Letters, Summer 2013

Kosher Tin Foil

Timothy Lytton, in his thought-provoking article “Chopped Herring and the Making of the American Kosher Certification System” (Spring 2013), is surely correct when he says, “The U.S. kosher market generates more than $12 billion in annual retail sales, and more products are labeled kosher than are labeled organic, natural, or premium.” However, the author neglects to mention that more and more of these kosher-labeled products do not need kosher certification in the first place! Many are not even foods.

Based on the Talmudic concepts of notein ta’am li-fgam (contributing a non-beneficial taste) and eino ra’oh le-akhilat kelev (not fit for a dog to eat), non-food items should not need kosher certification. But a quick glance at the current ShopRite Kosher Products Directory shows that this is not the case: The OU certifies as kosher aluminum foil, food storage bags, sandwich bags, foaming cleanser with chlorine bleach, antibacterial hand soap, laundry detergent, wool wash, sponges, heavy-duty scrubbers, hydrogen peroxide, and isopropyl rubbing alcohol.

As competition increases, it becomes harder for the kashrut agencies to grow. Perhaps this is what leads them to certify products that, according to the strict letter of Jewish law, do not require certification to begin with. This recent development is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, by adding kosher certification to products that don’t need it, the kosher consumer is forced to pay more when they could pay less without certification. Secondly, the agencies seem to be overstepping the biblical injunction of “thou shalt not add thereto,” (Deut. 12:32).

Rabbi Yossi Newfield

Brooklyn, NY

Timothy Lytton’s “Chopped Herring and the Making of the American Kosher Certification System” records, with admirable flair, the triumphs of the kashrut agencies. Indeed, the agencies have created an unprecedented mechanism, a kind of interlocking cartel of expert organizations that makes kosher-certified foodstuffs widely available to interested consumers. Perhaps this structure will serve as a model for other kinds of certification, such as food safety.

As Kohelet observes, though, “no human being is so righteous that he does only good,” (7:20). So too, human institutions, which have their own imperatives. Each kashrut agency exists to further fidelity to halakha, but what turns out to benefit the agency may not always coincide with halakha. The Orthodox Union, for instance, certifies glass cleaner, which benefits no one but the OU. To the extent that this certification gives the impression that glass cleaner requires inspection for kashrut (let alone that it is a beverage), the agency misleads the public.

The approach of kashrut agencies to genuine halakhic stringencies creates a more subtle problem. Faced with a stricture practiced by a small percentage of kosher consumers, there is a natural tendency to enforce that stricture on all consumers, to avoid losing the business of the strictest consumers. Moreover, the agency benefits as more consumers take on the stricture and so become dependent upon the agency.

For example, when a kosher slaughterer detects certain abnormalities in the lungs of slaughtered cattle, further investigation is required to determine whether the animal is kosher. However, historically, a few Ashkenazi Jews took on the added stringency of refraining from eating that meat entirely, even when investigation showed it to be kosher. This is the standard of keeping “glatt kosher.” Modern kashrut agencies have promoted this additional stricture, in pursuit of higher standards, in accordance with the economics of the centralized meat packing industry, and in their own best interest. In consequence, merely kosher, “non-glatt” meat has more or less disappeared from the marketplace.

However, the agencies certify as glatt the meat of cattle with some abnormalities. Thus someone who wants to keep the old standard of plain kosher must accept the additional stricture of glatt, and someone who wants to keep the old stricture of glatt must accept new leniencies pioneered by the agencies. Furthermore, some poultry now appears with agency certification, along with the legend “glatt,” even though the term is meaningless when applied to poultry, lamb, or veal.

In other cases, Jewish law clearly permits products that the kashrut agencies nonetheless prohibit. For instance, a bedrock principle of kashrut, enshrined in all the codes, holds that minor amounts of forbidden substances do not render the entire food forbidden. If the prohibited substance appears in a negligible amount, or if only a small possibility exists that the forbidden substance actually is present, the food remains permitted. This is the principle of bitul, or nullification. While no one contests its validity, agencies typically refuse to apply it. Thus, in an article titled “When It’s Null and Void,” Rabbi Dovid Heber of the Star-K agency reports that “most kashrus agencies do not rely on bitul. This means that Star-K policy is that products must be 100% kosher to be granted certification. Star-K does not allow companies to add non-kosher ingredients.” Since Jewish law permits these products, the agencies clearly have other goals beyond enforcing Jewish law.

In showing preference for stricter rulings, the kashrut agencies are, of course, part of a larger halakhic trend to rule strictly and even to issue rulings based on contradictory theories, in order to be yotzei le-khol ha-deot (in conformity with all opinions). Many factors drive this general preference for stringency, including piety, fear of sin, and some less-wholesome motives. In the case of kashrut, it is at least partly driven by the institutional interests of the kashrut agencies themselves.

Rabbi Eliezer Finkelman

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Timothy Lytton Responds:

Rabbis Newfield and Finkelman suggest that kosher certification sometimes has more to do with marketing than with Jewish law. They allege that leading certifiers provide unnecessary certification to non-food products. In defense of this practice, Rabbi Yaakov Luban, an executive rabbinic coordinator at the OU, explains that many companies believe that kosher certification offers them a marketing advantage—a kind of rabbinic Good Housekeeping seal of approval—and that the OU provides certification even though the agency does not consider it necessary, provided that there is some halakhic basis for doing so. In the case of aluminum foil, for example, the OU has posted on its website an article detailing concerns about the use of non-kosher oils in the production process. Ultimately, consumers must judge for themselves whether transparency about the role that marketing plays in certification of non-food products legitimizes the practice and whether the use of non-kosher ingredients in products such as aluminum foil raises legitimate halakhic concerns. Certification is, of course, harder to justify in the case of products that never come into contact with food, such as bleach and floor cleaner.

Rabbi Finkelman additionally alleges that agencies promote excessively stringent standards in order to gain competitive advantage over other agencies by appealing to a broader range of kosher consumers. He suggests that this practice is driven by agency self-interest. The agencies respond that it demonstrates their responsiveness to consumers’ religious preferences. The two views are not incompatible. As I argue at greater length in my book, kosher certification is both a business and a sacred trust. Indeed, it is precisely the combination of profit motive and moral commitment that makes kashrut a model for reliable private certification—albeit an imperfect one, as Rabbis Newfield and Finkelman rightly point out.

Greek Guilt

Thank you for publishing Prof. Devin Naar’s article on Salonica (“Jerusalem of the Balkans,” Spring 2013). Naar’s mention of the religious aspect of Salonica Jewry was particularly welcome. The importance of Salonica as a religious center is often ignored.

While Naar makes interesting observations about changing attitudes to Salonica’s history, he overlooked the similarly changed understanding of Greek Christian collaboration during the Holocaust. Although long denied, the question of local collaboration is now prominent in Holocaust history as a whole, including that of Greece in particular. It is well known that officials of the Greek collaborationist administration helped the Germans on numerous occasions to target Salonica’s Jews. In July 1942, Vassilis Simonides, the governor-general of Macedonia whose administrative headquarters were in Salonica, complied with a German military decree conscripting thousands of Jewish men for forced labor and helped the Germans enforce the mass call-up. Demobilized Greek military officers oversaw the forced laborers, sometimes abusing them, while Greek engineers supervised the projects. The conditions of forced labor were harsh, men were beaten and worked to death.

Greek officials participated in the German extortion of a massive ransom in October 1942 to free the forced laborers. The ransom included the surrender of the historic Jewish cemetery of Salonica. Naar claims, “The story of the destruction of the Jewish cemetery—once the largest in Europe—remains largely shrouded in silence.” It isn’t. Joseph Nehama and Rabbi Michael Molho, whose book Naar mentions, stated explicitly in 1953 that the municipality of Salonica was involved in destroying the Jewish cemetery. Documents relating to the demolition of the cemetery, carried out by Greek Christians, have long been available in German archives.

The extent of Greek official accommodation to the Nazi persecution of the Jews was such that in January 1943 the Germans gave the collaborationist government close to two months’ warning of the deportations. The Greek collaborationist administration used this time to communicate and enforce German anti-Semitic orders, such as expelling Jews from civic associations, forcing Jews to wear the yellow star, banning Jews from public transport, and putting Jews into ghettos. The Greek police guarded the ghettos and then took the Jews to the railway station as of March 15, 1943 for the journey to supposed resettlement in Poland. When Italian consular officials sought to provide certificates to seventy-five Jews claiming Italian protection, the Greek state’s Aliens Bureau confiscated the documents. The Germans deported many of these Jews to Auschwitz. The government in Athens and the local administration in Salonica oversaw the massive theft of Jewish property.

Naar’s omission is surprising, as Greek anti-Semitism during the Second World War was a topic at the conference that took him to Salonica. Just three days before the conference, Greek national television broadcast a documentary, Ektos Istorias (Outside of History), that examines Greek Christian assistance to the Nazis during the deportations of the Jews. The documentary undermined the officially propagated myth that Greek Christians overwhelmingly rejected Nazi racism and sought to assist the Jews. None of this is “shrouded in silence.” Historians have chosen to avoid these issues.

Andrew Apostolou

Washington, D.C.

◊

Chinese Jews

In his review of The Haggadah of the Kaifeng Jews of China (“Why Is This Haggadah Different?” in the Spring 2013 issue), David Stern alludes to the all-too-common moralizing that is done regarding the fate of the Jewish community of Kaifeng, China. True, the Jews of Kaifeng never experienced persecution and, equally true, the community has very nearly disappeared, but the reason has less to do with “intermarrying with native Chinese” or “their astounding success in assimilating to Chinese culture” or “their gradual loss over the centuries of Hebraic and Judaic literacy” than, as he more correctly notes, “their near-complete isolation from Jews elsewhere in the world.” That a group of Jews who only numbered about six thousand in its heyday managed to survive at least one thousand years, even to the present day, is a tribute to their perseverance and endurance, rather than attributable to their assimilationist tendencies.

Furthermore, as Dr. Jordan Paper writes in The Theology of the Chinese Jews, 1000-1850 (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012), his groundbreaking study of the beliefs of the Kaifeng community, there is hardly any difference between what the Kaifeng Jews did vis-à-vis the Chinese people and culture and what Jewish communities around the world did in their encounters with their host cultures and peoples: They acculturated and they interbred. Why else do European Jews look like Europeans and Ethiopian Jews look like Ethiopians? Why else do we have European-influenced (i.e., Christian-influenced) Jewish philosophy and Islamic-influenced Jewish philosophy?

The prospects for the long-term survival of the Kaifeng Jewish community were from the very outset endangered by its small numbers. For several hundred years, the international trade that flowed to and fro along the Silk Road and the sea lanes provided them with information and materials that enabled them to reinforce their Jewish identity and practice. But around the year 1500, the Ming rulers issued a series of decrees prohibiting travel between their domains and foreign lands. Meanwhile, the various Jewish communities in other Chinese cities disappeared or relocated, leaving the Kaifeng Jews utterly alone. To this was added the series of floods and wars which repeatedly destroyed the synagogue, Torah scrolls, and texts. And lastly, the economic decline of the Jewish community mirrored that of China as a whole beginning in the late 19th century. It is a wonder that they survived at all!

What is truly miraculous is that, today, thanks to China’s relative openness, the wonders of the Internet, and the number of Western Jews visiting Kaifeng, the Chinese-Jewish descendants are undertaking a cultural revival. One young woman has built a Jewish museum in her ancestral home, there are plans to create a cultural center, and some young Kaifeng Jews are studying in Israel. Last but not least, there are two competing Jewish schools and kehillot—does anyone need further proof of their Jewishness than this? Readers interested in learning more about the Kaifeng Jews, and about Jewish life in Shanghai and elsewhere in the modern era, should visit the website of The Sino-Judaic Institute, www.sino-judaic.org.

Rabbi Anson Laytner

Past President, The Sino-Judaic Institute

Seattle, WA

◊

Unto the Third Generation?

My grandfather was born in Sokoly, Poland, in 1900 and was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1926. I grew up in the Conservative movement, not only under my grandfather’s influence but also influenced by our synagogue’s services, Hebrew School, USY youth activities, and other programming. Therefore, I read David Starr’s review of Michael Cohen’s The Birth of Conservative Judaism: Solomon Schechter’s Disciples and the Creation of an American Religious Movement with great interest.

Starr laments the Conservative movement’s failure to thrive and wonders: “Is it because of its ideological incoherence? . . . the lack of true conversation between rabbis who lived inside of one intellectual realm and lay people who lived somewhere very different? Was it the mediocrity of the rabbis, who aspired to lead flocks that in large measure consisted of congregants who surpassed them in their intellectual sophistication [. . .]?”

These are important questions, especially since it seems almost impossible to find a third-generation Conservative Jew. Among my grandfather’s four surviving grandchildren, I am the only one with a kosher home and children who attended day school. As I look back on my formative years in the Conservative movement from my vantage point as a Torah-observant woman, I am astonished at the total lack of any meaningful discussion or teaching about God as our creator, the One who directs Jewish history. I am astonished at the shallowness of the education I received. When, in my early 20s, I attended my first Torah class taught by an Orthodox rabbi, I was shocked to discover that our matriarchs and patriarchs were real people who lived real lives that held lessons and inspiration for me, living thousands of years later.

If my experience is in any way typical, I would say that the Conservative movement failed because while it may have offered warmth and camaraderie, it offered almost no substance spiritually. In fact, the concepts of spiritual growth, God as our creator and guide of our destiny, and the depth and profundity of the Torah were nowhere to be found. Pulpit sermons were increasingly stoked with politically correct messages, bare of any spiritual substance. This may explain why the kids I grew up with in our synagogue are now either Orthodox or barely affiliated at all.

Judy Gruen

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Suggested Reading

Emancipation and Its Discontents

How a small, marginal community of Moravian Jews grappled with the challenges modernization and secularization brought to European Jewry.

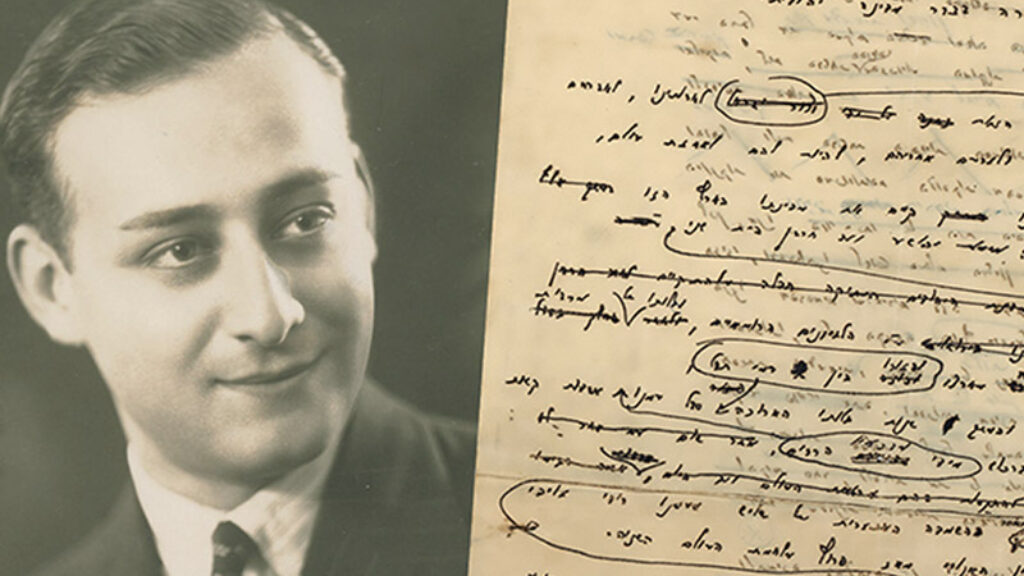

Israel’s Declaration of Independence: A Biography

Who wrote Israel's founding document and how does it express Israel’s values?

Is Beauty Power?

With charm, business savvy, and determination Kracow-born Rubinstein transformed herself from Chaja to Helena to “Madame.”

The Improbables

Not writing what you know can help an author steer away from autobiographical shoals, but it puts a certain research burden on the writer.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In