Biography of the Jewish Bible

In a recent issue of the Jewish Review of Books, Adam Kirsch gave an incisive review of David Stern’s new book on the material history of the Jewish Bible, the story of the Jewish scripture in its many forms, from Torah scroll to digital text. I sat down with Professor Stern to ask a few more questions about the strange and fascinating biography of Judaism’s most sacred book and the unexpected story behind his 15-year research project.

Tell us about your book’s title. Most people are familiar with the term “Hebrew Bible”; why do you use “Jewish Bible”?

“Jewish Bible” is a term I made up to refer to the physical Bible that Jews have actually held in their hands, the ones they’ve used and read. This is the subject of the book—the history of the physical shapes of the Bibles Jews have used. So you can’t really study the Bible as anything other than a material object.

How is studying the Bible as a book different from studying the text of the Bible?

The idea of the text is an abstraction—the text is only a constellation of words in your head until it is written on some sort of surface. A text doesn’t become a book until it’s inscribed, whether in a scroll or a codex, on a digital screen or a tablet (clay tablet or Apple tablet!). The book conveys the text, but the book can have meaning as an artifact—meaning that goes way beyond the text.

Can you give me an example?

We think of the Torah as a monumental scroll that includes all five books of Moses. Originally, however, the Torah was five separate smaller scrolls, one for each book, that could be held in your hand or on your lap. It wasn’t difficult to scroll back and forth. (The idea that you can’t comfortably scroll back and forth in scrolls is completely wrong. It’s just as easy as using a book.) These smaller scrolls were not much different than scrolls of texts being written throughout much of the contemporary Near Eastern world. It is not clear that these scrolls, at that time, had any specific ritual or sacred meaning beyond the fact that they were believed to be the word of God.

The classical rabbis transformed those five smaller scrolls into a single, monumental scroll that is only good for ritually chanting in the synagogue. Gradually, the Torah came to take on a special meaning; it basically became an icon for the presence of God in the synagogue: Its costuming—the crown, the breastplate, and so on—and the way it is carried around the synagogue in a special procession, taken in and out of the aron [ark] all evoke this status.

It has even, at times, been attributed supernatural, quasi-magical powers. For example, in Eastern Europe they would tie a string to the doors of the ark, run it through the town, and tie it to the bed of a woman in labor. She could then tug on the string to open the doors of the ark so that this might hasten the “opening” of her womb. None of these additional meanings that the Sefer Torah has are connected directly to the text in the Torah or what that text says.

What about the Bible as manuscript codex? After all, that’s just a book. Did it have any distinguishing features or functions?

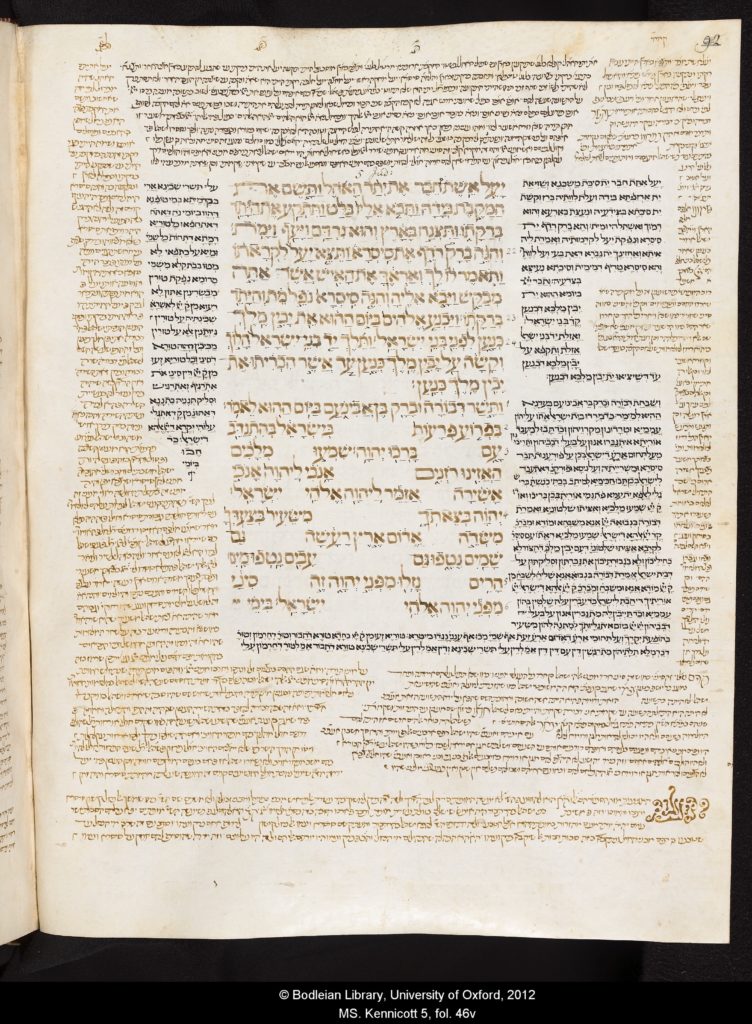

The Masorah—the corpus of notes connected to the Biblical text that first appears in the 10th century—is this enormous, almost crazy system of counting and recording every idiosyncratic feature of the text of the Hebrew Bible. For example, you’ll have an enumeration of how many times the word okhlah (eat) appears in the Bible—twice, once with a vov (in Gen 27:19), and once without it (I Sam 1:9). It’s a truly obsessive, utopian project, somewhere between book-keeping and connoisseurship. And it’s entirely Jewish. The Masorah only begins to appear on the page in Hebrew Bible codices. According to halakhah, you can’t write it in a kosher Torah scroll.

Why did Jews start taking these obsessive, statistical notes on the Biblical text?

One of the Masorah’s original purposes was to guarantee the accurate transmission of the Torah and the correct writing of the Torah scroll. (Though, of course, because compiling the Masorah was a Jewish project and Jews never agree about anything, there were competing Masorahs with different views as to what constitutes the correct Torah scroll!) But eventually, in the Middle Ages, it became a distinguishing feature of Jewish Bibles, and almost necessarily had to be on the pages of a Jewish Bible to show it was Jewish.

One thing that’s interesting is how the Masorah is presented. Jews adapted the artistic conventions of their Gentile host cultures’ books—geometric designs in Islamic lands, figurative designs in Christian lands—and rendered them in tiny micrography made of the text of the Masorah. In Ashkenaz, for example, Jews appropriated various Christian stylistic motifs, these wonderful hybrid beasts—centaurs, human figures with all sorts of grotesque features, chimeras with the head of one animal and the body or feet of another— cavorting around the text on the page; these are all features of Christian book cultures. Jews draw these figures by making the lines out of this miniature writing which contains the Masoretic text.

How did scribes get away with figurative representation over the objection of the rabbis?

In fact, the idea that the second commandment prohibits the making of any representational image is incorrect; what the commandment prohibits is worshipping such images. (At best, it prohibits making three-dimensional images.) You don’t find Jewish art everywhere and at all times, but there is a continual tradition of Jewish art and design, especially in books and, somewhat paradoxically, in books (and objects) connected to the liturgy (like ancient synagogue mosaic floors). In any case, Jewish scribes were their own bosses, with their own guilds, their own conventions. And they didn’t listen to rabbis. They wrote what they wrote. Later, this was true of printers, too.

I enjoyed many of these images but I had trouble reading the micrography in the pictures in your book. Could people actually read it?

Some of the pictures in the book are actually a little too small. When you look at the manuscripts themselves, it’s amazing often how clear the writing is. Lucidity of writing has nothing to do with size but has to do with the clarity of the scribe’s script.

Readers are probably familiar with the way a traditional Torah with commentaries, a mikra’ot gedolot, is laid out. Can you explain how that came to be?

That actual page layout—with a text surrounded by its commentaries—is not a Jewish layout; it comes from Christian-glossed Bibles. At some point, Christians thought to write their notes not in the margins, but in the grid of the page. The new form probably came to the attention of Jews through moneylenders, who would take valuables from Christians as guarantees of the loan: ritual objects from churches, royal objects from princes or kings . . . we actually owned the crown of England for about 30 years during the Hundred Years’ War! Can you imagine that? Anyway, they sometimes took valuable manuscripts to guarantee the loans, a number with this particular page layout. And we know they were taken by Jewish moneylenders because they often have inscriptions in them that would say that.

How did this new layout change the way Jews read their Bibles?

For Christians, the page was originally designed as an economical teaching tool—one book featuring both the text and its correct interpretation. Jews adapt this page in three columns: biblical text, Aramaic translation (Targum), and Rashi’s interpretation. (Rashi was read as a kind of indispensable guide to plain meaning of the Torah, or at least the accepted authoritative meaning of the Torah.) This leads to a very different way of writing scripture—reading verses sequentially but pausing over each verse independently. But the real effect of the layout was that by having Rashi and other commentaries on the same page as the Biblical text, it made reading the Bible with a commentary the normative mode of reading and studying the Bible.

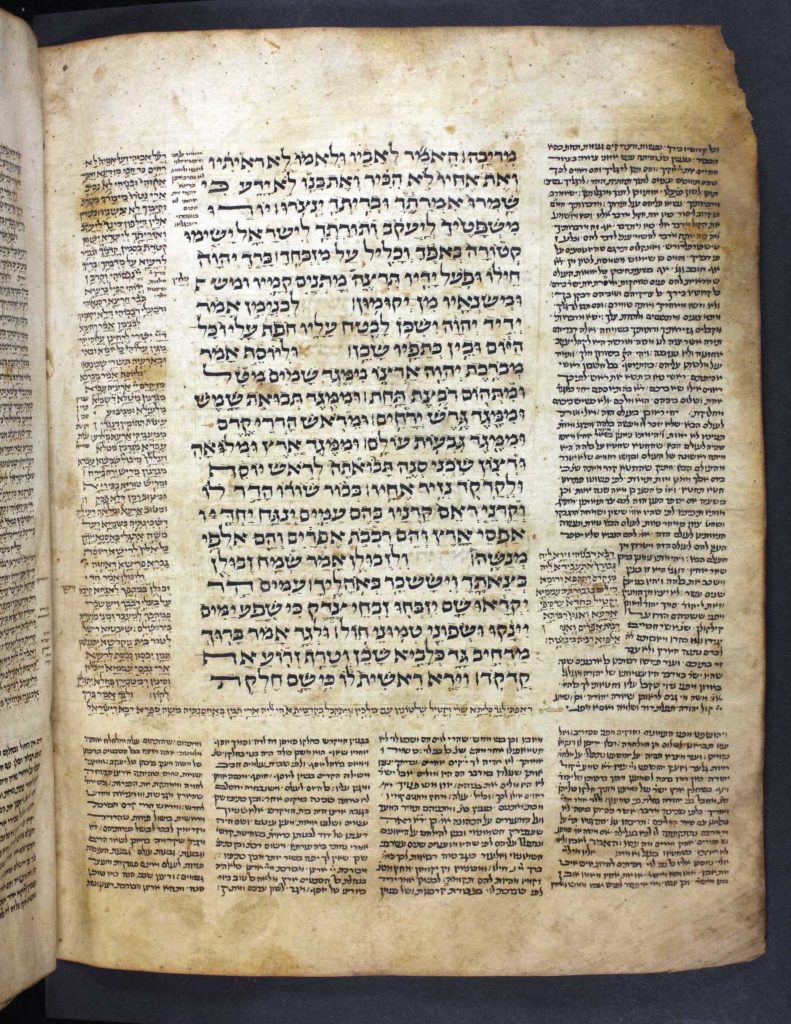

Then, the three-column format morphed into something more elaborate. If you look at the manuscript on page 119 of my book [shown here], you can recognize the three columns but it actually looks like a kind of cubist deconstruction of the typical three column page, say on the facing page—on 118.

This page, it looks like a jigsaw puzzle. The columns contain commentaries and tell you what the Bible actually means, but this page as a whole is telling you everything possible the Bible could mean. It’s showing you the richness of the Bible’s meaning, not a single authoritative meaning. In Jewish tradition, there is no single authoritative meaning of the Bible. That’s what reading the Bible is for Jews, it’s about finding the richness of the possible meanings of the biblical text, not finding the correct orthodox or authoritative meaning of the text.

That actually sounds a lot like ancient interpretation—multiple meanings.

Yes, and this brings us back to the relationship between the text and the book, and the ways that the material shape of the book influences how we understand the meaning of the text.

In the rabbinic period people only had scrolls. And remember that scrolls are extraordinarily expensive. It takes an average of something like 80 skins to make a Torah scroll, each skin is one animal. The human labor, the scribe’s work, is the least of the expense—even today. Very few people, almost no one, owned their own Torah scroll. The way the rabbis seemed to know the Torah—actually acquired their knowledge of the Torah’s text—is not as a text they read with their eyes in a Torah scroll, so much as a text that they acquired by hearing it chanted aloud and then memorizing it. This would have happened in the synagogue service and in educational settings. The rabbis “learned” the Torah in much the same way that bar or bat mitzvah boys and girls learn their Torah portions today. They memorized it.

Once Jews adapt the codex, you begin to find the first evidence for widespread knowledge of the Torah from actually reading it on a visual surface. And that makes an enormous difference in how the Bible is interpreted.

When you know a text through having heard it chanted aloud and then memorizing it, and you have a question about the meaning of a word or who a named figure is, you do not do a visual search—flip back pages in the book to find another place the word or character appeared—but you do a search in your brain, and you do it by sound. And that’s why in midrash you find all these aural puns between words and verses that have no other connection to one another.

Can you give us an example of a word that is interpreted one way through an aural knowledge of the text and another through visual knowledge?

Sure. In Genesis 22:1, God tells Abraham to take Isaac to the land of Moriah (eretz ha-moriyah) and offer him there as a sacrifice. There are many problems raised by this verse, and one of them is that no one knows where the land of Moriah is; it’s not on any map, and the Bible doesn’t tell us where it is. Now this was already a problem in the Biblical period itself, and in the Book of Chronicles, Mount Moriah (not the land, but a mountain) is identified with the Temple Mount, which makes sense. Where else but on the mount that would become the Temple Mount would God want Abraham to sacrifice Isaac? Now the rabbis inherit this identification but they still want to know why the Temple Mount is called Moriah. And to answer that question, they propose a number of answers all of which are based on aural puns. For example, it was called Mount Moriah because “Torah” went forth from it. Or morah “fear [of God”] went forth. Or because mor (myrrh) incense was offered there. You can hear the pun between Moriyah and all these words and terms.

Once they begin reading the verses on a page and acquiring that knowledge from a visual experience, then they begin to look at the text in a wholly different way. If you can’t figure out what a word means, you look at its spatial context: the verses before and after it or the chapter at large, the previous chapter. Or you find the answer in the way the word is spelled and written, which is something you have to see. This is a completely different way of solving problems. And neither one is better than the other; they’re just completely different.

So how does a reader of the Genesis verse who knows the book from seeing it on the page of a codex solve the problem of Moriah in Gen. 22:1? Rashbam, one of the great French 12th-century commentators, says that the Hebrew word “ha-moriyah” is actually a shortened version of ha-emoriyah, “[the land of] the Emorites” who are one of the Canaanite nations. What Rashbam means is that there was originally an aleph in the word—a silent consonant that takes on the sound of whatever vowel is attached to it, in this case, “e”; and that, because the e-vowel follows the definite article ha- (“the”), the aleph got dropped from the word because its sound of e blended into the preceding sound, ha. Now there is only one way Rashbam could know that the aleph was missing from the word. He had to see it on the sheet or page he was reading. But this does more than just explain what ha-moriah means. It changes the sense of the entire story. When the rabbis say Mount Moriah was the Temple Mount, the identification gives the story a kind of cosmic significance and makes it look forward to all the sacrifices that would later be made on the Tempt Mount. If Moriah is the land of the Emorites, God could just as well have told Abraham to sacrifice Isaac in New Jersey. The identification robs the story of all its mythic power.

In recent years, you’ve written a lot on the materiality of Jewish books, but you used to write more on classical rabbinic literature (I’m thinking here of Parables in Midrash, Midrash and Theory). How did you move from this focus on rabbinic literature to the history of the book?

I started out as a writer of fiction (I published stories in Response in the 70s, and I have a story in the first issue of Moment Magazine), but that’s a separate story. Some people think my scholarship is fiction! [Chuckle]

The first field I became interested in was midrash because it had unusual literary features, somewhere between a commentary and a primary text. But after 10 to 15 years and two books, I had more or less solved all the problems that had intrigued me about midrash.

I found myself hunting around for something to do that would intrigue me as midrash originally had. At the time, I taught at UPenn and there was a faculty workshop on material book history. There was a different paper every week on anything from Shakespeare to pornography in South Africa. I wasn’t working on anything like that, but I used to go and lurk just because it was so interesting. The guy who ran it, Peter Stallybrass, was infectiously enthusiastic. One day he asked me if I would give a paper. I felt I couldn’t turn him down because I had been attending, but at the same time I didn’t really have anything I was working on and I told him that. And he said: What’s that book you have with the really funny format? And I said: the Talmud? And he said: Yeah, the Talmud! Where does that page format come from? And I said: That’s a really interesting question, let me look into it, I have no idea. I started looking into it and I became totally obsessed with that topic.

Shortly afterward, I was invited to give the Stroum lectures at the University of Washington, and I recklessly volunteered to give it on three Jewish books: the Talmud, the prayer book, and the Passover haggadah. I spent about a year preparing those lectures and that’s how I first really immersed myself in the field, but it’s taken me 15 years since then to learn enough to actually write a book.

Any particular Bibles with unusual histories?

Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig wrote what is probably the greatest modern translation of the Bible (into German) and for my next project, a history of the Jewish book through 150 mini-biographies of specific manuscripts and printed books, I wanted to find one of their copies. It turns out that after Rosenzweig died, his family wanted to give his library to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. They packed the books up and shipped them to Palestine. When the ship docked in Tunis to refuel, the Tunisian government (for reasons I don’t know) decided to seize its contents, including Rosenzweig’s library. So where is Franz Rosenzweig’s personal library today? In the National Library of Tunisia. When I found this out, I went to the website to see if I could confirm it. But the catalogue is all in Arabic, so I emailed a colleague at Harvard, a professor of modern Arabic history, who works on Tunisia. She connected me to a woman in the library who helped me locate the book. So, if you want to see the books owned by the greatest Jewish philosopher of the 20th century, you have to go to Tunis.

This claim in your book is surprising to me: “At least so far, the digital revolution has not led to any truly revolutionary changes in the Bible’s materiality, as it has, for example, in the Talmud and the Jewish prayer book.” The digital revolution hasn’t changed the Bible’s materiality even though it has altered the Talmud? Please explain.

Websites like sefaria.org and alhatorah.org, which gather the Bible together with its commentaries in navigable formats, are great for teachers and students making source sheets and handouts—but they don’t change the basic way people read the Bible with commentaries. The case of the Talmud is different. With Talmud manuscript comparison sites, it’s much easier to discover that a problem in the Talmud stems from the fact that the text is corrupt, because you can compare manuscripts. And the Bar Ilan Responsa Project gathers virtually every text of classical rabbinic literature from ancient period through the Middle Ages and even into the modern period, uniting all of rabbinic literature into one corpus. In the case of the siddur and mahzor, it is very easy now to write your own prayer book. You can cut and paste from any texts you want, take what illustrations you want. This has already happened with the Passover haggadah. I predict that in the case of the prayer book, the great next division in religious Judaism is not going to be over the question of gender equality or egalitarianism, but over who will use an e-book on Shabbat and who will not. Once the prayer book becomes an e-book, a rabbi will be able to create a different service for every Shabbat, which will return Jewish prayer to the state it was in the 3rd century when each synagogue had its own prayer service. This is revolutionary, but with the Bible it’s harder to think that any change like this will happen.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Free Radicals

The history of American anarchists, and of Jewish anarchists in particular, has been forgotten, largely overshadowed by the history of the American communist movement.

Everything Is PR

Peter Pomerantsev’s narrative of “the surreal heart of the new Russia” features pink heels, private helicopters, and fantastical Midsummer Night’s Dream parties with trapeze artists and synchronized swimmers dressed as mermaids.

The Golem of Montreal

The famous golem of Prague was invented by a forger, faith healer, amulet salesman–and the most enterprising kosher chicken slaughterhouse supervisor of Montreal.

The Lost Textual Treasures of a Hasidic Community

The Regensburg Library at the University of Chicago contains a catalogue of markings and stamps from books saved from Nazi destruction. One such stamp comes from the library of the Karlin-Stolin Hasidim, a collection that might contain the most valuable manuscript for understanding the roots of Hasidism. But where is it?

Miryama Ausch

"We actually owned the crown of England for about 30 years during the Hundred Years’ War!" WE? We are not amused. The subject is tedious and esoteric for non-academics and no amount of Woody Allen-ish flipness will change that.

Justin Jaron Lewis

I was also taken aback by "we owned the crown of England" - lest it confirm the paranoia of any antisemite who might happen to read this. BUT I found the article utterly fascinating, with one intriguing, thought-provoking point after another. I will try to make sure my university library gets this book.