Open-Door Policy

Last year, in a now-infamous commencement address to the graduates at the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College, novelist Michael Chabon surprised his audience with a disquisition on the virtues of intermarriage, which he described as the “source of all human greatness.” Expressing abhorrence of “homogeneity and insularity, exclusion and segregation,” he urged the graduates—newly credentialed rabbis and educators—to “find room in our Jewish community for all those who want to share in our traditions.”

In a scathing response, Sylvia Fishman, Steven Cohen, and Jack Wertheimer charged Chabon with seeking to “dismantle Judaism.” Their real quarry, however, was not the showboating novelist but rather the “left camp” in the broader Jewish communal debate over intermarriage. By failing to come to terms with the damage intermarriage has caused to Jewish family and communal life, Fishman, Cohen, and Wertheimer argued, advocates for greater outreach to intermarried families opened the door to Chabon’s more extreme rhetoric: “We urge the proponents of welcoming and inclusion . . . to think anew about where they stand in regard to Chabon’s challenge. . . . Where would you draw boundaries?”

Robert Mnookin, a Harvard Law professor and self-described secular Jew, picks up that gauntlet. His book, The Jewish American Paradox, advocates broadening the criteria for inclusion in the Jewish collective and opening wide the doors of Jewish communal life. The book expresses Mnookin’s conviction that only a Judaism of choice, open to all who publicly declare their belonging, has any prospect of flourishing in American society.

Mnookin began pondering the question of Jewish continuity when, as a grandparent, he asked himself how likely it was that his grandchildren would be Jewish. In contrast to people like Chabon, he discovered that he cared about the answer to that question a great deal. Against the “right camp” in the intermarriage debate, however, he believes that the effort to discourage intermarriage is simply a “fool’s errand,” which will not be made more successful by repetitive hand wringing. Moreover, “[f]ar from promoting the survival and distinctiveness of the Jewish people, it risks alienating many young Jews and, for those who intermarry, their children as well.”

The paradox at the center of the book is familiar to observers of American Jewish life: American Jews have achieved great integration into American society and, on the whole, have done quite well but now face the specter of their community’s assimilation. Beyond the precincts of Orthodoxy, Mnookin argues, Jewish life in America is threatened by secularization, intermarriage, and political divisions over Israel. Moreover, he doubts the threat of anti-Semitism will return American Jews to a more robust identity, as it did in other times and places. (Mnookin wrote this book before the Pittsburgh and Poway massacres, and I wonder whether his confidence in the diminished relevance of anti-Semitism has been at all shaken—mine certainly has been.)

Where should our communal borders be drawn to enable Jewish life to flourish? Mnookin surveys existing alternatives—the halakhic emphasis on matrilineal descent; racial definitions focused on “Jewish blood”; definitions centered on ethnicity, religious practice, and those of Israeli jurisprudence—and finds each to be either overinclusive or underinclusive. He objects, for example, to the halakhic notion that a person born or converted to Judaism cannot cease to be Jewish. Instead, Jews ought to be allowed to opt out of the collective—as, he notes, prominent public figures such as developmental psychologist Erik Erikson and former secretary of state Madeleine Albright did under very different circumstances.

More importantly, Mnookin argues that in an age of high rates of intermarriage and fluid group boundaries, people ought to be able to opt in more easily. As Jewish life is not limited to the religious domain, and most American Jews are fairly secular, admission to the collective should not be through religious conversion only. Instead, Mnookin proposes “public self-identification” as a criterion for belonging. It is a standard that is “broadly inclusive, emphasizes individual choice, and does not require people to express their Jewishness in any particular way.”

By encouraging a “big-tent” approach to communal boundaries, Mnookin hopes to engage an expanding circle of people, including the children of intermarriage, non-Jewish spouses of Jews, those with a single Jewish grandparent—or even more remote Jewish ancestry—as well as people who are Jewish by birth and ethnicity but identify with another religion. Recognizing that all Jews cannot agree to this approach, Mnookin acknowledges that individual congregations, schools, and other organizations will continue to enforce their own standards.

What I’m really arguing for is greater tolerance for ambiguity. The Jewish community has evolved for thousands of years and is still evolving. The American community is increasingly diverse. Conflicting standards already exist. The intermarriage rate is exploding. Instead of fighting this trend, which I think is futile, we should find a productive way to address it. . . .

What I’m trying to get at is a level of generosity. A recognition that there is no standard that neatly solves all problems. An acknowledgement that, as a practical matter, American Jews do have the gift of individual choice. Let’s reach out to those who might be reachable. Welcome everyone who wants to come in.

Mnookin recognizes that his call for a Judaism partially untethered from ethnicity and descent is historically unprecedented—that it “violates centuries of Jewish tradition.” Drawing on several studies that, as it happens, I coauthored with colleagues at Brandeis University, he nonetheless makes the case for the viability of an “opt-in” Judaism. He cites, for example, our finding, based on the Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey of Jewish Americans, that millennial generation children of intermarriage were more likely than the offspring of intermarriage in previous generations to have been raised Jewish, and to identify as Jewish in adulthood, even by the more restrictive category of “Jewish by religion.”

Mnookin does not seem overly concerned by the thin version of Judaism practiced by most of the children of intermarriage. His analysis is distinguished by a lack of nostalgia for an imagined golden age of American Judaism when levels of religious observance were supposedly higher. As an ambivalent secular Jew who raised his own children with little Jewish education, he grasps that assimilation does not only occur as a consequence of intermarriage. Moreover, witnessing both of his adult children, one of whom married a Jew and one a non-Jew, choose to raise Jewish children makes palpable for him the transformation of American Jewry into an increasingly voluntary collective—one that is attractive to a range of people who have disparate connections to the Jewish people.

It is a collective, however, whose more tentative members are sometimes discouraged by narrow, halakhic standards of belonging and party-line conformity in relation to Israel. In the future, Mnookin frets, “Those who don’t fit in—probably including my descendants—will be marginalized. Over time, those who feel alienated and excluded . . . will likely stop identifying themselves as Jewish at all.” This is really the crux of Mnookin’s argument. Like many parents and grandparents, he worries that children who lack proper Jewish bona fides will be rejected by communal authorities and will in turn abandon their tenuous but potentially developing Jewish identities.

Mnookin is hardly the first to advocate a big-tent approach. Decades ago, the Reconstructionist and Reform movements decided to recognize patrilineal descent as a legitimate basis for Jewish belonging. More recently, Reform Judaism—numerically, the largest denomination—declared “audacious hospitality” directed toward those remote from Jewish life to be a centerpiece of its mission. Although the Conservative movement recently reaffirmed its prohibition on rabbinic officiation at mixed marriages, it increasingly encourages strenuous efforts to welcome interfaith families into other aspects of communal life, including celebrations before and after the wedding ceremony, and inclusion of non-Jewish spouses as synagogue members. Even Chabad, despite its haredi origins, is, at least unofficially, welcoming of intermarried couples to some of its outreach programs. Kal ve-chomer, as the rabbis would say, the secular institutions of Jewish life, including federations, Jewish community centers, Hillels, and Birthright, all of whom unequivocally embrace intermarried families and their adult offspring. Mnookin is clearly pushing at an open door.

This big-tent approach, moreover, has not

gone unnoticed. Researcher Michelle Shain and I, together with several

colleagues, surveyed hundreds of Jewish-Jewish and Jewish–non-Jewish couples,

asking both partners questions about their religious attitudes, practices, and

experiences. We found, unsurprisingly, that mixed couples were substantially

less likely to observe Jewish holidays, consume Jewish culture, and express a

commitment to raising their children Jewish. Only a small minority of those

same couples, however, described feeling unwelcome in the Jewish community, and

virtually no couples who sought rabbinic officiation for their wedding ceremony

had difficulty finding it. Disinterest in religion in general—which is both a

cause and effect of intermarriage—is a better explanation for their

comparatively low levels of Jewish commitment. In short, there is little reason

to believe that community gatekeepers discourage intermarried couples or their

offspring from identifying as

Jewish when they choose to do so.

Whether the increasingly fluid and inclusive approach to Jewish belonging will enable liberal and secular Judaism to flourish in the United States beyond the next generation is really, I believe, an open question. Contributors to these pages have often expressed profound pessimism on this score. Although predicting Jewish population trends is demonstrably more difficult than many commentators would like to think, I believe there are grounds for a more optimistic view.

After rising sharply in the final decades of the 20th century, the intermarriage rate appears to have stabilized. Intermarriage, moreover, has the immediate effect of sharply increasing the number of households that include a Jewish adult, for the obvious reason that marriage between two Jews produces a single household, whereas marriages of two Jews to non-Jews produce two households. Therefore, the lower rates of participation of interfaith families may actually prove sustainable from a communal and demographic standpoint.

It is also critical to remember that very little about American Jewish life remains static for long. In recent decades, organized Jewry’s practices of welcoming and outreach have increased the proportion of children raised in mixed households that participate in Jewish educational experiences in childhood and during the college years, and that identify as Jewish in adulthood. As Mnookin reminds us, moreover, Jewish practices of individuals and families often wax and wane over their lifetime: “Even if the Jewish strand of their identity is very thin at this point in their lives, it may become more important at a later time, as it did for me.” This is an important point that is lost on many demographic pessimists. American Jewish life features considerable circulation between core and periphery, and, if trends regarding incorporation of the offspring of intermarriage continue, a substantial portion of that population may be retained in or returned to Jewish communal life.

Ultimately, the fate of American Judaism may depend less on the battle over boundaries—a battle that advocates of big-tent Judaism seem to have largely won outside the Orthodox community—than with the social forces Mnookin identifies as the main causes of assimilation. These forces—increasing secularism in the broader society, political divisions over Israel, and intermarriage—will shape the Jewish future in America far more than the policy pronouncements of communal gatekeepers. Many Jewish educators, innovators, and funders are working hard to shape these trends; only time will tell whether their efforts can revitalize and sustain non-Orthodox American Jewish life.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Two Poems

Two untitled poems by Avraham Halfi, translated by Leon Wieseltier.

Not of This World

In writing his first book for young readers, Aharon Appelfeld seems to have split himself and his life story between the two title characters: resourceful Adam, a boy of the land whose knowledge of the forest keeps them safe and fed, and bookish Thomas, a doubter in both faith and his own abilities.

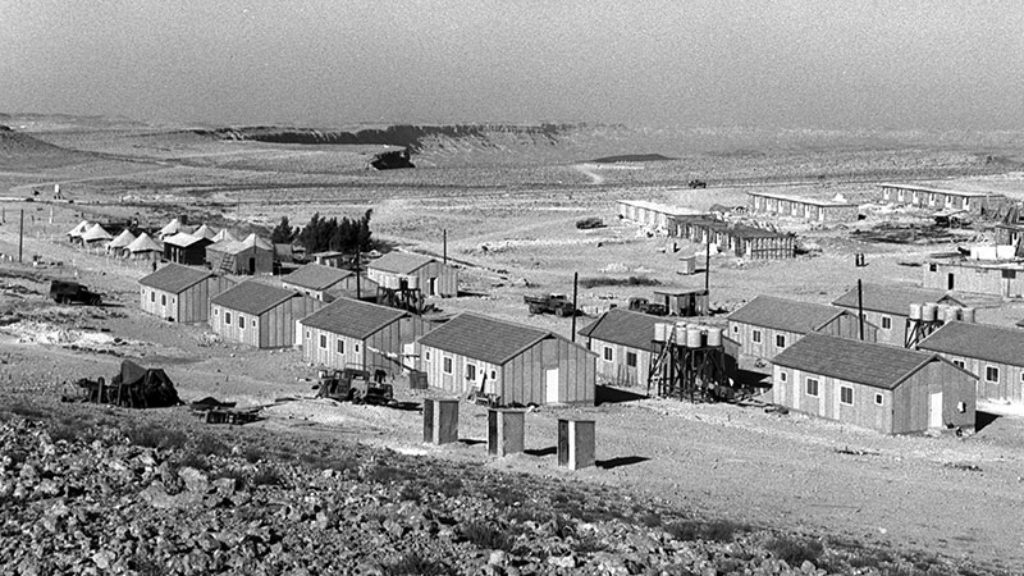

Seventy Years in the Desert

At the 1965 International Bible Contest, David Ben-Gurion posed some of the questions. He also asked two to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

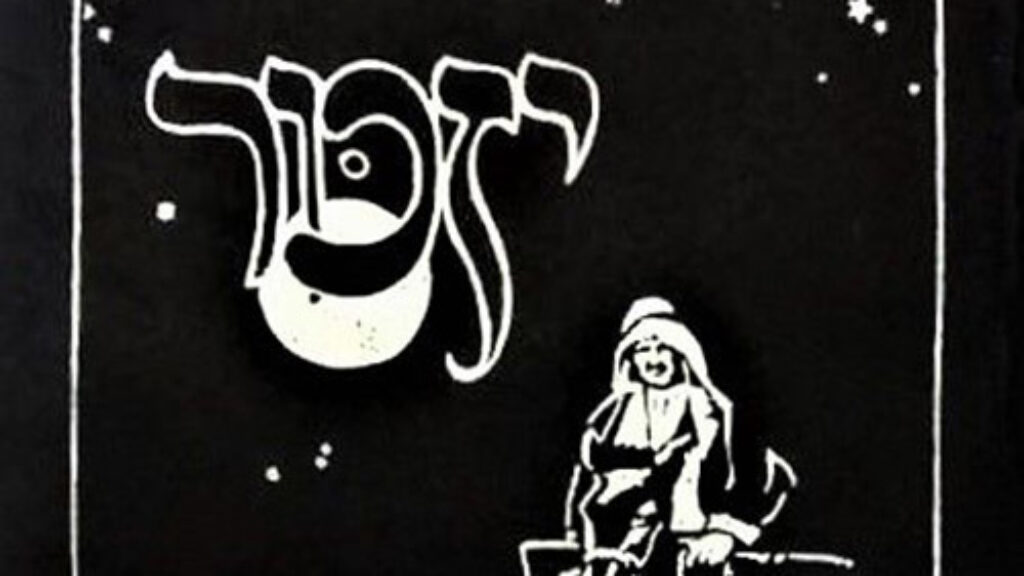

Let the People of Israel Remember

The earliest literary commemoration of Zionism’s fallen heroes was a book entitled Yizkor, published in Palestine in 1911 by members of Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion).

Concerned Jew

The problem is not so much a lack of acceptance as it is lack of connection. A lot of the the Jewish young people today have no connection at all to Judaism.

What we need is better Jewish education and more emphasis on Judaism in the home. If we do that there will be less intermarriage and more success when reaching out to the Jewish children of intermarriage.