Hebraic America

On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress assigned Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson the task of designing the Great Seal for the United States of America. Adams turned to Greek mythology; Franklin and Jefferson turned to the Hebrew Bible. Franklin’s design had Moses “standing on the Shore, extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand. Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds, reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity.” Jefferson chose the children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. Franklin wanted the national motto to be “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.” While that motto was not ultimately chosen, Jefferson admired the phrase so much he decided to put it on his personal seal.

That the Exodus was the first choice of these two great figures of the American Enlightenment to symbolize the new nation testifies to the influence of Hebraic motifs in early America. But there is much more, as Eran Shalev shows in American Zion, and it is not just a matter of imagery. For some years, scholars involved in Hebraic political studies have sought to demonstrate the influence that biblical and even talmudic notions of limited government and separation of powers exerted on early modern Protestant political thought in Europe. Now Shalev is making similar claims about the influence of the Hebrew Bible in America.

To read Shalev’s book is to be transported to “a lost intellectual world” in which Americans saw themselves re-enacting the biblical drama of the ancient Israelites. The early Puritan “immigrants and succeeding generations interpreted the Great Migration of the 1630s as a crossing of the Red Sea and an escape from the British Egypt.” They were the new chosen people, elected by God for a divine mission in the wilderness of the new world. Shalev shows how Americans’ self-understanding as the elect living out God’s divine plan reverberated with these ideas long after the Puritans and the Revolution, sometimes in unexpected ways.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries a style of writing arose that Shalev calls pseudo-biblicism. In 1793, for instance, Richard Snowden wrote a two-volume history entitled The American Revolution: Written in the Style of Ancient History. Composed in an English archaic even for the late 18th century, it is littered with constructions such as “spake” and “thou.” America was called “the Land of Columbia” and the town of Concord “Concordia.” In other such newspaper articles and pamphlets, authors began sentences with the King James-esque “And it came to pass . . . ” and described the United States as stretching from “Dan even unto Beersheba.” Americans not only read the Hebrew Bible, some wrote American history in biblical style.

It is, of course, one thing to see the United States as re-enacting the Hebrew narrative of Exodus, chosenness, and covenant in a metaphorical sense. It is quite another to believe it as a matter of fact. Shalev shows how belief mingled with pseudo-science to produce the theory that the Indians were the biological descendants of the Hebrews. Not content with seeing themselves as the metaphorical descendants of the ancient Israelites, some 19th-century Americans were convinced that the “actual Israelites, or their biological descendants, [were] walking in their midst.” On this account the Amerindians were descendants of one of the Lost Ten Tribes, which were the progeny of the northern Israelite state that Assyria conquered and then dispersed in 722 B.C.E.

Though reviled by Jefferson and other sober thinkers, the Hebrew-Indian thesis proved remarkably resilient, surviving well into the 19th century. There is, of course, something bizarre about the idea, given that Americans were supposed to be the chosen people and the Indians those who stood in the way of advancing “civilization.” Nonetheless, the idea exerted a strange cultural fascination. Indeed, the most successful religious movement of the 19th century, Mormonism, incorporated elements of pseudo-biblicism and the Hebrew-Indian thesis. Shalev even suggests that “[t]he Book of Mormon should thus be seen in the context of contemporary texts written in biblical idiom which presented themselves as ancient, often Hebraic, in origin, mysteriously recovered, and translated from an exotic language for presentation before an American audience.” Placing Mormonism within the genus of Hebraic influence is thought-provoking, but one wonders whether an apple that has fallen so far from the tree is really of the same species.

In addition to envisioning themselves as re-enacting Hebraic narratives, Americans also looked to the Hebrew Bible for political teachings. Pastors such as Samuel Langdon, president of Harvard, and Ezra Stiles, president of Yale, gave sermons in which they culled political lessons from biblical stories. During the Revolution, the story of Gideon resonated strongly with the anti-monarchical rebels, who identified with the man of military prowess who saved the Israelites from their enemies on the battlefield, but refused to be their king. The colonists also enlisted the story of Esther and Haman to condemn the corruption of the British monarchy. Haman, the model of a corrupt advisor to a gullible monarch, “did not attempt to attack the polity from the outside with military power. Instead he manipulated and duped a monarch to subvert the empire from within.” Esther’s conduct taught that ambition corrupts and that power needs to be checked. That such references were readily understood is testament to the widespread biblical literacy of early America.

Apart from noting the frequent appropriation of biblical narratives, Shalev provides an account of the repeated efforts on the part of Americans, from the time of the Revolution onward, to “fully elaborate on the republican nature of the ancient Hebrew form of government and its correlations to its American counterpart.” In 1784, for instance, a Connecticut preacher named Joseph Huntington described the United States governed by the rather loose Articles of Confederation as living under “the best civil constitution now in the world, the same in the general nature of it, with that he gave to Israel in the days of Moses.” Sixty-nine years later, in his monumental Commentaries on the Laws of the Ancient Hebrews, Enoch Wines, a Congregationalist minister from New Jersey, drew a similar comparison between ancient Israel and America under the Constitution. The Israelite “states,” he wrote, possessed power that “was sovereign within the limits of their reserved rights. Still, there was both a real and a vigorous government.” Just as in the United States, “the Hebrew tribes were, in some respects, independent sovereignties, while, in other respects, their individual sovereignty was merged in the broader and higher sovereignty of the commonwealth of Israel.” In the eyes of Huntington and Wines, republicanism, separation of powers, and federalism were both American and Hebraic.

It is hard to pick the right word for the work the Hebrew Bible did in the United States. Is it influence or reflection, appropriation or inspiration? There is no doubt that the Bible was central to Puritan culture and that ideas of exodus and covenant and chosenness reverberated down through the American generations. But it is harder to assess the magnitude of that influence when one moves from the 17th to the 18th and 19th centuries. Perhaps we ought to distinguish between strong and weak versions of the thesis. In the strong version, the Hebrew Bible played a decisive role in shaping American culture and political thought. According to the weaker thesis, Hebraic narratives were used as metaphors and tropes to explain, and reconcile people to, what was in reality a new order for the ages.

One can argue both sides. But Shalev does little to address the preponderance of evidence that runs counter to the formative influence of Hebraic ideas. Most of the dramatis personae Shalev brings on stage did not play central roles in the American drama. It is hard to tell the story of American political culture without longer discussions than he provides of the great figures of the founding era, including, for instance, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, George Mason, and James Madison. These architects of the American Constitution—including Franklin and Jefferson, their ideas for the Great Seal notwithstanding—are almost completely absent from Shalev’s book.

The case of James Madison is particularly instructive. He stayed at Princeton in order to deepen his study of Hebrew, but in his pre-Convention personal writings the Hebrew Bible rarely surfaces. In his notes entitled “Of Ancient and Modern Confederacies,” written in 1787, for example, he looks to the confederacies of the Greeks, the Romans, the Dutch, the Belgians, and the Germans; he cites Montesquieu, Polybius in Latin, and the historian Malby. There is nothing about the Hebrew Republic or from the Hebrew Bible. With regard to the defining features of the American government—separation of powers, checks and balances, a singular elected executive, republican government with the majority of office holders elected by a (relatively) large suffrage, vesting the vast majority of powers in a bicameral legislature—it is hard to say that any of this is really taken from the Hebrew Bible.

There might be some affinities, a few points in the 17th century when a few wires were crossed here and there that produced an evanescent spark. But when one turns from Samuel Langdon to James Madison, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the political institutions of Jerusalem did not exert a decisive influence on the political institutions that came out of Philadelphia.

While the magnitude of the influence of the Hebrew Bible is hard to gauge, there is no doubt that it waxed from the Puritans to the Second Great Awakening and waned in the years leading up to the Civil War. Shalev attributes this to a change in American culture: Hebraic themes were better suited for institutional design and grand cultural and political narratives, while the New Testament was a better fit for the individualistic democracy of the mid-19th century, heavily populated by new adherents of evangelical creeds focused on their own personal salvation.

The Hebrew Bible also lost ground because it appeared to many Americans to sanction slavery. Pro-slavery apologists made use of it to show that slavery was permitted. They famously cited the curse that Noah laid on the progeny of Ham, whom they supposed to be the progenitor of black Africans. They noted that Mosaic Law permitted the enslavement of “heathens” and cited other passages from Genesis, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy to support slavery. While abolitionists retorted by distinguishing biblical servitude from the quite different race-based chattel slavery in the United States, they could not prevent the Hebrew Bible from being tarnished and eclipsed by the New Testament (despite its own failure to condemn slavery explicitly). During the Civil War itself, the Hebrew Bible enjoyed something of a resurgence, only to wane again afterward.

Surprisingly, Shalev presents no substantial analysis of the greatest political Hebraist of American history, Abraham Lincoln. It is hard to judge the true influence of Hebraic ideas in America without giving him his due. Indeed, Lincoln’s likeness is literally enshrined in his memorial between the Gettysburg Address and his second inaugural address, each containing Hebraic ideas.

On the whole, Shalev’s work provides little support for those who would like to believe that the way of life, moral lessons, and political institutions of the Hebrew Bible overlap with liberal, capitalistic, republican America. But American Zion will also be unwelcome to those who think that America is a secular country entirely built on secular ideals. There is no doubt that the Hebrew Bible was an important piece of the American cultural mosaic. But if it shaped American culture, Americans also shaped it to fit their particular needs: It supported the British monarchy in the French and Indian War, and it was then against the British tyranny and for republican liberty during the Revolution. It first supported the Articles and a loose confederation, but was then also the new national power under the Constitution. Americans employed it both for slavery and against it.

Perhaps the soundest American use of the Bible is to reinforce the idea that we Americans are not the chosen people, but, as Abraham Lincoln put it, the almost chosen people. He thought that the Bible’s moral vision stood above our best efforts, beckoning us to improve, to reach upwards toward our better selves. We are in an American covenant that we have yet to achieve and that we must continually strive to achieve. In wanting God to be behind us, we are liable to forget that He is above us. That was the view of America’s greatest biblical republican.

Suggested Reading

Those Days Are Gone Forever

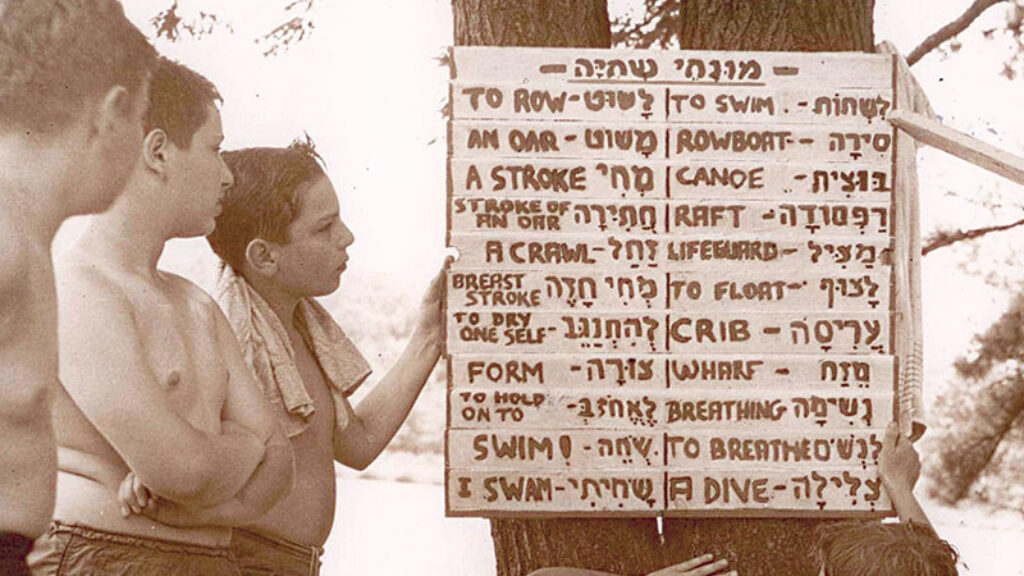

What, exactly, is camp spirit?

The Lost Textual Treasures of a Hasidic Community

The Regensburg Library at the University of Chicago contains a catalogue of markings and stamps from books saved from Nazi destruction. One such stamp comes from the library of the Karlin-Stolin Hasidim, a collection that might contain the most valuable manuscript for understanding the roots of Hasidism. But where is it?

Back in the USSR

On the ephemeral nature of home and “certificates of cowlessness” in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region.

The Hebrew Teacher

After his baptism, Judah Monis observed the Christian Sabbath on Saturdays, giving rise to suspicion, and for 38 years taught mandatory Hebrew to rebellious students.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In