Boundaries, Conversations, and the Reform Movement: A Response to Elli Fischer

Last week in the Jewish Review of Books, Elli Fischer responded to the novelist Michael Chabon’s controversial commencement address to the graduates of my institution, the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR). In his insightful analysis, Fischer focuses on Chabon’s ultimate rejection of borders and boundaries of any kind, and shows that a simple illogic pervades Chabon’s “paean to mongrels and hybrids.” Chabon, writes Fischer, “forgets that ‘mashups, pastiche and collage’ require difference.” I would add that the converse also holds. Differences bear meaning only in their encounter at boundaries, which are both tested and reaffirmed precisely when they are crossed.

Chabon sees our conceptual and communal boundaries as the walls of a ghetto, which is symbolized for him by the eruv, or Sabbath boundary. This, Fischer deftly shows, misunderstands this halakhic idea.

The “walls” of the eruv are, in fact, generally not walls at all. They are comprised only of posts and wires, on the premise that two posts with a lintel form a doorway. The eruv circumscribes a community with walls that are entirely doors.

Chabon speaks of Judaism as a “giant interlocking system of distinctions and divisions,” which underwrite chauvinist self-segregation, but, as Fischer shows, this has more to do with the shallowness of Chabon’s Jewish knowledge than the religion itself.

This critique resonates, but only if we truly want to take Chabon precisely at his word. Does a technical exposition of the eruv materially respond to Chabon’s affect and rhetoric? Allison Kaplan Sommer recently participated in a conversation on Chabon and his HUC-JIR commencement address, which matched Fischer’s response for its nuance. “If you look at it as manifesto, as a philosophy,” she said, “it doesn’t hold water. . . . Having no walls makes no sense.” However, Sommer argued we can learn from Chabon’s speech if we recognize that “it works as anger,” directed at particularly impenetrable and morally problematic Jewish barriers.

All the same, we need not interpret Chabon’s speech solely as a cri de cœur. Essentially, and perhaps unknowingly, Chabon dove into an ongoing conversation that emerged in 19th-century Europe, when scholars and rabbis from each of the modern movements reimagined Judaism in view of the Enlightenment and Emancipation. These movements grappled with the nature of Jewish boundaries, across history and in their own time. The project known as Wissenschaft des Judentums, or academic Jewish studies, sought to excavate the Jewish experience in history by rereading canonical sources and discovering new sources, not only for and by Jews but also about them. Eschewing the pieties of sacred history, Wissenschaft gave us much of the Jewish history that we modern Jews now take for granted

The protagonists of Wissenschaft differed in the balance they hoped to strike for the Jewish future between Jewish particularism and “enlightened” acculturation. The distinguished HUC-JIR historian Michael Meyer has pointed out that Wissenschaft straddled and pushed some of the same boundaries that we do today. Does Wissenschaft “face inward toward the Jewish community, the Jewish people, and the Jewish religion with the intent of strengthening these, or does it face outward?” Although they disagreed on much, none of these 19th-century scholars was satisfied with simply hiding behind the walls of an intellectual or cultural ghetto.

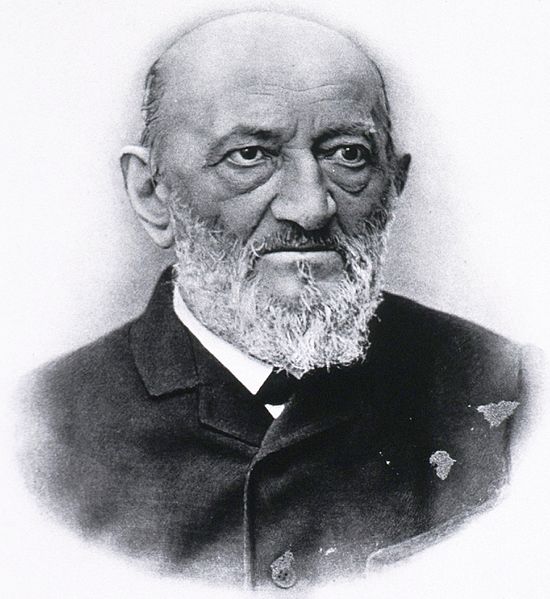

Chabon lands on the far universalist side of that debate. He can imagine countenancing the erasure of Judaism through assimilation into the universal mingling of cultures—though he would also mourn its loss. “If Judaism should ever pass from the world, it won’t be the first time in history,” he said. “Nor will it be the first time that an ethnic minority has been absorbed, one exogamous marriage at a time, into the surrounding population.” In doing so, he echoed, perhaps without knowing it, one of the founders of Wissenschaft, Moritz Steinschneider. A fantastically learned scholar of Jewish texts and a pioneer historian, Steinschneider rejected religion and, by extension, Jewish survival as a particularistic enterprise. (Gershom Scholem saw him and Leopold Zunz, his older contemporary, as “gravediggers and embalmers” of Judaism.) In this—in his way and for his own time—Steinschneider resembles Chabon, at least insofar as Chabon almost shrugs philosophically at the prospect.

Most founders of modern Jewish studies, however, resisted the prospect of radical secularization. Abraham Geiger, the progenitor of today’s Reform movement, worked as a pulpit rabbi, and he held on to his fundamental sense of obligation to Jewish community and, most of all, religion. He founded the Reform rabbinical seminary in Berlin, which was grounded in scholarship, while he proudly espoused Judaism as a religion that “has not permitted its belief in God to be disfigured by, and commingled with, extraneous elements.” Though Geiger and his Reform colleagues certainly held down the liberal side of the Wissenschaft movement, they did not, nor do we now, follow its most uncompromisingly secularizing trends.

Reform Judaism continues to participate in this same contentious conversation, not only with the Chabon–Steinschneider camp but also with the Modern Orthodox and Conservative heirs to Wissenschaft des Judentums. None of these expressions is fundamentally alien to one another. Through that multigenerational discussion runs a thematic thread: To push against boundaries is also to acknowledge them. Both the passions and flaws in Chabon’s speech make more sense in view of that fact. Chabon did not prescribe a future; he tested a boundary.

The graduation at which Chabon spoke was not the ceremony in which we ordain Reform rabbis. Instead, it celebrates the HUC-JIR’s role as the institution of higher learning for Reform Judaism and beyond. At graduation, we confer master of arts degrees in Hebrew letters, Jewish education, and Jewish nonprofit management on future professionals from the entire Jewish community. There, Chabon spoke to a wide range of people, from classical Reform Jews to Orthodox ones, including secular Jews and the proverbial “just Jews”—not only among the guests but also among the faculty and graduates.

This diverse audience naturally had varied reactions to the speech—and one can certainly question or defend the value of such controversy at a graduation ceremony. But the guests, graduates, and faculty by and large seemed to grasp the context of Chabon’s remarks. They were, after all, self-selected for Jewish knowledge and commitment, keenly aware of the challenges facing our community, and utterly engaged in American civic and cultural life. Their Jewish world view, no less than the legacy of HUC-JIR itself, was formed in the crucible of 19th-century Germany, even if not all of them specifically knew it.

Chabon’s extreme universalistic yearning and his oversimplified critiques of Judaism pushed hard against boundaries that we care very much about. But it is difficult to begrudge his admonition to us, not because we accept it but because it is hardly the first time we have heard it. As Sylvia Barack Fishman, Steven M. Cohen, and Jack Wertheimer wrote, “Chabon’s views are worrisome because among liberal American Jews they are not so outlandish.”

The pervasiveness of these questions derives from the modern Jewish condition itself—and that is very much the business and the tradition of HUC-JIR. Our task, like that of Abraham Geiger before us, is not to run from the irresoluble tension between universalism and particularism, but to allow the debate over it to expand our perspectives and to deepen our commitment to Judaism and the Jewish people.

Elli Fischer closed the conversation with Dean Halo in a final rejoinder.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Our Master, May He Live

Rashi's commentary on the Chumash isn't just about textual puzzles, it's about God's love for the Jewish people. So argues Avraham Grossman in a new biography.

Remembering the Plutocrat and the Diplomat

Most things in Berlin speak to the city’s troubled past, and the newly opened James Simon Galerie is no exception.

Says Who?

Peter Berger listened to me patiently, and then he said, “You can come to see me, but”—and here he spoke with heavy emphasis—“it sounds like you have read my books . . . and I haven’t thought of anything new.”

Universal Rights and the Particular Jew

Jews, like so many other minorities, whether they had states or not, deserve recognition and protection as nations. But these universal rights have eluded Jews, even as they worked to ensure them for others.

paul jeser

A very long defense of a horrible decision by HUC-JIR leadership. Bottom line - they brought in someone I believe is an anti-Israel self-hating Jew and gave him a pulpit to spew his garbage. Shame on HUC and its leadership!

pmchai

Giving Chabon's rants the same credence as writings of Moritz Steinscheider would be like saying that Donald Trump's politics are in the same camp as Leo Strauss. In some vague way, perhaps, but not really.

The piece by Dean Halo makes the invitation to Chabon seem a thoughtful decision intended to be provocative for intellectual reasons, a brilliant decision by Jewish educators with only the desire to push the Jewish identity envelope for the sake of high conversation. That all depends upon the decision-making process, of course, to which we are not privy.

But having read the speech twice and viewed the video once, I came away with the view that this was, indeed an explosion of anger by someone ignorant of Jewish history, for whom, by the way, the name Moritz Steinschneider is likely totally unknown. And this lengthy rationalization by the dean of the LA school of HUC-JIR to draw parallels in Jewish intellectual history is a desperate ex-post facto rationalization.

dennis.karpf

Dean Halo’s response to critics of and defense of Mr. Chabon’s commencement speech fails for two essential Jewish reasons. First, Mr. Chabon is no Rabbi Geiger, because Chabon’s argument and intention is not made under heaven for purposes of truth to help our faith. Rather, Mr. Chabon seeks secular victory, not truth, and destruction of Judaism. Secondly, the totalitarian and anti-democratic desire to destroy faith in God, Torah and Israel under the guise of equality or mixing of all belief systems (with no truth) is no different than the monstrous movements throughout history which have tried by power and force of arms to destroy freedom of conscience and freedom of faith. Simply put Mr. Chabon’s ideas do not deserve the dignity of Dean Halo’s response. Mr. Chabon’s nonsense is only given voice in the halls of the literature and humanities departments of our “elite” secular universities where these anti-Jewish ideas should remain. The fact that Mr. Chabon was given platform at HUC-JIR still remains insane.

Simon

I wish I could invite Gunther Plaut, Alex Schindler, Stanley Dreyfus and Malcolm Stern (among others) to call their offices, and perhaps Holo's office too. But alas, they are not with us. Then again, perhaps it is better that they did not see the fate of their movement. I appreciate the opportunity to read a piece that mentions the names Zunz, Steinschneider, Scholem, and Geiger, as it isn't every day that I get the opportunity. But perhaps it would have been better for Holo to simply say, "It was a foolish thing to invite him, which we did because he is a literary celebrity. It did not help our bid for relevance to the lives of Jews who actually make an effort to be Jewish, much less to those who actually have a demographic future." Less is more.