Repentant Prostitutes, Medieval Jewish Courts, and WWII Classified Ads

Although scholarly articles can be dense and difficult to access, they are often fascinating. Here’s a quick round-up of three interesting essays from leading journals: Association for Jewish Studies Review, Jewish History, and Jewish Social Studies.

The Repentant Prostitute

It’s an old storyline: Man meets woman, woman turns out to be wayward and wanton, man reforms woman, and the two fall in love. While it might be most familiar to us as Richard Gere and Julia Roberts’s story in Pretty Woman, there are late antique versions of the tale in Greek, Latin, and Syriac. Many versions of this story circulated among ancient Christians and usually underlined the message that repentance and salvation were possible for even the lowest members of society.

As Tali Artman-Partock points out in “The Tale Type of the Repenting Prostitute: Between Rabbis and Church Fathers,” the best-known Jewish version of the story has a very different cast. The Talmud (Menachot 44a; a variant is also found in the Sifre to Numbers) tells of a man who pays four hundred dinars to sleep with a celebrated prostitute who entertains her lovers atop a formidable tower of seven beds—silver and gold—bunked one on top of the other. The man climbs the ladders to meet her, lying naked and waiting on the top bunk. Just as he summits, his tzitzit rise of their own accord and slap him in the face, knocking him all the way to the ground.

Never having been rejected like this, the prostitute leaps down after him and demands to know what he has found lacking in her. The man admits that she is the most beautiful woman he has ever seen but ruefully explains that his fringes have reminded him of his obligation to the law. (Is their prospective congress illicit because they are not wed? Because she may be in a state of menstrual impurity? It’s not entirely clear, and, as Artman-Partock insightfully points out, the ambiguity may be generated by the fact that the story was not originally Jewish and therefore does not entirely “work” in a Jewish context.) Struck by the man’s commitment and forbearance, the prostitute finds out the name of his teacher, sheds most of her property, and becomes a disciple. Years later, now a convert and still in possession of those beds, she marries her would-be client.

Unlike Christian versions of the repentant prostitute story, which promise a universally available salvation, the Jewish version is about something completely different: the enormous reward (marriage to the most desirable woman imaginable) that follows from strict adherence to mitzvot—in this case, not sexual modesty but the “minor” (the Talmud’s word, not mine) commandment of tzitzit.

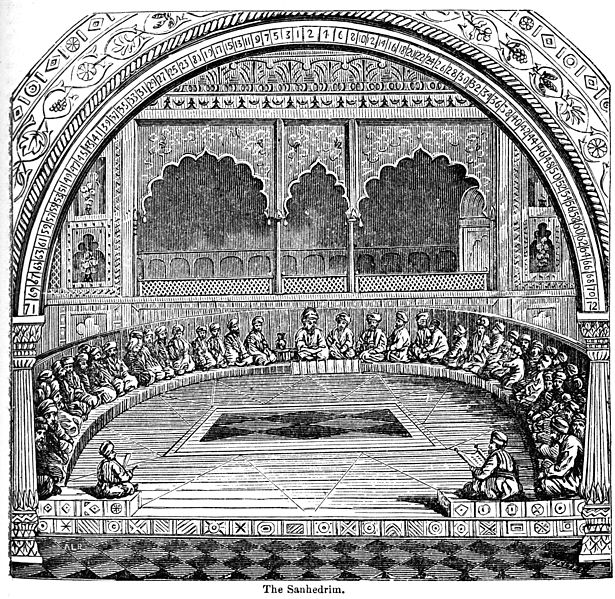

Medieval Jewish Courts: What Power Did They Really Have?

Critics and champions of Jewish tradition alike characterize Judaism as “legalistic.” Traditional Jewish texts are crowded with laws and references to courts and judges. But historically speaking, for a people who have spent most of their history living under the rule of non-Jews, how much of this legal tradition was, well, law? How did Jewish courts operate? And what power did they really wield?

In “Jewish Courts in Medieval England,” Pinchas Roth has given us a portrait of Jewish court operation in 13th-century England. Analyzing Latin official documents and Hebrew rabbinic documents, he shows that the Crown granted Jewish courts the right to settle cases between Jews. Jews, in turn, generally preferred to settle their differences in Jewish courts. As a result, Jewish courts were convened as needed with what judges were available. (Often, a court consisted of one rabbinic scholar and two laymen, though there were more prestigious courts composed of three rabbis.) Jewish courts heard a range of cases, but common disagreements centered on marriage, divorce, and money.

Because the Jewish community in 13th-century England was small and had close ties to the larger French Jewish community, English Jewish courts sometimes wrote to French authorities for advice. But the English Jewish courts maintained independent authority, not only from French Jewish interference but also from the English Crown, a relationship Roth describes as one of “mutual . . . limited respect.”

This relationship between royal and Jewish courts was disturbed only rarely, but in those instances the results were explosive—at least on parchment. This can be seen in the particularly evocative case of David of Oxford, a wealthy man with friends in high places, who sought to divorce his wife, Muriel. Muriel, who presumably enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle as the wife of one of England’s wealthiest Jews, sued her husband in Jewish court to block the divorce. The Jewish court denied David of Oxford his divorce, in keeping with a takkana (legal ruling) of Rabbeinu Gershom (10th–11th centuries) that forbade divorce against a wife’s will. David, eager to be rid of his wife, appealed directly to the Crown. The king, a friend of the aggrieved husband, issued a ruling that David should be granted his divorce and, furthermore, the Jewish court could not be convened again over this matter. But that was not all. A second royal order was issued, on the same day, to a different group of Jews, whom Roth identifies as most likely Muriel’s relatives, essentially shutting down the operation of all Jewish courts in England. Why this extreme reaction? Reading the letter carefully, Roth infers that Muriel, anticipating that her (ex-?) husband, David, would appeal to the English Crown, preemptively took her case out of the country to a French Jewish court, which ruled in her favor. The outrage of the king was a response to her effort to wield French Jewish authority over English royal authority.

But Roth points out that there was more at stake than the embarrassment of an English king being overruled by a few French rabbis in a divorce case. French–English relations were tense in the 13th century, so the close ties between English and French Jews may have appeared seditious. The rabbinic evidence suggests that this second decree, attempting to shut down all Jewish courts in England, was not enforced, since the English needed Jewish courts to resolve intra-Jewish conflicts. They continued to operate, in fact with increasing authority, until the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290.

WWII Classifieds

Personal marriage ads—those tiny newspaper notices that spell out, with stunning concision, the qualities an individual brings to and seeks from a potential match—provide an intriguing snapshot of a marriage market. And, as Sarah E. Wobick-Segev shows in “‘Looking for a Nice Jewish Girl . . .’: Personal Ads and the Creation of Jewish Families in Germany before and after the Holocaust,” these attitudes changed especially dramatically for German Jews with the rise and fall of Nazism.

German Jewish newspapers began carrying personal ads in the late 19th century. In that era, social standing and economic status, as determined by a man’s income and a woman’s dowry, were the main qualifications of a would-be groom or bride. Sure, men advertised their individual talents and occupations and women their beauty (specifically, slender build and blond hair) and religious upbringing. But aside from these desirable traits, socio-economic standing was king. If people were seeking a love match, they rarely wrote as much in the newspaper. Thus, the following ad from 1905 was typical:

Marriage! A very wealthy manufacturer from a very good family in Berlin with an annual income of 25,000 seeks to marry a young, beautiful lady with a dowry of at least 150,000.

As the Nazis rose to power, access to viable emigration routes became one of the most desirable traits in a potential spouse, though wealth and standing were not irrelevant. For example, consider this ad from 1938:

Businessman with American sponsorship, Jew, with large fortune, mid 30s, seeks to marry a well-off lady with a talent for languages and contacts in the USA.

On the eve of Kristallnacht, independent German Jewish newspapers (at that time there were 65) were shuttered. A few weeks later, the Nazis created a new Jewish newspaper, Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt, which, though run by Jews, was controlled and monitored by the regime. Cover to cover, the topic of emigration dominated its pages, and personal ads were no exception. Some were placed by individuals with an exit strategy already in place who wanted to take someone with them. Others were placed by those looking for someone with a way out:

Decisive! Capable 29 year old, Jewish woman by birth, able in foreign languages, good looking, cheerful disposition, without money or contacts abroad but with initiative, heart and mind, is looking for a truly harmonious life partnership abroad with a sophisticated, goal-oriented, loving man. (1938)

Of this heartbreaking ad, Wobick-Segev notes that even in desperate times, the desire for a loving partnership is expressed. In fact, in the “muted perspectives” of these tiny ads, the articulation of desire for matches that were not purely instrumental, but based on mutual affection, increased in dark times.

After the war, the German Jewish community was tiny but large enough for a new Jewish newspaper to start up. By 1946, Der Weg was publishing personal ads. Some singles continued to look for a partner with whom to leave the country; others offered a future partner stable housing in Germany. Some alluded to experienced trauma, to lost loved ones. Some sought a new mother or father for children who had lost a parent; others promised they could become a parent to bereft children. Some simply expressed the difficulty of finding a partner in a decimated and traumatized community. But nearly all of them, in one way or another, wrote looking for an emotional match. Love, it seems, was now a publicly expressed piece of the marriage equation.

Looking for something else to read? Consider Amy Newman Smith’s piece on letters and postcards sent during the Holocaust. Our previous academic round-up looked at articles about an ancient practice of tattooing the divine name, a Jewish adventure out West, and Haredi voting patterns.

Suggested Reading

Dionysus and the Schlemiel

If Judaism was a congenital disease, as Heinrich Heine imagined it was, it is only logical that he would eventually succumb to it.

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

A Comic Megillah?

Megillat Esther has long balanced the comic and the graphic in its content and interpretations. A new Koren graphic novel takes the challenge a bit more literally.

18 Questions with Dara Horn

Dara Horn’s new novel, Eternal Life, is out today. We caught up with her and asked her 18 questions.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In