Dress British, Think Yiddish

Stanley Kubrick was a Jew from Jewland. Raised in the Bronx, he was surrounded by Jewish friends and neighbors, some of whom became early artistic collaborators. Born in 1928, he lived his adult life in the shadow of the Holocaust, and, although he never realized his plan to adapt Louis Begley’s novel Wartime Lies, Holocaust imagery was surprisingly central to his films. Allegorical enemies wear Nazi-inspired uniforms; partially formed mannequins stand in for disfigured bodies; and the state as a source of violence is a master theme that recurs throughout his pictures. He self-consciously cast Jewish stars in key roles: Peter Sellers, Tony Curtis, Sydney Pollack, Shelley Winters, and, iconically, Kirk Douglas. Indeed, the movies he made with Douglas, Paths of Glory and Spartacus, were critical in cementing Douglas’s image as the muscular, moral Jew.

Kubrick even cast himself in the same biographical role long played by Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, and Max Ophüls: Jewish émigré director. He left America for England in the 1960s, and his most English movie, Barry Lyndon, is also his most obviously Jewish: Barry, the Irish outsider, tries to ingratiate himself into high society, only to be tripped up by his incomprehension of a moral code that gives sanction to some forms of violence (and greed) but not others. In Eyes Wide Shut, his final film, the protagonist sleepwalks through highly stylized, fantasy versions of the landscape of Kubrick’s early years as a photographer and filmmaker: Greenwich Village and Central Park West. So how is it that we’ve come to see Kubrick only as a controlling, austere, manipulative, reclusive genius from England?

In Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual, Nathan Abrams answers this question with a single word: misdirection. Abrams’s essential argument is that Kubrick buried his Jewish preoccupations and thematic concerns, distracting viewers with superficially Gentile alternatives. Dr. Strangelove is obviously an ex-Nazi, a Wernher von Braun figure. Yet an early character sketch, preserved in Kubrick’s archive, describes him as “a Herman Kahn type.” The grotesque absurdity of Strangelove’s autonomous Nazi arm misdirects us from the Jewish nuclear strategist, who, along with others, served as Kubrick’s proximate target.

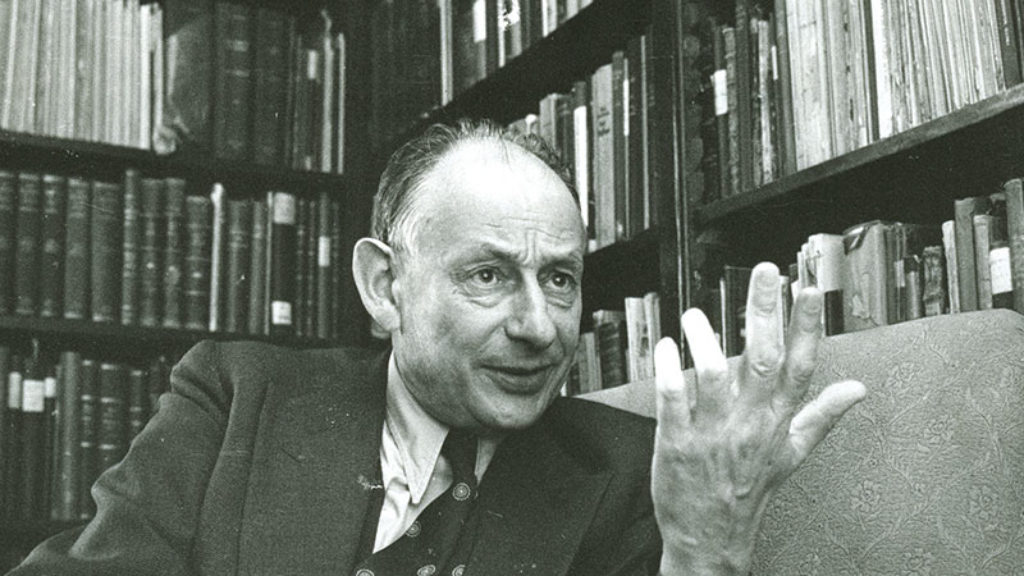

Abrams understands Kubrick not as a rootless cosmopolitan, but as a rooted one. This was a New York Jew, fascinated with photography, jazz, and chess. He took evening classes at City College and studied at Columbia with Lionel Trilling. Later, he moved to the Village and got to know Beat poets. He assiduously read intellectual journals and little magazines: Neurotica (the first Beat journal), Partisan Review, Commentary, Encounter (which published Trilling’s review of Lolita, a strong influence on Kubrick’s adaptation), Dissent. (In The Shining, Jack Torrance reads the New York Review of Books.) Kubrick read the most important works of Holocaust history and studies of totalitarianism as they were published. In a scathing review of Eyes Wide Shut, Midge Decter recounted Kubrick’s biography and called him “a familiar figure.” She knew what she was talking about. He truly was one of them, Abrams argues, a New York Jewish intellectual. “And while he was never a writer or a literary critic, he read their magazines. He had a fondness for ideological speculation, he was Jewish by birth, and he strived self-consciously to be brilliant.”

More importantly, the substance of Kubrick’s work reflects many of the same preoccupations as his fellow midcentury Jewish intellectuals. He was endlessly fascinated by man’s capacity for evil and “ultraviolence.” The disturbance of A Clockwork Orange’s second act derives from the state-sanctioned torture that poses as rehabilitation, a technique that explicitly recalls Nazi experimentation. Paths of Glory and Full Metal Jacket both explored the dehumanization of war and the transformation of the moral individual into a killer. For decades Kubrick thought about filming a Holocaust movie, and he even asked Isaac Bashevis Singer about writing the screenplay. He came closest to making a version of that movie in the early 1990s, when he was working on adapting Begley’s Wartime Lies, but he abandoned the project, either because of the success of Schindler’s List or because of the enormity of the subject, the impossibility of capturing everything he had learned about the Holocaust in a single film. These were not merely professional or purely artistic concerns. In a remarkable interview from the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, Christiane Kubrick, his third wife and the love of his life, expressed relief that Kubrick gave up the project: “He became very depressed during the preparations, and I was glad when he gave up on it because it was really taking its toll.” The documentary omits the fact that Christiane had been inducted into the Hitler Youth during her childhood, and that her uncle, Veit Harlan, was the director of Jud Süss. It’s not hard to suppose that the preparations were also taking their toll on her. Kubrick even managed to extend his fascination with the Holocaust beyond the grave: The posthumously released A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, produced by Kubrick and directed by Steven Spielberg, contains horrific shots of violence against humanoid robots—those with the capacity to pass, which are therefore intolerable.

Abrams suggests that we understand Kubrick’s moral world through the contrast between “menschlikayt,” the distinctive Jewish ideal of human decency, and “goyim naches,” the things Jews supposedly don’t value. This framework would seem, as we say in Yiddish, farfetched, if Barry Lyndon didn’t hinge on a textbook definition of “goyim naches”: the rules of dueling. Barry is made and unmade in a duel, his one ethical act leading not to reconciliation but to ruin.

Abrams combines close readings of the films with intensive, archival research into the source material—scripts, production documents, and Kubrick’s personal papers and artifacts—which collectively tell a Jewish story. Kubrick nearly always adapted pre-existing material, and he nearly always removed explicitly Jewish characters and subplots from the original sources. Curiously, Kubrick would add Jewish elements (Dr. Strangelove originally featured the “rightwinger—half-Jewish” senator, John Applekuegel) only to cut them close to production. What Kubrick kept were, according to Abrams, coded “Jewish moments.” Abrams writes approvingly that “nonexplicitness” provides “the key to understanding Kubrick’s ambivalent, ambiguous, and seemingly paradoxical attitude toward Judaism.” We could somewhat less charitably think of this as a formula: Think Jewish, omit the name, ostensibly achieve the universal.

Another recurring theme of Abrams’s work is Kubrick’s Jewish humor. Again, there are tells: A placard advertising a Lenny Bruce performance at a burlesque show prominently appears in the background of Kubrick’s early film The Killing (1956). Barry Lyndon is characterized by an extremely dry wit in which high is always undercut by low. (The film opens with one of its beautiful, painterly shots of men on a bluff in the Irish countryside: “Gentlemen, cock your pistols!”)

But Kubrick’s Jewish humor unquestionably reached its apogee during his collaborations with Peter Sellers. “How did they ever make a movie of . . . Lolita?” the original trailer asks. Well, by not making a movie of Lolita. Kubrick’s version is a brilliant-if-frustrating amalgamation of Nabokov’s story and a slapsticky, shticky cat-and-mouse game. Kubrick and Sellers transformed Humbert Humbert’s alter ego Quilty from a spectral presence to true antagonist. The nervy atmosphere of its opening scene comes from treating the showdown between Humbert and Quilty like a Marx Brothers routine: The straight man meets the wacko. “Hey, you’re a sort of bad loser,” Quilty tells Humbert as they “play” ping pong; “I’m just dying for a drink,” he says drolly as a gun is pointed at him. The film, through Quilty, masks its exploration of evil through the semitransparent shade of the comic. “It’s hard not to read the characterizations as intentional, an inside joke, or a series of jokes, about Jews as Jews and stereotypes of Jews,” Abrams writes. Sometimes the joke is hardly inside. Quilty attempts to ward off Humbert’s advance by saying, “This is a Gentile’s house. You’d better run along.” And then there is the suggestion that Sellers modeled his own performance on Lionel Trilling, after watching Trilling’s discussion of Lolita with Nabokov on a talk show.

The chapter on Lolita is the most surprising and the most revisionary, but Abrams’s book is nearly always compelling. Nonetheless, some of Abrams’s readings of Kubrick’s protagonists as Jewish are too attenuated—or perhaps the protagonists were themselves too attenuated as Jews—for the reading to be fully persuasive. 2001: A Space Odyssey, for instance, is too other-worldly to sustain the New York Jewish frame.

At other times, the gravity of reading Kubrick as a Jew from New York is liberating. Abrams’s opening chapter on Kubrick’s early films—Fear and Desire, Killer’s Kiss, and The Killing—is an exciting reintroduction to the young director. While the taut crime story The Killing has developed a cult following over the years (the opening heist in The Dark Knight borrows from it liberally), Killer’s Kiss remains a lost gem. Shot in a rush on location, the movie radiates with the energy of getting to make something in and about the place that you love. New York shapes the characters and sparks the action. The male and female leads are connected and separated by an air shaft; they watch each other (though they pretend not to watch) through their close windows. Their actions are mirrors, the apartment building pushing them into a dance of observing and being observed. Later scenes trade this claustrophobia for the particular dread of a city at its most empty: the industrial waterfront after hours, loft factories, the cavern of Penn Station.

Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick’s last film, is the unlikely reprisal and opposite of Killer’s Kiss. Killer’s Kiss reveals the city in its natural state. Eyes Wide Shut’s city was constructed on a backlot, a New York imagined in exile. Abrams calls it the “summation of Kubrick’s career as a New York Jewish intellectual,” and he’s right to do so. An unfaithful adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (Dream Story), the movie serves as exhibit A of Kubrick’s method: Start with an explicitly Jewish source text, replace the Jewish protagonist with an empty vessel (Tom Cruise), but add new Jewish figures, a Jewish mise en scène (“Josef Kreibich’s Knish Bakery” prominently appears during Bill’s walks through Greenwich Village), and tackle Jewish preoccupations. Sydney Pollack’s Victor Ziegler, the film’s hairy antagonist, is an anti-Semite’s dream: a lecher and a manipulator whose wealth enables him to abandon the rules of conventional morality. The film’s orgy sequence is disturbing precisely because it is an unerotic abstraction of sex performed for the powerful. Cruise’s Harford, like Barry Lyndon, may know the password, but he does not belong, and everyone knows it. There are always gates, restrictions, a level the Jew who obeys the rules cannot attain.

Kubrick’s body of work is haunted by the movies he never made. He worked meticulously and deliberately, developing projects for decades but not completing them. Had he made his Holocaust movie with Isaac Bashevis Singer; had he adapted Traumnovelle with Woody Allen as the lead in the 1970s instead of Tom Cruise in the 1990s; had he filmed Aryan Papers—there would be no debate about Kubrick’s identity as a Jewish director. But the movies he did make nonetheless bear the traces of the Jewish preoccupations, which Abrams brilliantly uncovers.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Stemming the Yuletide

As the Yuletide rolls in, one finds oneself yearning for some Hanukkah pop with a little more depth than Adam Sandler’s Hanukkah song.

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

Cynthia Ozick’s Art and Ardor

Reading is a blessing and a curse in Ozick’s world, a gateway to heightened emotion and new experience and also a maze of cruel tricks and dead ends. Allegra Goodman reviews her latest novel.

Palestine Portrayed

The 1948 War and the problems it left unresolved have returned to the top of the agenda for both diplomats and historians.

gershonhepner

This was a fine review by Eitan Kensky of Nathan Abrams' book on Stanley Kubrick, but the howler, "goyim noches," which surely should have been "goyischer naches," attenuated my yiddisher naches. Of course if I had more menschlikayt I would not be howling,

[email protected]

asmith

Mr. Hepner, we heartily concur and, in fact, had a heated debate about this in during the editing process here at the Jewish Review of Books. The "goyim naches" formulation comes directly from Abrams book, and thus we retained it in the article.

Regards,

Amy Newman Smith, Managing Editor