Art Over Vitebsk

In his poetic first autobiography, Marc Chagall called Vitebsk “My joyful, gloomy city.” He was remembering the place of his birth and fin de siècle childhood, while simultaneously reflecting on discordant feelings about his departure. The Vitebsk of his early years was a provincial river city, a district capital in the northeastern corner of the Pale of Settlement. Rising off of river banks, it had worn and sloping cobblestone streets, electric streetcars, two large synagogues, 60 prayer houses, and 27 churches. A pedestrian bridge connected the stylish side of town with its neoclassical, Russian-style Governor’s Palace and its fashionable stores, including a pastry shop, to the other side of Vitebsk, where there were warehouses for shipping, a railroad junction, and a scattering of squat brick dwellings standing adjacent to shabby log buildings. Domes and bell towers illuminated the low horizon.

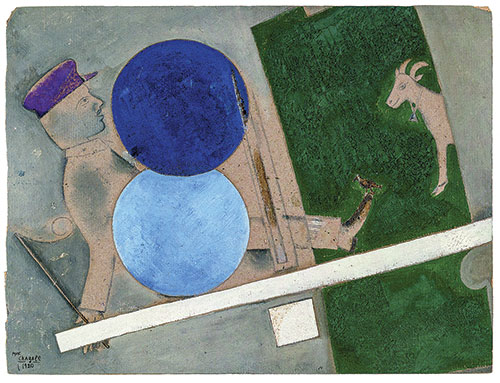

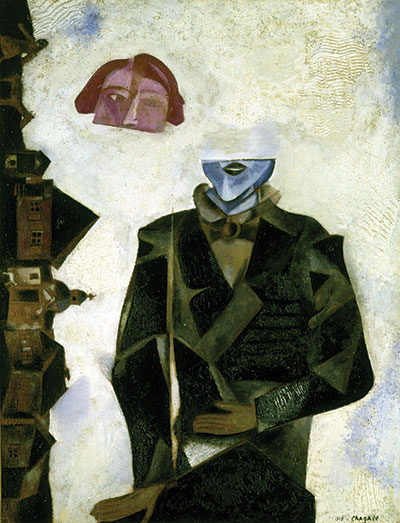

At the turn of the century, Vitebsk had a population of about 66,000 people, more than half of whom were Jewish. Although memories of the Russian pogroms of the 1880s lingered, many Jews were becoming professionals or moving into the middle class, joining Russian intellectual and political (even radical) circles, or taking part in the Jewish cultural revival with its flourishing Yiddish literature and theater. In his memoir, Chagall combined irreconcilable feelings about this complex place, allowing them to hang in opposition to one another like the two halves of his subject’s head, one reddish and the other blue, in his painting Anywhere Out of the World which he had completed a few years before.

From the start, Vitebsk had been a rich source of inspiration for Chagall’s visual storytelling. He raided it for his earliest subject matter when he expressively painted his bearded father wearing eyeglasses and a working man’s visor cap or, in contrast, his stylish emancipated fiancée with her hands covered in elegant black gloves. He reimagined it when he was a young man in Paris, creating a private iconography for what seemed a faraway and exotic setting, filling it with humanized cows and houses with peaked roofs that sometimes flipped upside down.

In 1914, he returned home for his sister’s wedding shortly before the beginning of the First World War. When the border suddenly closed, Vitebsk became a refuge for the war wounded, as well as thousands of Jews expelled from their homes on the eastern front. He documented their suffering, drawing and painting soldiers and displaced Jews. The following year, in the fine Vitebsk home of his wife’s parents, he was married, “under the wedding canopy, in the proper way,” and Vitebsk became the city he immortalized in Over the Town, in which he and his wife float above doll-sized houses and fences, gliding together in a cloudy sky.

After the revolution and because of his Paris friendship with the intellectual revolutionary Anatoly Lunacharsky, Chagall—somewhat implausibly—became plenipotentiary for the affairs of art in the province of Vitebsk and chairman of the city’s commission, entrusted with decorations on the first anniversary of the October Revolution. Buoyant with hopes for a more just and tolerant society, Chagall instructed both housepainters and art students to make wall murals, cloth banners, posters, wreathes, and red calico bows to adorn the city. An extraordinary 60,000 people took part in the events captured on a film commissioned by city authorities.

This summer, at Centre Pompidou, visitors were able to gaze at the still-impassive faces of cavalry soldiers in Vitebsk’s festooned Freedom Square one hundred years after the festivities. Soon after the celebration, in January 1919, Chagall became the founder and director of the Vitebsk People’s Art School. Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918–1922 revisits the phenomenon of postrevolutionary Vitebsk, where, against all probability, the avant-garde bloomed in a provincial Russian city dominated by Jewish culture. The exhibition ran from March 28 through July 16, 2018 at Centre Pompidou and traveled in a modified form to the Jewish Museum in New York, where it is on view from September 14, 2018 through January 6, 2019. The handsome accompanying catalog, edited by Angela Lampe, is available in both French and English.

Visitors should not be misled by the exhibition’s name; it contains more than just the three artists listed, giving us a glimpse at the work of the many artists Chagall brought to the school’s faculty, as well as the students, inspired by Kazimir Malevich, who became part of the UNOVIS collective (an abbreviation for what has been translated as “Affirmers for New Forms in Art”), which made public art for Vitebsk and other cities. The exhibit in Paris was lavish, with 250 objects, paintings, works on paper, books, ceramics, and sculpture, including a life-sized construction of Lenin’s Rostrum, based on the design developed in the architectural studio of Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (he renamed himself El Lissitzky in homage to El Greco) at the Vitebsk People’s Art School. It also displayed postcards, letters, photographs, and journal extracts, enlarging our ability to reimagine the spectacular collision between modernism and revolution that occurred in a provincial capital for a fleeting moment before it was extinguished by history.

Due to the multiyear Russian embargo on art loans to the United States, materials from the Tretyakov Gallery, the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Pushkin State Museum cannot travel to the New York show, which will thus be missing several spectacular Chagalls, as well as Robert Falk’s beautiful painting of Vitebsk. Falk, a Russian Jewish postimpressionist, depicts the city’s white stone walls glistening in contrast to shadowed rooftops tinted in hyacinth, emerald, and vermillion. Though not all the artists were Jewish—Malevich, most significantly, was born into a Roman Catholic, Polish-speaking family in Ukraine—the story of Vitebsk emanates from the suffering, aspiration, and cultural vibrancy of Russian Jews whose creativity was entwined with the history and disturbed universe of modernism.

As the provincial plenipotentiary, Chagall encountered numerous difficulties from the start. This was the beginning of the bloody and chaotic period of War Communism, when businesses, factories, and food supplies were seized by the government, sending the country into economic chaos. With widespread shortages, events for the first anniversary celebration had to be limited. Though the festivities were a great success, Chagall was reprimanded by authorities for extravagant wastefulness and criticized by skeptics who found the revolutionary art, with its unrealistic colors, lack of proportionality, and distorted perspective, unintelligible. While hardly any of the decorations, from the first celebration have survived intact, we can look at David Yakerson’s sketch for Panel with the Figure of a Worker and imagine how it baffled spectators, with its sharp lines and architectonic angles depicting a laborer, in an Egyptian-looking pose, who seems about to move forward on impossibly large feet.

When the art school opened, it was simultaneously praised for the opportunities offered “for the working masses” while being disparaged for its “right-wing ways.” Chagall, who was never dogmatic, invited a broad assortment of artists, painters, graphic artists, designers, and sculptors representing many different trends to become part of the faculty; some, like Falk, were still making more-or-less representational art, while others, like Ivan Puni and Vera Ermolaeva, were more avante-garde. Many of the artists Chagall brought from Petrograd, where he had formed many friendships in the arts, stayed for barely a semester, and replacements had to be found. It didn’t take long for Chagall to feel overwhelmed by his administrative responsibilities. As early as April 1919, it was reported, “The artist Chagall appealed to the Center to release him from his duties as the Province Plenipotentiary on Matters of Art.” A curt telegram instructed him to “remain in his post,” but by May his request had been accepted, and another artist, Aleksandr Romm, took over as provincial plenipotentiary, with Chagall staying on as director of the Vitebsk People’s Art School. But even this was no small task; during the first semester, the school took in about 120 students, mostly boys in their teens, Jewish children of laborers. Again in September 1919 he tried to resign, but an assembly of students appealed to him to stay on, and he relented.

The real problems began when Lissitzky and, to a greater degree, Malevich joined the faculty. As in the culminating Passover song, Chagall invited Lissitzky to teach in Vitebsk and Lissitzky invited Malevich to join the endeavor, and Malevich brought disaster. In his official summary of the school’s first year, Chagall described his intention to maintain artistic diversity in the studios, “within our walls, the leading artists and workshops of all trends—from left to ‘right’ inclusively—are represented and function freely.” But the revolutionary and metaphysical arguments of Lissitzky and Malevich against figurative representations forced all of the teachers and students to take sides.

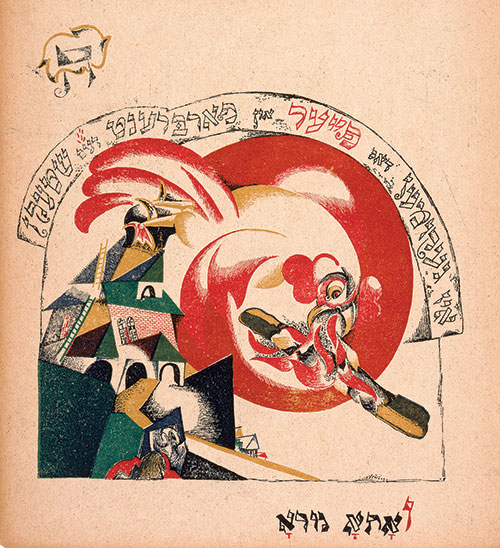

Lissitzky had known Chagall since childhood, when both were students at Yuri Pen’s art school in Vitebsk. Chagall’s magical expressionism strongly influenced his early work, which was also impacted by his training as an architect and his exposure to European art during travels abroad. Looking at the “Then Came a Fire and Burnt the Stick” page from his famous Had Gadya suite of colored lithographs, you see how Lissitzky integrated the new Cubo-Futurist style with everything that had come before for him: fire and firebird, Jewish tradition and Russian, word and image, Jugendstil and Chagall-like tumbling-over village houses, all conflated into the spiraling, red conflagration that symbolized revolution. But this balance was short-lived. After 1919, he dedicated himself to radical social utopianism and created the design for the Central Committee’s first flag, as well as the now iconic Constructivist poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, in which bold typography, a simplified palette, and symbolic geometry delivered the Bolshevik message with a jolt.

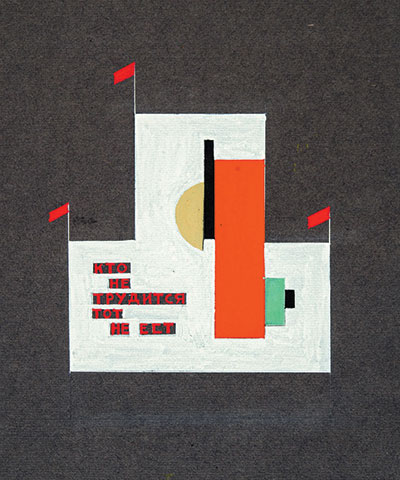

Malevich, the founder of Suprematism, had become the most famous of Russia’s avant-garde artists by the time he arrived in Vitebsk in 1919. Even today, much about Malevich’s artistic theory is impenetrable. Early on, he rejected the use of organic shapes in art and eventually even color vanished from his paintings. He thought of his 1915 painting Black Square as a “total eclipse,” and when he progressed to his red phase and then to white on white, even color vanished from his paintings. During the years he was in Vitebsk, he almost completely stopped painting and dedicated himself to theorizing about a new system of art, developing ways in which Suprematism would be applied to the world at large. In Vitebsk, he was armed with written rules, postulates, lectures, and a curriculum proclaiming the end of individualism in art. Under his influence, Lissitzky created a new, symbolic architecture on the painted surfaces of his canvases. Inventing the term “Proun,” “project for the affirmation of the new,” Lissitzky described his experiments using the new jargon from the factories; they were “the interchange station between painting and architecture.”

The Vitebsk students were captivated by the commotion generated in the workshops and mesmerized by Malevich’s charismatic, if not megalomaniacal, personality. The exhibits include photographs showing how they wore the emblem of the black square sewn on their sleeves to honor their teacher’s “great discovery,” and there’s a trove of memorabilia such as the 1920 manifesto for the UNOVIS collective and the 1922 diploma awarded to the young Suprematist Lazar Khidekel. It didn’t take long for many of Chagall’s students to transfer to Malevich’s studio.

Today the experience of viewing Malevich’s Black Square or Lissitzky’s Proun canvases, with their rough and splotchy surfaces, is similar to looking at antique weapons. The blades are still sharp, but the world they were intended to cut down has evaporated even as they persist as witnesses to its history. At the time, these weapons were strong enough to drive out Chagall and his quest for a pluralistic modernism. In June 1920, Chagall made his final resignation from the school. There’s no doubt he experienced his colleagues’ ideas as a personal attack; their Manichean tendencies were completely contrary to his own inclinations. In his autobiography, he wrote that he had been “expelled” from Vitebsk like the Jews who had been evacuated from the border towns in 1914 and found themselves homeless. He concluded his thoughts about the betrayal with a beautifully complex simile: “I shall be silent about my friends and foes. All their masks are piled up in my heart like lumber.”

Despite the school’s short life, for a time the work of the Vitebsk People’s Art School overflowed into the city. Working together with local craftsmen, UNOVIS adorned offices and workshops of the

Vitebsk Committee for the Struggle against Unemployment, the State Committee for Foodstuffs, and the Vitebsk City Theater with Suprematist panels, enormous signboards, and banners. One of the pleasures of the exhibit is to look at the rarely exhibited and spirited work of some these students, many of whom became artists in their own right. With its tiny flags, Nikolai Suetin’s Wagon with the UNOVIS Sign looks like a fanciful boat or, perhaps, a spaceship. The Suprematist compositions by Ilya Chashnik and Lazar Khidekel show utopian artists rebalancing geometrical arrangements to usher in an ideal world.

Not long after Chagall left Vitebsk, Lissitzky followed. Malevich stayed on to see the first and last class graduate, but departed in the summer when local Soviet authorities closed the school down. Many decades later, Chagall wrote in Memories: “They thought that if they could take possession of my school and all the students, a black square on a white canvas could become a symbol of victory . . . But a victory over what? I personally found none of the enchantment of color in this black square on its drab canvas background.” (With the rise of Stalin in the late 1920s, Malevich’s ideas suddenly became bourgeois and counterrevolutionary, but he managed to remain a Suprematist to the end, and his ashes were buried under a grave marked with a black square in 1935. Lissitzky died a Stalinist exponent of Social Realism in 1941.)

Chagall, who in 1915 had painted Anywhere Out of the World with those two red and blue halves of a single, if separated, head, was completely undoctrinaire. As a young artist in Paris, he had felt challenged by the brilliant experiments of Picasso and Braque’s Cubism. Staking out his own idiosyncratic and eclectic style, he intuitively bathed his fragmented work in illogical colors, filling the framework of his canvas with fantastical figures and objects that pleased him. Part of the strength of his work in Vitebsk, and later for the Moscow Yiddish Theater, came from the way he integrated Suprematism, Cubism, and Constructivism while simultaneously pushing back against the ideological pressures. He spoke directly of the world vanishing under his feet, and so his characters fly over a city that is being stamped out by modernism, revolution, and history to come.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Pew’s Jews: Religion Is (Still) the Key

Who are the “Jews of no religion” in the much-discussed Pew Research Center's “A Portrait of Jewish Americans”? It’s a question that gets at the deep structures of Jewish life and the inadequacy of many of the sociological methods used to describe it.

Zero-Sum Game

Most liberal Israelis once believed the 1990s-era Western narrative about Israeli-Palestinian peace: that the Palestinians would eventually be satisfied with a state alongside Israel, that everyone desired the same kind of progress, that maximalist rhetoric on the Arab side masked more modest goals, and that the Palestinian talk about millions of refugees and their “right of return” to Israel was a starting position that was bound to be bargained away.

One Nation, Two Disraelis

In locating Disraeli within modern Jewish history, the late David Cesarani engages with a tradition that he traces back to Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin, who placed Disraeli’s Jewishness at the heart of his private life, his novels, his political thought, and his career as a politician.

Repentance and Desire

Mizrachi identifies the heightened energy she senses in the streets of Israel during the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. She renames the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur known as the Ten Days of Repentance, “Aseret Yemei Teshuva,” as the “Aseret Yemei Teshuka,” or “Ten Days of Desire,” a time when the yearning for a return to God and Torah reaches a primal, visceral level.

jgurevitch

I just read this article--besides being informative and interesting, the language was just, well, delicious. I read the sentence with the analogy to antique weapons three times just for the enjoyment of the way it was worded. Beautiful writing! Now I need to arrange to go to see the show at the Jewish Museum.