Tweets and Bellows

A man, having gone insane, regains control of his mind by writing letters—“to the newspapers,” Saul Bellow writes in Herzog, “to people in public life, to friends and relatives and at last to the dead, his own obscure dead, and finally the famous dead.”

A society, having gone insane—caught in a fever, lost in a revolution or war—regains control of its narrative, the closest thing it has to a mind, by creating literature. Novels, histories, poems. It’s through writing and reading that a person or people can access the quiet part of their brain, the voice amid the chaos that explains who one is and what one must do. A person who reads has a different kind of focus and attention, a different kind of mind.

So, what happens when people stop writing letters? Or when books become less central to society—a tangential diversion or eccentricity—less important than movies, which are less important than the premium cable channels, which are less important than Netflix and Amazon Prime, which are less important than video games, all of which together are less important than social media? What happens when our writers and thinkers express themselves through Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter instead of on the page?

Herzog, which might be Saul Bellow’s greatest novel—published in 1964, it spent 42 weeks on the New York Times bestsellers list—is the story of a cuckold. College professor and intellectual Moses Herzog has discovered that his wife, Madeleine Pontritter, has been at it with his best friend, Valentine Gersbach, who, in a moment, has gone, in the mind of Herzog, from sage confidant to scumbag charlatan. The novel is also about women and men, sex, New York and Chicago, that great city, in all its weathers and glowering moods. The book is filled with characters. The childhood friends. The double-dealing psychiatrist. The shyster lawyer. The lingerie-wearing flower shop owner who steams up Herzog’s nights.

In one of the book’s most moving passages, Bellow recalls his mother explaining man’s place in God’s world, and it feels so true and so particular that it can have come only from Bellow’s life.

He remembered that late one afternoon she led him to the front-room window because he asked a question about the Bible: how Adam was created from the dust of the ground. I was six or seven. And she was about to give me the proof. Her dress was brown and gray—thrush-colored. Her hair was thick and black, the gray already streaming through it. She had something to show me at the window. The light came up from the snow in the street, otherwise the day was dark. Each of the windows had colored borders—yellow, amber, red—and flaws and whorls in the cold panes. At the curbs were the thick brown poles of that time, many-barred at the top, with green glass insulators, and brown sparrows clustered on the crossbars that held up the iced, bowed wires. Sarah Herzog opened her hand and said, “Look carefully, now, and you’ll see what Adam was made of.” She rubbed the palm of her hand with a finger, rubbed until something dark appeared on the deep-lined skin, a particle of what certainly looked to him like earth. “You see? It’s true.”

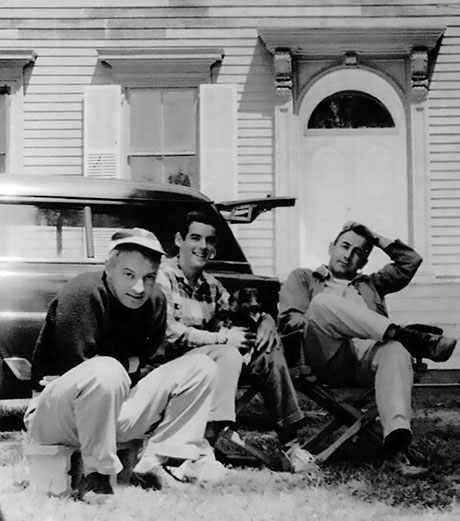

Bellow had a name for this process of literary transformation: It was the “higher autobiography,” not what actually happened but what it felt like and what it meant, a lost moment reanimated, recovered. The fictions of Herzog are the facts of Bellow seen through a glass darkly. He’d married Sondra Tschacbasov, his second wife, known as Sasha, in 1956. She was 16 years younger, beautiful and complicated. They’d met at Partisan Review, where Sasha had been a secretary. They moved to upstate New York and lived in a big house on the Hudson while Bellow taught at Bard College. He had a friend there, a professor with a bad foot named Jack Ludwig. Later, when Bellow took a job in the Midwest, he managed to bring their friends the Ludwigs along with them. It was only while working in Minnesota that Bellow learned that Sasha and Jack had been having an affair. She’d apparently been angry with Bellow, probably not without reason. He was self-involved and unfaithful, and the fierceness of his descriptions of Madeleine (“Will never understand what women want. . . . They eat green salad and drink human blood.”) should be tempered with the knowledge that you’re getting one, fictionalized side of a sad, complicated story. Bellow is not fair, but that’s literature. (Just ask the Amalekites.) And it’s the energy of the novel—the fury of the cuckold, a man driven insane not merely by betrayal or the break-up of a marriage but by humiliation, the sense that everyone knows and has known all along. “If I am out of my mind, it’s all right with me, thought Moses Herzog” is the book’s famous opening line.

Jack Ludwig, the bad friend with the bad foot, becomes Valentine Gersbach (“loud, flamboyant, ass-clutching brute”) with one leg—that’s how you amp it up; Minnesota becomes Chicago, because nobody knew that town, with its meandering river, “the sluggish South Branch dense with sewage and glittering with a crust of golden slime,” like Bellow.

The letters, which wind through the book like that sluggish, slime-covered South Branch, can be read for mental moods as well as secondary meanings. “Dear Dr. Morgenfruh,” Herzog writes to his old dead professor, “Latest intelligence from the Olduvai Gorge in East Africa gives grounds to suppose that man did not descend from a peaceful arboreal ape, but from a carnivorous, terrestrial type, a beast that hunted in packs and crushed the skulls of prey with a club or femoral bone.”

The letters also serve a therapeutic function. As anyone who’s spent serious time writing—hundreds of hours, enough to get outside the wake into the glassy water—can tell you, the pen (or keyboard) connects to a different part of the mind, or a different mind, than the one that chatters at you endlessly through the day. Bellow understood this, of course, and it’s that hidden mind that he sees as the way to carry Herzog out of the bad time and into something different (though his next marriage was also a mutual, maddening disaster).

Herzog wrote letters to order his thoughts; Bellow wrote a book, the one you are reading. It’s a dual operation that gives the novel a mysterious power. As the reader of the novel, you are the true addressee of Moses Herzog’s mad correspondence. The book is a kind of Russian nesting doll. You’re reading about a man purging his mind in a story written by a man doing the same. “Dear Dr. Bhave,” Herzog writes Vinoba Bhave, the Indian philosopher and Gandhi disciple, “I read of your work in the Observer and at the time thought I’d like to join your movement. I’ve always wanted very much to lead a moral, useful, and active life. I never knew where to begin.”

But if the book was just about this one man—or these two men, Moses and Saul—it might be limited, interesting and small, but Herzog is oceanic, not just about one man, or one kind of man, but about America dealing with the terrifying unraveling of the postwar narrative (“Dear General Eisenhower. In private life perhaps you have the leisure and inclination to reflect . . . The pressure of the Cold War . . .”). Which brings us to the current moment. How would Moses Herzog react to his crisis if it were happening today? Not spending hour after hour bent over yellow legal pads, writing in longhand (no one, other than my father, who is 85 and working on a memoir called Hello, I Must Be Cohen, writes like that anymore).

Herzog would be hunched over a laptop or an iPhone, not writing letters but texts, emails, tweets, updates to his Facebook page, tagging friends and enemies, celebrities and the famous dead. Take, for example, the most famous letter in the novel—Herzog half-deranged but still spot-on in his challenge to Heidegger. “Dear Doktor Professor Heidegger, I should like to know what you mean by the expression ‘the fall into the quotidian.’ When did this fall occur? Where were we standing when it happened?” That’s only 184 characters, which could actually be a tweet under the new Twitter dispensation. But with its proper diction and tightly controlled, philosophically channeled Jewish anger, Herzog’s deep, aphoristic letter doesn’t sound like one. A tweet, with its acronyms and ad hominem nonthought, sounds more like this:

Hey Marty @Dasein you Nazi Spengler-Nietzsche wannabe! GMAFB Tell us we fell into QUOTIDIAN but never say where when who with or why. Was that the SH*T you fell into in ’33? #Germanphilosophysucks #cannedsauerkraut

In other words, social media is not literature, and tweeting is not writing. The text, the tweet, the post—these hasty bits of content do not give access to the deep well of the hidden mind. They can’t make you better, but they can make you worse. Herzog, in the era of the status update, would not be a story with a happy ending.

Moses Herzog, tweeting at, instead of writing to, presidents, philosophers, friends, and enemies, would, in 2018, go from terribly bewildered to completely nuts. No one is getting saner in the Twitter storms that sweep the landscape daily, these freak weather systems of a collapsing intellectual and moral environment.

The solution is, as it’s always been, literature—a quiet room in back of the crazy house, a single light burning. But we can’t get to that room because we no longer have the time or patience to read those books. We’ve lost the habit. And the books we don’t read don’t get written. Welcome to postliterate America, where we are all deranged Herzogs, blasting our moods into the ether.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Wandering Jews

Jews have been travelers since God told Abraham to get up and go. How deeply has this constant motion been imprinted on the Jewish psyche?

The Great Whitefish Way

Larry David baked an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-meta stance into Fish in the Dark from the get-go.

Available Light: Pictures from Yemen

Yihye Haybi, a Jewish medical assistant to an Italian doctor in Sana'a, found himself in possession of a camera. Self-taught and working under difficult circumstances, he captured the waning days of Yemen's ancient Jewish community.

Thoroughly Modern Maimonides?: A Response

Kaplan writes that “one key statement . . . I would have liked to see Stern contend” with is “‘For only truth pleases God and only falsehood angers Him,’ [Guide 2:47] which implies that only truth, not the search for truth, is of value.”

anthony.connolly

Recently, I began deleting all of my social media accounts; the last to go will be Facebook because that deletion will be met with some resistance, and puzzlement on the part of family and friends. Oh well. It must be done. My brain is mush and my writing is only getting worse not to mention the deleterious attention span on account of social media nausea. Thank you Mr. Cohen for this piece, which further helps me along my way to a quiet room of my own, where the light will burn, the pen will travel and you're always welcome to come over for a cup of coffee, and conversation.

anthony.connolly

In the past few weeks I’ve begun to untangle myself from social media. My brain was turning to mush and my writing was suffering greatly. And forget any sense of memory. So I’m withdrawing to a degree to my quiet room to work when I can. The coffee is always on Mr. Cohen and you’re welcome any time to stop by for a cup and some conversation. Thanks for this great essay.

Alan

I think Cohen has gotten much of Herzon wrong, though I'm always glad to read about this important and masterful novel. The main thing Cohen gets wrong is his assertion that Herzog has "gone insane," (something Cohen repeats throughout his essay. The opening line of the novel, which Cohen quotes, is more a sign that Herzog is not insane and not crazy but has a rather healthy sense of self-deprecation. I believe Bellow describes Herzog's letters as a means of "having it out" (if my memory is correct), but in reading the novel many times, I never got the impression that Herzog was "crazy" or "insane" or that Bellow intended Herzog to be seen as such. He of course is a man with profound inner conflicts, but that is far from being insane. I also cannot credit Cohen's view that Herzog would be a Twitter-er or social media junkie (if Cohen really believes this). Herzog is portrayed as not really a man of his own time even in the novel; he is in many ways a relic of a more distant age; why would he be a man of our times if he was not a man of his time? So, no, Herzog was not intended to be seen as "half-deranged," "insane" or "crazy." Had Bellow made him so, Herzog would not been nearly as powerful or sympathetic or moving a creation. Repeatedly calling Herzog insane in his essay tells me Cohen has missed the extraordinary sanity of Herzog, a complicated but perfectly sane man living in a world that, as Cohen seems to understand, is what has become senseless and...insane.