A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

When Jewish inmates of the Vilna Ghetto returned home after a day of slave labor in the city, they had to pass inspection at the ghetto gate, a frightening prospect for those smuggling food for their starving families and even more dangerous for members of the Fareynikte partizaner organizatsye (United Partisan Organization, known as the FPO), the armed resistance movement, who often smuggled weapons and ammunition. One day in July 1943, the poet Shmerke Kaczerginski, hid another type of contraband: rare rabbinic books strapped to his body inside a Torah cover. Manning the watch was not a member of the Jewish police, which often looked the other way, but an SS officer known for his sadism. As David E. Fishman recounts the incident in The Book Smugglers:

From a block away you could hear the shrieks of inmates being beaten for hiding food. The workers around Shmerke reached into their clothing. Potatoes, bread, vegetables, and pieces of firewood rolled into the street. They hissed at Shmerke, his puffed-up body obvious. . . . “Dump it. Dump it!” But Shmerke wouldn’t unload.

Just as he reached the head of the line, the SS officer left the gate and Kaczerginski accomplished his mission:

In a secret bunker deep beneath the ghetto, a stone-floored cavern excavated from the damp soil, metal canisters were stuffed with books, manuscripts, documents, theater memorabilia, and religious artifacts. Later that night, Shmerke added his treasures to the desperate depository. Before resealing the hidden doorway into the treasure room, he bade farewell to the Torah covers and old rarities with a loving caress, as if they were his children.

Kaczerginski was one of a group of ghetto residents who risked their lives to save the legacy of Jewish culture from Nazi plunder. It also included the linguist Zelig Kalmanovitch, who underwent a religious awakening during the war and became known as “the prophet of the Vilna ghetto”; Herman Kruk, who arrived as a refugee fleeing Warsaw and headed the ghetto library; the high school teacher Rachela Krinsky, who became Kaczerginki’s lover; and the great Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever. Close friends and members of the literary group Young Vilna in the 1930s, Kaczerginski and Sutzkever organized what came to be known as the paper brigade.

An aesthete with a belief that literature possessed an almost supernatural power, Sutzkever composed powerful poems in the midst of the Holocaust in the faith that he could cheat death as long as he continued to create. Yet it is not the refined Sutzkever who is Fishman’s hero but the colorful, earthy Kaczerginski. A true folksmentsh (man of the people), Kaczerginski was a communist who had led a hardscrabble existence, but his lively, outgoing personality won him friends from all walks of life. His poems, less innovative and more tuneful than Sutzkever’s, were often set to music. Many became popular in the Vilna Ghetto and are still sung today.

At the outbreak of World War II Vilna had enjoyed a period of relative calm under Lithuanian and then Soviet rule, so many residents hoped that Vilna could ride out the war unscathed. But within six months of the arrival of the German army on June 22, 1941, over half of the city’s Jews had been shot and buried in mass graves at Ponar on Vilna’s outskirts. Living Jews were not the Nazis’ only target. A mere week after the initial Nazi foray into Vilna a member of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the Nazi agency in charge of looting cultural property in occupied territory, arrived to survey local libraries, museums, and art collections.

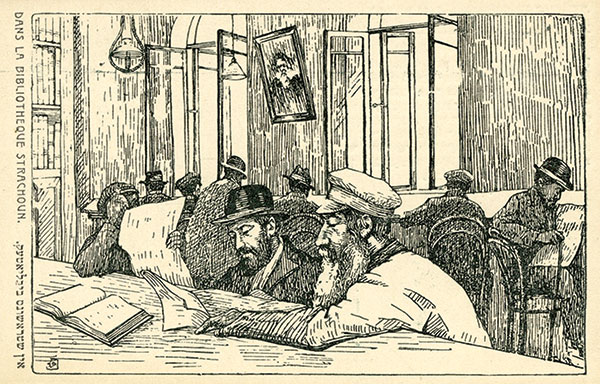

Vilna, which was known as “the Jerusalem of Lithuania,” was a special prize. Its legendary status as a center of Jewish learning was symbolized by two great institutions. The Strashun Library stood in the heart of the traditional Jewish quarter and was famous for its collection of rabbinic works. In a newer part of the city stood the Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut (Yiddish Scientific Institute, known by its acronym YIVO), the first center for Yiddish scholarship, which was rooted in a secular vision of the Jewish people as a modern nation. Since that nation lacked a state of its own, the YIVO headquarters became an international symbol for Yiddish-speaking Jews, the equivalent of a national language academy, university, and library rolled into one.

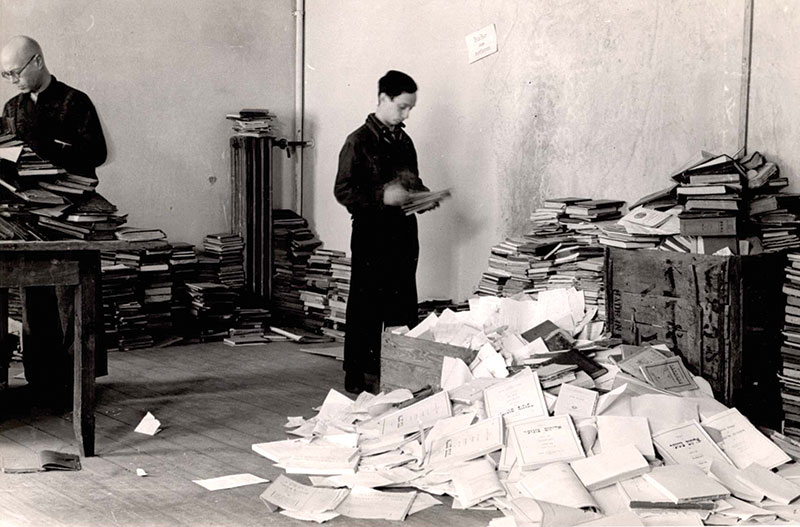

When the Nazi archivist-looters of the ERR returned to Vilna in early 1942 they set up several sorting centers, including one in the YIVO building itself. There they assembled a team of slave laborers who were forced to comb through the YIVO collections as well as books, documents, and art and ritual objects looted from local libraries, museums, and synagogues. The most valuable were shipped to Germany to be used for “Jewish research without Jews,” once the work of extermination had been completed. As it became clear that what was not shipped away would be destroyed, the workers faced a heartrending predicament. Fishman describes the enslaved Jews’ anguished realization that they themselves became “responsible for life-and-death decisions about the fate of cultural treasures.” He quotes Kruk, whose diary is the single most complete account of the Vilna Ghetto:

Kruk, the librarian, shuddered as he recorded the moment when the book dumping began, in early June 1942: “The Jewish laborers who are engaged in this work are literally in tears. Your heart breaks just looking at the scene.” As someone who had built libraries, first in Warsaw and then in the Vilna ghetto, he recognized the full magnitude of the crime that was unfolding.

Zelig Kalmanovitch was similarly tormented:

His emotions once burst forth at a literary program in the ghetto where he was the featured speaker. When the chairman introduced him as “the guardian of YIVO in the Vilna ghetto,” Kalmanovitch jumped out of his seat and cut him off: “No, I’m not a guardian; I’m a gravedigger!”

As they came to this agonized conclusion, a group led by Kaczerginski and Sutzkever decided to organize the paper brigade. In addition to smuggling material under their clothes when they returned from YIVO to the ghetto, they created hiding places in the YIVO building itself. Sympathetic Lithuanian contacts also played a crucial role by taking items to conceal in other locations in the city. Among the many treasures they saved was the 18th-century pinkas (register) of the Vilna Gaon’s elite study group, or kloyz; the diary of Theodor Herzl, which YIVO had purchased from his son; and letters and manuscripts from leading Jewish writers such as Sholem Aleichem and I. L. Peretz. They even found a way to transport large artworks by Mark Antokolsky, Ilya Repin, and others. Some questioned the decision to risk so much for mere artifacts. As Fishman quotes Kaczerginski:

“Ghetto inmates looked at us as if we were lunatics. They were smuggling foodstuffs into the ghetto, in their clothes and boots. We were smuggling books, pieces of paper, occasionally a Sefer Torah or mezuzahs.” Some members of the paper brigade faced a real moral dilemma whether to smuggle in books or foodstuffs for their family. There were inmates who criticized the work brigade for occupying itself with the fate of papers in a time of a life-and-death crisis. But Kalmanovitch replied emphatically that books were irreplaceable; “they don’t grow on trees.”

More than just a dramatic tale, Fishman’s story of “the Auschwitz of Jewish culture” seeks to reframe our understanding of the Holocaust itself:

Most of us are aware of the Holocaust as the greatest genocide in history. . . . But few of us think of the Holocaust as an act of cultural plunder and destruction. The Nazis sought not only to murder the Jews but also to obliterate their culture. They sent millions of Jewish books, manuscripts, and works of art to incinerators and garbage dumps. And they transported hundreds of thousands of cultural treasures to specialized libraries and institutes in Germany, in order to study the race they hoped to exterminate.

If the eradication of Jewish books was as important to the Nazis as the extermination of Jewish bodies, then the fate of libraries, archives, and art collections is central to understanding the Holocaust. In insisting upon this, Fishman draws upon the insight of his subjects:

He [Kruk] also noticed the parallel between the fate of Vilna’s Jews and their books. “The death throes of the Yiddish Scientific Institute are not only long and slow, but like everything here, it dies in a mass-grave.”

Over 40 years later Abraham Sutzkever recalled how “the evil ones undertook to transform [the YIVO headquarters at] Wiwulskiego 18 into a Ponar for Jewish culture, and they ordered a few dozen Jews from the Vilna ghetto to dig graves for our soul.”

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself. In the ghetto, the newly religious YIVO leader Zelig Kalmanovitch viewed Nazi persecution as a punishment from God for the sin of assimilation, yet even he came to see the work of the paper brigade as necessary:

[H]e blessed the book smugglers as a pious rabbi: “The workers are rescuing whatever they can from oblivion. May they be blessed for risking their lives, and may they be protected under the wings of the Divine Presence. May the Lord . . . have mercy on the saving remnant and grant us to see the buried letters in peace.”

Facing the jeers of fellow Jews desperate for food and firewood, the members of the paper brigade rejected the dichotomy between physical and cultural survival. Thus, it is not surprising that Kaczerginski, Sutzkever, and fellow ghetto inmate Abba Kovner were at the same time poets and partisans. Fishman writes that Kaczerginski was as proud to smuggle books for the paper brigade as he was to smuggle arms for the FPO:

In his memoirs, he recounted a folktale: When the Lord created the first Jew, the biblical patriarch Abraham, the Almighty gave him two presents for his life journey—a book, which Abraham held in one hand, and a sword, which he held in the other. But the patriarch became so fascinated reading the book that he didn’t notice how the sword slipped out of his hand. Ever since that moment, the Jews have been the people of the book. It was left to the ghetto fighters and partisans to discover the lost sword and pick it up.

Sutzkever made a similar point powerfully in his famous poem “The Lead Plates of the Romm Press,” in which he imagined melting the plates of the famous Jewish printing house for bullets:

Liquid lead brightly shining in bullets so fine,

Ancient thoughts—in the letters that melted hot.

A line from Babylonia, from Poland a line,

Boiled, flooded together, in the foundry pot.

Jewish valor, hidden in word and in sign,

Must now explode the whole world with a shot!

Fishman writes in a lively, accessible style, eschewing academic jargon and emphasizing the suspense and colorful personalities of his story. In an author’s note, he writes that he has “taken the liberty of imagining the feeling and thoughts of my protagonists at various moments,” and his account sometimes reads like a spy novel, but it is based on meticulous historical detective work in six countries and as many languages. Occasionally, one wonders whether this or that literary embellishment was necessary. The doomed romance between Kaczerginski and Rachela Krinsky, for instance, would be affecting even without allusions to their “erotic energies” and passionate trysts. Less salaciously, the emotional recovery of salvaged materials in the 1980s might have been a stronger scene without the remark that “Never before was the cataloging work of librarians and archivists accompanied by so many smiles and tears.” But these are minor criticisms of a gripping work with broader implications. Generally, these are left for the reader to infer, but, at one point, Fishman addresses the question of why these men and women risked their lives for books and papers, writing that it was both an existential statement and an act of faith:

The existential statement was that literature and culture were ultimate values . . . Since they were sure they would soon die, they chose to connect their remaining lives, and if necessary their deaths, with the things that truly mattered. . . . The book smugglers were also expressing their faith that there would be a Jewish people after the war, which would need to repossess its cultural treasures. . . . Finally, as proud citizens of Jewish Vilna, the members of the paper brigade believed that the very essence of their community lay in its books and documents. If volumes from the Strashun Library, documents from YIVO, and manuscripts from the An-ski Museum were saved, the spirit of the Jerusalem of Lithuania would live on, even if its Jews would perish.

Caught in the Nazi death trap, these individuals dedicated themselves to a source of transcendent meaning as human beings, as Jews, and as natives of Vilna: the written word.

There was hope that however many Jewish souls were exterminated, the Jewish people would endure and that this sheyres-hapleyte (surviving remnant) would take up the preserved fragments of its culture. It was this hope that accompanied the surviving members of the paper brigade as they returned to Vilna after liberation, Sutzkever from Moscow (his literary talents were so renowned that Soviet authorities sent a military aircraft to transport him and his wife from the forests of Lithuania to safety in Moscow in 1944) and Kaczerginski from a Soviet partisan unit in the nearby forests.

On July 26, 1944, a mere 13 days after Vilna’s liberation, Kaczerginski, Sutzkever, and Kovner established a Jewish museum to house the recovered remnants of the city’s Jewish heritage (the YIVO building and all the material hidden within it had been destroyed). They also set out to collect documents generated in the ghetto by its Jewish inmates and German rulers, as well as some of the very first survivor testimonies. This work arose from yet another goal: to now hold the Nazi tormentors accountable for their actions.

Shmerke, Sutzkever, and Kovner conceived of the museum as a continuation of both the paper brigade and the FPO. . . . [They] intended to use different types of material (the ghetto archive, Gestapo archive, and survivor testimony) to ensure that murderers would be brought to justice and punished. They saw the Jewish Museum as a framework for continuing the battle against the German murderers and their local collaborators, with trials and evidence instead of guns and landmines.

When Sutzkever was invited to testify at the Nuremburg trials as a witness of Jewish persecution, he read a German document found in the Vilna Ghetto into the court record. It was the first time such evidence had been submitted by a victim of Nazi crimes.

As Vilna’s small Jewish community struggled to reestablish itself, the limits of Soviet support for Jewish culture soon became all too clear. Here Fishman sheds new light on Soviet Jewish policy, in particular the dynamic between Moscow and local bureaucrats. The museum’s associates worked in rooms of the former ghetto prison while fighting to secure permits, space, and staff. They found Lithuanian officials uncooperative at best. On one occasion the Trash Administration sent 30 tons of recovered Jewish papers to be recycled as Sutzkever and Kaczerginski frantically ran from office to office, seeking to have the order rescinded. As Kovner wrote,

Across the city, precious Venice imprints, manuscripts, and unique items are being ripped apart, trampled upon, and used to heat ovens, and we are not given the opportunity to save these treasures. For two years, we risked our lives to hide them from the Germans, and now, in the Soviet Union, they are being destroyed. . . . Sutzkever and I have had dozens of meetings with ministers, the Central Committee of the Communist Party, and other important persons. They all promise, but no one helps.

First Sutzkever and more slowly the communist-leaning Kaczerginski came to realize that they had to rescue these materials once again, this time from the Soviet regime. They began clandestinely handing over packages to various emissaries headed to New York, where YIVO had relocated in 1940. When they themselves finally emigrated they smuggled along what they could via Poland, Prague, and Paris. Now guilty of the theft of Soviet property, they did their best to cover their tracks. Here Fishman’s research particularly shines, though the tangled tale of how these packages made it out from behind the Iron Curtain will never be fully unraveled.

The smuggled documents joined another remnant of the Vilna YIVO; what the ERR selected for shipment to Germany had remained intact and was discovered by the Allies near Frankfurt after liberation. Thanks to the energetic efforts of Max Weinreich, YIVO’s only surviving leader, 420 crates of material arrived in New York in July 1947. The museum in Vilna that Kaczerginski, Sutzkever, and Kovner had established was closed, along with other Jewish institutions, in 1949. Its holdings were transferred to other repositories and disappeared from sight for the next 40 years.

With the advent of perestroika in 1988 startling news reached New York: Jewish materials had survived in Vilna. Kaczerginski’s best-case scenario had come true, for while these items had been hidden in the Lithuanian Book Chamber its director, Antanas Ulpis, had resisted pressure to destroy them. Now YIVO staff—including Fishman himself—traveled to Lithuania to view the discoveries. As YIVO Executive Director Samuel Norich and Chief Archivist Marek Web greeted Ulpis,

a staff member brought in a handcart with five brown paper bags wrapped with string. The staff member unwrapped them and took out documents written in Hebrew letters. Norich and his archivist were speechless. . . . Many of them bore YIVO’s stamp.

This, they realized, was a portion of YIVO’s prewar Vilna archive. Negotiations commenced with Lithuanian authorities to regain possession of the materials, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. Instead, beginning in 1995, the archival documents were brought to New York, where they were duplicated and then returned.

As a young archivist at YIVO, I too was present as some of these events unfolded. I remember Fira Bramson, who cataloged the Jewish finds in the Book Chamber in the 1990s, addressing a YIVO staff meeting in her genuine Lithuanian Yiddish, bringing the first eyewitness account of collections believed destroyed decades ago. I remember examining these documents myself, crumpled, dirty, and in total disarray. But perhaps my most memorable experience was the day I was assigned to make photocopies for a visitor to the archives. His aristocratic bearing and the deference he was shown left me too intimidated to speak to him. It was Abraham Sutzkever, examining items in the Sutzkever Kaczerginski Collection that he and his comrade had hidden, rescued, and smuggled

to safety.

The final chapter of this story is still being written. In 2015 YIVO reached an agreement with the Lithuanian Central State Archives and the National Library of Lithuania to catalog and digitize the surviving Jewish materials in Vilna. As work proceeded new caches were discovered, revealing that more prewar documents remained intact than anyone had previously imagined. New resources are now available online, ensuring that the Vilna treasures will be preserved, made accessible, and reunited virtually with YIVO’s New York collections. The heroes of The Book Smugglers deserve no less.

Suggested Reading

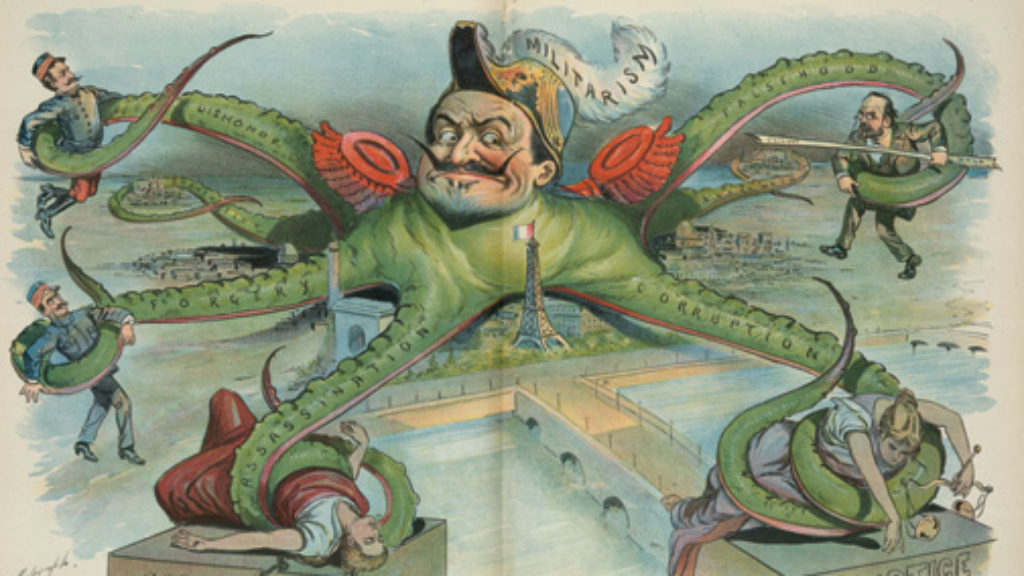

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

Haman, Builder of Towers, Brother of Abraham?

A new book raises the possibility that interpretive motifs from within both Jewish and Islamic traditions might have led to the uniquely Islamic tradition that Abraham and Haman were brothers.

Moses Mendelssohn Street

Immortality in Jerusalem.

Stemming the Yuletide

As the Yuletide rolls in, one finds oneself yearning for some Hanukkah pop with a little more depth than Adam Sandler’s Hanukkah song.