppression and the achievement of durable liberty. This is, arguably, a characteristically Jewish distinction. As readers of the Bible from Moses Maimonides to Michael Walzer have noted, the book of Exodus vividly depicts the difference between the Israelites’ liberation from Egyptian bondage and their maturation as a people in the desert for 40 years. The great cultural Zionist Ahad Ha-Am summed up this tradition when he wrote that “[a] people trained for generations in the house of bondage cannot cast off in an instant the effects of that training and become truly free.” At the end of The Colonizer and the Colonized, Memmi made a parallel point about the postcolonial revolutionary: “In order that his liberation may be complete, he must free himself from those inevitable conditions of his struggle.”

Although Albert Memmi burst upon the intellectual scene as someone who had brilliantly dramatized and theorized the injustices of colonialism, his full message was one that neither violent rebels nor armchair theorists ultimately wished to hear. His work was too subtle, too unflinchingly honest, and too unabashedly Jewish for that. He began telling the “whole truth” in the 1950s, and while he is now 97 years old, one hopes that he still has more to say.

Suggested Reading

Mastering the Return

Embedding biblical allusions in her descriptions of pagan practices, Tova Reich in her new novel seems to suggest that the world is so entangled that there is no space between the sacred and profane.

Strategic Imperatives

In his new book, Charles Freilich examines the question of how future governments ought to cope with Israel's fundamental defense predicaments.

Israel’s TikTok Problem

Why has TikTok become a hotbed of anti-Israel and antisemitic content, and what does it tell us about brewing global conflicts.

A Lone Soldier

Every year, when Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s memorial day, rolls around, the author thinks of an idealistic college student named Alex Singer who became a lone soldier in the IDF.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In