Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

On March 30, 1866, a certain J. A. Joel wrote a column for page two of New York’s Jewish Messenger newspaper. It began, “The approaching feast of Passover, reminds me of an incident which, transpired in 1862.” Joel, a Cleveland resident and member of the Union army’s 23rd Regiment of Ohio, had been camped at winter quarters near the village of Fayette, West Virginia. With spring approaching and no battles looming, the 20 Jews in the regiment decided to organize for Passover.

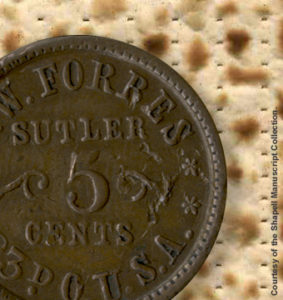

The first consideration was matza, which 19th-century Jews ordinarily procured through congregations or, in large cities, from commercial bakeries. In this case, for a regiment encamped in the wilds of West Virginia in the midst of the Civil War, the sutler (the merchant tasked with provisioning the troops), who happened to be Jewish, was quickly dispatched to Cincinnati for the necessary unleavened bread. (Already in 1849, one author claimed that over 20,000 pounds of matza were baked annually in Cincinnati.)

On the day of the first Seder, seven barrels of matza arrived, along with two haggadahs. The men went foraging for the remaining necessities. “We obtained two kegs of cider, a lamb, several chickens and some eggs.” Unsure of which part of the lamb to use, “Yankee ingenuity prevailed, and it was decided to cook the whole and put it on the table, then we could dine off it, and be sure we had the right part.” Unable to prepare haroset, a fruit-and-nut paste reminiscent of mortar, they used a brick, “which, rather hard to digest, reminded us, by looking at it, for what purpose it was intended.”

Joel read the services, beginning with prayers for the hard-won food and for the safety of the gathering. All went smoothly until they got to the bitter herbs. In the absence of horseradish or parsley, these were represented by, “a weed, whose bitterness, I apprehend, exceeded anything our forefathers ‘enjoyed.’” At this point, the Seder took a turn:

We all had a large portion of the herb ready to eat at the moment I said the blessing; each eat [sic] his portion, when horrors! what a scene ensued in our little congregation, it is impossible for my pen to describe. The herb was very bitter and very fiery like Cayenne pepper, and excited our thirst to such a degree, that we forgot the law authorizing us to drink only four cups, and the consequence was we drank up all the cider.

Then, Joel recalled, things got out of hand:

Those that drank the more freely became excited, and one thought he was Moses, another Aaron, and one had the audacity to call himself a Pharaoh. The consequence was a skirmish, with nobody hurt, only Moses, Aaron and Pharaoh, had to be carried to the camp, and there left in the arms of Morpheus.

In the midst of the bloodiest conflict in American history, after a long winter in West Virginia backcountry, this plucky group of Jews improvised a unique version of an ancient tradition, cobbling together the tastes and symbols of Passover under truly unusual circumstances. And yet, it is striking that amid the significant effort to procure all the right foods and retell the story of redemption from bondage at the heart of the holiday, the celebration’s obvious connection to the Union cause went unmentioned—at least in Joel’s recounting of that remarkable Seder. Joel described his own motivation for enlistment as “to sustain intact the Government of the United States.”

At the end of his column, as he remembered his fallen friends, Joel waxed nostalgic:

There, in the wild woods of West Virginia, away from home and friends, we consecrated and offered up to the ever-loving God of Israel our prayers and sacrifice. I doubt whether the spirits of our forefathers, had they been looking down on us, standing there with our arms by our sides ready for an attack, faithful to our God and our cause, would have imagined themselves amongst mortals, enacting this commemoration of the scene that transpired in Egypt.

I’ve read Joel’s article aloud at a number of Seders over the years, and it is always a hit. It is a story of ingenuity and patriotism, showing that even the most time-honored religious traditions are not isolated from the currents of history. Indeed, Joel wrote about a time of crisis but he also wrote during one. Though in 1866, when this column appeared, the war had been won, the difficult process of reconstruction and reconciliation was just beginning. As Joel wrote, it was also coming up on one year since Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, which had taken place during the eight days of Passover.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Apples, Honey, and Articles

A compilation of 10 favorites from the JRB archives that follow the arc of the fall holidays, from Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, to Sukkot and Simchat Torah.

Psychology at Nuremberg

Both Kelley and Gilbert believed they could make a broad psychosocial argument despite the limited sample size, inconclusive tests, infighting, and lack of clear standards and definitions.

Berdyczewski, Blasphemy, and Belief

Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, one of the towering figures of the rabbinical establishment, found deep lessons about faith in the writings of the Nietzschean heretic Micha Josef Berdyczewski.

To Spy Out the Land

A palm tree over one grave and a fence around another—two new books explore the history and legacy of the Nili spy ring.

dcpollack

מעניין. כל הכבוד. אני אקרא חלקים מאמר הזה בסדר שלי. רב תודות עוד פעם.