“In Order that They Didn’t Die Alone”: Remembering Claude Lanzmann

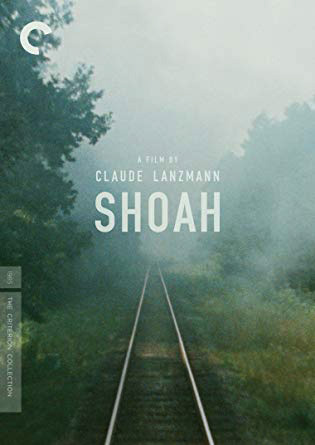

Claude Lanzmann directed what many critics consider the definitive film on the Holocaust, the nine-and-a-half-hour 1985 documentary Shoah. One of the survivors he interviewed, Abraham Bomba, served as a barber while a prisoner at Treblinka. The gruesome job forced on Bomba by the Nazis was to cut the hair of women and girls bound for the gas chambers. (The shorn hair was then used by the Germans in pillows and mattresses.)

Lanzmann took Bomba from his home in New York, where the survivor was living after the war, to a Tel Aviv barber shop and asked him to cut a man’s hair during the interview. Initially, Bomba tells his horrific tale in a muted monotone. But when he comes to the part of the story where he was commanded to cut the hair of Jewish prisoners from his own village, including his wife and sister, he breaks down, insisting he can’t continue. Lanzmann shouts, “You must tell it! You must tell it!” Sobbing, Bomba eventually puts down his scissors and completes his story. When criticized for his harassment of survivors, Lanzmann retorted, “One has to die with them again in order that they didn’t die alone.”

Claude Lanzmann died in Paris on July 5 at the age of 92. Born in 1925 to a secular Jewish family in the village of Bois-Colombes, near Paris, Lanzmann joined the communist resistance to the Nazis at the age of 17, smuggling arms and ammunition to the partisans. He came perilously close to being captured by the Gestapo.

After the war, Lanzmann became a close friend and colleague of the existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and the feminist scholar Simone de Beauvoir, joining the pair on the editorial board of the influential journal Les Temps Modernes. He also became romantically involved with Beauvoir, living with her from 1952 to 1959. When discussing the making of Shoah with journalist Roger Rosenblatt, Lanzmann said he learned from Sartre that all art—cinema or any other medium—must be “exhaustive,” which helps explain the length of Shoah.

Lanzmann’s first documentary, Israel, Why (1973), portrayed the Jewish homeland in largely favorable terms. After completing the film, Lanzmann was approached by the Israeli government, which funded him to make a movie about the Holocaust seen from “a Jewish perspective.” Originally, the film was supposed to be of ordinary length and completed in 18 months. When instead Lanzmann took 12 years, shooting more than 350 hours of raw footage, the Israelis eventually withdrew their support.

Lanzmann disliked the term “Holocaust,” which literally means “a burnt offering to God,” because he felt it gave the genocide an inappropriately religious aura. He titled his film Shoah, a Hebrew word meaning “catastrophe,” which, by then, had become the accepted Hebrew term for the Nazi-perpetrated genocide of the Jews.

Shoah is almost unique among Holocaust documentaries in that Lanzmann used no documentary footage, usually gleaned from Nazi archives, nor any fictionalized scenes. Instead, the movie is composed exclusively of interviews with those who became entangled, for one reason or another, in the Holocaust: survivors, witnesses, and perpetrators. Lanzmann justified this approach by insisting it was the only way to represent the Holocaust authentically.

Shoah is almost unique among Holocaust documentaries in that Lanzmann used no documentary footage, usually gleaned from Nazi archives, nor any fictionalized scenes. Instead, the movie is composed exclusively of interviews with those who became entangled, for one reason or another, in the Holocaust: survivors, witnesses, and perpetrators. Lanzmann justified this approach by insisting it was the only way to represent the Holocaust authentically.

After Shoah was released, Lanzmann became a constant critic of the slew of Holocaust films that took more license than he had with the historical record. He attacked Steven Spielberg’s 1993 blockbuster Schindler’s List, accusing it of “commodification” of the Holocaust, because Spielberg used professional actors and invented several scenes from whole cloth. Perhaps Lanzmann imposed excessively strict limitations on the boundaries of Holocaust representation. I don’t believe the Holocaust alone must be represented with no degree of artistic latitude—a demand not made of the portrayals of any other genocide. However, without question, Lanzmann’s narrow approach worked brilliantly in Shoah.

Most Americans first saw Shoah in 1987 when the film was broadcast in four segments on public television—a screening that also included Rosenblatt’s fascinating interviews with the cantankerous and opinionated director. Lanzmann’s directorial style eschewed the “fly on the wall” technique employed by many other documentarians, where the director serves purely as witness, taking no active role in the unfolding action. Instead, Lanzmann is a constant presence in his movie, both on and off camera, asking pointed questions that at times verge on badgering his often fragile subjects (like Abraham Bomba)—a technique that provoked disparagement from some reviewers.

Lanzmann’s protracted approach to his subjects is best illustrated in his extended interview with Jan Karski, a hero of the Polish resistance. Karski slipped into the Warsaw Ghetto before the Germans liquidated its occupants. What Karski witnessed there appalled him—starving children lying on the streets of the ghetto, while their fellow Jews stepped over their bodies without even glancing down, ghetto inhabitants so emaciated they resembled walking skeletons.

On escaping the ghetto, Karski traveled to England, where he met with the Polish government in exile as well as with British authorities. Eventually, Karski also went to America, where he spoke with President Roosevelt himself. Karski related the horrors he’d seen to everyone he met, but though his listeners were sympathetic, no government official took any action to save the remnant of European Jewry who were still alive.

In Shoah, Karski tells his story over and over again, often using virtually the same words. When I first saw this scene, I wondered why Lanzmann included every repetition, rather than using only Karski’s initial description as a more conventional director would have done. Eventually, I realized Lanzmann’s purpose was to convey Karski’s obsession with his ordeal. Karski literally couldn’t stop telling his story because it was the defining experience of his life. No wonder, then, that Lanzmann needed nine and a half hours to tell his tale in full.

Not only did Lanzmann interview survivors and witnesses, but he also spoke with perpetrators—another directorial decision that provoked controversy. For example, Lanzmann talked to Franz Suchomel, who had been an SS functionary at Treblinka and after the war was convicted of war crimes and spent six years in a West German prison. Lanzmann persuaded Suchomel to speak with him by pretending to be a Holocaust revisionist who wanted to “set the record straight.” Initially reticent, Suchomel became more garrulous as the interview progressed, until by the end he was regaling the director with a camp song composed by the SS. Lanzmann’s interview with Suchomel demonstrates that many perpetrators felt no remorse for their participation in genocide; if anything, they seemed to enjoy wielding the power of life and death over the helpless prisoners. Not surprisingly, some critics faulted Lanzmann for his imposture. But surely no director should ever have to apologize for tricking a Nazi.

Lanzmann’s last documentary, The Four Sisters, culled from unused footage from Shoah, was released in French theaters on Wednesday, the day before he died.

We also recommend Adam Kirsch’s review of Claude Lanzmann’s The Patagonian Hare: A Memoir (“Chasing Death,” Jewish Review of Books, Spring 2012).

Suggested Reading

Visualizing Hasidism

Everything contains sparks of the divine, the Ba’al Shem Tov and his disciples taught; therefore, everything—even material things—can be sanctified.

Back in the USSR

On the ephemeral nature of home and “certificates of cowlessness” in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region.

Proust Between Halakha and Aggada

Proust and Bialik were both great literary modernists, but they aren’t usually thought of together. Reading In Search of Lost Time in light of “Halacha and Aggada.”

Zionisms, Old and New

Arthur Hertzberg's classic anthology The Zionist Idea has received a 21st century makeover. But is the new version really an improvement over the old one? And what does Yossi Klein Halevi have to say in 2018 that hasn't been said before?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In